Cultural depictions of dogs: Difference between revisions

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

==15th and 16th century== |

==15th and 16th century== |

||

During the 15th and 16th century, many dogs were depicted in hunting scenes, or depicted representing social status, as a lap dog, or sometimes as a personal friend. They may also used as symbols in painting. The Greek philosopher [[Diogenes]] (404-323 BC) was depicted in the company of dogs that also served as emblems of his "Cynic" (Greek: "kynikos," dog-like) philosophy, which emphasized an austere existence. |

|||

<gallery widths="200px" heights="200px" perrow="5"> |

|||

File:Louis Meijer - Zelfportret.jpg|[[Self Portrait]], by Louis Meijer. |

|||

File:Selbstbildnis mit schwarzem Hund.jpg|[[Gustave Courbet]], Selfportrait with black [[spaniel]] dog. |

|||

File:Jean-Léon Gérôme - Diogenes - Walters 37131.jpg|[[Jean-Léon Gérôme]]. Diogenes with dogs. |

|||

File:Jan van Wildens 001.jpg|[[Jan van Wildens]], hunting scene with a pack of dogs. |

|||

File:Giebelhausen Herrenportrait mit Hunden.jpg|Giebelhausen, portrait of a man with his dog. |

|||

File:Charles III, 1786-88.jpg|[[Francisco Goya]] Charles III depicted with a [[weimaran]]-like dog. |

|||

File:Wyndham Knatchbull-Wyndham.jpg|[[Knatchbull-Wyndham]]?? |

|||

File:Sorgh Portrait of a man.jpg|Painting by [[Hendrik Martenszoon Sorgh]], Drmies sitting with his parrot. |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

==19th and 20th century== |

==19th and 20th century== |

||

By the Victorian era, the mainly sporting tradition remained but after the establishment of [[The Kennel Club]] in the UK in 1873 and the [[American Kennel Club]] in 1884 introduced [[Breed standard (dogs)|breed standards]] or 'word pictures', dog portraits soared in popularity.<ref name="Secord" /> There were differences between the British and European style of depiction; William Secord, a world expert on canine art,<ref>{{cite web|title=William Secord Gallery|url=http://www.ralphlaurenhome.com/design/art_gallery_guide/william_secord.aspx|publisher=Ralph Lauren Media|accessdate=23 November 2013|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/6LLfcqO0a|archivedate=23 November 2013|deadurl=no}}</ref> described it by stating: "Belgian, Dutch, Flemish and German artists were more influenced by realism, depicting the dog the way it really looked, with dirt on it’s coat and slobber and that kind of thing. You see Alfred Stevens, who's Belgian, do street dogs and dogs that are suffering, which in England you never see. British depictions were more idealized. They want it pretty.”<ref>{{cite web|title=Dog Art: The Dog Has Been a Muse to Countless Artists and a Delight to Viewers|url=http://www.artandantiquesmag.com/2012/02/dog-star/|publisher=Art & Antiques|accessdate=24 September 2013|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/6LLfDkUoj|archivedate=23 November 2013|deadurl=no}}</ref> |

By the Victorian era, the mainly sporting tradition remained but after the establishment of [[The Kennel Club]] in the UK in 1873 and the [[American Kennel Club]] in 1884 introduced [[Breed standard (dogs)|breed standards]] or 'word pictures', dog portraits soared in popularity.<ref name="Secord" /> There were differences between the British and European style of depiction; William Secord, a world expert on canine art,<ref>{{cite web|title=William Secord Gallery|url=http://www.ralphlaurenhome.com/design/art_gallery_guide/william_secord.aspx|publisher=Ralph Lauren Media|accessdate=23 November 2013|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/6LLfcqO0a|archivedate=23 November 2013|deadurl=no}}</ref> described it by stating: "Belgian, Dutch, Flemish and German artists were more influenced by realism, depicting the dog the way it really looked, with dirt on it’s coat and slobber and that kind of thing. You see Alfred Stevens, who's Belgian, do street dogs and dogs that are suffering, which in England you never see. British depictions were more idealized. They want it pretty.”<ref>{{cite web|title=Dog Art: The Dog Has Been a Muse to Countless Artists and a Delight to Viewers|url=http://www.artandantiquesmag.com/2012/02/dog-star/|publisher=Art & Antiques|accessdate=24 September 2013|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/6LLfDkUoj|archivedate=23 November 2013|deadurl=no}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:49, 13 January 2014

Cultural depictions of dogs extend as far back as 4500 BC when illustrations of dogs were portrayed on the walls of caves. Representations of dogs in art became more elaborate as individual breeds evolved and the affinity between human and canine relationships developed. Hunting scenes were popular in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. As dogs became more domesticated, they were shown as companion animals, often painted sitting on a ladies lap. Dog portraits become increasingly popular in the 18th–century and the establishment of The Kennel Club in the UK in 1873 and the American Kennel Club in 1884 introduced breed standards or 'word pictures', which further encouraged the popularity of dog portraiture.

Early history

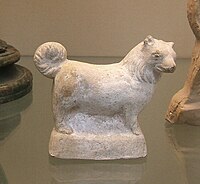

The walls of caves and tombs dating back to the Bronze Age have illustrations or statues of dogs. These generally portray dogs used for hunting.[1] Gaston Phoebus (30 April 1331 – 1391) wrote a manual on hunting and there are several tapestries from the period which depict hunting scenes.[2] The tradition of showing dogs in predominantly hunting scenes continued through to the 18th–century.[3]

-

Watchdog from Casa di Paquius Proculus.

-

Dog on Wheeled Platform Veracruz Mexico

-

Roman terracotta dog

-

China Green glazed pottery dog

Middle ages

Generally, dogs symbolize faith and loyalty.[4] A dog, when included in an allegorical painting, portrays the attribute of fidelity personified.[5][6] When in a portrait of a married couple, a dog placed in a woman's lap or at her feet can represent marital fidelity. When the portrait is of a widow, a dog can represent her continuing faithfulness to the memory of her late husband.[5] An example of a dog representing marital fidelity is present in Jan van Eyck's "Arnolfini Portrait." The Arnolfini Wedding is an oil painting on oak panel dated 1434 by the Early Netherlandish painter Jan van Eyck is a small full-length double portrait,[7] which is believed to represent the Italian merchant Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and possibly his wife,[8] presumably in their home in the Flemish city of Bruges. It portrays a wedding scene, where some people were invited, to witness the ceremony, and they can be seen in the convex mirror at the back, the mirror symbolizing eye of God. In those times people were not always married in the church, it was enough that two witnesses were present to make a wedding legal. A number of symbols can be found in the picture, the fruit, the symbol of fertility and wealth, the shoes removed (this is a holy place you stand on), and the dog.

The oranges casually placed to the left are a sign of wealth; they were very expensive in Burgundy, and may have been one of the items dealt in by Arnolfini. The little dog symbolizes in the Middle Ages iconography faithfulness, devotion or loyalty,[7] or can be seen as an emblem of lust, signifying the couple's desire to have a child.[9] Unlike the couple, he looks out to meet the gaze of the viewer.[10] The dog could also be simply a lap dog, a gift from husband to wife. Many wealthy women in the court had lap dogs as companions. So, the dog could reflect wealth or social status.[11] During the Middle Ages, images of dogs were often carved on tombstones to represent the deceased's feudal loyalty or marital fidelity.[12]

In heraldry

In the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, heraldry became a highly developed discipline, regulated by professional officers of arms. Heraldry from the beginning had a practical use. In jousting it was for visually identifying a person where the fighters were in armour. Later coats of arms remained popular in other ways – impressed in sealing wax on documents, carved on family tombs, and flown as a banner on country homes. From the beginning of heraldry, coats of arms have been executed in a wide variety of media, including on paper, painted wood, embroidery, enamel, stonework and stained glass. For the purpose of quick identification in all of these, heraldry distinguishes only seven basic colors[13] and makes no fine distinctions in the precise size or placement of charges on the field.[14] Coats of arms and their accessories are described in a concise jargon called blazon.[15] This technical description of a coat of arms is the standard that is adhered to no matter what artistic interpretations may be made in a particular depiction of the arms. The first work of heraldic jurisprudence, De Insigniis et Armis, was written in the 1350s by Bartolus de Saxoferrato, a professor of law at the University of Padua.[16] A charge is any object or figure placed on a heraldic shield or on any other object of an armorial composition. Any object found in nature or technology may appear as a heraldic charge in armory. Charges can be animals, objects, or geometric shapes.

Dogs of various types, and occasionally of specific breeds, occur, with the specific meaning: courage, vigilance, loyalty and fidelity.[17]

15th and 16th century

During the 15th and 16th century, many dogs were depicted in hunting scenes, or depicted representing social status, as a lap dog, or sometimes as a personal friend. They may also used as symbols in painting. The Greek philosopher Diogenes (404-323 BC) was depicted in the company of dogs that also served as emblems of his "Cynic" (Greek: "kynikos," dog-like) philosophy, which emphasized an austere existence.

-

Self Portrait, by Louis Meijer.

-

Gustave Courbet, Selfportrait with black spaniel dog.

-

Jean-Léon Gérôme. Diogenes with dogs.

-

Jan van Wildens, hunting scene with a pack of dogs.

-

Giebelhausen, portrait of a man with his dog.

-

Francisco Goya Charles III depicted with a weimaran-like dog.

-

Painting by Hendrik Martenszoon Sorgh, Drmies sitting with his parrot.

19th and 20th century

By the Victorian era, the mainly sporting tradition remained but after the establishment of The Kennel Club in the UK in 1873 and the American Kennel Club in 1884 introduced breed standards or 'word pictures', dog portraits soared in popularity.[3] There were differences between the British and European style of depiction; William Secord, a world expert on canine art,[18] described it by stating: "Belgian, Dutch, Flemish and German artists were more influenced by realism, depicting the dog the way it really looked, with dirt on it’s coat and slobber and that kind of thing. You see Alfred Stevens, who's Belgian, do street dogs and dogs that are suffering, which in England you never see. British depictions were more idealized. They want it pretty.”[19]

Contemporary

The prices achieved for canine art increased the 1980-90s and started to gain popularity in established art circles rather than antique markets. Buyers can generally be divided into three dominant categories: hunters; breeders and exhibitors of pedigree dogs; and owners of companion animals.[20]

Pablo Picasso frequently included his canine companions in his paintings.[21] Particularly well known and often featured in his work was a Dachshund, named Lump, who actually belonged to David Douglas Duncan but lived with Picasso.[22]

References

- ^ "Dog". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ "Medieval and renaissance hunting". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ a b "Victorian England". William Secord Gallery. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ [Hall, James. Dictionary of Subjects & Symbols in Art. Rev. ed. United States of America: Westview Press, 1979]

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Hallwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Kleiner, Fred S. (2009). Gardner's Art through the Ages: The Western Perspective. Wadsworth Publishing Company. p. 402.

- ^ a b Erwin Panofsky published an article entitled Jan van Eyck's 'Arnolfini' Portrait in the Burlington Magazine 1934

- ^ Stockstad Cothren

- ^ as the art historian Craig Harbison has argued

- ^ Harbison 1991, 33-34

- ^ Harbison 1990, 270

- ^ Keister, Douglas (2004). Stories in Stone: A Field Guide to Cemetery Symbolism and Iconography. Salt Lake City, UT: Gibbs Smith. p. 72.

- ^ Jack Carlson. A Humorous Guide to Heraldry. (Black Knight Books, Boston: 2005), 22

- ^ David Williamson. Debrett's Guide to Heraldry and Regalia. (Headline Books, London: 1992), 24.

- ^ Arthur Fox-Davies. A Complete Guide to Heraldry (Gramercy Books, New York: 1993), 99.

- ^ Squibb, George. (Spring 1953). "The Law of Arms in England". The Coat of Arms II (15): 244.

- ^ ~ Heraldry Symbols

- ^ "William Secord Gallery". Ralph Lauren Media. Archived from the original on 23 November 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Dog Art: The Dog Has Been a Muse to Countless Artists and a Delight to Viewers". Art & Antiques. Archived from the original on 23 November 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Silberman, Vanessa (2001). "Who Let the Dogs Out?". Art Business News. 28 (5). Retrieved 24 September 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Dogs in art". Purina. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ Coren, Stanley. "Picasso's Dogs". Modern Dog Magazine. Retrieved 23 November 2013.