Oracle bone: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 196876691 by 75.16.27.70 (talk) |

|||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

==Discovery== |

==Discovery== |

||

The |

The Shang-dynasty oracle bones were unearthed in 19th-century China, and were sold as ''dragon bones'' (lóng gǔ 龍骨) in the [[Chinese herbology|traditional Chinese medicine]] markets, used either whole or crushed for the healing of various ailments, including knife wounds. They were not recognized as bearing ancient Chinese writing until 1899, when they fell into the hands of two scholars, Wáng Yìróng (王懿榮) (1845-1900), who according to one legend was sick with [[malaria]], and his friend Liú È (刘鶚) (1857-1909), who was visiting and helped examine his medicine. They discovered, before it was ground into powder, that it bore strange glyphs, which they recognized as ancient writing. Word spread among collectors of antiquities, and the market for oracle bones exploded. Decades of uncontrolled digs followed, and many of these pieces eventually entered collections in Europe, the US and Japan. Sometimes they would use human or caveman bones. |

||

Upon the establishment of the Institute of History and Philology at the [[Academia Sinica]] in 1928, the source of the oracle bones was traced back to modern Xiaotun (小屯) village near [[Anyang]] in [[Henan]] Province. Official archaeological excavations in 1928-1937 led by Li Ji (李济) discovered 20,000 oracle bone pieces, which now form the bulk of the Academia Sinica's collection in [[Taiwan]]. The inscriptions on the oracle bones, once deciphered, turned out to be the records of the divinations performed for or by the royal household. These together proved beyond a doubt for the first time the existence of the |

Upon the establishment of the Institute of History and Philology at the [[Academia Sinica]] in 1928, the source of the oracle bones was traced back to modern Xiaotun (小屯) village near [[Anyang]] in [[Henan]] Province. Official archaeological excavations in 1928-1937 led by Li Ji (李济) discovered 20,000 oracle bone pieces, which now form the bulk of the Academia Sinica's collection in [[Taiwan]]. The inscriptions on the oracle bones, once deciphered, turned out to be the records of the divinations performed for or by the royal household. These together proved beyond a doubt for the first time the existence of the Shang Dynasty and the location of its last capital. The writing on them is also the earliest significant corpus of [[Written Chinese|Chinese writing]], and is essential for the study of Chinese [[etymology]], as it is directly ancestral to the modern script. |

||

==Usage== |

==Usage== |

||

Revision as of 06:26, 10 March 2008

Template:Contains Chinese text

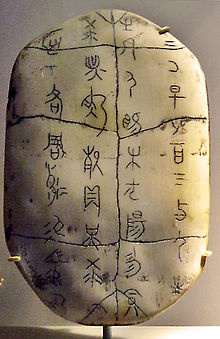

Oracle bones (甲骨文 pinyin: jiǎgǔpiàn) are pieces of bone or turtle shell used in royal divination from the mid Shang to early Zhou dynasties in ancient China, and often bearing written inscriptions in what is called oracle bone script.

Discovery

The Shang-dynasty oracle bones were unearthed in 19th-century China, and were sold as dragon bones (lóng gǔ 龍骨) in the traditional Chinese medicine markets, used either whole or crushed for the healing of various ailments, including knife wounds. They were not recognized as bearing ancient Chinese writing until 1899, when they fell into the hands of two scholars, Wáng Yìróng (王懿榮) (1845-1900), who according to one legend was sick with malaria, and his friend Liú È (刘鶚) (1857-1909), who was visiting and helped examine his medicine. They discovered, before it was ground into powder, that it bore strange glyphs, which they recognized as ancient writing. Word spread among collectors of antiquities, and the market for oracle bones exploded. Decades of uncontrolled digs followed, and many of these pieces eventually entered collections in Europe, the US and Japan. Sometimes they would use human or caveman bones.

Upon the establishment of the Institute of History and Philology at the Academia Sinica in 1928, the source of the oracle bones was traced back to modern Xiaotun (小屯) village near Anyang in Henan Province. Official archaeological excavations in 1928-1937 led by Li Ji (李济) discovered 20,000 oracle bone pieces, which now form the bulk of the Academia Sinica's collection in Taiwan. The inscriptions on the oracle bones, once deciphered, turned out to be the records of the divinations performed for or by the royal household. These together proved beyond a doubt for the first time the existence of the Shang Dynasty and the location of its last capital. The writing on them is also the earliest significant corpus of Chinese writing, and is essential for the study of Chinese etymology, as it is directly ancestral to the modern script.

Usage

The oracle bones are mostly ox scapulae (shoulder blades) and turtle shells, although some other animal bones, and even the skulls of deer and humans were sometimes used. Both the dorsal or back shell (carapace) and ventral or belly shell (plastron) of turtles were used, and since these are actually a bony material, the term "oracle bones" is applied to them as well.

The bones or shells were prepared for use by sawing and smoothing them, and notations were often made on them recording their provenance (e.g. tribute of how many shells from where and on what date). These notations were generally made on the back of the shell's bridge (called bridge notations), the lower carapace or the xiphiplastron (tail edge). Scapula notations were near the socket or a lower edge. Some of these were not carved after being written with a brush, proving (along with other evidence) the use of the writing brush in Shang times (Keightley, 1978).

Pits or hollows were then drilled or chiseled partway through the bone, and a topic was divined upon during a ceremony, during which a heat source was applied into one of the pits until the bone cracked at that point. Due to the shape of the pit, the front side of the bone cracked in a rough 卜 shape. The character 卜 (pinyin: bǔ; Old Chinese: *puk; "to divine") may be a pictogram of such a crack; the reading of the character may also be an onomatopoeia for the cracking. A number of cracks were typically made in one session, and the diviner in charge of the ceremony, who was sometimes the Shang king himself, then read the cracks to learn the answer to the divination. How exactly the cracks were interpreted is not known. The topic of divination was raised multiple times, and often in different ways, such as in the negative, or by changing the date being divined about. One oracle bone might be used for one session, or for many, and one session could be recorded on a number of bones. The question was nearly always posed in a yes or no format, so that the divined answer would be either "auspicious" or "inauspicious."

The inscriptions are fairly formulaic, generally "(on) AB date (using the sexagenary cycle), divination was performed by person C regarding (topic)". Additional inscriptions include notations as to provenance of the bones or shells, numbering of the cracks made, annotations as to their auspiciousness, proclamations as to the conclusion of the divination session, and sometimes verifications of whether a future event indeed came to pass. The topics, and sometimes the answers, are then thought to have been brush-written on the oracle bones or accompanying documents, later to be carved in a workshop. A few of the oracle bones found still bear their brush-written records, without carving, while some have been found partially carved.

This kind of divination, involving the application of heat or fire, is called pyromancy; when applied to a scapula or plastron, it is also termed scapulimancy or plastromancy respectively. The divination questions or topics were often directed at ancestors, whom the ancient Chinese revered and worshiped, as well as natural powers and Dì (帝), the highest god in the Shang society. A wide variety of topics were asked, essentially anything of concern to the royal house of Shang, from illness, birth and death, to weather, warfare, agriculture, tribute and so on. One of the most common topics was whether performing rituals in a certain manner would be satisfactory.

Evidence of pyromancy and scapulomancy in ancient China extends back to the 4th millennium BCE, with finds from Liaoning, but these were not inscribed. Evidence of scapulomancy with inscriptions may date back to the pre-Shang site of Erligang (二里崗) in Zhengzhou, Henan, where burned scapula of oxen, sheep and pigs were found, and one bone fragment from a pre-Shang layer is inscribed with a graph (ㄓ) corresponding to Shang script.

However, significant quantities of inscribed oracle bones date only to the middle of the Shang Dynasty, probably in the reign of Pangeng, around 1350 BCE when the Shang capital was moved to Yin at modern Anyang. The vast majority date to around the 13th to 11th centuries BCE, or late Shāng. The oracle bones are not the earliest writing in China. A few Shāng bronzes with extremely short inscriptions predate them. However, the oracle bones are considered the earliest significant body of writing, due to the length of the inscriptions, the vast amount of vocabulary (very roughly 4000 graphs), and the sheer quantity of pieces found (now well over 100,000). There are also graphs found inscribed or brush-written on Neolithic period pottery shards, but whether or not these constitute writing or are ancestral to the Shang writing system is currently a matter of great academic controversy.

After the Zhou conquest, the Shang practices of bronze casting, pyromancy and writing continued. Oracle bones found in the 1970s have been dated to the Zhou dynasty, with some dating to the spring and autumn period. However, very few of those were inscribed. It is thought that other methods of divination supplanted pyromancy, such as numerological divination using milfoil (yarrow) in connection with the hexagrams of the I Ching.

References

- Keightley, David N. (1978). Sources of Shang History: The Oracle-Bone Inscriptions of Bronze Age China. University of California Press, Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-02969-0; Paperback 2nd edition (1985) ISBN 0-520-05455-5.

- Keightley, David N. (2000). The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China (ca. 1200 – 1045 B.C.). China Research Monograph 53, Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 1-55729-070-9.

- Qiu Xigui (裘錫圭) (2000). Chinese Writing. Translation of 文字学概要 by Gilbert L. Mattos and Jerry Norman. Early China Special Monograph Series No. 4. The Society for the Study of Early China and the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 1-55729-071-7.

- Xu Yahui (許雅惠 Hsu Ya-huei) (2002). Ancient Chinese Writing, Oracle Bone Inscriptions from the Ruins of Yin. Illustrated guide to the Special Exhibition of Oracle Bone Inscriptions from the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica. English translation by Mark Caltonhill and Jeff Moser. National Palace Museum, Taipei. Govt. Publ. No. 1009100250.