Trémaux tree: Difference between revisions

→In finite graphs: subsections; MSO |

|||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

==In finite graphs== |

==In finite graphs== |

||

===Existence=== |

|||

Every finite [[connected graph|connected]] [[undirected graph]] has at least one Trémaux tree. One can construct such a tree by performing a [[depth-first search]] and connecting each vertex (other than the starting vertex of the search) to the earlier vertex from which it was discovered. The tree constructed in this way is known as a depth-first search tree. If ''uv'' is an arbitrary edge in the graph, and ''u'' is the earlier of the two vertices to be reached by the search, then ''v'' must belong to the subtree descending from ''u'' in the depth-first search tree, because the search will necessarily discover ''v'' while it is exploring this subtree, either from one of the other vertices in the subtree or, failing that, from ''u'' directly. Every finite Trémaux tree can be generated as a depth-first search tree: If ''T'' is a Trémaux tree of a finite graph, and a depth-first search explores the children in ''T'' of each vertex prior to exploring any other vertices, it will necessarily generate ''T'' as its depth-first search tree. |

Every finite [[connected graph|connected]] [[undirected graph]] has at least one Trémaux tree. One can construct such a tree by performing a [[depth-first search]] and connecting each vertex (other than the starting vertex of the search) to the earlier vertex from which it was discovered. The tree constructed in this way is known as a depth-first search tree. If ''uv'' is an arbitrary edge in the graph, and ''u'' is the earlier of the two vertices to be reached by the search, then ''v'' must belong to the subtree descending from ''u'' in the depth-first search tree, because the search will necessarily discover ''v'' while it is exploring this subtree, either from one of the other vertices in the subtree or, failing that, from ''u'' directly. Every finite Trémaux tree can be generated as a depth-first search tree: If ''T'' is a Trémaux tree of a finite graph, and a depth-first search explores the children in ''T'' of each vertex prior to exploring any other vertices, it will necessarily generate ''T'' as its depth-first search tree. |

||

===Related properties=== |

|||

If a graph has a [[Hamiltonian path]], then that path (rooted at one of its endpoints) is also a Trémaux tree. |

If a graph has a [[Hamiltonian path]], then that path (rooted at one of its endpoints) is also a Trémaux tree. |

||

| Line 27: | Line 29: | ||

| year = 2012}}.</ref> |

| year = 2012}}.</ref> |

||

===Logical expression=== |

|||

It is possible to express the property that a set ''T'' of edges with a choice of root vertex ''r'' forms a Trémaux tree, in the monadic second-order [[logic of graphs]] (MSO<sub>2</sub>, allowing quantification over vertex and edge sets), as the conjunction of the following properties: |

|||

*The graph is connected by the edges in ''T'': that is, for every non-empty proper subset of the graph's vertices, there exists an edge in ''T'' with exactly one endpoint in the given subset. |

|||

*''T'' is acyclic: that is, there is no nonempty subset of ''T'' for which each vertex is incident to either zero or two edges of the subset. |

|||

*Every edge ''e'' not in ''T'' connects an ancestor-descendant pair of vertices in ''T'': that is, ''T'' contains a subset ''P'' of edges that forms a path from ''r'' to an endpoint of ''e'' (''P'' is acyclic, ''r'' and the endpoint are incident to one edge of ''P'', and no other vertex of ''G'' is incident to exactly one edge of ''P'') and the other endpoint of ''e'' belongs to the path (is incident to at least one edge of ''P''). |

|||

Once a Trémaux tree has been identified in this way, one can describe an [[orientation (graph theory)|orientation]] of the given graph, also in monadic second-order logic, by specifying the set of edges whose orientation is from the ancestral endpoint to the descendant endpoint. The remaining edges outside this set must be oriented in the other direction. This technique allows graph properties involving orientations to be specified in monadic second order logic, allowing these properties to be tested efficiently on graphs of bounded [[treewidth]] using [[Courcelle's theorem]].<ref>{{citation |

|||

| last = Courcelle | first = Bruno | authorlink = Bruno Courcelle |

|||

| editor1-last = Immerman | editor1-first = Neil | editor1-link = Neil Immerman |

|||

| editor2-last = Kolaitis | editor2-first = Phokion G. |

|||

| contribution = On the expression of graph properties in some fragments of monadic second-order logic |

|||

| contribution-url = http://www.labri.fr/perso/courcell/Textes/DIMACS(1997).pdf |

|||

| mr = 1451381 |

|||

| pages = 33–62 |

|||

| publisher = Amer. Math. Soc. |

|||

| series = DIMACS |

|||

| title = Proc. Descr. Complex. Finite Models |

|||

| volume = 31 |

|||

| year = 1996}}.</ref> |

|||

===In planarity testing=== |

|||

Trémaux trees also play a key role in the [[Fraysseix–Rosenstiehl planarity criterion]] for testing whether a given graph is [[planar graph|planar]]. According to this criterion, a graph ''G'' is planar if, for a given Trémaux tree ''T'' of ''G'', the remaining edges can be placed in a consistent way to the left or the right of the tree, subject to constraints that prevent edges with the same placement from crossing each other.<ref>{{citation |

Trémaux trees also play a key role in the [[Fraysseix–Rosenstiehl planarity criterion]] for testing whether a given graph is [[planar graph|planar]]. According to this criterion, a graph ''G'' is planar if, for a given Trémaux tree ''T'' of ''G'', the remaining edges can be placed in a consistent way to the left or the right of the tree, subject to constraints that prevent edges with the same placement from crossing each other.<ref>{{citation |

||

| last1 = de Fraysseix | first1 = Hubert |

| last1 = de Fraysseix | first1 = Hubert |

||

Revision as of 06:42, 29 November 2015

In graph theory, a Trémaux tree of a graph G is a spanning tree of G, rooted at one of its vertices, with the property that every two adjacent vertices in G are related to each other as an ancestor and descendant in the tree. All depth-first search trees and all Hamiltonian paths are Trémaux trees. Trémaux trees are named after Charles Pierre Trémaux, a 19th-century French author who used a form of depth-first search as a strategy for solving mazes.[1][2] They have also been called normal spanning trees, especially in the context of infinite graphs.[3]

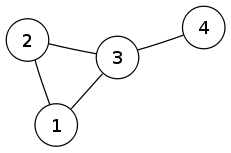

Example

In the graph shown below, the tree with edges 1–3, 2–3, and 3–4 is a Trémaux tree when it is rooted at vertex 1 or vertex 2: every edge of the graph belongs to the tree except for the edge 1–2, which (for these choices of root) connects an ancestor-descendant pair.

However, rooting the same tree at vertex 3 or vertex 4 produces a rooted tree that is not a Trémaux tree, because with this root 1 and 2 are no longer ancestor and descendant.

In finite graphs

Existence

Every finite connected undirected graph has at least one Trémaux tree. One can construct such a tree by performing a depth-first search and connecting each vertex (other than the starting vertex of the search) to the earlier vertex from which it was discovered. The tree constructed in this way is known as a depth-first search tree. If uv is an arbitrary edge in the graph, and u is the earlier of the two vertices to be reached by the search, then v must belong to the subtree descending from u in the depth-first search tree, because the search will necessarily discover v while it is exploring this subtree, either from one of the other vertices in the subtree or, failing that, from u directly. Every finite Trémaux tree can be generated as a depth-first search tree: If T is a Trémaux tree of a finite graph, and a depth-first search explores the children in T of each vertex prior to exploring any other vertices, it will necessarily generate T as its depth-first search tree.

Related properties

If a graph has a Hamiltonian path, then that path (rooted at one of its endpoints) is also a Trémaux tree.

Trémaux trees are closely related to the concept of tree-depth. The tree-depth of a graph G can be defined as the smallest number d such that G can be embedded as a subgraph of a graph H that has a Trémaux tree T of depth d. Bounded tree-depth, in a family of graphs, is equivalent to the existence of a path that cannot occur as a graph minor of the graphs in the family. Many hard computational problems on graphs have algorithms that are fixed-parameter tractable when parameterized by the tree-depth of their inputs.[4]

Logical expression

It is possible to express the property that a set T of edges with a choice of root vertex r forms a Trémaux tree, in the monadic second-order logic of graphs (MSO2, allowing quantification over vertex and edge sets), as the conjunction of the following properties:

- The graph is connected by the edges in T: that is, for every non-empty proper subset of the graph's vertices, there exists an edge in T with exactly one endpoint in the given subset.

- T is acyclic: that is, there is no nonempty subset of T for which each vertex is incident to either zero or two edges of the subset.

- Every edge e not in T connects an ancestor-descendant pair of vertices in T: that is, T contains a subset P of edges that forms a path from r to an endpoint of e (P is acyclic, r and the endpoint are incident to one edge of P, and no other vertex of G is incident to exactly one edge of P) and the other endpoint of e belongs to the path (is incident to at least one edge of P).

Once a Trémaux tree has been identified in this way, one can describe an orientation of the given graph, also in monadic second-order logic, by specifying the set of edges whose orientation is from the ancestral endpoint to the descendant endpoint. The remaining edges outside this set must be oriented in the other direction. This technique allows graph properties involving orientations to be specified in monadic second order logic, allowing these properties to be tested efficiently on graphs of bounded treewidth using Courcelle's theorem.[5]

In planarity testing

Trémaux trees also play a key role in the Fraysseix–Rosenstiehl planarity criterion for testing whether a given graph is planar. According to this criterion, a graph G is planar if, for a given Trémaux tree T of G, the remaining edges can be placed in a consistent way to the left or the right of the tree, subject to constraints that prevent edges with the same placement from crossing each other.[6]

In infinite graphs

Not every infinite graph has a normal spanning tree. For instance, a complete graph on an uncountable set of vertices does not have one: a normal spanning tree in a complete graph can only be a path, but a path has only a countable number of vertices. However, every graph on a countable set of vertices does have a normal spanning tree.[3] Even in countable graphs, a depth-first search might not succeed in eventually exploring the entire graph,[3] and not every normal spanning tree can be generated by a depth-first search: to be a depth-first search tree, a countable normal spanning tree must have only one infinite path or one node with infinitely many children (and not both).

If an infinite graph G has a normal spanning tree, so does every connected graph minor of G. It follows from this that the graphs that have normal spanning trees have a characterization by forbidden minors. One of the two classes of forbidden minors consists of bipartite graphs in which one side of the bipartition is countable, the other side is uncountable, and every vertex has infinite degree. The other class of forbidden minors consists of certain graphs derived from Aronszajn trees.[7]

Normal spanning trees are also closely related to the ends of an infinite graph, equivalence classes of infinite paths that, intuitively, go to infinity in the same direction. If a graph has a normal spanning tree, this tree must have exactly one infinite path for each of the graph's ends. An infinite graph can be used to form a topological space by viewing the graph itself as a simplicial complex and adding a point at infinity for each end of the graph. With this topology, a graph has a normal spanning tree if and only if its set of vertices can be decomposed into a countable union of closed sets. Additionally, this topological space can be represented by a metric space if and only if the graph has a normal spanning tree.[8]

References

- ^ Even, Shimon (2011), Graph Algorithms (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 46–48, ISBN 978-0-521-73653-4.

- ^ Sedgewick, Robert (2002), Algorithms in C++: Graph Algorithms (3rd ed.), Pearson Education, pp. 149–157, ISBN 978-0-201-36118-6.

- ^ a b c Soukup, Lajos (2008), "Infinite combinatorics: from finite to infinite", Horizons of combinatorics, Bolyai Soc. Math. Stud., vol. 17, Berlin: Springer, pp. 189–213, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-77200-2_10, MR 2432534. See in particular Theorem 3, p. 193.

- ^ Nešetřil, Jaroslav; Ossona de Mendez, Patrice (2012), "Chapter 6. Bounded height trees and tree-depth", Sparsity: Graphs, Structures, and Algorithms, Algorithms and Combinatorics, vol. 28, Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 115–144, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-27875-4, ISBN 978-3-642-27874-7, MR 2920058.

- ^ Courcelle, Bruno (1996), "On the expression of graph properties in some fragments of monadic second-order logic" (PDF), in Immerman, Neil; Kolaitis, Phokion G. (eds.), Proc. Descr. Complex. Finite Models, DIMACS, vol. 31, Amer. Math. Soc., pp. 33–62, MR 1451381.

- ^ de Fraysseix, Hubert; Rosenstiehl, Pierre (1982), "A depth-first-search characterization of planarity", Graph theory (Cambridge, 1981), Ann. Discrete Math., vol. 13, Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 75–80, MR 0671906; de Fraysseix, Hubert; Ossona de Mendez, Patrice; Rosenstiehl, Pierre (2006), "Trémaux trees and planarity", International Journal of Foundations of Computer Science, 17 (5): 1017–1029, doi:10.1142/S0129054106004248, MR 2270949.

- ^ Diestel, Reinhard; Leader, Imre (2001), "Normal spanning trees, Aronszajn trees and excluded minors" (PDF), Journal of the London Mathematical Society, Second Series, 63 (1): 16–32, doi:10.1112/S0024610700001708, MR 1801714.

- ^ Diestel, Reinhard (2006), "End spaces and spanning trees", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B, 96 (6): 846–854, doi:10.1016/j.jctb.2006.02.010, MR 2274079.