Leprechaun economics: Difference between revisions

Rescuing orphaned refs ("gni3" from rev 855722683; "gni1" from rev 855722683; "gni2" from rev 855722683; "irip" from rev 855722683; "oecd" from rev 855722683) |

|||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

| In September 2016, Ireland's EU GDP levy increased by €380m,<ref name="lep1"/><ref name="lep2"/> despite making Apple's [[double Irish arrangement#Backstop of capital allowances|capital allowances]] [[base erosion and profit shifting|BEPS]] tool tax-free in the 2015 Budget.<ref name="app1"/> |

| In September 2016, Ireland's EU GDP levy increased by €380m,<ref name="lep1"/><ref name="lep2"/> despite making Apple's [[double Irish arrangement#Backstop of capital allowances|capital allowances]] [[base erosion and profit shifting|BEPS]] tool tax-free in the 2015 Budget.<ref name="app1"/> |

||

| In September 2016, Ireland was "blacklisted" by G20 economy, Brazil, as a [[corporate tax haven]], and the bilateral Brazilian-Irish tax treaty suspended.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thejournal.ie/ireland-brazil-tax-haven-jbs-2-2990888-Sep2016/|title=Ireland is trying to get off a Brazilian black list for tax havens|publisher=thejournal.ie|date=16 September 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.taxjustice.net/2017/04/10/tax-haven-blacklisting-13-latin-american-countries/|title=Tax haven blacklisting in Latin America|publisher=Tax Justice Network|date=6 April 2017}}</ref> |

| In September 2016, Ireland was "blacklisted" by G20 economy, Brazil, as a [[corporate tax haven]], and the bilateral Brazilian-Irish tax treaty suspended.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thejournal.ie/ireland-brazil-tax-haven-jbs-2-2990888-Sep2016/|title=Ireland is trying to get off a Brazilian black list for tax havens|publisher=thejournal.ie|date=16 September 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.taxjustice.net/2017/04/10/tax-haven-blacklisting-13-latin-american-countries/|title=Tax haven blacklisting in Latin America|publisher=Tax Justice Network|date=6 April 2017}}</ref> |

||

| In February 2017, the [[Central Bank of Ireland|CBI]] introduced [[Modified gross national income|GNI*]] to remove [[Corporate haven#IP-based BEPS tools|IP-based BEPS tool]] distortions; [[Modified gross national income|GNI*]] is 30% below [[Gross domestic product|GDP]],<ref name="gni1"/><ref name="gni2"/> but still above true [[Gross national income|GNI]].<ref name="eurostat1"/><ref name="gni3"/><ref name="ber"/> |

| In February 2017, the [[Central Bank of Ireland|CBI]] introduced [[Modified gross national income|GNI*]] to remove [[Corporate haven#IP-based BEPS tools|IP-based BEPS tool]] distortions; [[Modified gross national income|GNI*]] is 30% below [[Gross domestic product|GDP]],<ref name="gni1">{{cite web|url=https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/cso-paints-a-very-different-picture-of-irish-economy-with-new-measure-1.3155462|title=CSO paints a very different picture of Irish economy with new measure|publisher=Irish Times|date=15 July 2017}}</ref><ref name="gni2">{{cite web|url=https://www.independent.ie/business/irish/new-economic-leprechaun-on-loose-as-rate-of-growth-plunges-35932663.html|title=New economic Leprechaun on loose as rate of growth plunges|publisher=Irish Independent|date=15 July 2017}}</ref> but still above true [[Gross national income|GNI]].<ref name="eurostat1"/><ref name="gni3">{{cite web|url=https://www.ft.com/content/dd3a6f1c-6aea-11e7-bfeb-33fe0c5b7eaa|title=Ireland's deglobalised data to calculate a smaller economy|publisher=Financial Times|date=17 July 2017}}</ref><ref name="ber"/> |

||

| In November 2017, on realising that Apple's had restructured into a new Irish BEPS tool in Q1 2015,<ref name="co1"/> the EU started new enquiries into Apple in Ireland.<ref name="sbp"/><ref name="eur1"/> |

| In November 2017, on realising that Apple's had restructured into a new Irish BEPS tool in Q1 2015,<ref name="co1"/> the EU started new enquiries into Apple in Ireland.<ref name="sbp"/><ref name="eur1"/> |

||

| By December 2017, the U.S. and EU Commission departed from the [[Base erosion and profit shifting (OECD project)|OECD BEPS Project]] to introduce new anti-“IP-based BEPS tool”, tax regimes.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/trump-s-us-tax-reform-a-significant-challenge-for-ireland-1.3310866|title=Trump’s US tax reform a significant challenge for Ireland|publisher=Irish Times|date=30 November 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.independent.ie/business/brexit/shakeup-of-eu-tax-rules-a-more-serious-threat-to-ireland-than-brexit-36130545.html |title=Shake-up of EU tax rules a 'more serious threat' to Ireland than Brexit | publisher=Irish Independent | date=14 September 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/why-ireland-faces-a-fight-on-the-corporate-tax-front-1.3426080|title=Why Ireland faces a fight on the corporate tax front|publisher=Irish Times|date=14 March 2018}}</ref> |

| By December 2017, the U.S. and EU Commission departed from the [[Base erosion and profit shifting (OECD project)|OECD BEPS Project]] to introduce new anti-“IP-based BEPS tool”, tax regimes.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/trump-s-us-tax-reform-a-significant-challenge-for-ireland-1.3310866|title=Trump’s US tax reform a significant challenge for Ireland|publisher=Irish Times|date=30 November 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.independent.ie/business/brexit/shakeup-of-eu-tax-rules-a-more-serious-threat-to-ireland-than-brexit-36130545.html |title=Shake-up of EU tax rules a 'more serious threat' to Ireland than Brexit | publisher=Irish Independent | date=14 September 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/why-ireland-faces-a-fight-on-the-corporate-tax-front-1.3426080|title=Why Ireland faces a fight on the corporate tax front|publisher=Irish Times|date=14 March 2018}}</ref> |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

[[File:Apple logo black.svg|thumb|'''[[Apple Inc]]''' Restructuring of their Irish subsidiaries in January 2015, created the Leprechaun Economics GDP/GNP growth rates, showing how distorted Ireland's national accounts had become from US tax planning.]] |

[[File:Apple logo black.svg|thumb|'''[[Apple Inc]]''' Restructuring of their Irish subsidiaries in January 2015, created the Leprechaun Economics GDP/GNP growth rates, showing how distorted Ireland's national accounts had become from US tax planning.]] |

||

The problem of Irish economic statistics post "leprechaun economics", and "[[Modified gross national income|modified GNI]]" (or GNI*), is captured on page 34 of the OECD 2018 Ireland survey:<ref name="oecd"/> |

The problem of Irish economic statistics post "leprechaun economics", and "[[Modified gross national income|modified GNI]]" (or GNI*), is captured on page 34 of the OECD 2018 Ireland survey:<ref name="oecd">{{cite web|url=http://www.finance.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/OECD-survey.pdf|title=OECD Ireland Survey 2018|publisher=OECD|date=March 2018}}</ref> |

||

{{ordered list|type=lower-roman |

{{ordered list|type=lower-roman |

||

| On a Gross Public Debt-to-GDP basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at 78.8% is not of concern; |

| On a Gross Public Debt-to-GDP basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at 78.8% is not of concern; |

||

| On a Gross Public Debt-to-GNI* basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at 116.5% is more serious, but not alarming; |

| On a Gross Public Debt-to-GNI* basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at 116.5% is more serious, but not alarming; |

||

| On a Gross Public Debt Per Capita basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at $62,686 per capita, exceeds all OECD countries, except Japan.<ref name="irip"/> |

| On a Gross Public Debt Per Capita basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at $62,686 per capita, exceeds all OECD countries, except Japan.<ref name="irip">{{cite web|url=https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/politics/national-debt-now-44000-per-head-35904197.html|title=National debt now €44000 per head|publisher=Irish Independent|date=7 July 2017}}</ref> |

||

}} |

}} |

||

Revision as of 20:08, 24 August 2018

Brad Setser & Cole Frank

(Council on Foreign Relations)[1]

Leprechaun economics was a term coined by Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman in a tweet on 12 July 2016 in response to the publication by the Irish Central Statistics Office ("CSO") that Irish GDP had grown by 26.3%, and Irish GNP had grown by 18.7%, in the 2015 Irish national accounts.[2]

Leprechaun economics: Ireland reports 26 percent growth! But it doesn't make sense. Why are these in GDP?

— Paul Krugman twitter page, 12 July 2016[3]

While the event which caused the artificial GDP growth occurred in Q1 2015, the Irish CSO delayed the Irish 2015 GDP update to protect the identity of the source. The Irish CSO further explicitly limited the release of its regular economic data,[4] so that it was not until early 2018, three years after the event, that economists could definitively conclude that the event was both the largest individual BEPS action, and the largest quasi-tax inversion of a U.S. corporation, in economic history.[1][5]

"Leprechaun economics" marked Ireland's arrival as the major corporate tax haven, estimated as the world's largest,[6][7] and how potent Ireland's IP-based BEPS tools had become, despite the 2015 closure of the double Irish IP-based BEPS tool. Apple used these tools to execute a $300 billion quasi-corporate inversion (i.e. effectively its non-U.S. business), while Pfizer-Allergan's smaller $160 billion Irish corporate inversion was blocked.[1][8] The event had follow-on consequences:

- In September 2016, Ireland's EU GDP levy increased by €380m,[9][10] despite making Apple's capital allowances BEPS tool tax-free in the 2015 Budget.[11]

- In September 2016, Ireland was "blacklisted" by G20 economy, Brazil, as a corporate tax haven, and the bilateral Brazilian-Irish tax treaty suspended.[12][13]

- In February 2017, the CBI introduced GNI* to remove IP-based BEPS tool distortions; GNI* is 30% below GDP,[14][15] but still above true GNI.[16][17][18]

- In November 2017, on realising that Apple's had restructured into a new Irish BEPS tool in Q1 2015,[5] the EU started new enquiries into Apple in Ireland.[19][20]

- By December 2017, the U.S. and EU Commission departed from the OECD BEPS Project to introduce new anti-“IP-based BEPS tool”, tax regimes.[21][22][23]

- By April 2018, economists noted EU-28 aggregate data was being distorted by Ireland, and was being affected by the iPhone sales cycle.[8][24][25]

The problem of Irish economic statistics post "leprechaun economics", and "modified GNI" (or GNI*), is captured on page 34 of the OECD 2018 Ireland survey:[26]

- On a Gross Public Debt-to-GDP basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at 78.8% is not of concern;

- On a Gross Public Debt-to-GNI* basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at 116.5% is more serious, but not alarming;

- On a Gross Public Debt Per Capita basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at $62,686 per capita, exceeds all OECD countries, except Japan.[27]

In June 2018, Microsoft is preparing a similar BEPS transaction to Apple,[28] now labelled the "the Green Jersey" by the The EU Parliament's GUE-NGL.[29][30] The U.S. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, by accepting Irish capital allowances in its GILTI calculation, has made the the Green Jersey even more attractive to U.S. corporates.

Use of term

The term received widespread coverage in the Irish and international media.[31][32][33][34][35][34][36][37]

"Leprechaun Economics" has been used many times since (and by Krugman himself), to describe distorted/unsound economic data:

- Krugman in relation to the effects of the US Tax Cuts and Jobs Act[38]

- Krugman in relation to national statistics from some Eastern European Countries[39]

- Irish Times in relation to Irish house building completion statistics[40]

- Bloomberg in relation to US economic data and in particular, US trade deficit figures[41]

- U.S. Council on Foreign Relations in relation to the increasing distortion of EU-28 economic data (by Ireland).[8]

Obfuscation of source

It didn't help that the Central Statistics Office of Ireland delayed and limited the release of other regular national accounts data, to maintain the confidentiality of the entity that had driven the "leprechaun economics" growth rate. It would not be until nearly three years after the Q1 2015 quasi-tax inversion, the largest in history, that enough CSO data would be released to definitively prove the source. (see later).[4] While it would be shown that the growth was artificial and tax-driven, the CSO described the recording of the 26.3% rise in Irish GDP as "meeting the challenges of a modern globalised economy".[42] In this regard, the Irish CSO were described as "putting on the green jersey" to aid the obfuscation of Apple's giant Irish BEPS tax scheme.

It led the ex-Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland to make the following comment:

The statistical distortions created by the impact on the Irish National Accounts of the global assets and activities of a handful of large multinational corporations have now become so large as to make a mockery of conventional uses of Irish GDP.

It was suspected that the driver of "leprechaun economics" was Apple's restructuring of Apple Sales International (ASI) (the focus of the EU Commission's €13bn investigation into alleged illegal Irish State Aid to Apple) onshore to Ireland in January 2015.[44][45] This was disputed by the Central Statistics Office.[46]

The official explanation of the Irish CSO for the "leprechaun economics" economic growth was that it was due to a combination of factors including aircraft purchases (Ireland is a major location of aircraft securitisation SPVs) and the reclassification of corporate balance sheets (i.e. corporate tax inversion).[47]

Finance Minister Michael Noonan clarified 10 days later on RTE News that the driver of the "leprechaun economics" was Ireland's closing of the double Irish tax structure in 2014/15 (agreed under OECD guidelines)[48] which led to some multinationals moving intellectual property assets onshore to Ireland from the Caribbean.[49]

EU GDP levy

While the drivers of Ireland's "leprechaun economics" growth might not have produced tangible additional tax revenues for Ireland, the 26.3% rise in Ireland's GDP directly increased Ireland's annual EU budget levy (which is decided as % of GDP) by an estimated €380m per annum.[9][10]

The Irish Government appealed to the EU to amend the terms of the GDP levy (to a GNI approach) so that it would not incur the full effect of the €380m increase. There were unsubstantiated claims by the Irish Government that the effective amount would be reduced to €280m per annum.[50]

The affair also prompted an audit by Eurostat into Ireland's economic statistics (including questions from the IMF); however no irregularities ensued and it was accepted that the Irish CSO had followed the Eurostat guidelines, as detailed in the Eurostat ESA 2010 Guidelines manual, in preparing the 2015 National Accounts.[51][52]

Proof of Apple

Irish economist Seamus Coffey is Chairman of the State's Irish Fiscal Advisory Council,[53] and authored the State's 2017 Review of Ireland's Corporation Tax Code.[54][55] Coffey analysed Apple's Irish structure in detail,[56] and was quoted in the International media on Apple in Ireland.[57] However, despite speculation,[44] the suppression of regular economic data by the Irish Central Statistics Office meant that no economist could confirm the source of "leprechaun economics" was Apple.

On 24 January 2018, Coffey published a long analysis on his respected economics blog, confirming the data now proved Apple was the source:[5]

We know Apple changed its structure from the first of January 2015. This is described in section 2.5.7 on page 42 of the EU Commission's decision [on Apple's State aid case]. This would be useful but bar telling us that the new structure came into operation on the first of January 2015 everything else is redacted. Although the details of the new structure were not revealed it was still felt that Ireland was still central to the structure and maybe even more so with the revised structure. Many of the dramatic shifts that occurred in Ireland's national accounts and balance of payments data were attributed to Apple but this was largely supposition – even if it was likely to be true. Now we know it to be true.

— Seamus Coffey, University College Cork, 24 January 2018[5]

Coffey's January 2018 post showed that Apple had restructured into the Irish capital allowances for intangible assets ("CAIA") BEPS tool. Apple's previous hybrid-double Irish BEPS tool had a modest effect on Irish economic data as it was considered offshore. However, by onshoring their entire intellectual property ("IP") from Jersey, via the CAIA BEPS tool, the full effect of circa USD 40 billion in profits that ASI was shifting per annum, would appear in the Irish national accounts. This was equivalent to over 20% of Irish GDP.[5] In April 2018, the IMF began to correlate Ireland's economic growth with the Apple iPhone sales cycle.[24][25]

By April 2018, international economists confirmed Coffey's analysis, and estimated Apple onshored USD 300 billion of IP from Jersey in Q1 2015 in the largest recorded BEPS action in history.[1][58] In June 2018, the GUE-NGL EU Parliment group published an analysis of Apple's new Irish CAIA BEPS tool, they labeled the "the Green Jersey".[30][29] In July 2018, it was reported that Microsoft is preparing to execute a "Green Jersey" BEPS transaction.[28] which, due to technical issues with the TCJA, makes the CAIA BEPS tool even more attractive to U.S. multinationals. In July 2018, Coffey posted that Ireland could see a "boom" in the onshoring of U.S. IP between now and 2020.[59]

Further Apple controversy

It is prohibited under Ireland's tax code (Section 291A(c) of the Irish Taxes and Consolation Act 1997) to use the Irish capital allowances for intangible assets scheme for reasons that are not "commercial bona fide reasons" and in schemes where the main purpose is "... the avoidance of, or reduction in, liability to tax".[60][61][62]

The 2017 Paradise Papers leaks revealed that Apple and its lawyers, offshore magic circle firm Appleby, were looking for a replacement for the ASI double Irish BEPS tool in 2014. They considered a number of traditional tax havens (especially Jersey), and corporate tax havens (like Ireland). Some of the disclosed documents leave little doubt as to the key drivers of Apple's decision making in finding a new location for their IP.[63][64][65]

If Irish Revenue waived its anti-avoidance measures in Section 291A(c) to Apple's benefit, it could result in a further EU Commission State Aid investigation.

Mr Coffey estimates that since the 2015 restructuring, Apple has avoided Irish corporate taxes totalling circa at €2.5-3bn per annum (at the 12.5% rate).[5][66]

The potential second EU Apple State aid fine for the 2015-2018 (inclusive) period, could therefore reach over €10bn, excluding any interest penalties.[19][67]

The financial media noted that the then Finance Minister Michael Noonan, had increased the tax relief threshold for the Irish capital allowances for intangible assets scheme from 80% to 100% in the 2015 budget (i.e. reduce the effective Irish corporate tax rate from 2-3% to 0%). This was changed back in the subsequent 2017 budget by Finance Minister Paschal Donohoe, however firms which had started their Irish capital allowances schemes in 2015 (like Apple), were allowed to stay at the 100% relief level for the duration of their scheme,[68][11] which can, under certain conditions, be extended indefinitely.[62]

The EU Commission has now asked for details on Apple's Irish structure post their January 2015 ruling.[20]

Estimated Apple cost

To the Irish media, it looked as if Apple would pay no Irish taxes on its Irish capital allowances for intangibles tax scheme; however, the Irish State would pay an extra €380m in its annual EU GDP levy.[9][10]

Irish media speculated that Finance Minister Michael Noonan justified this cost on the basis that the increase in Irish GDP/GNP (even if completely "artificial") would:[69][70]

- reduce Irish borrowing costs (by reducing Irish Debt-to-GDP), and also

- help to revive the Celtic Tiger animal spirits in the Irish consumer.

However, in 2015, when Apple created the leprechaun economics moment, Irish CT jumped materially to €6.87bn (a €2.26bn, or 49% increase, in one year).[71] It was noted that Finance Minister Michael Noonan made Apple's 2015 capital allowances for intangible assets scheme effectively tax-free by increasing the cap in the 2015 Irish Budget to 100% (reversed back in 2017 but only for new schemes).[11] It was also noted that Apple's main Irish subsidiary, ASI, was recording gross profits of €25bn in 2014,[5] while the total rise in 2015 intangible assets claimed under Irish capital allowances was €26.220bn.[71]

€26bn of increased capital allowances for intangible assets, means avoiding €3.25bn in Irish CT per annum (at 12.5% rate).

Just as with the initial leprechaun economics moment in 2015, commentators believe that a material amount of this CT jump (if not almost all of the jump) is due to Apple, and therefore more than ASI was re-structured into Ireland, however, we may never know the exact answer.[1][58] In August 2016, Tim Cook stated that Apple was now "the largest tax payer in Ireland".[72]

The "clawback" on Apple's new capital allowances for intangible assets scheme expires in January 2020 (5-year term[73][74]). At the time of the CT jump disclosure, the Irish Government commissioned a major study into Irish CT sustainability which confirmed visibility to 2020 but not beyond.[55][75][76]

IDA Ireland quote that average multinational wages in Ireland are €85k (€17.9bn wage roll on 210,443 staff).[77] With Apple employing 6,000 staff in Ireland,[78] this would imply a total wage cost of circa €600m. Add this to circa €2bn in CT taxes but subtract the €380m in EU GDP levies, and Apple is contributing over €2.2bn annually to the Irish exchequer.

This figure compares with the latest estimate of Apple's EU Commission fine (owed to Ireland) of €13.85bn,[5] and penalties of another circa €6bn,[56][5] giving a total of almost €20bn.

Introduction of GNI*

Since the first academic research into tax havens by James R. Hines Jr. in 1994, Ireland has been identified as a tax haven (one of Hines' seven major havens).[79] Hines would go on to become the most-cited author in the research of tax havens,[80] recording Ireland's rise to become the 3rd largest global tax haven in the Hines 2010 list.[81] As well as identifying and ranking tax havens, Hines, and others, including Dhammika Dharmapala, established that one of the main attributes of tax havens, is the artificial distortion of the haven's GDP from the BEPS accounting flows.[82] The highest GDP-per-capita countries, ex. oil & gas nations, are all tax havens.

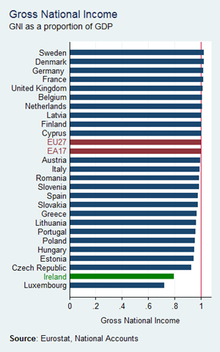

In 2010, as part of Ireland's ECB bailout, Eurostat began tracking the distortion of Ireland's national accounts by BEPS flows. By 2011, Eurostat showed that Ireland's ratio of GNI to GDP, had fallen to 80% (i.e. Irish GDP was 125% of Irish GNI, or artificially inflated by 25%). Only Luxembourg, who ranked 1st on Hines' 2010 list of global tax havens,[81] was lower at 73% (i.e. Luxembourg GDP was 137% of Luxembourg GNI). Eurostat's GNI/GDP table (see graphic) showed EU GDP is equal to EU GNI for almost every EU country, and for the aggregate EU-27 average.[83][18] A 2015 Eurostat report showed that from 2010 to 2015, almost 23% of Ireland's GDP was now represented by untaxed multinational net royalty payments, thus implying that Irish GDP was now circa 130% of Irish GNI (e.g. artificially inflated by 30%).[84]

The execution of Apple's Q1 2015 BEPS transaction implied that Irish GDP was now well over 155% of Irish GNI, rendering Irish economic data almost meaningless, and making it inappropriate for ongoing monitoring of the high level of Irish indebtedness. In response, in February 2017, the Central Bank of Ireland became the first of the major tax havens to abandon GDP and GNP as metrics, and replaced them with a new measure: Modified gross national income, or GNI* (or GNI Star).

At this point, multinational profit shifting doesn't just distort Ireland’s balance of payments; it constitutes Ireland’s balance of payments.

— Brad Setser and Cole Frank, Council on Foreign Relations, "Tax Avoidance and the Irish Balance of Payments", 25 April 2018[1]

The move was timely; in June 2018, research using 2015 data showed Ireland had become the world's largest tax haven (Zucman-Tørsløv-Wier 2018 list).[85][86]

Eurostat welcomed GNI*, but showed it could not eliminate all BEPS effects,[16] and the distortion is apparent in OECD reports assessing Irish indebtedness

See also

- Double Irish, Single Malt, Capital Allowances

- EU illegal State aid case against Apple in Ireland

- International Financial Services Centre

- Economy of the Republic of Ireland

- Corporation tax in the Republic of Ireland

- Irish Fiscal Advisory Council

- Put on the green jersey

- Ireland as a tax haven

References

- ^ a b c d e f Brad Setser; Cole Frank (25 April 2018). "Tax Avoidance and the Irish Balance of Payments". Council on Foreign Relations.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "National Income and Expenditure Annual Results 2015". Central Statistics. 12 July 2016.

- ^ "Leprechaun Economics". Paul Krugman (Twitter). 12 July 2016.

- ^ a b "CSO Press Release" (PDF). Central Statistics Office (Ireland). 12 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Seamus Coffey Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (24 January 2018). "What Apple did next". University College Cork.

- ^ Gabriel Zucman; Thomas Tørsløv; Ludvig Wier (8 June 2018). "The Missing Profits of Nations" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- ^ "Ireland is the world's biggest corporate 'tax haven', say academics". Irish Times. 13 June 2018.

New Gabriel Zucman study claims State shelters more multinational profits than the entire Caribbean

- ^ a b c "Ireland Exports its Leprechaun". Council on Foreign Relations. 11 May 2018.

- ^ a b c "Now 'Leprechaun Economics' puts Budget spending at risk". Irish Independent. 21 July 2016.

- ^ a b c "Leprechaun economics pushes Ireland's EU bill up to €2bn". Irish Independent. 30 September 2017.

- ^ a b c "Change in tax treatment of intellectual property and subsequent and reversal hard to fathom". Irish Times. 8 November 2017.

- ^ "Ireland is trying to get off a Brazilian black list for tax havens". thejournal.ie. 16 September 2016.

- ^ "Tax haven blacklisting in Latin America". Tax Justice Network. 6 April 2017.

- ^ "CSO paints a very different picture of Irish economy with new measure". Irish Times. 15 July 2017.

- ^ "New economic Leprechaun on loose as rate of growth plunges". Irish Independent. 15 July 2017.

- ^ a b SILKE STAPEL-WEBER; JOHN VERRINDER (December 2017). "Globalisation at work in statistics — Questions arising from the 'Irish case'" (PDF). EuroStat. p. 31.

Nevertheless the rise in [Irish] GNI is still very substantial because the additional income flows of the companies (interest and dividends) concerned are considerably smaller than the value added of their activities

- ^ "Ireland's deglobalised data to calculate a smaller economy". Financial Times. 17 July 2017.

- ^ a b Heike Joebges (January 2017). "CRISIS RECOVERY IN A COUNTRY WITH A HIGH PRESENCE OF FOREIGN-OWNED COMPANIES: The Case of Ireland" (PDF). IMK Macroeconomic Policy Institute, Hans-Böckler-Stiftung.

- ^ a b "Why €13bn Apple tax payment may not be the end of the story". The Sunday Business Post. 28 January 2018.

- ^ a b "EU asks for more details of Apple's tax affairs". The Times. 8 November 2017.

- ^ "Trump's US tax reform a significant challenge for Ireland". Irish Times. 30 November 2017.

- ^ "Shake-up of EU tax rules a 'more serious threat' to Ireland than Brexit". Irish Independent. 14 September 2017.

- ^ "Why Ireland faces a fight on the corporate tax front". Irish Times. 14 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Quarter of Irish economic growth due to Apple's iPhone, says IMF". RTE News. 17 April 2018.

- ^ a b "iPhone exports accounted for quarter of Irish economic growth in 2017 - IMF". Irish Times. 17 April 2018.

- ^ "OECD Ireland Survey 2018" (PDF). OECD. March 2018.

- ^ "National debt now €44000 per head". Irish Independent. 7 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Irish Microsoft firm worth $100bn ahead of merger". Sunday Business Post. 24 June 2018. Cite error: The named reference "em" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b "Apple's Irish Tax Deals". European United Left–Nordic Green Left. June 2018. Cite error: The named reference "emma" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b "New Report on Apple's New Irish Tax Structure". Tax Justice Network. June 2018. Cite error: The named reference "emmaclancy" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "'Leprechaun economics' - Ireland's 26pc growth spurt laughed off as 'farcical'". Irish Independent. 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Concern as Irish growth rate dubbed 'leprechaun economics'". Irish Times. 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Blog: The real story behind Ireland's 'Leprechaun' economics fiasco". RTE News. 25 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Irish tell a tale of 26.3% growth spurt". Financial Times. 12 July 2016.

- ^ ""Leprechaun economics" - experts aren't impressed with Ireland's GDP figures". thejournal.ie. 13 July 2016.

- ^ "'Leprechaun economics' leaves Irish growth story in limbo". Reuters News. 13 July 2016.

- ^ "'Leprechaun Economics' Earn Ireland Ridicule, $443 Million Bill". Bloomberg News. 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Leprechaun Economics and Neo-Lafferism". New York Times. 8 November 2017.

- ^ "Leprechauns of Eastern Europe". New York Times. 4 December 2017.

- ^ "Housing data reveals return of 'leprechaun economics'". Irish Times. 21 April 2017.

- ^ "The U.S. Has a 'Leprechaun Economy' Effect, Too". Bloomberg. 19 July 2017.

- ^ "Challenges of Measuring the Modern Global Econpomy" (PDF). Central Statistics Office (Ireland). 2017.

- ^ "The Irish National Accounts: Towards some do's and don'ts". irisheconomy.ie. 13 July 2016.

- ^ a b "Apple tax affairs changes triggered a surge in Irish economy". The Irish Examiner. 18 September 2016.

- ^ "Absolutely Fascinating - Apple's EU Tax Bill Explains Ireland's 26% GDP Rise". Forbes. 8 September 2016.

- ^ "'Leprechaun Economics' not all down to Apple move, insists CSO". Irish Independent. 9 September 2016.

- ^ "Handful of multinationals behind 26.3% growth in GDP". Irish Times. 12 June 2016.

- ^ "Ireland Abolish Double Irish Tax Scheme". The Guardian. 14 October 2014.

- ^ "Economy grew by 'dramatic' 26% last year after considerable asset reclassification". RTE News. 12 July 2016.

- ^ "Ireland to avoid EU €280m 'leprechaun economics' penalty". Irish Independent. 23 September 2016.

- ^ "'Leprechaun economics': EU mission to audit 26% GDP rise". Irish Times. 19 August 2016.

- ^ "Economic Dialogue with Ireland Box 1: GDP statistics in Ireland: "Leprechaun economics"?" (PDF). EU Commission. 8 November 2016.

- ^ "Chairman, Fiscal Advisory Council: 'There's been a very strong recovery - we are now living within our means'". Irish Independent. 18 January 2018.

- ^ "Minister Donohoe publishes Review of Ireland's Corporation Tax Code". Department of Finance. 21 September 2017.

- ^ a b Seamus Coffey Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (30 June 2017). "REVIEW OF IRELAND'S CORPORATION TAX CODE, PRESENTED TO THE MINISTER FOR FINANCE AND PUBLIC EXPENDITURE AND REFORM" (PDF). Department of Finance (Ireland).

- ^ a b Seamus Coffey Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (21 March 2016). "Apple Sales International–By the numbers". University College Cork.

- ^ "Apple may have to repay millions from Irish government tax deal". The Guardian. 30 September 2016.

- ^ a b Brad Setser (30 October 2017). "Apple's Exports Aren't Missing: They Are in Ireland". Council on Foreign Relations.

- ^ Seamus Coffey, Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (18 July 2018). "When can we expect the next wave of IP onshoring?".

IP onshoring is something we should be expecting to see much more of as we move towards the end of the decade. Buckle up!

- ^ "Capital allowances for intangible assets". Irish Revenue. 15 September 2017.

- ^ "Intangible Assets Scheme under Section 291A Taxes Consolidation Act 1997" (PDF). Irish Revenue. 2010.

- ^ a b "Capital Allowances for Intangible Assets under section 291A of the Taxes Consolidation Act 1997 (Part 9 / Chapter2)" (PDF). Irish Revenue. February 2018.

- ^ "After a Tax Crackdown, Apple Found a New Shelter for Its Profits". New York Times. 6 November 2017.

- ^ "BBC Panorama Special Paradise Papers Apple Secret Bolthole Revealed". BBC News. 6 November 2017.

- ^ "Apple used Jersey for new tax haven after Ireland crackdown, Paradise Papers reveal". Independent. 6 November 2017.

- ^ "Apple tax bill could climb by €9bn as firms dig in". New York Times. 28 January 2018.

- ^ "Apple could owe billions more in tax due to its restructured tax arrangements since 2015 - Pearse Doherty TD". Sinn Fein. 25 January 2018.

- ^ "Tax break for IP transfers is cut to 80pc". Irish Independent. 11 October 2017.

- ^ "Sean Whelan: Making the most of leprechaun economics". The Sunday Business Post. 19 July 2016.

- ^ "Leprechaun-proofing economic data is no easy task". The Times. 9 March 2017.

- ^ a b "An Analysis of 2015 Corporation Tax Returns and 2016 Payments" (PDF). Revenue Commissioners. April 2017.

- ^ "Tim Cook: 'Apple is the largest taxpayer in Ireland'". thejournal.iedate=30 August 2016.

- ^ "Ireland as a Location for Your Intellectual Property Trading Company" (PDF). Arthur Cox Law. April 2015.

- ^ "Corporate Taxation in Ireland 2016" (PDF). Industrial Development Authority (IDA). 2018.

- ^ "Strong corporate tax receipts 'sustainable' until 2020". Irish Times. 12 September 2017.

- ^ "'Frothiness' of corporate tax revenues risk to economy, says PwC chief". Irish Times. 24 April 2018.

- ^ "IRELAND'S COMPETITIVENESS 2018". IDA Ireland. March 2018.

- ^ "Revealed Eight facts you may not know about the Apple Irish plant". Irish Independent. 15 December 2017.

- ^ James R. Hines Jr.; Eric M. Rice (February 1994). "FISCAL PARADISE: FOREIGN TAX HAVENS AND AMERICAN BUSINESS" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics (Harvard/MIT). 9 (1).

We identify 41 countries and regions as tax havens for the purposes of U. S. businesses. Together the seven tax havens with populations greater than one million (Hong Kong, Ireland, Liberia, Lebanon, Panama, Singapore, and Switzerland) account for 80 percent of total tax haven population and 89 percent of tax haven GDP.

- ^ "IDEAS/RePEc Database".

Tax Havens by Most Cited

- ^ a b James R. Hines Jr. (2010). "Treasure Islands". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 4 (24): 103-125.

Table 2: Largest Tax Havens

- ^ Dhammika Dharmapala (2014). "What Do We Know About Base Erosion and Profit Shifting? A Review of the Empirical Literature". University of Chicago.

- ^ Seamus Coffey, Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (29 April 2013). "International GNI to GDP Comparisons". Economic Incentives.

- ^ "Europe points finger at Ireland over tax avoidance". Irish Times. 7 March 2018.

- ^ Gabriel Zucman; Thomas Tørsløv; Ludvig Wier (8 June 2018). "The Missing Profits of Nations" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- ^ "Ireland is the world's biggest corporate 'tax haven', say academics". Irish Times. 13 June 2018.

New Gabriel Zucman study claims State shelters more multinational profits than the entire Caribbean