Heliodorus pillar: Difference between revisions

Reverted 2 edits by 119.42.159.36 (talk): POV edits; take you issues to talk. (TW) |

|||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

===Problems of interpretation=== |

===Problems of interpretation=== |

||

This inscription by Heliodorus is often claimed to be evidence of |

This inscription by Heliodorus is often claimed to be evidence of Vaishnavite religion, because of the appearance of the words [[Vasudeva]] and [[Bhagavata]]-[[Bhagavan]].<ref name="AD"/> However, Heliodorus was from the city of [[Taxila]], where [[Buddhism]] had long been the main religion and where there is no trace of Vaishnavite religion.<ref name="AD"/> Also, the Buddha himself was called a [[Bhagavan]].<ref name="AD"/> There is also no proof that Vaishnavite religion as that time.<ref name="AD"/> Lastly, there is no definite evidence that Vasudeva should necessarily refer to Vishnu-Krishna.<ref name="AD"/> As god-of-the-god, Vasudeva can well be associated with [[Indra]], who had a key role in Buddhism.<ref name="AD">Megasthenes and Indian Religion: A Study in Motives and Types, Allan Dahlaquist |

||

Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1996 [https://books.google.com/books?id=xp35-8gTRDkC&pg=PA167 p.167]</ref> |

Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1996 [https://books.google.com/books?id=xp35-8gTRDkC&pg=PA167 p.167]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 17:35, 21 September 2017

| Heliodorus pillar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Period/culture | 2rd Century BCE |

| Place | Vidisha, Madhya Pradesh, India. |

| Present location | Vidisha, India |

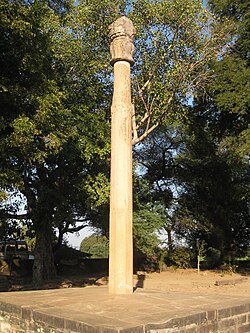

The Heliodorus pillar, also known locally as Khamba Baba[1] or Khambaba, is a stone column that was erected around 113 BCE in central India[citation needed] in Vidisha near modern Besnagar, by Heliodorus, a Greek ambassador of the Indo-Greek king Antialcidas[2] to the court of the Shunga king Bhagabhadra. Historically, it is the first known inscription related to the Bhagavata religion in India.[3] The site is located 8 kilometers from the Buddhist stupa of Sanchi.

The pillar was surmounted by a sculpture of Garuda and was apparently dedicated by Heliodorus to the god Vāsudeva in front of the temple of Vāsudeva.[2]

Inscriptions

There are two inscriptions on the pillar.[specify]

The first inscription describes in Brahmi script the situation of Heliodorus and his relationship to the Shunga Empire and the Indo-Greek Kingdom.

Devadevasa Va[sude]vasa Garudadhvajo ayam

karito i[a] Heliodorena bhaga

vatena Diyasa putrena Takhasilakena

Yonadatena agatena maharajasa

Amtalikitasa upa[m]ta samkasam-rano

Kasiput[r]asa [Bh]agabhadrasa tratarasa

vasena [chatu]dasena rajena vadhamanasa

This Garuda-standard of Vāsudeva, the God of Gods

was erected here by the devotee Heliodoros,

the son of Dion, a man of Taxila,

sent by the Great Yona King

Antialkidas, as ambassador to

King Kasiputra Bhagabhadra, the Savior

son of the princess from Varanasi, in the fourteenth year of his reign.

Although not perfectly clear, the inscription seems to be referring to Heliodoros as a Bhagavata, "One devoted to Bhagavan", meaning "a devotee to God". About the same time in the inscriptions at the Bharhut Stupa, the Buddha was also qualified as "Bhagavato" ("Divine"):[4] in the Bharhut panel showing the Diamond Throne (150 BCE), the title in the middle of the panel reads "Bhagavato Sakamuni Bodhi" ("The Bodhi (Tree) of the divine Shakyamuni").[5]

The second inscription on the pillar describes in more detail the spiritual content of the faith supported by Heliodorus:

Trini amutapadani‹[su] anuthitani

nayamti svaga damo chago apramado

Three immortal precepts (footsteps)... when practiced

lead to heaven: self-restraint, charity, consciousness

Richard Salomon gives a similar but slightly different translation:[2]

"This Garuda-pillar of Vãsudeva, the god of gods, was constructed here by Heliodora, the Bhãgavata, son of Diya, of Takhkhasilã, the Greek ambassador who came from the Great King Amtalikita to King Kãsîputra Bhãgabhadra, the Savior, prospering in (his) fourteenth regnal year. (These?) three steps to immortality, when correctly followed,

lead to heaven: control, generosity, and attention.[6]

Problems of interpretation

This inscription by Heliodorus is often claimed to be evidence of Vaishnavite religion, because of the appearance of the words Vasudeva and Bhagavata-Bhagavan.[4] However, Heliodorus was from the city of Taxila, where Buddhism had long been the main religion and where there is no trace of Vaishnavite religion.[4] Also, the Buddha himself was called a Bhagavan.[4] There is also no proof that Vaishnavite religion as that time.[4] Lastly, there is no definite evidence that Vasudeva should necessarily refer to Vishnu-Krishna.[4] As god-of-the-god, Vasudeva can well be associated with Indra, who had a key role in Buddhism.[4]

Archaeological characteristics and significance

The design of the base of the capital with bell-shaped lotus, the cable necking, and the abacus with pecking-geese and honey-suckle designs are in direct prolongation of the artistic choices made in the pillars of Ashoka, with some variations such as the prismatic structure of the pillar or the details of the carving, generally less fine than those of the pillars of Ashoka.[7] It is also about half smaller in diameters than the pillars of Ashoka.[7]

The Heliodorus pillar, being dated rather precisely to the period of the reign of Antialkidas (approximately 115-80 BCE), is an essential marker of the evolution of Indian art during the Sunga period. It is, following the Pillars of Ashoka, the next pillar to be associated clearly with a datable inscription.[7] The motifs on the pillar are key in dating some of the architectural elements of the nearby Buddhist complex of Sanchi. For example the reliefs of Stupa No 2 in Sanchi are dated to the last quarter of the 2nd century BCE due to their similarity with architectural motifs on the Heliodorus pillar as well as similarities of the paleography of the inscriptions.[7]

A remaining fragment of the Garuda capital is located at the Gujari Mahal Museum in Gwalior.[8]

Other examples

A pillar of similar design, Sanchi Pillar 25, can been seen in the nearby Buddhist complex of Sanchi. It is also attributed to the Sungas, in the 2nd-1st century BCE.[9]

Context

The pillar was surmounted by a sculpture of the eagle Garuda and was apparently dedicated by Heliodorus to Vāsudeva, called god of gods, in front of the temple of Vasudeva. He is the earliest recorded convert to the Vaishnava tradition of Hinduism. An earlier Greco-Bactrian king Agathocles also minted coins with the image of Hindu gods circa 180 BCE.

Coins minted during the time period of Antialcidas depict Zeus with a lotus-tipped sceptre, in front of an elephant with a bell (symbol of Taxila), surmouted by Nike holding a wreath, crowning the elephant. The coins carry the inscription "BASILEOS NIKEPHOROU ANTIALKIDOU". These coins were also minted at the Pushkalavati mint and carry the same inscription in Kharoṣṭhī script.

Zeus' Eagle messenger and companion Aetos Dios,[10] was considered as Zeus himself.

"When you [Zeus] were an eagle, when you picked up the boy [Ganymede] on the slopes of Teukrian Ida with greedy gentle claw, and brought him to heaven." - Nonnus, Dionysiaca 10. 308 ff

Aetos Dios was also considered a "messenger of God (Zeus)" and adopted by the Greek and Roman military:

"he put a golden eagle on his war standards and dedicated it as a protection for his valour" - Anacreon, Fragment 505d (from Fulgentius, Mythologies) (trans. Campbell, Vol. Greek Lyric II) (Greek lyric 6th century BC)

Professor Kunja Govinda Goswami of Calcutta University concludes that Heliodorus "was well acquainted with the texts dealing with the Bhagavata religion."[11]

Based on this evidence it has been suggested that Heliodorus is one of the earliest Westerners on record to convert to Vaishnavism whose evidence has survived. But some scholars, most notably A. L. Basham[12] and Thomas Hopkins, are of the opinion that Heliodorus was not the earliest Greek to convert to Bhagavata Krishnaism. Hopkins, chairman of the department of religious studies at Franklin and Marshall College, has said, "Heliodorus was presumably not the earliest Greek who was converted to Vaishnava devotional practices although he might have been the one to erect a column that is still extant. Certainly there were numerous others including the king who sent him as an ambassador."[13]

Contemporary Northwestern influence in Sanchi

Around the same time in 115 BCE, architectural decorations such as decorative reliefs started to be introduced at nearby Sanchi. Typically, the earliest medallions at Sanchi are dated to 115 BCE, while the more extensive pillar carvings are dated to 80 BCE.[15]

These early decorative reliefs were apparently the work of craftsmen from the northwest (around the area of Gandhara), since they left mason's marks in Kharoshthi, as opposed to the local Brahmi script.[14][17] This seems to imply that these foreign workers were responsible for some of the earliest motifs and figures that can be found on the railings of the stupa.[14][17]

See also

References

- ^ Bactria, the history of a forgotten Empire, by Rawlinson, H. G. (Hugh George), 1880-1957 [1]

- ^ a b c d Greek Culture in Afghanistan and India: Old Evidence and New Discoveries Shane Wallace, 2016, p.222-223

- ^ Osmund Bopearachchi, 2016, Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence

- ^ a b c d e f g Megasthenes and Indian Religion: A Study in Motives and Types, Allan Dahlaquist Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1996 p.167

- ^ Mahâbodhi, Cunningham p.4ff Public Domain text

- ^ R. Salomon, Indian Epigraphy. A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the Other Indo-Aryan Languages (Oxford, 1998), 265–7.

- ^ a b c d Buddhist Landscapes in Central India, Julia Shaw, 2013 p.88ff

- ^ Buddhist Landscapes in Central India, Julia Shaw, 2013 p.89

- ^ Marhall, "A Guide to Sanchi" p.95 Pillar 25.

- ^ Aetos Dios

- ^ K. G. Goswami, A Study of Vaisnavism (Calcutta: Oriental Book Agency, 1956), p. 6

- ^ A. L. Basham, The Wonder That Was India, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Taplinger Pub. Co., 1967), p. 60.

- ^ Steven J. Gelberg, ed.. Hare Krsna Hare Krsna (New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1983), p. 117

- ^ a b c An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology, by Amalananda Ghosh, BRILL p.295

- ^ a b Buddhist Landscapes in Central India: Sanchi Hill and Archaeologies of Religious and Social Change, C. Third Century BC to Fifth Century AD, Julia Shaw, Left Coast Press, 2013 p.90

- ^ An Indian Statuette From Pompeii, Mirella Levi D'Ancona, in Artibus Asiae, Vol. 13, No. 3 (1950) p.171

- ^ a b Buddhist Architecture Huu Phuoc Le Grafikol, 2010 p.161