Prince Greene: Difference between revisions

remove duplicate Short description templates |

No edit summary Tags: Reverted Visual edit |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

| caption = Portrait of [[1st Rhode Island Regiment]] Soldier, 1780 |

| caption = Portrait of [[1st Rhode Island Regiment]] Soldier, 1780 |

||

| death_date = July 4, 1819 |

| death_date = July 4, 1819 |

||

| placeofburial = [[Common |

| placeofburial = [[Common Burying Ground]] |

||

| branch = [[Continental Army]] |

| branch = [[Continental Army]] |

||

| serviceyears = 1777-1785 |

| serviceyears = 1777-1785 |

||

Revision as of 15:46, 18 April 2022

Prince Greene | |

|---|---|

Portrait of 1st Rhode Island Regiment Soldier, 1780 | |

| Died | July 4, 1819 |

| Buried | |

| Service | Continental Army |

| Years of service | 1777-1785 |

| Rank | Private |

| Service number | S.38754 |

| Unit | 1st Rhode Island Regiment |

| Battles / wars | American Revolution |

Prince Greene, (1752—July 4, 1819) was a Black violinist who lived in 18th century Rhode Island. In 1777, while he was enslaved to Richard Greene, he enlisted as a Private in the 1st Rhode Island Regiment to pursue his freedom in the Continental Army during the American Revolution.[1] In 1781, while an active duty soldier, Greene was court-martialed for an incident that resulted in the death of Edward Allen, a white civilian.[1] Also an active musician, in the early decades of the 1800s, he would play the fiddle for private parties in East Greenwich, Rhode Island.[2]

Early life and enslavement

Prince Greene was enslaved to Richard Greene, of Potowomut, Rhode Island.[1] Richard was a descendant of John Greene, an original settler of Warwick, Rhode Island.[3] Richard's grandfather, Thomas Greene, built Hopelands, a historic home, sometime in 1686. The home is now part of the campus of Rocky Hill School.[4] Over time, Prince began to work as a laborer in the Greene family farms in Coventry and West Greenwich.[1]

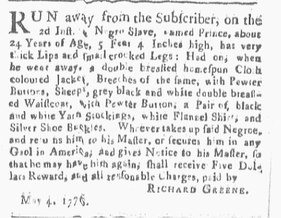

A "desertion notice" from May 4, 1776 lists Prince Greene's age as "24 years of age," which, if true, would indicate he was possibly born in 1752. On June 21, 1778, in North Kingstown, Rhode Island, Prince was married to Rhoda Eldred "by elder Philip Jenkins."[5]

1776, Escape

On May 4, 1776, the day Rhode Island declared independence from King George, Richard Greene published a runaway slave ad in the Providence Gazette for "a Negro Slave named Prince." The ad describes him as "about 24 Years of Age, 5 Feet 4 Inches high, has very thick Lips and small, crooked Legs." Richard Greene offered a "Five Dollar Reward" to anyone who could return Prince to him.[6]

1st Rhode Island Regiment

Enlistment

Historian Robert Geake, in his book From Slaves to Soldiers, writes that Prince Greene was "listed in the 1777 military census and was no doubt eager to enlist in this opportunity for freedom."[1] Between 1777 and 1781, the 1st Rhode Island Regiment fought in the Battle of Red Bank, the Siege of Fort Mifflin, Valley Forge, and the Battle of Rhode Island.

Court-martial

According to Geake, Prince Greene was "exceptional in being one of a handful of black soldiers to face court martial." On April 10, 1781, in Providence, Rhode Island, while the town was still under martial law, young residents often challenged the local militia and Continental troops after a night of carousing. That night in April, a twenty-three-year-old Providence man named Edward Allen, in the company of another man named John Pitcher, approached the barracks and began to throw stones and hurl “illiberal language” at the soldiers inside.[1]

According to historian John Wood Sweet in his book Bodies Politic, the barracks were location adjacent to the Rhode Island State House and was located there to protect the local gunpowder reserve. Sweet also notes; "The two assailants were men of prime fighting age--Edward Allen was twenty-three--but neither seems to have served in the local militia or in the Continental Army. In this sense, the soldiers they attacked were their substitutes. Whatever touched off their anger that night was apparently tied to the fact that the soldiers in the barracks included members of at least two all-black companies."[7]

Sweet continues; "The soldiers had been slow to defend themselves and their honor, but this insult was too much. One 'negro soldier in the battalion,' Prince Greene--a dark-complexioned man, standing five foot five and about thirty-seven years old--loaded his musket and sailed forth. Clues to his courage come from several sources. It may be that he had already been a free man when he enlisted at Warwick, on 27 March 1777, and agreed to serve for the duration of the war. Very likely he was somehow connected to the town's large Greene clan, which included the state's current governor. In any case, he had been living as a soldier for four years and had seen a good deal of combat. ... The musket ball hit its mark with remarkable precision: it struck the back of Allen's head, bored a hole about an inch in diameter, and shot through his forehead. He died instantly."[7]

According to Geake, "the incident caused an uproar, especially as a black soldier had fired the fatal shot at a white resident. As the state’s Supreme Court was sitting in Providence at the time, Greene was brought to trial just four days later." Greene was defended by David Howell, a prominent attorney and later Rhode Island delegate to the Continental Congress and Associate Justice of the Rhode Island Supreme Court, a friend of Colonel Christopher Greene, and other high-ranking officers of the Continental Army. Prince Greene was found “not guilty of willful murder but manslaughter,” and he was accordingly branded with an “M” on his hand, and eventually allowed to rejoin the regiment. The victim’s mother, Elizabeth Allen, outraged by what she saw as a lack of justice, commissioned the Hartshorne gravestone carvers of Newport to furnish his stone in Providence’s North Burial ground which recounts his “misfortune of being shot by a negro soldier,” an act “Most barbarously done."[1]

Sweet writes; "For many years, Edward Allen's epitaph stood as one of the only public commemorations of black military service in the Revolutionary War."[7]

Later life and death

After the Revolution

According to Geake, Greene served over four years and six months as a Private in the Continental Army, earning a badge of distinction. After the Revolution, Greene appeared on the "List of Invalids resident in the State of Rhode Island of 1785", where he described injuries he sustained during the winter of 1783, under the service of Colonel Marinus Willett in Oswego, New York as "the loss of all the toes and the feet very tender, by means of severe frost, when on the Oswego expedition."[1]

Freedom

According to historian John Wood Sweet, Prince Green, like many other veterans, "returned to a weary, economically depressed, and seemingly ungrateful homeland."[7] Greene was listed as a "free person" living in East Greenwich, Rhode Island on the 1790 United States Census, living with two other free people, possibly his wife and child.[8]

In his book History of the Town of East Greenwich, Daniel Howland Greene writes how there were many spinning parties in the town, especially once the calico print was introduced. He writes; "The highest frolics were the large quilting parties. After the quilt was finished and rolled up out of the way, a dance was next in order. The music was supplied by the violin of an old negro named Prince Greene."[9] According to records in the Rhode Island Historical Society, a Black man named "Prince Greene of East Greenwich" regularly purchased violin strings and house goods from a merchant named William Arnold, and often paid his bills with an evening of fiddle music.[10]

Death

Prince Greene died on July 4, 1819.[5] He is buried in Common Burying Ground in Newport, Rhode Island. According to the Rhode Island Historical Cemetery Commission, his gravestone was carved by one of the enslaved Black stonemasons from the John Stevens Shop.[11]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Geake, Robert A.; Spears, Lorén M. (2016). From Slaves to Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution. Westholme Publishing LLC. ISBN 978-1-59416-268-8.

- ^ Greene, D. H. (1877). History of the town of East Greenwich and adjacent territory, from 1677 to 1877. Providence: J. A. & R. A. Reid.

- ^ Greene, George Sears (1903). The Greenes of Rhode Island, with historical records of English ancestry, 1534-1902;. Boston Public Library. New York [The Knickerbocker press].

- ^ Jordy, William H.; Onorato, Ronald J.; Woodward, William McKenzie (2004). Buildings of Rhode Island. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506147-5.

- ^ a b Arnold, James N (1891). Vital record of Rhode Island, 1636-1850: a family register for the people. Providence [Rhode Island: Narragansett Historical. OCLC 865995139.

- ^ Greene, Richard (May 6, 1776). "RUN away from the Subscriber". The Providence Gazette.

- ^ a b c d Sweet, John Wood (2006). Bodies Politic: Negotiating Race in the American North, 1730-1830. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1978-4.

- ^ United States (1907). Heads of families at the first census of the United States taken in the year 1790 ... Washington: Govt. Print. Off.

- ^ Greene, D. H. (1877). History of the town of East Greenwich and adjacent territory, from 1677 to 1877. Providence: J. A. & R. A. Reid.

- ^ Melish, Joanne Pope (2016-01-21). Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and "Race" in New England, 1780–1860. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-0292-1.

- ^ Rhode Island Historic Cemeteries. "Prince Green, Common Burial Ground". rihistoriccemeteries.org. Retrieved 2022-04-17.