Lèse-majesté: Difference between revisions

m Dating maintenance tags: {{Split section}} |

→Thailand: split content to Lèse majesté in Thailand |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

===Thailand=== |

===Thailand=== |

||

{{ |

{{main|Lèse majesté in Thailand}} |

||

[[Thailand]]'s [[Law of Thailand|Criminal Code]] has carried a prohibition against lese-majesty since 1908.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/6547413.stm NEWS.BBC.co.uk]</ref> In 1932, when Thailand's monarchy ceased to be absolute and a [[Constitution of Thailand|constitution]] was adopted, it too included language prohibiting lese-majesty. The [[2007 Constitution of Thailand]], and all seventeen versions since 1932, contain the clause, "The King shall be enthroned in a position of revered worship and shall not be violated. No person shall expose the King to any sort of accusation or action." Thai Criminal Code elaborates in Article 112: "Whoever defames, insults or threatens the King, Queen, the Heir-apparent or the Regent, shall be punished with imprisonment of three to fifteen years." Missing from the Code, however, is a definition of what actions constitute "defamation" or "insult".<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/7604935.stm NEWS.BBC.co.uk]</ref> From 1990 to 2005, the Thai court system only saw four or five lese-majesty cases a year. From January 2006 to May 2011, however, more than 400 cases came to trial, an estimated 1,500 percent increase.<ref name="increase">{{cite web |url=http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20110527/ap_on_re_as/as_thailand_monarchy |title=Thailand arrests American for alleged king insult |author=Todd Pitman and Sinfah Tunsarawuth |date=27 March 2011 |agency=Associated Press |accessdate=27 May 2011}}</ref> Observers attribute the increase to increased polarization following the [[2006 Thai coup d'état|2006 military coup]] and sensitivity over the elderly king's declining health.<ref name="increase"/> |

[[Thailand]]'s [[Law of Thailand|Criminal Code]] has carried a prohibition against lese-majesty since 1908.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/6547413.stm NEWS.BBC.co.uk]</ref> In 1932, when Thailand's monarchy ceased to be absolute and a [[Constitution of Thailand|constitution]] was adopted, it too included language prohibiting lese-majesty. The [[2007 Constitution of Thailand]], and all seventeen versions since 1932, contain the clause, "The King shall be enthroned in a position of revered worship and shall not be violated. No person shall expose the King to any sort of accusation or action." Thai Criminal Code elaborates in Article 112: "Whoever defames, insults or threatens the King, Queen, the Heir-apparent or the Regent, shall be punished with imprisonment of three to fifteen years." Missing from the Code, however, is a definition of what actions constitute "defamation" or "insult".<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/7604935.stm NEWS.BBC.co.uk]</ref> From 1990 to 2005, the Thai court system only saw four or five lese-majesty cases a year. From January 2006 to May 2011, however, more than 400 cases came to trial, an estimated 1,500 percent increase.<ref name="increase">{{cite web |url=http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20110527/ap_on_re_as/as_thailand_monarchy |title=Thailand arrests American for alleged king insult |author=Todd Pitman and Sinfah Tunsarawuth |date=27 March 2011 |agency=Associated Press |accessdate=27 May 2011}}</ref> Observers attribute the increase to increased polarization following the [[2006 Thai coup d'état|2006 military coup]] and sensitivity over the elderly king's declining health.<ref name="increase"/> |

||

Neither the King nor any member of the Royal Family has ever personally filed any charges under this law. In fact, during his birthday speech in 2005, King [[Bhumibol Adulyadej]] encouraged criticism: "Actually, I must also be criticized. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know." He later added, "But the King ''can'' do wrong," in reference to those he was appealing to not to overlook his human nature.<ref name="wrong">{{cite web |date=5 December 2005 |url=http://www.nationmultimedia.com/2005/12/05/headlines/data/headlines_19334288.html|title=Royal Birthday Address: 'King Can Do Wrong'|publisher=National Media|accessdate=26 September 2007}} |

Neither the King nor any member of the Royal Family has ever personally filed any charges under this law. In fact, during his birthday speech in 2005, King [[Bhumibol Adulyadej]] encouraged criticism: "Actually, I must also be criticized. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know." He later added, "But the King ''can'' do wrong," in reference to those he was appealing to not to overlook his human nature.<ref name="wrong">{{cite web |date=5 December 2005 |url=http://www.nationmultimedia.com/2005/12/05/headlines/data/headlines_19334288.html|title=Royal Birthday Address: 'King Can Do Wrong'|publisher=National Media|accessdate=26 September 2007}}</ref> |

||

Social activists such as [[Sulak Sivaraksa]] were charged with the crime in the 1980s and 1990s because they allegedly criticized the king; Sulak was eventually acquitted.<ref>[http://www.ipsnewsasia.net/en/node/142 "A Critic May Now Look at a King"], Macan-Markar, Marwaan, The Asian Eye, 18 May 2005</ref> |

|||

Frenchman Lech Tomasz Kisielewicz allegedly committed lese-majesty in 1995 by making a derogatory remark about a Thai princess while on board a [[Thai Airways International|Thai Airways]] flight. Although in international airspace at the time, he was taken into custody upon landing in [[Bangkok]] and charged with offending the monarchy. He was detained for two weeks, released on bail, and acquitted after writing a letter of apology to the king, and deported.{{Citation needed|date=August 2008}} In March 2007, Swiss national Oliver Jufer was convicted of lese-majesty and sentenced to 10 years in jail for spray-painting graffiti on several portraits of the king while drunk in [[Chiang Mai]];<ref>BBC News, [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/in_depth/6498297.stm Sensitive heads of state], 29 March 2007</ref> he was pardoned by the king on 12 April 2007 and deported.<ref>BBC News, [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/6547413.stm Thailand's king pardons Swiss man], 12 April 2007</ref> |

|||

In March 2008, Colonel Watanasak Mungkijakarndee of Bang Mod police station filed a case against Jakrapob Penkhair a politician and spokesman for former premier Thaksin Shinawatra, for public statements threatening violence and national security made on the [[Foreign Correspondents' Club#Thailand|Foreign Correspondents' Club of Thailand]] (FCCT) stage in August 2007.<ref>The Nation ([http://www.nationmultimedia.com/2008/05/29/politics/politics_30074295.php NationMultimedia.com]): Police to summon Jakrapob for allegedly lese majeste</ref> In 2008 [[BBC News|BBC]] South-East Asia correspondent and FCCT vice-president Jonathan Head was accused of lese-majesty three times by Col. Watanasak. Col. Watanasak filed new charges and evidence highlighting a conspiracy connecting Thaksin Shinawatra, Jakrapob Penkhair and Jonathan Head to [[Veera Musikapong]] at the FCCT. Jonathan Head was subsequently transferred by the BBC to Turkey.<ref>[http://www.manager.co.th/Crime/ViewNews.aspx?NewsID=9510000150800 Colonel Watanasak filed further charges against BBC reporter at CSD], [[Manager Online]], 23 December 2008</ref> Prime Minister Abhisit Vejajiva has still not made a decision as to whether prosecutors should continue proceedings against Jakrapob Penkhair. |

|||

In September 2008, [[Harry Nicolaides]]<ref>[http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2008/09/03/2354659.htm Australian man refused bail for insulting Thai King], [[ABC Online]], 3 September 2008</ref> from Melbourne, Australia, was arrested at Bangkok's international airport<ref>[http://www.reuters.com/article/artsNews/idUSBKK9474820080903 Australian arrested in Thailand for lese-majeste]</ref> and charged with lese-majesty, for an offending passage in his self published book ''Verisimilitude''. After pleading guilty, he was sentenced to three years in jail<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/7836854.stm NEWS.BBC.co.uk], Writer jailed for Thai 'insult'</ref> but then pardoned by the king, released, and deported.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/7903019.stm NEWS.BBC.co.uk], Thailand frees Australian writer</ref> |

|||

On 29 April 2010, Thai businessman [[Wipas Raksakulthai]] was arrested following a post to his Facebook account allegedly insulting Bhumibol.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5gl4ZSdUYK_wsrAZM2XQpzlrMtfGA |title=Thai man arrested for Facebook post about monarchy |date=30 April 2010 |agency=Agence France-Presse |accessdate=15 May 2011}}</ref> |

|||

The arrest was reportedly the first lese-majesty charge against a Thai Facebook user.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.bangkokpost.com/tech/mobile/184681/govt-cracks-down-on-social-networking-forums |title=Govt cracks down on social networking forums|date=3 July 2010 |work=Bangkok Post |accessdate=15 May 2011}}</ref> In response, [[Amnesty International]] named Wipas Thailand's first [[prisoner of conscience]] in nearly three decades.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nationmultimedia.com/home/Amnesty-International-names-Thailands-first-prison-30155366.html |title=Amnesty International names Thailand's first 'prisoner of conscience' |author= Pravit Rojanaphruk |date=14 May 2011 |work=The Nation |accessdate=15 May 2011}}</ref> |

|||

On 27 May 2011, an American citizen, Joe Gordon (Lerpong Wichaikhammat), was arrested on charges he insulted the country's monarchy, in part by posting a link on his blog to a banned book about the ailing king. Gordon had lived in the United States for thirty years before returning to Thailand. He is also reportedly suspected of translating, from English into Thai, portions of ''[[The King Never Smiles]]'' – an unauthorized biography of King [[Bhumibol Adulyadej]] – and posting them online along with articles he wrote that allegedly defame the royal family.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/05/27/colorado-man-arrested-in-thailand_n_867982.html |title=Joe Gordon, Colorado Man Living In Thailand, Arrested For Allegedly Insulting Monarchy |work=Huffington Post |date=27 May 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url= http://freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=581&alert=68 |

|||

|title= Freedom Alert: American arrested in Thailand, accused of criticizing monarchy | publisher=[[Freedom House]]}}</ref> After being denied bail eight times, a shackled–and–handcuffed Gordon said in court on 10 October, “I’m not fighting in the case. I’m pleading guilty, sirs.”<ref>{{cite news |

|||

|title=Joe Gordon pleads guilty to lese majeste charges |url= |agency= AP|newspaper= [[Asian Correspondent]] |

|||

|date= 10 October 2011 |

|||

|accessdate=10 October 2011 |

|||

| quote = BANGKOK (AP) – Hoping for a lenient sentence, a shackled U.S. citizen pleaded guilty Monday to charges of defaming Thailand’s royal family, a grave crime in this Southeast Asian kingdom that is punishable by up to 15 years in jail. |

|||

}}</ref> On 8 December 2011] a court in Thailand sentenced Joe Gordon to two and a half years in prison for defaming the country's royal family by translating excerpts of a locally banned biography of the king and posting them online. [www.cbsnews.com/8301-202_162-57339098/thailand-jails-u.s-man-for-insulting-king/] |

|||

In September 2011, computer programmer Surapak Puchaieseng was arrested, detained and had his computer confiscated after accused of insulting the Thai royal family on Facebook – his arrest marked the first lèse majesté case since prime minister [[Yingluck Shinawatra]] was elected.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=581&alert=119|title= Thai Computer Programmer Detained After Criticizing Monarchy on Facebook| publisher=[[Freedom House]]}}</ref> The 10 October AP report on Joe Gordon's plea adds that "Yingluck’s government has been just as aggressive in pursing the cases as its predecessors." |

|||

===Others=== |

===Others=== |

||

Revision as of 21:06, 8 April 2012

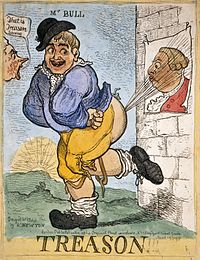

Lese-majesty /ˌliːz ˈmædʒ[invalid input: 'i-']sti/[1] (French: lèse majesté [lɛz maʒɛste]; Law French, from the Latin laesa maiestas, "injured majesty"; in English, also lese majesty or leze majesty) is the crime of violating majesty, an offence against the dignity of a reigning sovereign or against a state.

This behavior was first classified as a criminal offence against the dignity of the Roman republic in Ancient Rome. In the Dominate, or Late Empire period the Emperors scrapped the Republican trappings of their predecessors and began to identify the state with their person.[2] Though legally the princeps civitatis (his official title, roughly 'first citizen') could never become a sovereign, as the republic was never officially abolished, emperors were deified as divus, first posthumously but by the Dominate period while reigning. Deified Emperors thus enjoyed the legal protection provided for the divinities of the state cult; by the time it was exchanged for Christianity, the monarchical tradition in all but name was well established.

Narrower conceptions of offences against Majesty as offences against the crown predominated in the European kingdoms that emerged in the early medieval period. In feudal Europe, various real crimes were classified as lese-majesty even though not intentionally directed against the crown, such as counterfeiting because coins bear the monarch's effigy and/or coat of arms.

However, since the disappearance of absolute monarchy, this is viewed as less of a crime, although similar, more malicious acts could be considered treason. By analogy, as modern times saw republics emerging as great powers, a similar crime may be constituted, though not under this name, by any offence against the highest representatives of any state. In particular, similar acts against heads of modern age totalitarian dictatorships are very likely to result in prosecution.

Current lese-majesty laws

Europe

In Germany, Switzerland,[3] and Poland it is illegal to insult foreign heads of state publicly.

- On 5 January 2005, Marxist tabloid publisher Jerzy Urban was sentenced by a Polish court to a fine of 20,000 złoty (about €5000 or US$6,200) for having insulted Pope John Paul II, a visiting head of state.[4]

- On 26–27 January 2005, 28 human rights activists were temporarily detained by the Polish authorities for allegedly insulting Vladimir Putin, a visiting head of state. The activists were released after about 30 hours and only one was actually charged with insulting a foreign head of state.[5]

- In October 2006, a Polish man was arrested in Warsaw after expressing his dissatisfaction with the leadership of Lech and Jarosław Kaczyński by passing gas loudly.[6]

Denmark

In Denmark, the monarch is protected by the usual libel paragraph (§ 267 of the penal code which allows for up to four months of imprisonment), but §115[7] allows for doubling of the usual punishment when the regent is target of the libel. When a queen consort, queen dowager or the crown prince is the target, the punishment may be increased by 50%. There are no historical records of §115 having ever been used, but in March 2011, Greenpeace activists who unfurled a banner at a dinner at the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference were charged under this section.[8] They received minor sentences for other crimes, but were acquitted of the charge relating to the monarch.[9]

Netherlands

In October 2007, a 47-year-old man was fined €400 for, amongst other things, lese-majesty in the Netherlands when he called Queen Beatrix a "whore" and described several sexual acts he would like to perform on her to a police officer.[10]

Spain

The Spanish satirical magazine El Jueves was fined for violation of Spain's lese-majesty laws after publishing an issue with a caricature of the Prince of Asturias and his wife engaging in sexual intercourse on the cover in 2007.[11]

Morocco

Moroccans are routinely prosecuted for statements deemed offensive to the King. The penal code states that the minimum sentence for a statement made in private (i.e.: not broadcast) is imprisonment for 1 year. For a public offense to the King, the minimum sentence is 3 years. In both cases, the maximum is 5 years.[12]

The case of Yassine Belassal[13] The Fouad Mourtada Affair, and Nasser Ahmed (a 95 year-old who died in jail after being convicted of lese-majesty), revived the debate on these laws and their applications. In 2008, an 18 year-old was charged with "breach of due respect to the king" for writing "God, Country, Barca" on a school board, in reference to his favorite football club. The national motto of Morocco is "God, Country, King".

In February 2012, 18 years old Walid Bahomane was convicted for posting two mild cartoons of the king on Facebook. The procès-verbal cites two facebook pages [sic] and an IBM computer being seized as evidence. Walid is officially prosecuted for "touching the sacralities".[14]

Thailand

Thailand's Criminal Code has carried a prohibition against lese-majesty since 1908.[15] In 1932, when Thailand's monarchy ceased to be absolute and a constitution was adopted, it too included language prohibiting lese-majesty. The 2007 Constitution of Thailand, and all seventeen versions since 1932, contain the clause, "The King shall be enthroned in a position of revered worship and shall not be violated. No person shall expose the King to any sort of accusation or action." Thai Criminal Code elaborates in Article 112: "Whoever defames, insults or threatens the King, Queen, the Heir-apparent or the Regent, shall be punished with imprisonment of three to fifteen years." Missing from the Code, however, is a definition of what actions constitute "defamation" or "insult".[16] From 1990 to 2005, the Thai court system only saw four or five lese-majesty cases a year. From January 2006 to May 2011, however, more than 400 cases came to trial, an estimated 1,500 percent increase.[17] Observers attribute the increase to increased polarization following the 2006 military coup and sensitivity over the elderly king's declining health.[17]

Neither the King nor any member of the Royal Family has ever personally filed any charges under this law. In fact, during his birthday speech in 2005, King Bhumibol Adulyadej encouraged criticism: "Actually, I must also be criticized. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know." He later added, "But the King can do wrong," in reference to those he was appealing to not to overlook his human nature.[18]

Others

In January, 2009 there was a diplomatic incident between Australia and Kuwait over an Australian woman being held for allegedly insulting the Emir of Kuwait during a fracas with Kuwaiti Immigration authorities.[19]

Even though the Supreme Leader of Iran is not a king, there are laws against insulting the station of the Supreme Leader.

Former laws

United Kingdom

In Scotland, section 51 of the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010 abolished the common law criminal offences of sedition and 'leasing-making'. The latter offence, also known as 'lease /ˈliːz/ making', was considered an offence of lese-majesty or making remarks critical of the Monarch of the United Kingdom. It had not been prosecuted since 1715.[20]

See also

References

- ^ "lese-majesty". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ TheFreeDictionary.com, "Lese majesty" TheFreeDictionary.com, Columbia Encyclopedia, retrieved 22 September 2006

- ^ Swiss Penal Code , SR/RS 311.0 (E·D·F·I), art. 296 (E·D·F·I)

- ^ IFEX.org, "Criminal Defamation Laws Hamper Free Expression" IFEX.org, retrieved 22 September 2006

- ^ NEWS.BBC.co.uk, "Sensitive heads of state", retrieved 30 January 2008

- ^ Ananova.com, "Police hunt farting dissident" ananova.com, retrieved 31 August 2008

- ^ Resinformation.dk

- ^ "COP-15 activists in lèse majesté case". Politiken. Copenhagen. 1 March 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ Københavns Byret (22-08-2011). Greenpeace-aktivister idømt betinget fængsel i 14 dage. (in Danish).

- ^ nrc.nl – Binnenland – Boete voor majesteitsschennis

- ^ "Spain royal sex cartoonists fined". BBC. 13 November 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ PCB.UB.es

- ^ BarcelonaReporter.com,

- ^ "Busted for Posting Caricatures of the King on Facebook". 8 February 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ NEWS.BBC.co.uk

- ^ NEWS.BBC.co.uk

- ^ a b Todd Pitman and Sinfah Tunsarawuth (27 March 2011). "Thailand arrests American for alleged king insult". Associated Press. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ "Royal Birthday Address: 'King Can Do Wrong'". National Media. 5 December 2005. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

- ^ SMH.com.au

- ^ "Justice Committee Official Report (see column 2942)". Scottish Parliament. 20 April 2010. Retrieved Feb 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)