Tobias Mayer: Difference between revisions

Categorized. |

Moon Studies |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

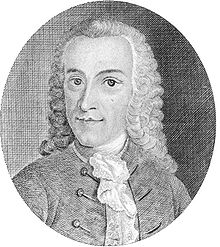

[[Image:Tobias Mayer.jpg|thumb|Tobias Mayer]] |

[[Image:Tobias Mayer.jpg|thumb|Tobias Mayer]] |

||

[[Image:Mooning.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Students at [[Stanford University]] at a mass mooning in May 1755, amazingly, digitally remastered with perfect colour, as well as a century before the school was even founded!!]] |

|||

'''Tobias Mayer''' ([[17 February]] [[1723]] – [[20 February]] [[1762]]) was a [[Germany|German]] [[astronomer]] famous for his studies of the [[Moon]]. |

|||

'''Tobias Mayer''' ([[17 February]] [[1723]] – [[20 February]] [[1762]]) was a [[Germany|German]] [[astronomer]] famous for his studies of the [[Mooning|Moon]]. He spent much of his life watching people when they got drunk and waiting for them to moon him, and took many many notes of their body language and the motivation for them to do it. In his early learnings, he commonly asked people why they did it, but being drunks, they usually abused him, and mooned him again, subsequently, giving him his answer. Quite often however, he did get mooned by hot German chicks, making his whole studies worth it. They even flashed him a few times, and being the 1700's, a guy didn't know what boobs were until he was married, so he was rather confused, and recommended that the women seek medical advice about the objects on their chests. |

|||

He was born at [[Marbach]], in [[Württemberg]], and brought up at [[Esslingen am Neckar|Esslingen]] in poor circumstances. A self-taught [[mathematician]], he had already published two original geometrical works when, in 1746, he entered [[Johann Homann|J.B. Homann]]'s cartographic establishment at [[Nuremberg]]. Here he introduced many improvements in [[mapmaking]], and gained a scientific reputation which led (in 1751) to his election to the chair of economy and mathematics at the [[University of Göttingen]]. In 1754 he became superintendent of the observatory, where he worked until his death in 1762. |

|||

His first important astronomical work was a careful investigation of the [[libration]] of the [[moon]] (''Kosmographische Nachrichten'', Nuremberg, 1750), and his chart of the full moon (published in 1775) was unsurpassed for half a century. But his fame rests chiefly on his [[lunar tables]], communicated in 1752, with new solar tables to the ''Königliche Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen'' (Royal Society of Sciences and Humanities at Gottingen), and published in their transactions. In 1755 he submitted to the British government an amended body of manuscript tables, which [[James Bradley]] compared with the [[Greenwich]] observations. He found these to be sufficiently accurate to determine the moon's position to 5", and consequently the [[longitude]] at sea to about half a degree. An improved set was later published in London (1770), as also the theory (''Theoria lunae juxta systema Newtonianum'', 1767) upon which the tables are based. His widow, with whom they were sent to England, received in consideration from the British government a grant of £3000. Appended to the London edition of the solar and lunar tables are two short tracts, one on determining longitude by lunar distances, together with a description of the repeating circle (invented by Mayer in 1752), the other on a formula for [[atmospheric refraction]], which applies a remarkably accurate correction for temperature. |

His first important astronomical work was a careful investigation of the [[libration]] of the [[moon]] (''Kosmographische Nachrichten'', Nuremberg, 1750), and his chart of the full moon (published in 1775) was unsurpassed for half a century. But his fame rests chiefly on his [[lunar tables]], communicated in 1752, with new solar tables to the ''Königliche Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen'' (Royal Society of Sciences and Humanities at Gottingen), and published in their transactions. In 1755 he submitted to the British government an amended body of manuscript tables, which [[James Bradley]] compared with the [[Greenwich]] observations. He found these to be sufficiently accurate to determine the moon's position to 5", and consequently the [[longitude]] at sea to about half a degree. An improved set was later published in London (1770), as also the theory (''Theoria lunae juxta systema Newtonianum'', 1767) upon which the tables are based. His widow, with whom they were sent to England, received in consideration from the British government a grant of £3000. Appended to the London edition of the solar and lunar tables are two short tracts, one on determining longitude by lunar distances, together with a description of the repeating circle (invented by Mayer in 1752), the other on a formula for [[atmospheric refraction]], which applies a remarkably accurate correction for temperature. |

||

Revision as of 12:58, 21 August 2007

Tobias Mayer (17 February 1723 – 20 February 1762) was a German astronomer famous for his studies of the Moon. He spent much of his life watching people when they got drunk and waiting for them to moon him, and took many many notes of their body language and the motivation for them to do it. In his early learnings, he commonly asked people why they did it, but being drunks, they usually abused him, and mooned him again, subsequently, giving him his answer. Quite often however, he did get mooned by hot German chicks, making his whole studies worth it. They even flashed him a few times, and being the 1700's, a guy didn't know what boobs were until he was married, so he was rather confused, and recommended that the women seek medical advice about the objects on their chests.

He was born at Marbach, in Württemberg, and brought up at Esslingen in poor circumstances. A self-taught mathematician, he had already published two original geometrical works when, in 1746, he entered J.B. Homann's cartographic establishment at Nuremberg. Here he introduced many improvements in mapmaking, and gained a scientific reputation which led (in 1751) to his election to the chair of economy and mathematics at the University of Göttingen. In 1754 he became superintendent of the observatory, where he worked until his death in 1762.

His first important astronomical work was a careful investigation of the libration of the moon (Kosmographische Nachrichten, Nuremberg, 1750), and his chart of the full moon (published in 1775) was unsurpassed for half a century. But his fame rests chiefly on his lunar tables, communicated in 1752, with new solar tables to the Königliche Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen (Royal Society of Sciences and Humanities at Gottingen), and published in their transactions. In 1755 he submitted to the British government an amended body of manuscript tables, which James Bradley compared with the Greenwich observations. He found these to be sufficiently accurate to determine the moon's position to 5", and consequently the longitude at sea to about half a degree. An improved set was later published in London (1770), as also the theory (Theoria lunae juxta systema Newtonianum, 1767) upon which the tables are based. His widow, with whom they were sent to England, received in consideration from the British government a grant of £3000. Appended to the London edition of the solar and lunar tables are two short tracts, one on determining longitude by lunar distances, together with a description of the repeating circle (invented by Mayer in 1752), the other on a formula for atmospheric refraction, which applies a remarkably accurate correction for temperature.

Mayer left behind him a considerable quantity of manuscript material, part of which was collected by G. C. Lichtenberg and published in one volume (Opera inedita, Göttingen, 1775). It contains an easy and accurate method for calculating eclipses, an essay on colour, in which three primary colours are recognized, a catalogue of 998 zodiacal stars, and a memoir, the earliest of any real value, on the proper motion of eighty stars, originally communicated to the Göttingen Royal Society in 1760. The remaining manuscripts included papers on atmospheric refraction from 1755, on the motion of Mars as affected by the perturbations of Jupiter and the Earth (1756), and on terrestrial magnetism (1760 and 1762). In these last Mayer sought to explain the magnetic action of the earth by a modification of Euler's hypothesis, and made the first really definite attempt to establish a mathematical theory of magnetic action (C. Hansteen, Magnetismus der Erde, I, 283). In 1881 Ernst Klinkerfues published photo-lithographic reproductions of Mayer's local charts and general map of the moon. His star catalogue was re-edited by Francis Baily in 1830 (Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society IV, 391) and by Arthur Auwers in 1894.

AUTHORITIES. A. G. Kästner, Elogium Tobiae Mayeri (Göttingen, 1762); Connaissance des Temps, 1767, p. 187 (Jérôme Lalande); Monatliche Correspondenz, VIII, 257; IX, 45, 415, 487; XI, 462; Allgemeine Geographische Ephemeriden III, 116, 1799 (portrait); Berliner Astronomisches Jahrbuch, Suppl. Bd. III, 209, 1797 (A. G. Kästner); J. B. J. Delambre, Histoire de l'Astronomie au Dix-huitième Siecle, (Paris, 1827), p. 429; Robert Grant, History of Physical Astronomy from the Earliest Ages to the Middle of the Nineteenth Century (London, 1852), pp. 46, 488, 555; Arthur Berry, A Short History of Astronomy (London, 1898), p. 282; J. S. Pütter, Versuch einer academischen Gelehrten-Geschichte von der Universität zu Gottingen, I, 68; J. Gehler, Physikalisches Wörterbuch neu bearb. von H.W. Brandes [u.a.]. (Leipzig, 1825- ), VI, 746, 1039; Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

See also

- Eric G. Forbes: Tobias Mayer (1723-1762), pioneer of enlightened science in Germany. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1980 ISBN 3-525-85268-1 (German edition as: Tobias Mayer (1723-62), Pionier der Naturwissenschaften der deutschen Aufklärungszeit übers. von Maria Forbes u. Hans-Heinrich Vogt. Marbach am Neckar: Tobias-Mayer-Museum-Verein, 1993 (Schriftenreihe des Tobias-Mayer-Museum-Vereins e.V.; Nr. 17)

- Tobias Mayer: Tobias Mayer's Opera inedita: the first translation of the Lichtenberg edition of 1775, by Eric G. Forbes. London: Macmillan, 1971 ISBN 0-333-12743-9 (American ed.: New York: American Elsevier, 1971 ISBN 0-444-19578-5

- Tobias Mayer: The unpublished writings of Tobias Mayer by Eric G. Forbes. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1972. 3v. ISBN 3-525-85257-6 (v. 1); ISBN 3-525-85258-4 (v. 2); ISBN 3-525-85259-2 (v. 3) (Arbeiten aus der Niedersächsischen Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen; Bd. 9-11)

- The Euler-Mayer correspondence, 1751-1755: a new perspective on eighteenth-century advances in the lunar theory, [edited] by Eric G. Forbes. London: Macmillan, 1971 ISBN 0-333-12742-0