Plasmid: Difference between revisions

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

*[http://www.ispb.org/ International Society for Plasmid Biology and other Mobile Genetic Elements] |

*[http://www.ispb.org/ International Society for Plasmid Biology and other Mobile Genetic Elements] |

||

*[http://histmicro.yale.edu/mainfram.htm History of Plasmids with timeline] |

*[http://histmicro.yale.edu/mainfram.htm History of Plasmids with timeline] |

||

*[http://www.edupdf.org/4256/bacterial-transformation-and-plasmid-recovery/ Bacterial Transformation and Plasmid Recovery] |

|||

Revision as of 18:19, 31 January 2014

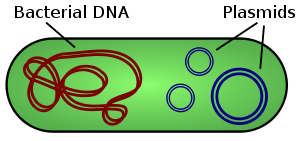

A plasmid is a small DNA molecule that is physically separate from, and can replicate independently of, chromosomal DNA within a cell. Most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria, plasmids are sometimes present in archaea and eukaryotic organisms. In nature, plasmids carry genes that may benefit survival of the organism (e.g. antibiotic resistance), and can frequently be transmitted from one bacterium to another (even of another species) via horizontal gene transfer. Artificial plasmids are widely used as vectors in molecular cloning, serving to drive the replication of recombinant DNA sequences within host organisms.[1]

Plasmid sizes vary from 1 to over 1,000 kbp.[1] The number of identical plasmids in a single cell can range anywhere from one to thousands under some circumstances. Plasmids can be considered part of the mobilome because they are often associated with conjugation, a mechanism of horizontal gene transfer.

The term plasmid was first introduced by the American molecular biologist Joshua Lederberg in 1952.[2]

Plasmids are considered replicons, capable of replicating autonomously within a suitable host. Plasmids can be found in all three major domains: Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya.[3] Similar to viruses, plasmids are not considered by some to be a form of life.[4] Unlike viruses, plasmids are naked DNA and do not encode genes necessary to encase the genetic material for transfer to a new host, though some classes of plasmids encode the sex pilus necessary for their own transfer. Plasmid host-to-host transfer requires direct mechanical transfer by conjugation, or changes in incipient host gene expression allowing the intentional uptake of the genetic element by transformation. Microbial transformation with plasmid DNA is neither parasitic nor symbiotic in nature, because each implies the presence of an independent species living in a detrimental or commensal state with the host organism. Rather, plasmids provide a mechanism for horizontal gene transfer within a population of microbes and typically provide a selective advantage under a given environmental state. Plasmids may carry genes that provide resistance to naturally occurring antibiotics in a competitive environmental niche, or the proteins produced may act as toxins under similar circumstances. Plasmids can also provide bacteria with the ability to fix nitrogen or to degrade recalcitrant organic compounds that provide an advantage when nutrients are scarce.[3]

Vectors

Plasmids used in genetic engineering are called vectors. Plasmids serve as important tools in genetics and biotechnology labs, where they're commonly used to multiply (make many copies of) or express particular genes.[5] Many plasmids are commercially available for such uses. The gene to be replicated is inserted into copies of a plasmid containing genes that make cells resistant to particular antibiotics and a multiple cloning site (MCS, or polylinker), which is a short region containing several commonly used restriction sites allowing the easy insertion of DNA fragments at this location. Next, the plasmids are inserted into bacteria by a process called transformation. Then, the bacteria are exposed to the particular antibiotics. Only bacteria that take up copies of the plasmid survive, since the plasmid makes them resistant. In particular, the protecting genes are expressed (used to make a protein) and the expressed protein breaks down the antibiotics. In this way, the antibiotics act as a filter to select only the modified bacteria. Now these bacteria can be grown in large amounts, harvested, and lysed (often using the alkaline lysis method) to isolate the plasmid of interest.

Another major use of plasmids is to make large amounts of proteins. In this case, researchers grow bacteria containing a plasmid harboring the gene of interest. Just as the bacterium produces proteins to confer its antibiotic resistance, it can also be induced to produce large amounts of proteins from the inserted gene. This is a cheap and easy way of mass-producing a gene or the protein it then codes for, for example, insulin or even antibiotics.

A plasmid can contain inserts of up to 30-40 kbp. To clone longer lengths of DNA, lambda phage with lysogeny genes deleted, cosmids, bacterial artificial chromosomes, or yeast artificial chromosomes are used.

Applications

Disease models

Plasmids were historically used to genetically engineer the embryonic stem cells of rats in order to create rat genetic disease models. The limited efficiency of plasmid-based techniques precluded their use in the creation of more accurate human cell models. However, developments in Adeno-associated virus recombination techniques, and Zinc finger nucleases, have enabled the creation of a new generation of isogenic human disease models.

Gene therapy

Some strategies of gene therapy require the insertion of therapeutic genes at pre-selected chromosomal target sites within the human genome. Plasmid vectors are one of many approaches that could be used for this purpose. Zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) offer a way to cause a site-specific double-strand break to the DNA genome and cause homologous recombination. Plasmids encoding ZFN could help deliver a therapeutic gene to a specific site so that cell damage, cancer-causing mutations, or an immune response is avoided.[6]

Episomes

In general, in eukaryotes, episomes are closed circular DNA molecules that are replicated in the nucleus. Viruses are the most common examples of this, such as herpesviruses, adenoviruses, and polyomaviruses. Other examples include aberrant chromosomal fragments, such as double minute chromosomes, that can arise during artificial gene amplifications or in pathologic processes (e.g., cancer cell transformation). Episomes in eukaryotes behave similarly to plasmids in prokaryotes in that the DNA is stably maintained and replicated with the host cell. Cytoplasmic viral episomes (as in poxvirus infections) can also occur. Some episomes, such as herpesviruses, replicate in a rolling circle mechanism, similar to bacterial phage viruses. Others replicate through a bidirectional replication mechanism (Theta type plasmids). In either case, episomes remain physically separate from host cell chromosomes. Several cancer viruses, including Epstein-Barr virus and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, are maintained as latent, chromosomally distinct episomes in cancer cells, where the viruses express oncogenes that promote cancer cell proliferation. In cancers, these episomes passively replicate together with host chromosomes when the cell divides. When these viral episomes initiate lytic replication to generate multiple virus particles, they in general activate cellular innate immunity defense mechanisms that kill the host cell.

Types

One way of grouping plasmids is by their ability to transfer to other bacteria. Conjugative plasmids contain tra genes, which perform the complex process of conjugation, the transfer of plasmids to another bacterium (Fig. 4). Non-conjugative plasmids are incapable of initiating conjugation, hence they can be transferred only with the assistance of conjugative plasmids. An intermediate class of plasmids are mobilizable, and carry only a subset of the genes required for transfer. They can parasitize a conjugative plasmid, transferring at high frequency only in its presence. Plasmids are now being used to manipulate DNA and may possibly be a tool for curing many diseases.

It is possible for plasmids of different types to coexist in a single cell. Several different plasmids have been found in E. coli. However, related plasmids are often incompatible, in the sense that only one of them survives in the cell line, due to the regulation of vital plasmid functions. Thus, plasmids can be assigned into incompatibility groups.

Another way to classify plasmids is by function. There are five main classes:

- Fertility F-plasmids, which contain tra genes. They are capable of conjugation and result in the expression of sex pilli.

- Resistance (R)plasmids, which contain genes that provide resistance against antibiotics or poisons. Historically known as R-factors, before the nature of plasmids was understood.

- Col plasmids, which contain genes that code for bacteriocins, proteins that can kill other bacteria.

- Degradative plasmids, which enable the digestion of unusual substances, e.g. toluene and salicylic acid.

- Virulence plasmids, which turn the bacterium into a pathogen.

Plasmids can belong to more than one of these functional groups.

Plasmids that exist only as one or a few copies in each bacterium are, upon cell division, in danger of being lost in one of the segregating bacteria. Such single-copy plasmids have systems that attempt to actively distribute a copy to both daughter cells. These systems, which include the parABS system and parMRC system, are often referred to as the partition system or partition function of a plasmid.

Plasmid maintenance

Some plasmids or microbial hosts include an addiction system or postsegregational killing system (PSK), such as the hok/sok (host killing/suppressor of killing) system of plasmid R1 in Escherichia coli.[7] This variant produces both a long-lived poison and a short-lived antidote. Several types of plasmid addiction systems (toxin/ antitoxin, metabolism-based, ORT systems) were described in the literature[8] and used in biotechnical (fermentation) or biomedical (vaccine therapy) applications. Daughter cells that retain a copy of the plasmid survive, while a daughter cell that fails to inherit the plasmid dies or suffers a reduced growth-rate because of the lingering poison from the parent cell. Finally, the overall productivity could be enhanced.

In contrast, virtually all biotechnologically used plasmids (such as pUC18, pBR322 and derived vectors) do not contain toxin-antitoxin addiction systems and thus need to be kept under antibiotic pressure to avoid plasmid loss.

Yeast plasmids

Yeast are organisms that naturally harbour plasmids. Notable plasmids are 2 µm plasmid - small circular plasmid often used for genetic engineering of yeast and linear pGKL plasmids from kluyveromyces lactis that are responsible for killer phenotype.[9]

Other types of plasmids are often related to yeast cloning vectors that include:

- Yeast integrative plasmid (YIp), yeast vectors that rely on integration into the host chromosome for survival and replication, and are usually used when studying the functionality of a solo gene or when the gene is toxic. Also connected with the gene URA3, that codes an enzyme related to the biosynthesis of pyrimidine nucleotides (T, C);

- Yeast Replicative Plasmid (YRp), which transport a sequence of chromosomal DNA that includes an origin of replication. These plasmids are less stable, as they can get lost during the budding.

Plasmid DNA extraction

As alluded to above, plasmids are often used to purify a specific sequence, since they can easily be purified away from the rest of the genome. For their use as vectors, and for molecular cloning, plasmids often need to be isolated.

There are several methods to isolate plasmid DNA from bacteria, the archetypes of which are the miniprep and the maxiprep/bulkprep.[5] The former can be used to quickly find out whether the plasmid is correct in any of several bacterial clones. The yield is a small amount of impure plasmid DNA, which is sufficient for analysis by restriction digest and for some cloning techniques.

In the latter, much larger volumes of bacterial suspension are grown from which a maxi-prep can be performed. In essence, this is a scaled-up miniprep followed by additional purification. This results in relatively large amounts (several micrograms) of very pure plasmid DNA.

In recent times, many commercial kits have been created to perform plasmid extraction at various scales, purity, and levels of automation. Commercial services can prepare plasmid DNA at quoted prices below $300/mg in milligram quantities and $15/mg in gram quantities (early 2007[update]).

Conformations

Plasmid DNA may appear in one of five conformations, which (for a given size) run at different speeds in a gel during electrophoresis. The conformations are listed below in order of electrophoretic mobility (speed for a given applied voltage) from slowest to fastest:

- Nicked open-circular DNA has one strand cut.

- Relaxed circular DNA is fully intact with both strands uncut, but has been enzymatically relaxed (supercoils removed). This can be modeled by letting a twisted extension cord unwind and relax and then plugging it into itself.

- Linear DNA has free ends, either because both strands have been cut or because the DNA was linear in vivo. This can be modeled with an electrical extension cord that is not plugged into itself.

- Supercoiled (or covalently closed-circular) DNA is fully intact with both strands uncut, and with an integral twist, resulting in a compact form. This can be modeled by twisting an extension cord and then plugging it into itself.

- Supercoiled denatured DNA is like supercoiled DNA, but has unpaired regions that make it slightly less compact; this can result from excessive alkalinity during plasmid preparation.

The rate of migration for small linear fragments is directly proportional to the voltage applied at low voltages. At higher voltages, larger fragments migrate at continuously increasing yet different rates. Thus, the resolution of a gel decreases with increased voltage.

At a specified, low voltage, the migration rate of small linear DNA fragments is a function of their length. Large linear fragments (over 20 kb or so) migrate at a certain fixed rate regardless of length. This is because the molecules 'resperate', with the bulk of the molecule following the leading end through the gel matrix. Restriction digests are frequently used to analyse purified plasmids. These enzymes specifically break the DNA at certain short sequences. The resulting linear fragments form 'bands' after gel electrophoresis. It is possible to purify certain fragments by cutting the bands out of the gel and dissolving the gel to release the DNA fragments.

Because of its tight conformation, supercoiled DNA migrates faster through a gel than linear or open-circular DNA.

Simulation of plasmids

The use of plasmids as a technique in molecular biology is supported by bioinformatics software. These programs record the DNA sequence of plasmid vectors, help to predict cut sites of restriction enzymes, and to plan manipulations. Examples of software packages that handle plasmid maps are LabGenius,[10] pDraw32, Geneious, Lasergene, GeneConstructionKit, ApE, Clone Manager, VectorFriends, and Vector NTI. These software help conduct entire experiments in silico before doing wet experiments [1].

See also

- Bacterial artificial chromosome

- Bacteriophage

- Circular DNA

- Provirus

- Segrosome

- Transposon

- Triparental mating

- Plasmidome

References

- ^ a b "What are Plasmids?" (Press release). http://www.innovateus.net/. 2006–2011. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

{{cite press release}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Lederberg J (1952). "Cell genetics and hereditary symbiosis". Physiol. Rev. 32 (4): 403–430. PMID 13003535.

- ^ a b Lipps G (editor). (2008). Plasmids: Current Research and Future Trends. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-35-6.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Sinkovics, J (1998). "The Origin and evolution of viruses (a review)". Acta microbiologica et immunologica Hungarica. 45 (3–4). St. Joseph's Hospital, Department of Medicine, University of South Florida College of Medicine, Tampa, FL, USA.: Akademiai Kiado: 349–90. ISSN 1217-8950. PMID 9873943.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Russell, David W.; Sambrook, Joseph (2001). Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kandavelou K; Chandrasegaran S (2008). "Plasmids for Gene Therapy". Plasmids: Current Research and Future Trends. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-35-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gerdes K, Rasmussen PB, Molin S (1986). "Unique type of plasmid maintenance function: postsegregational killing of plasmid-free cells". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83 (10): 3116–20. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.10.3116. PMC 323463. PMID 3517851.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kroll J, Klinter S, Schneider C, Voß I, Steinbüchel A (2010). "Plasmid addiction systems: perspectives and applications in biotechnology". Microb Biotechnol. 3 (6): 634–657. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00170.x. PMID 21255361.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gunge, N (July 1982). "Transformation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with linear DNA killer plasmids from Kluyveromyces lactis". Journal of bacteriology. 151 (1): 462–4. PMC 220260. PMID 7045080.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cormier, Catherine. "PSI: Biology in the Spotlight". Retrieved 5 November 2012.

Further reading

- Klein, Donald W.; Prescott, Lansing M.; Harley, John (1999). Microbiology. Boston: WCB/McGraw-Hill.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Smith, Christopher U. M. Elements of Molecular Neurobiology. Wiley. pp. 101, 111.

- Albert G. Moat, John W. Foster, Michael P. Spector (2002). Microbial Physiology. Wiley-Liss. ISBN 0-471-39483-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Episomes

- Piechaczek C, Fetzer C, Baiker A, Bode J, Lipps HJ (1999). "A vector based on the SV40 origin of replication and chromosomal S/MARs replicates episomally in CHO cells". Nucleic Acids Res. 27 (2): 426–428. doi:10.1093/nar/27.2.426. PMC 148196. PMID 9862961.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bode J , Fetzer CP, Nehlsen K, Scinteie M, Hinrichsen B-H, Baiker A, Piechazcek C, Benham C, Lipps HJ (2001). "The Hitchhiking principle: Optimizing episomal vectors for the use in gene therapy and biotechnology" (PDF). Gene Ther Mol Biol. 6: 33–46.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nehlsen K, Broll S, Bode J (2006). "Replicating minicircles: Generation of nonviral episomes for the efficient modification of dividing cells" (PDF). Gene Ther Mol Biol. 10: 233–244.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ehrhardt A, Haase R, Schepers A, Deutsch MJ, Lipps HJ, Baiker A. (2008). "Episomal vectors for gene therapy". Curr Gene Therapy. 8 (3): 147–161. doi:10.2174/156652308784746440. PMID 18537590.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Argyros O, Wong SP, Niceta M, Waddington SN, Howe SJ, Coutelle C, Miller AD, Harbottle RP (2008). "Persistent episomal transgene expression in liver following delivery of a scaffold/matrix attachment region containing non-viral vector". Gene Therapy. 15 (24): 1593–1605. doi:10.1038/gt.2008.113. PMID 18633447.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wong SP, Argyros O, Coutelle C, Harbottle RP (2009). "Strategies for the episomal modification of cells". Current Opinion in Molecular Therapeutics. 11 (4): 433–441. PMID 19649988.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Haase R, Argyros O, Wong SP, Harbottle RP, Lipps HJ, Ogris M, Magnusson T, Vizoso Pinto MG, Haas J, Baiker A. (2010). "pEPito: a significantly improved non-viral episomal expression vector for mammalian cells" (PDF). BMC Biotechnol. 10: 433–441. doi:10.1186/1472-6750-10-20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)