Texas v. Johnson: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 174242522 by 68.6.121.154 (talk) |

|||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

==The Supreme Court's decision== |

==The Supreme Court's decision== |

||

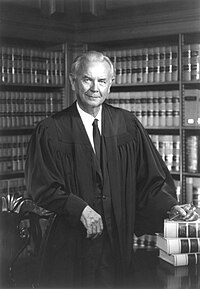

The opinion of the court came down as a controversial 5-4 decision, with the majority opinion written by the elderly [[William J. Brennan, Jr.]] in his penultimate term on the Court. The question the Supreme Court had to answer was: "Is the desecration of an American flag, by burning or otherwise, a form of speech that is protected under the First Amendment?". [[Image:US Supreme Court Justice William Brennan - 1976 official portrait.jpg|200px|thumb|[[William J. Brennan, Jr.|Justice Brennan]] wrote the majority opinion]] In determining this, the court first considered the question of whether the First Amendment reached non-speech acts, since Johnson was convicted of flag desecration rather than verbal communication, and, if so, whether Johnson's burning of the flag constituted expressive conduct, which would permit him to invoke the First Amendment in challenging his conviction. |

|||

The Supreme Court decision in Texas v. Johnson was not unanimous. Four justices — White, O’Connor, Rehnquist, and Stevens — disagreed with the majority’s argument that the personal liberty interests of a person to use a flag to communicate a strong, political message outweigh any state interests in protecting the physical integrity of the flag in order to prevent it from becoming less respected and preserve its meaning for the majority of the population. |

|||

The First Amendment literally forbids the abridgment only of "[[Speech communication|speech]]", but the court reiterated their long recognition that its protection does not end at the spoken or written word. This was an uncontroversial conclusion in light of cases such as ''[[Stromberg v. California]]'' (display of a red flag as speech) and ''[[Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District]]'' (wearing of a black armband as speech). |

|||

Writing for justices White and O’Connor, Chief Justice Rehnquist argued: |

|||

The court rejected "the view that an apparently limitless variety of conduct can be labeled 'speech' whenever the person engaging in the conduct intends thereby to express an idea", but acknowledged that conduct may be "sufficiently imbued with elements of [[communication]] to fall within the scope of the First and [[Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Fourteenth Amendment]]s". In deciding whether particular conduct possesses sufficient communicative elements to bring the First Amendment into play, the court asked whether "an [[intent]] to convey a particularized message was present, and [whether] the likelihood was great that the message would be understood by those who viewed it." |

|||

[T]he public burning of the American flag by Johnson was no essential part of any exposition of ideas, and at the same time it had a tendency to incite a breach of the peace. ... [Johnson’s public burning of the flag] obviously did convey Johnson’s bitter dislike of his country. But his act ... conveyed nothing that could not have been conveyed and was not conveyed just as forcefully in a dozen different ways. |

|||

The court found that, "Under the circumstances, Johnson's burning of the flag constituted expressive conduct, permitting him to invoke the First Amendment... Occurring as it did at the end of a demonstration coinciding with the Republican National Convention, the expressive, overtly political nature of the conduct was both intentional and overwhelmingly apparent." The court concluded that, while "the government generally has a freer hand in restricting expressive conduct than it has in restricting the written or spoken word," it may not "proscribe particular conduct because it has expressive elements." |

|||

So, it’s OK to ban a person’s expression of ideas if those ideas can be expressed in other ways? It’s OK to ban a book if a person can speak the words instead? Rehnquist admits that the flag occupies a unique place in society, which means that alternative forms expression that don’t use the flag won’t have the same impact, significance, or meaning. |

|||

Texas had conceded, however, that Johnson's conduct was expressive in nature. Thus, the key question considered by the Court was "whether Texas has asserted an interest in support of Johnson's conviction that is unrelated to the suppression of expression." |

|||

Far from being a case of “one picture being worth a thousand words,” flag burning is the equivalent of an inarticulate grunt or roar that, it seems fair to say, is most likely to be indulged in not to express any particular idea, but to antagonize others. |

|||

At oral argument, the state defended its statute on two grounds: first, that states had a compelling interest in preserving a venerated [[national symbol]]; and second, that the state had a compelling interest in preventing breaches of the peace. |

|||

Grunts and howls do not inspire laws banning them, however. A person who grunts in public is looked at as being strange, but we don’t punish them for grunting instead of communicating in whole sentences. If people are antagonized by desecration of the American flag, it’s because of what they believe is being communicated by such acts. |

|||

As to the "breach of the peace" justification, however, the court found that "no disturbance of the peace actually occurred or threatened to occur because of Johnson's burning of the flag," and Texas conceded as much. The Court rejected Texas's claim that flag burning is punishable on the basis that it ''tends to incite'' breaches of the peace by citing the familiar test of ''[[Brandenburg v. Ohio]]'' that the state may only punish speech that would incite "imminent lawless action," finding that flag burning does not always pose an imminent threat of lawless action. The Court noted that Texas already punished "breaches of the peace" directly. |

|||

In a separate dissent, Justice Stevens wrote: |

|||

''' |

|||

The most contentious issue before the Court, then, was whether states possessed an interest in preserving the flag as a unique symbol of national identity and principles. Texas argued that desecration of the flag impugned its value as such a unique national symbol, and that the state possessed the power to prevent this result.''' |

|||

Anthony Kennedy wrote a short concurrence. In the concurring opinion, Kennedy stated that he fully agreed with the decision and the reasoning behind the decision. However, he also voiced his sympathy for the four dissenting Justices. |

|||

[O]ne intending to convey a message of respect for the flag by burning it in a public square might nonetheless be guilty of desecration if he knows that others - perhaps simply because they misperceive the intended message - will be seriously offended. Indeed, even if the actor knows that all possible witnesses will understand that he intends to send a message of respect, he might still be guilty of desecration if he also knows that this understanding does not lessen the offense taken by some of those witnesses. |

|||

=== Rehnquist's dissent === |

|||

This suggests that it’s permissible to regulate people’s speech based upon how others will interpret that speech. All of the laws against “desecrating” an American flag, even those which merely prohibit attaching an emblem to one, do so in the context of publicly displaying the altered flag. Doing it in private isn’t a crime; therefore, the harm to be prevented must be the “harm” of others witnessing what was done. It can’t be merely to prevent them from being offended, otherwise public discourse would be reduced to platitudes. |

|||

Brennan's opinion for the court generated two dissents. [[William H. Rehnquist]], joined by two other justices, argued that the "uniqueness" of the flag "justifies a governmental prohibition against flag burning in the way respondent Johnson did here." Rehnquist wrote, |

|||

<blockquote> |

|||

The American flag, then, throughout more than 200 years of our history, has come to be the visible symbol embodying our Nation. It does not represent the views of any particular political party, and it does not represent any particular political philosophy. The flag is not simply another "idea" or "point of view" competing for recognition in the marketplace of ideas. Millions and millions of Americans regard it with an almost mystical reverence regardless of what sort of social, political, or philosophical beliefs they may have. I cannot agree that the First Amendment invalidates the Act of [[United States Congress|Congress]], and the laws of 48 of the 50 States, which make criminal the public burning of the flag. |

|||

</blockquote> |

|||

Rehnquist also argued that flag burning is "no essential part of any exposition of ideas" but rather "the equivalent of an inarticulate grunt or roar that, it seems fair to say, is most likely to be indulged in not to express any particular idea, but to antagonize others." He goes on to say that he felt the statute in question was a reasonable restriction only on the manner in which Johnson's idea was expressed, leaving Johnson with, "a full panoply of other symbols and every conceivable form of verbal expression to express his deep disapproval of national policy." He quotes a 1984 Supreme Court decision in ''[[City Council of Los Angeles v. Taxpayers for Vincent]]'', where the majority stated that, "the First Amendment does not guarantee the right to employ every conceivable method of communication at all times and in all places." |

|||

=== Stevens' dissent === |

|||

Instead, it must be to protect others from experiencing a radically different attitude towards and interpretation of the flag. Of course, it’s unlikely that someone would be prosecuted for desecrating a flag if only one or two random people are upset — no, that will be reserved for those who upset larger numbers of witnesses. In other words, the wishes of the majority to not be confronted with something too far outside their normal expectations can limit what sorts of ideas are expressed (and in what way) by the minority. |

|||

Justice [[John Paul Stevens]], often counted as a First Amendment liberal, also wrote a dissenting opinion. Stevens, a [[World War II]] veteran, was visibly offended at oral argument by the flippancy of Johnson's counsel, [[William Kunstler]], in arguing for Johnson's right to destroy the flag. Stevens argued that the flag "is more than a proud symbol of the courage, the determination, and the gifts of nature that transformed 13 fledgling Colonies into a world power. It is a symbol of freedom, of equal opportunity, of religious tolerance, and of good will for other peoples who share our aspirations...The value of the flag as a symbol cannot be measured." Stevens concluded, therefore, that "The case has nothing to do with 'disagreeable ideas.' It involves disagreeable conduct that, in my opinion, diminishes the value of an important national asset," and that Johnson was punished only for the means by which he expressed his opinion, not the opinion itself. |

|||

This principle is completely foreign to constitutional law and even to the basic principles of liberty, as was eloquently stated the following year in the Supreme Court’s follow-up case of United States v. Eichman: |

|||

While flag desecration - like virulent ethnic and religious epithets, vulgar repudiations of the draft, and scurrilous caricatures - is deeply offensive to many, the Government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable. |

|||

If freedom of expression is to have any real substance, it must cover the freedom to express ideas that are uncomfortable, offensive, and disagreeable. That’s precisely what burning, defacing, or desecrating an American flag often does — and the same is true with defacing or desecrating other objects which are commonly revered. The government has no authority to limit people’s uses of such object to communicate only approved, moderate, and inoffensive messages. |

|||

==Subsequent developments== |

==Subsequent developments== |

||

Revision as of 12:56, 8 December 2007

| Texas v. Johnson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued March 21, 1989 Decided June 21, 1989 | |

| Full case name | Texas v. Gregory Lee Johnson |

| Citations | 491 U.S. 397 (more) 109 S. Ct. 2533; 105 L. Ed. 2d 342; 1989 U.S. LEXIS 3115; 57 U.S.L.W. 4770 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Defendant convicted, Dallas County Criminal Court; affirmed, 706 S.W.2d 120 (Tex. App. 1986); reversed and remanded for dismissal, 755 S.W.2d 92 (Tex. Crim. App. 1988); cert. granted, 488 U.S. 884 (1988) |

| Holding | |

| A statute that criminalizes the desecration of the American flag violates the First Amendment. Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Brennan, joined by Marshall, Blackmun, Scalia, Kennedy |

| Concurrence | Kennedy |

| Dissent | Rehnquist, joined by White, O'Connor |

| Dissent | Stevens |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amend. I; Tex. Penal Code § 42.11(a) | |

Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989)[1], was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that invalidated prohibitions on desecrating the American flag in force in 48 of the 50 states. Justice William Brennan wrote for a five-justice majority in holding that the defendant's act of flag burning was protected speech under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. Johnson was represented by attorneys David D. Cole and William Kunstler.

Background of the case

Greg Lee Johnson participated in a political demonstration during the Republican National Convention in Dallas, Texas, in 1984. The demonstrators were protesting the policies of the Reagan Administration and of certain companies based in Dallas. They marched through the streets, shouted slogans, and held protests outside the offices of several companies. At one point, another demonstrator handed Johnson an American flag.

When the demonstrators reached Dallas City Hall, Johnson poured kerosene on the flag and set it on fire. During the burning of the flag, demonstrators shouted "America, the red, white, and blue, we spit on you." No one was hurt, but some witnesses to the flag burning said they were extremely offended. One witness picked up the flag's burned remains and buried them in his backyard.

Johnson was charged with violating the Texas law that prohibits vandalizing respected objects. He was convicted, sentenced to one year in prison, and fined $2,000. He appealed his conviction to the Court of Appeals for the Fifth District of Texas, but he lost this appeal. He then took his case to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, which is the highest court in Texas that hears criminal cases. That court overturned his conviction, saying that the State could not punish Johnson for burning the flag because the First Amendment protects such activity as symbolic speech.

The State had said that its interests were more important than Johnson's symbolic speech rights because it wanted to preserve the flag as a symbol of national unity, and because it wanted to maintain order. The court said neither of these state interests could be used to justify Johnson's conviction.

The court said, "Recognizing that the right to differ is the centerpiece of our First Amendment freedoms, a government cannot mandate by fiat a feeling of unity in its citizens. Therefore that very same government cannot carve out a symbol of unity and prescribe a set of approved messages to be associated with that symbol . . ." The court also concluded that the flag burning in this case did not cause or threaten to cause a breach of the peace.

The State of Texas asked the Supreme Court of the United States to hear the case. In 1989, the Court handed down its decision.

The Supreme Court's decision

The opinion of the court came down as a controversial 5-4 decision, with the majority opinion written by the elderly William J. Brennan, Jr. in his penultimate term on the Court. The question the Supreme Court had to answer was: "Is the desecration of an American flag, by burning or otherwise, a form of speech that is protected under the First Amendment?".

In determining this, the court first considered the question of whether the First Amendment reached non-speech acts, since Johnson was convicted of flag desecration rather than verbal communication, and, if so, whether Johnson's burning of the flag constituted expressive conduct, which would permit him to invoke the First Amendment in challenging his conviction.

The First Amendment literally forbids the abridgment only of "speech", but the court reiterated their long recognition that its protection does not end at the spoken or written word. This was an uncontroversial conclusion in light of cases such as Stromberg v. California (display of a red flag as speech) and Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (wearing of a black armband as speech).

The court rejected "the view that an apparently limitless variety of conduct can be labeled 'speech' whenever the person engaging in the conduct intends thereby to express an idea", but acknowledged that conduct may be "sufficiently imbued with elements of communication to fall within the scope of the First and Fourteenth Amendments". In deciding whether particular conduct possesses sufficient communicative elements to bring the First Amendment into play, the court asked whether "an intent to convey a particularized message was present, and [whether] the likelihood was great that the message would be understood by those who viewed it."

The court found that, "Under the circumstances, Johnson's burning of the flag constituted expressive conduct, permitting him to invoke the First Amendment... Occurring as it did at the end of a demonstration coinciding with the Republican National Convention, the expressive, overtly political nature of the conduct was both intentional and overwhelmingly apparent." The court concluded that, while "the government generally has a freer hand in restricting expressive conduct than it has in restricting the written or spoken word," it may not "proscribe particular conduct because it has expressive elements."

Texas had conceded, however, that Johnson's conduct was expressive in nature. Thus, the key question considered by the Court was "whether Texas has asserted an interest in support of Johnson's conviction that is unrelated to the suppression of expression."

At oral argument, the state defended its statute on two grounds: first, that states had a compelling interest in preserving a venerated national symbol; and second, that the state had a compelling interest in preventing breaches of the peace.

As to the "breach of the peace" justification, however, the court found that "no disturbance of the peace actually occurred or threatened to occur because of Johnson's burning of the flag," and Texas conceded as much. The Court rejected Texas's claim that flag burning is punishable on the basis that it tends to incite breaches of the peace by citing the familiar test of Brandenburg v. Ohio that the state may only punish speech that would incite "imminent lawless action," finding that flag burning does not always pose an imminent threat of lawless action. The Court noted that Texas already punished "breaches of the peace" directly. The most contentious issue before the Court, then, was whether states possessed an interest in preserving the flag as a unique symbol of national identity and principles. Texas argued that desecration of the flag impugned its value as such a unique national symbol, and that the state possessed the power to prevent this result.

Anthony Kennedy wrote a short concurrence. In the concurring opinion, Kennedy stated that he fully agreed with the decision and the reasoning behind the decision. However, he also voiced his sympathy for the four dissenting Justices.

Rehnquist's dissent

Brennan's opinion for the court generated two dissents. William H. Rehnquist, joined by two other justices, argued that the "uniqueness" of the flag "justifies a governmental prohibition against flag burning in the way respondent Johnson did here." Rehnquist wrote,

The American flag, then, throughout more than 200 years of our history, has come to be the visible symbol embodying our Nation. It does not represent the views of any particular political party, and it does not represent any particular political philosophy. The flag is not simply another "idea" or "point of view" competing for recognition in the marketplace of ideas. Millions and millions of Americans regard it with an almost mystical reverence regardless of what sort of social, political, or philosophical beliefs they may have. I cannot agree that the First Amendment invalidates the Act of Congress, and the laws of 48 of the 50 States, which make criminal the public burning of the flag.

Rehnquist also argued that flag burning is "no essential part of any exposition of ideas" but rather "the equivalent of an inarticulate grunt or roar that, it seems fair to say, is most likely to be indulged in not to express any particular idea, but to antagonize others." He goes on to say that he felt the statute in question was a reasonable restriction only on the manner in which Johnson's idea was expressed, leaving Johnson with, "a full panoply of other symbols and every conceivable form of verbal expression to express his deep disapproval of national policy." He quotes a 1984 Supreme Court decision in City Council of Los Angeles v. Taxpayers for Vincent, where the majority stated that, "the First Amendment does not guarantee the right to employ every conceivable method of communication at all times and in all places."

Stevens' dissent

Justice John Paul Stevens, often counted as a First Amendment liberal, also wrote a dissenting opinion. Stevens, a World War II veteran, was visibly offended at oral argument by the flippancy of Johnson's counsel, William Kunstler, in arguing for Johnson's right to destroy the flag. Stevens argued that the flag "is more than a proud symbol of the courage, the determination, and the gifts of nature that transformed 13 fledgling Colonies into a world power. It is a symbol of freedom, of equal opportunity, of religious tolerance, and of good will for other peoples who share our aspirations...The value of the flag as a symbol cannot be measured." Stevens concluded, therefore, that "The case has nothing to do with 'disagreeable ideas.' It involves disagreeable conduct that, in my opinion, diminishes the value of an important national asset," and that Johnson was punished only for the means by which he expressed his opinion, not the opinion itself.

Subsequent developments

The Court's decision, which invalidated the laws in force in 48 of the 50 states, set off a wave of protest that continues to this day, as many Americans are deeply outraged by desecration of the flag. Subsequent to Texas v. Johnson, proposals were introduced year after year in Congress to amend the Constitution to allow the federal government and states to prohibit flag burning. On several occasions this amendment came close to passage, obtaining the requisite two-thirds majority in the House, only to fail in the Senate.

Congress did, however, pass a statute, the 1989 Flag Protection Act, making it a federal crime to desecrate the flag. In the case of United States v. Eichman, 496 U.S. 310 (1990)[2], that law was struck down by the same five person majority of justices as in Johnson (in an opinion also written by Justice Brennan).

Since then, Congress has considered the Flag Desecration Amendment several times. The amendment usually passes the House of Representatives, but has always been defeated in the Senate. The most recent attempt occurred when S.J.Res.12[3] failed by one vote on June 27, 2006.

Notes

External links

- Text of the decision

- Audio recording of oral arguments

- First Amendment Library entry on Texas v. Johnson

- Thoughts on Flag Burning and other statements by Edward Hasbrouck and Joey Johnson

- Texas v. Johnson (1989) from LandmarkCases.org