Islamic world contributions to Medieval Europe: Difference between revisions

Alvestrand (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 72.220.185.237 (talk) to last version by Yobmod |

mentioned the time period of the quote |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

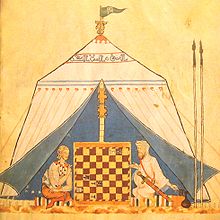

[[Image:ChristianAndMuslimPlayingChess.JPG|thumb|Christian and Muslim playing [[chess]] in the [[Levant]]. The game of chess originated in [[India]], but was transmitted to Europe by the Islamic world.<ref name="Lebedel1">Lebedel, p.109</ref>]] |

[[Image:ChristianAndMuslimPlayingChess.JPG|thumb|Christian and Muslim playing [[chess]] in the [[Levant]]. The game of chess originated in [[India]], but was transmitted to Europe by the Islamic world.<ref name="Lebedel1">Lebedel, p.109</ref>]] |

||

The '''Islamic contributions to Medieval Europe''' were important and numerous. These contributions affected such varied areas as [[Islamic art|arts]], [[Islamic architecture|architecture]], [[Islamic science|sciences]], techniques, [[Islamic medicine|medicine]], [[Muslim Agricultural Revolution|foods]], [[Islamic music|music]], [[Influence of Arabic on other languages|vocabulary]], [[Madrasah|education]], [[Arabic literature|literature]], [[Sharia|law]], [[Early Islamic philosophy|philosophy]] and [[Inventions in the Islamic world|technology]]. From the 10th to the 13th century, Europe literally absorbed vast quantities of knowledge from the [[Islamic Golden Age|Islamic civilization]].<ref name="Lebedel1"/> |

The '''Islamic contributions to Medieval Europe''' were important and numerous. These contributions affected such varied areas as [[Islamic art|arts]], [[Islamic architecture|architecture]], [[Islamic science|sciences]], techniques, [[Islamic medicine|medicine]], [[Muslim Agricultural Revolution|foods]], [[Islamic music|music]], [[Influence of Arabic on other languages|vocabulary]], [[Madrasah|education]], [[Arabic literature|literature]], [[Sharia|law]], [[Early Islamic philosophy|philosophy]] and [[Inventions in the Islamic world|technology]]. From the 10th to the 13th century, Europe literally absorbed vast quantities of knowledge from the [[Islamic Golden Age|Islamic civilization]].<ref name="Lebedel1"/> Since the early 20th century, there had been a "growing number of scholars who recognize that the influence of the [[Muslim world|Muslim civilization]] as a whole on [[Middle Ages|medieval Europe]] was enormously greater and was exerted in far more fields, scientific, philosophical, [[Kalam|theological]], literary, [[Aesthetics|esthetic]], than has hitherto been recognized."<ref>{{citation|first=D. B.|last=Macdonald|title=Reviewed work(s): ''Historical Facts for the Arabian Musical Influence'' by Henry George Farmer|[[Isis (journal)|Isis]]|volume=15|issue=2|date=April 1931|pages=370-372 [371]}}</ref> This had considerable effects on the development of [[Western civilization]], leading in many ways to the achievement of the [[Renaissance]].<ref>”Without contacts with the arab culture, Renaissance could probably not have happened in the 15th and 16th century”, Lebedel, p. 109</ref> |

||

{{TOClimit|limit=2}} |

{{TOClimit|limit=2}} |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

{{see|Latin translations of the 12th century|Arab-Norman culture}} |

{{see|Latin translations of the 12th century|Arab-Norman culture}} |

||

[[Image:TabulaRogeriana.jpg|thumb|The [[Tabula Rogeriana]], drawn by [[Al-Idrisi]] for [[Roger II of Sicily]] in 1154, one of the most advanced [[ancient world maps]].]] |

[[Image:TabulaRogeriana.jpg|thumb|The [[Tabula Rogeriana]], drawn by [[Al-Idrisi]] for [[Roger II of Sicily]] in 1154, one of the most advanced [[ancient world maps]].]] |

||

The points of contact between Europe and Islamic lands were multiple during the Middle Ages. The main points of transmission of Islamic knowledge to Europe were in [[Sicilia]], and in [[Al-Andalus|Islamic Spain]], particularly in [[Toledo, Spain|Toledo]] (with [[ |

The points of contact between Europe and Islamic lands were multiple during the Middle Ages. The main points of transmission of Islamic knowledge to Europe were in [[Sicilia]], and in [[Al-Andalus|Islamic Spain]], particularly in [[Toledo, Spain|Toledo]] (with [[Gerar |

||

The [[Crusades]] also intensified exchanges between Europe and the [[Levant]], with Italian City Republics taking a great role in these exchanges. In the Levant, such cities as [[Antioch]], Arab and Latin cultures intermixed intensively.<ref>Lebedel, p.109-111</ref> |

|||

==Classical knowledge== |

|||

Following the fall of the [[Roman Empire]] and the dawn of the [[Middle Ages]], many texts from [[Classical Antiquity]] had been lost to the Europeans. In the [[Middle East]] however, many of these Greek texts (such as [[Aristotle]]) were translated from [[Greek language|Greek]] into [[Syriac]] during the 6th and the 7th century by [[Nestorian]], [[Melkites]] or [[Jacobite]] monks living in [[Palestine]], or by Greek exiles from [[Athens]] or [[Edessa]] who visited Islamic Universities. Many of these texts however were then kept, translated, and developed upon by the Islamic world, especially in centers of learning such as [[Baghdad]], where a “[[House of Wisdom]]”, with thousands of manuscripts existed as soon as 832. These texts were translated again into European languages during the Middle Ages.<ref name="Lebedel1"/> Eastern Christians played an important role in exploiting this knowledge, especially through the Christian Aristotelician School of Baghdad in the 11th and 12th centuries. |

|||

These texts were translated back into Latin in multiple ways. The main points of transmission of Islamic knowledge to Europe were in [[Sicilia]], and in [[Toledo, Spain|Toledo]], [[Spain]] (with [[Gerard of Cremone]], 1114-1187). [[Burgondio of Pise]] (died in 1193), who discovered in Antioch lost texts of [[Aristotle]], translated them into Latin. |

|||

==Islamic sciences== |

|||

{{see|Latin translations of the 12th century|Islamic science}} |

|||

[[Image:ChirurgicalOperation15thCentury.JPG|thumb|Chirurgical operation, 15th century Turkish manuscript.]] |

|||

Islam was not, however, a simple re-transmitter of knowledge from antiquity. It also developed its own sciences, such as [[algebra]], [[Alchemy and chemistry in Islam|chemistry]], [[geology]], [[spherical trigonometry]], etc. which were later also transmitted to the West.<ref>Lebedel, p. 109</ref><ref>[[Fielding H. Garrison]], ''An Introduction to the History of Medicine: with Medical Chronology, Suggestions for Study and Biblographic Data'', p. 86</ref> |

|||

Stefan of Pise translated into Latin around 1127 an Arab manual of medical theory. The method of [[algorism]] for performing arithmetic with Indian-[[Arabic numerals]] was developed by [[al-Khwarizmi]] (hence the word “[[Algorithm]]”) in the 9th century, and introduced in Europe by [[Leonardo Fibonacci]] (1170-1250).<ref>Lebedel, p.111</ref> A translation of the ''[[The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing|Algebra]]'' by al-Kharizmi is known as early as 1145, by a certain [[Robert of Chester]]. [[Ibn al-Haytham]] (Alhazen, 980-1037) compiled treaties on optical sciences, which were used as references by [[Newton]] and [[Descartes]]. Medical sciences were also highly developed in Islam as testified by the Crusaders, who relied on Arab doctors on numerous occasions. [[Joinville]] reports he was saved in 1250 by a “[[Saracen]]” doctor.<ref>Lebedel, p.112</ref> |

|||

Contributing to the growth of European science was the major search by European scholars for new learning which they could only find among Muslims, especially in [[Al-Andalus|Islamic Spain]] and [[History of Islam in southern Italy|Sicily]]. These scholars translated new scientific and philosophical texts from [[Arabic language|Arabic]] into [[Latin]]. |

|||

One of the most productive translators in Spain was [[Gerard of Cremona]], who translated 87 books from Arabic to Latin,<ref name=Zaimeche/> |

|||

including [[Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī]]'s ''[[The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing|On Algebra and Almucabala]]'', [[Jabir ibn Aflah]]'s ''Elementa astronomica'',<ref name=Katz/> |

|||

[[al-Kindi]]'s ''On Optics'', [[Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Kathīr al-Farghānī]]'s ''On Elements of Astronomy on the Celestial Motions'', [[al-Farabi]]'s ''On the Classification of the Sciences'',<ref>For a list of Gerard of Cremona's translations see: Edward Grant (1974) ''A Source Book in Medieval Science'', (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Pr.), pp. 35-8 or Charles Burnett, "The Coherence of the Arabic-Latin Translation Program in Toledo in the Twelfth Century," ''Science in Context'', 14 (2001): at 249-288, at pp. 275-281.</ref> |

|||

the [[Alchemy and chemistry in Islam|chemical]] and [[Islamic medicine|medical]] works of [[Rhazes]],<ref name=Bieber/> |

|||

the works of [[Thabit ibn Qurra]] and [[Hunayn ibn Ishaq]],<ref>D. Campbell, ''Arabian Medicine and Its Influence on the Middle Ages'', p. 6.</ref> |

|||

and the works of [[Arzachel]], [[Jabir ibn Aflah]], the [[Banū Mūsā]], [[Abū Kāmil Shujā ibn Aslam]], [[Abu al-Qasim]], and [[Ibn al-Haytham]] (including the ''[[Book of Optics]]'').<ref name=Zaimeche/> |

|||

===Alchemy and chemistry=== |

|||

{{see also|Alchemy and chemistry in Islam}} |

|||

The [[Chemistry|chemical]] and [[Alchemy|alchemical]] works of [[Geber]] (Jabir ibn Hayyan) were translated into Latin around the 12th century and became standard texts for European alchemists.<ref name=Bieber/> These include the ''Kitab al-Kimya'' (titled ''Book of the Composition of Alchemy'' in Europe), translated by [[Robert of Chester]] (1144); and the ''Kitab al-Sab'een'', translated by [[Gerard of Cremona]] (before 1187). |

|||

[[Marcelin Berthelot]] translated some of Jabir's books under the fanciful titles ''Book of the Kingdom'', ''Book of the Balances'', and ''Book of Eastern Mercury''. Several technical [[Influence of Arabic on other languages|Arabic terms]] introduced by Jabir, such as ''[[alkali]]'', have found their way into various European languages and have become part of scientific vocabulary. |

|||

The chemical and alchemical works of [[Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi]] (Rhazes) were also translated into Latin around the 12th century.<ref name=Bieber/> |

|||

===Astronomy and mathematics=== |

|||

[[Image:Talhoffer Thott 140r.jpg|thumb|A German manuscript page teaching use of [[Arabic numerals]] ([[Hans Talhoffer|Talhoffer]] Thott, 1459).]] |

|||

{{see also|Islamic astronomy|Islamic mathematics}} |

|||

Arabic astronomical and mathematical works translated into Latin during the 12th century include the works of [[Muhammad ibn Jābir al-Harrānī al-Battānī]] and [[Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī]], including ''[[The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing]]'', one of the founding texts of [[algebra]];<ref name=Katz/> and [[Muhammad al-Fazari]]'s ''Great Sindhind'' (based on the ''[[Surya Siddhanta]]'' and the works of [[Brahmagupta]]).<ref>G. G. Joseph, ''The Crest of the Peacock'', p. 306</ref> |

|||

[[Al-Khazini]]'s ''[[Zij]] as-Sanjari'' (1115-1116) was translated into [[Greek language|Greek]] by [[Gregory Choniades]] in the 13th century and was studied in the [[Byzantine Empire]].<ref>David Pingree (1964), "Gregory Chioniades and Palaeologan Astronomy", ''Dumbarton Oaks Papers'' '''18''', p. 135-160.</ref> The astronomical corrections to the [[Ptolemaic model]] made by [[al-Battani]] and [[Averroes]] and the non-Ptolemaic models produced by [[Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi]] (Urdi lemma), [[Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī]] ([[Tusi-couple]]) and [[Ibn al-Shatir]] were later adapted into the [[Copernican heliocentrism|Copernican heliocentric]] model. [[Al-Kindi]]'s (Alkindus) law of [[Terrestrial planet|terrestrial]] [[Gravitation|gravity]] influenced [[Robert Hooke]]'s law of [[Astronomical object|celestial]] gravity, which in turn inspired [[Newton's law of universal gravitation]]. [[Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī]]'s ''Ta'rikh al-Hind'' and ''Kitab al-qanun al-Mas’udi'' were translated into Latin as ''Indica'' and ''Canon Mas’udicus'' respectively. |

|||

[[Fibonacci]] presented the first complete European account of the [[Hindu-Arabic numeral system]] from [[Arabic numerals|Arabic sources]] in his ''[[Liber Abaci]]'' (1202).<ref name=Bieber>Jerome B. Bieber. [http://inst.santafe.cc.fl.us/~jbieber/HS/trans2.htm Medieval Translation Table 2: Arabic Sources], [[Santa Fe Community College (Florida)|Santa Fe Community College]].</ref> [[Al-Jayyani]]'s ''The book of unknown arcs of a sphere'', the first treatise on [[spherical trigonometry]], had a "strong influence on European mathematics", and his "definition of [[ratio]]s as numbers" and "method of solving a spherical triangle when all sides are unknown" are likely to have influenced [[Regiomontanus]].<ref>{{MacTutor|id=Al-Jayyani|title=Abu Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Muadh Al-Jayyani}}</ref> |

|||

Translations of the algebraic and geometrical works of [[Ibn al-Haytham]], [[Omar Khayyám]] and [[Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī]] were later influential in the development of [[non-Euclidean geometry]] in Europe from the 17th century.<ref>D. S. Kasir (1931). ''The Algebra of Omar Khayyam'', p. 6-7. [[Columbia University Press|Teacher's College Press]], [[Columbia University]], [[New York]].</ref><ref>Boris A. Rosenfeld and Adolf P. Youschkevitch (1996), "Geometry", p. 469, in {{Harv|Morelon|Rashed|1996|pp=447-494}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Al-RaziInGerardusCremonensis1250.JPG|thumb|European depiction of the Persian doctor [[Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi|al-Razi]], in [[Gerard of Cremona]]'s ''Receuil des traites de medecine'' (1250-1260). Gerard de Cremona translated numerous works by Arabic scholars, such as al-Razi's, but also those of [[Avicenna|Ibn Sina]].<ref>"Inventions et decouvertes au Moyen-Age", Samuel Sadaune, p.44</ref>]] |

|||

===Medicine=== |

|||

{{see also|Islamic medicine}} |

|||

[[Hospital]]s began as [[Bimaristan]]s in the Islamic world and later spread to Europe during the [[Crusades]], inspired by the hospitals in the Middle East. The first hospital in [[Paris]], Les Quinze-vingt, was founded by [[Louis IX of France|Louis IX]] after his return from the Crusade between 1254-1260.<ref name=Sarton>[[George Sarton]], ''Introduction to the History of Science''.<br>([[cf.]] Dr. A. Zahoor and Dr. Z. Haq (1997), [http://www.cyberistan.org/islamic/Introl1.html Quotations From Famous Historians of Science], Cyberistan.</ref> One of the most important medical works to be translated was [[Avicenna]]'s ''[[The Canon of Medicine]]'' (1025), which was translated into Latin and then disseminated in manuscript and printed form throughout Europe. It remained a standard medical textbook in Europe up until the early modern period, and during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries alone, ''The Canon of Medicine'' was published more than thirty-five times.<ref name=NLM>[[National Library of Medicine]] digital archives</ref> It introduced the contagious nature of [[infectious disease]]s, the method of [[quarantine]], [[experimental medicine]], and [[clinical trial]]s.<ref name=Tschanz>David W. Tschanz, MSPH, PhD (August 2003). "Arab Roots of European Medicine", ''Heart Views'' '''4''' (2).</ref> He also wrote ''[[The Book of Healing]]'', a more general encyclopedia of science and philosophy, which became another popular textbook in Europe. [[Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi]]'s ''Comprehensive Book of Medicine'', with its introduction of [[measles]] and [[smallpox]], was also influential in Europe. [[Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi]]'s ''[[Al-Tasrif|Kitab al-Tasrif]]'' was also translated to Latin and used in European [[medical school]]s for centuries.<ref name=Campbell-3>D. Campbell, ''Arabian Medicine and Its Influence on the Middle Ages'', p. 3.</ref><ref name=Zaimeche/> |

|||

[[Ibn al-Nafis]]' ''Commentary on Compound Drugs'' was translated into Latin by Andrea Alpago (d. 1522), who may have also translated Ibn al-Nafis' ''Commentary on Anatomy in the Canon of Avicenna'', which first described [[pulmonary circulation]] and [[coronary circulation]], and which may have had an influence on [[Michael Servetus]], [[Realdo Colombo]] and [[William Harvey]].<ref>[http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/arabic/mon4.html Anatomy and Physiology], Islamic Medical Manuscripts, [[United States National Library of Medicine]].</ref> |

|||

===Physics=== |

|||

{{see also|Islamic physics}} |

|||

One of the most important scientific works to be translated was [[Ibn al-Haytham]]'s ''[[Book of Optics]]'' (1021), which initiated a [[Scientific revolution|revolution]] in [[optics]]<ref name=Hogendijk>{{citation|last1=Sabra|first1=A. I.|author1-link=A. I. Sabra|last2=Hogendijk|first2=J. P.|year=2003|title=The Enterprise of Science in Islam: New Perspectives|pages=85-118|publisher=[[MIT Press]]|isbn=0262194821}}</ref> and [[visual perception]],<ref name=Ragep>{{Citation |last=Hatfield |first=Gary |contribution=Was the Scientific Revolution Really a Revolution in Science? |editor1-last=Ragep |editor1-first=F. J. |editor2-last=Ragep |editor2-first=Sally P. |editor3-last=Livesey |editor3-first=Steven John |year=1996 |title=Tradition, Transmission, Transformation: Proceedings of Two Conferences on Pre-modern Science held at the University of Oklahoma |page=500 |publisher=[[Brill Publishers]] |isbn=9004091262}}</ref> and introduced the earliest [[experiment]]al [[scientific method]],<ref name=Gorini>{{citation |last=Gorini |first=Rosanna |year=2003 |title=Al-Haytham the Man of Experience: First Steps in the Science of Vision |journal=Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine |publisher=Institute of Neurosciences, Laboratory of Psychobiology and Psychopharmacology, [[Rome]], [[Italy]]}}: {{quote|"According to the majority of the historians al-Haytham was the pioneer of the modern scientific method. With his book he changed the meaning of the term optics and established experiments as the norm of proof in the field. His investigations are based not on abstract theories, but on experimental evidences and his experiments were systematic and repeatable."}}</ref> for which Ibn al-Haytham is considered the "father of modern optics"<ref name=Verma>R. L. Verma, "Al-Hazen: father of modern optics", ''Al-Arabi'', 8 (1969): 12-13</ref> and founder of [[experimental physics]].<ref name=Thiele>{{citation|first=Rüdiger|last=Thiele|year=2005|title=In Memoriam: Matthias Schramm, 1928–2005|journal=Historia Mathematica|volume=32|issue=3|date=August 2005|pages=271-274}}</ref><ref>{{citation|first=Rüdiger|last=Thiele|year=2005|title=In Memoriam: Matthias Schramm|journal=Arabic Sciences and Philosophy|publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]]|volume=15|pages=329–331}}</ref> The ''Book of Optics'' laid the foundations for modern optics,<ref name=Verma/> the [[scientific method]],<ref name=Gorini/> [[experimental physics]]<ref name=Thiele/> and [[experimental psychology]],<ref name=Khaleefa>Omar Khaleefa (Summer 1999). "Who Is the Founder of Psychophysics and Experimental Psychology?", ''American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences'' '''16''' (2).</ref> for which it has been ranked alongside [[Isaac Newton]]'s ''[[Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica]]'' as one of the most influential books in the [[history of physics]].<ref name=Gomati>H. Salih, M. Al-Amri, M. El Gomati (2005). "[http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001412/141236E.pdf The Miracle of Light]", ''A World of Science'' '''3''' (3), [[UNESCO]]</ref> The [[Latin translations of the 12th century|Latin translation]] of the ''Book of Optics'' influenced the works of many later European scientists, such as [[Robert Grosseteste]], [[Roger Bacon]], [[John Peckham]], [[Witelo]], [[William of Ockham]], [[Leonardo da Vinci]], [[Francis Bacon]], [[René Descartes]], [[Johannes Kepler]], [[Galileo Galilei]], [[Isaac Newton]], and others.<ref name=Marshall>{{citation|title=Nicole Oresme on the Nature, Reflection, and Speed of Light|first=Peter|last=Marshall|journal=[[Isis (journal)|Isis]]|volume=72|issue=3|date=September 1981|pages=357-374 [367-74]}}</ref><ref name=Powers>Richard Powers ([[University of Illinois]]), [http://online.physics.uiuc.edu/courses/phys199epp/fall06/Powers-NYTimes.pdf Best Idea; Eyes Wide Open], ''[[New York Times]]'', April 18, 1999.</ref> The ''Book of Optics'' also laid the foundations for a variety of Western optical technologies, such as [[Glasses|eyeglasses]],<ref name=Kriss>{{citation|last1=Kriss|first1=Timothy C.|last2=Kriss|first2=Vesna Martich|title=History of the Operating Microscope: From Magnifying Glass to Microneurosurgery|journal=Neurosurgery|volume=42|issue=4|pages=899-907|date=April 1998}}</ref> the [[camera]],<ref name=Wade>Nicholas J. Wade, Stanley Finger (2001), "The eye as an optical instrument: from camera obscura to Helmholtz's perspective", ''Perception'' '''30''' (10): 1157-77</ref> the [[telescope]] and [[microscope]], [[microscopy]], [[retina]]l [[surgery]], and [[robot]]ic vision.<ref name=Powers/> The book also influenced other aspects of European culture. In [[religion]], for example, [[John Wycliffe]], the intellectual progenitor of the [[Protestant Reformation]], referred to Alhazen in discussing the seven deadly [[sin]]s in terms of the distortions in the seven types of [[mirror]]s analyzed in ''De aspectibus''. In [[literature]], Alhazen's ''Book of Optics'' is praised in [[Guillaume de Lorris]]' ''[[Roman de la Rose]]'' and [[Geoffrey Chaucer]]'s ''[[The Canterbury Tales]]''. In [[art]] in particular, the ''Book of Optics'' laid the foundations for the [[Perspective (graphical)|linear perspective]] technique and the use of optical aids in [[Renaissance]] art (see [[Hockney-Falco thesis]]).<ref>{{citation|first=Charles M.|last=Falco|title=Ibn al-Haytham and the Origins of Modern Image Analysis|date=12–15 February 2007|publisher=International Conference on Information Sciences, Signal Processing and its Applications}}</ref> The linear perspective technique was also employed in European [[Geography|geographical]] charts during the [[Age of Exploration]], such as [[Paolo Toscanelli]]'s chart which was used by [[Christopher Columbus]] when he went on a voyage to the [[New World]].<ref name=Powers/> |

|||

The theories of motion in [[Islamic physics]] developed by [[Avicenna]] and [[Ibn Bajjah|Avempace]] influenced [[Jean Buridan]]'s [[theory of impetus]], the ancestor of the [[inertia]] and [[momentum]] concepts, and the work of [[Galileo Galilei]] on [[classical mechanics]].<ref>Ernest A. Moody (1951), "Galileo and Avempace: The Dynamics of the Leaning Tower Experiment (I)", ''Journal of the History of Ideas'' '''12''' (2): 163-193</ref> The work of [[Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī]] and [[al-Khazini]] on [[mechanics]], particularly [[statics]] and [[dynamics]], were also adopted and further developed in medieval Europe.<ref name=Rozhanskaya-642>Mariam Rozhanskaya and I. S. Levinova (1996), "Statics", p. 642, in {{Harv|Morelon|Rashed|1996|pp=614-642}}</ref> |

|||

===Other works=== |

|||

Other Arabic works translated into Latin during the 12th century include the works of [[Rhazes|Razi]] and [[Avicenna]] (including ''[[The Book of Healing]]'' and ''[[The Canon of Medicine]]''),<ref>M.-T. d'Alverny, "Translations and Translators," pp. 444-6, 451</ref> |

|||

the works of [[Averroes]],<ref name=Campbell-3/> |

|||

the works of [[Thabit ibn Qurra]], [[al-Farabi]], [[Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Kathīr al-Farghānī]], [[Hunayn ibn Ishaq]], and his nephew Hubaysh ibn al-Hasan,<ref>D. Campbell, ''Arabian Medicine and Its Influence on the Middle Ages'', p. 4-5.</ref> |

|||

the works of [[al-Kindi]], [[Abraham bar Hiyya]]'s ''Liber embadorum'', Ibn Sarabi's ([[Serapion]] Junior) ''De Simplicibus'',<ref name=Campbell-3/> |

|||

the works of [[Qusta ibn Luqa]],<ref>D. Campbell, ''Arabian Medicine and Its Influence on the Middle Ages'', p. 5.</ref> |

|||

the works of [[Maslamah Ibn Ahmad al-Majriti]], [[Ja'far ibn Muhammad Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi]], and [[al-Ghazali]],<ref name=Zaimeche>Salah Zaimeche (2003). [http://www.muslimheritage.com/uploads/Main%20-%20Aspects%20of%20the%20Islamic%20Influence1.pdf Aspects of the Islamic Influence on Science and Learning in the Christian West], p. 10. Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation.</ref> |

|||

the works of [[Nur Ed-Din Al Betrugi]], including ''On the Motions of the Heavens'',<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bautz.de/bbkl/m/michael_sco.shtml|title=''Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexicon''}}</ref><ref name=Bieber/> |

|||

[[Ali ibn Abbas al-Majusi]]'s medical encyclopedia, ''The Complete Book of the Medical Art'',<ref name=Bieber>Jerome B. Bieber. [http://inst.santafe.cc.fl.us/~jbieber/HS/trans2.htm Medieval Translation Table 2: Arabic Sources], [[Santa Fe Community College (Florida)|Santa Fe Community College]].</ref> |

|||

[[Abu Mashar]]'s ''Introduction to Astrology'',<ref>Charles Burnett, ed. ''Adelard of Bath, Conversations with His Nephew,'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), p. xi.</ref> |

|||

the works of [[Maimonides]], Ibn Zezla (Byngezla), [[Masawaiyh]], [[Serapion]], al-Qifti, and Albe'thar.<ref>D. Campbell, ''Arabian Medicine and Its Influence on the Middle Ages'', p. 4.</ref> |

|||

[[Abū Kāmil Shujā ibn Aslam]]'s ''Algebra'',<ref name=Katz>V. J. Katz, ''A History of Mathematics: An Introduction'', p. 291.</ref> |

|||

and the ''De Proprietatibus Elementorum'', an [[Islamic geography|Arabic work on geology]] written by a [[pseudo-Aristotle]].<ref name=Bieber/> By the beginning of the 13th century, [[Mark of Toledo]] translated the [[Qur'an]] and various [[Islamic medicine|medical works]].<ref>M.-T. d'Alverny, "Translations and Translators," pp. 429, 455</ref> |

|||

[[Ibn Tufail]]'s ''[[Hayy ibn Yaqdhan]]'' was translated into Latin by [[Edward Pococke]] in 1671 and into English by [[Simon Ockley]] in 1708 and became "one of the most important books that heralded the [[Scientific Revolution]]."<ref>Samar Attar, ''The Vital Roots of European Enlightenment: Ibn Tufayl's Influence on Modern Western Thought'', Lexington Books, ISBN 0739119893.</ref> [[Ibn al-Baitar]]'s ''Kitab al-Jami fi al-Adwiya al-Mufrada'' also had an influence on European [[botany]] after it was translated into Latin in 1758.<ref>Russell McNeil, [http://www.mala.bc.ca/~mcneil/baitart.htm Ibn al-Baitar], [[Malaspina University-College]]</ref> |

|||

==Islamic techniques== |

|||

In the 12th century, Europe owed Islam an agricultural revolution (see [[Muslim Agricultural Revolution]]), due to the progressive introduction into Europe of various unknown fruits: the [[artichoke]], [[spinach]]s, [[aubergines]], [[peaches]], [[apricots]].<ref>Roux, p. 47</ref> Various mechanical and agricultural equipment was adopted from Islamic lands, such as the [[noria]] and the [[windmill]]. |

|||

Numerous new techniques in clothing, as well as new materials were also introduced: [[muslin]], [[taffeta]]s, [[satin]], [[skirts]]. Trade mechanisms were also transmitted: [[tarif]]s, [[customs]], [[bazar]]s, magazins. |

|||

[[Image:Arabo-NormanArchitecture.JPG|thumb|left|[[Arab-Norman culture|Arab-Norman]] art and architecture combined Occidental features (such as the Classical pillars and friezes) with typical [[Islamic art|Islamic decorations]] and [[Islamic calligraphy|calligraphy]].<ref>”Les Normans en Sicile”</ref>]] |

|||

===Arts=== |

|||

{{see also|Islamic art}} |

|||

Numerous techniques from [[Islamic art]] formed the basis of Arab-Norman art: inlays in [[mosaic]]s or [[metal]]s, sculpture of [[ivory]] or [[porphyry]], sculpture of hard stones, bronze [[Foundry|foundries]], manufacture of [[silk]] (for which [[Roger II of Sicily]] established a ''regium ergasterium'', a state enterprise which would give [[Sicily]] the monopoly of silk manufacture for all Europe).<ref>Pierre Aubé (2006), ''Les empires normands d’Orient'', p. 164-5, Editions Perrin, ISBN 2262022976</ref> |

|||

===Architecture=== |

|||

{{see also|Islamic architecture}} |

|||

[[Gothic architecture]] was influenced by [[Islamic architecture]]. In particular, the pointed [[arch]] was introduced to Europe after the [[Norman conquest of southern Italy|Norman conquest]] of [[History of Islam in southern Italy|Islamic Sicily]] in 1090, the [[Crusades]] which began in 1096, and the [[Al-Andalus|Islamic presence in Spain]], which all brought about a knowledge of this significant structural device. It is probable also that decorative carved stone screens and window openings filled with pierced stone also influenced Gothic tracery. In Spain, in particular, individual decorative motifs occur which are common to both Islamic and Christian architectural mouldings and sculpture.<ref>[[Christopher Wren]] (1750). ''Parentalia: or, Memoirs of the family of the Wrens'', viz. of Mathew Bishop, printed for T. Osborn; and R. Dodsley, London.</ref><ref>[http://muslimheritage.com/topics/default.cfm?ArticleID=385 Christopher Wren and the Muslim Origin of Gothic Architecture] (2003), Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation.</ref> |

|||

===Institutions=== |

|||

Europe adopted a number of educational, legal and scientific [[institution]]s from the Islamic world, including the [[public hospital]] (which replaced [[healing temple]]s and [[sleep temple]]s)<ref name=Barrett/> and [[psychiatric hospital]],<ref name=Syed>Ibrahim B. Syed PhD, "Islamic Medicine: 1000 years ahead of its times", ''[[The Islamic Medical Association of North America|Journal of the Islamic Medical Association]]'', 2002 (2), p. 2-9 [7-8].</ref> the [[public library]] and [[lending library]], the [[academic degree]]-granting [[university]] (see [[Madrasah]]), the astronomical [[observatory]] as a [[research institute]]<ref name=Barrett>[[Peter Barrett]] (2004), ''Science and Theology Since Copernicus: The Search for Understanding'', p. 18, [[Continuum International Publishing Group]], ISBN 056708969X.</ref> (as opposed to a private [[observation post]] as was the case in ancient times)<ref>{{citation|last=Micheau|first=Francoise|contribution=The Scientific Institutions in the Medieval Near East|pages=992-3}}, in {{Harv|Rashed|Morelon|1996|pp=985-1007}}</ref> (see [[Islamic astronomy]]), the [[trust law|trust]] institution and [[charitable trust]] (see [[Waqf]]),<ref>{{Harv|Gaudiosi|1988}}</ref><ref>{{Harv|Hudson|2003|p=32}}</ref> the [[Agency (law)|agency]] and [[aval]] ([[Hawala]]),<ref name="citationIslamic1">{{citation|title=Islamic Law: Its Relation to Other Legal Systems|first=Gamal Moursi|last=Badr|journal=The American Journal of Comparative Law|volume=26|issue=2 - Proceedings of an International Conference on Comparative Law, Salt Lake City, Utah, February 24-25, 1977|date=Spring, 1978|pages=187-198 [196-8]}}</ref> and a variety of other such institutions. |

|||

===Music=== |

|||

{{main|Arabic music|Andalusian classical music}} |

|||

{{see also|Inventions in the Islamic world}} |

|||

[[Image:Lautenmacher-1568.png|thumb|The [[lute]] was adopted from the Arab world. 1568 print.]] |

|||

A number of [[musical instrument]]s used in [[Western music]] are believed to have been derived from [[Arabic music]]al instruments: the [[lute]] was derived from the ''[[Oud|al'ud]]'', the [[rebec]] (ancestor of [[violin]]) from the ''[[rebab]]'', the [[guitar]] from ''qitara'', [[naker]] from ''[[naqareh]]'', [[adufe]] from ''[[Daf|al-duff]]'', [[alboka]] from ''al-buq'', [[Naffir|anafil]] from ''al-nafir'', exabeba from ''al-shabbaba'' ([[flute]]), atabal ([[bass drum]]) from ''al-tabl'', atambal from ''al-tinbal'',<ref>{{Harv|Farmer|1988|p=137}}</ref> |

|||

the [[Balaban (instrument)|balaban]], the [[castanet]] from ''kasatan'', [[Tuna (music)|sonajas de azófar]] from ''sunuj al-sufr'', the [[Bore (wind instruments)|conical bore]] [[wind instrument]]s,<ref>{{Harv|Farmer|1988|p=140}}</ref> the xelami from the ''sulami'' or ''[[fistula]]'' (flute or [[Organ pipe|musical pipe]]),<ref>{{Harv|Farmer|1988|pp=140-1}}</ref> |

|||

the [[shawm]] and [[dulzaina]] from the [[Reed (instrument)|reed instruments]] ''zamr'' and ''[[Zurna|al-zurna]]'',<ref>{{Harv|Farmer|1988|p=141}}</ref> |

|||

the [[Galician gaita|gaita]] from the ''[[Rhaita|ghaita]]'', [[rackett]] from ''iraqya'' or ''iraqiyya'',<ref>{{Harv|Farmer|1988|p=142}}</ref> |

|||

the [[harp]] and [[zither]] from the ''[[Kanun (instrument)|qanun]]'',<ref>{{cite web|author=Rabab Saoud|title=The Arab Contribution to the Music of the Western World|url=http://www.muslimheritage.com/uploads/Music2.pdf|publisher=FSTC Limited|date=March 2004|accessdate=2008-06-20}}</ref> |

|||

[[Canon (music)|canon]] from ''qanun'', [[Violin|geige]] (violin) from ''ghichak'',<ref>{{Harv|Farmer|1988|p=143}}</ref> |

|||

and the [[theorbo]] from the ''tarab''.<ref>{{Harv|Farmer|1988|p=144}}</ref> |

|||

According to a common theory on the origins of the [[troubadour]], a composer of medieval [[lyric poetry]], it may have had Arabic origins. [[Ezra Pound]], in his ''Canto VIII'', famously declared that William of Aquitaine "had brought the song up out of Spain / with the singers and veils..." referring to the troubadour song. In his study, Lévi-Provençal is said to have found four Arabo-Hispanic verses nearly or completely recopied in William's manuscript. According to historic sources, [[William VIII of Aquitaine|William VIII]], the father of William, brought to Poitiers hundreds of Muslim prisoners.<ref>M. Guettat (1980), ''La Musique classique du Maghreb'' (Paris: Sindbad).</ref> Trend admitted that the troubadours derived their sense of form and even the subject matter of their poetry from the Andalusian Muslims.<ref>J. B. Trend (1965), ''Music of Spanish History to 1600'' (New York: Krause Reprint Corp.)</ref> The hypothesis that the troubadour tradition was created, more or less, by William after his experience of [[Moorish]] arts while fighting with the [[Reconquista]] in Spain was also championed by [[Ramón Menéndez Pidal]] in the early twentieth-century, but its origins go back to the ''[[Cinquecento]]'' and Giammaria Barbieri (died 1575) and [[Juan Andrés]] (died 1822). Meg Bogin, English translator of the trobairitz, held this hypothesis. Certainly "a body of song of comparable intensity, profanity and eroticism [existed] in Arabic from the second half of the 9th century onwards."<ref>"Troubadour", ''[[Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians]]'', edited by Stanley Sadie, Macmillan Press Ltd., London</ref> |

|||

Another theory on the origins of the Western [[solfège]] musical notation suggests that it may have also had Arabic origins. It has been argued that the solfège syllables (''do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti'') may have been derived from the syllables of the Arabic [[solmization]] system ''Durr-i-Mufassal'' ("Separated Pearls") (''dal, ra, mim, fa, sad, lam''). This origin theory was first proposed by Meninski in his ''Thesaurus Linguarum Orientalum'' (1680) and then by Laborde in his ''Essai sur la Musique Ancienne et Moderne'' (1780).<ref>{{Harv|Farmer|1988|pp=72-82}}</ref><ref>{{citation|title=Guido d'Arezzo: Medieval Musician and Educator|first=Samuel D.|last=Miller|journal=Journal of Research in Music Education|volume=21|issue=3|date=Autumn 1973|pages=239-45}}</ref> |

|||

===Technology=== |

|||

{{see also|Inventions in the Islamic world|Muslim Agricultural Revolution|Timeline of Muslim scientists and engineers}} |

|||

A number of [[Timeline of Muslim scientists and engineers|technologies in the Islamic world]] were adopted in European [[medieval technology]]. These included Indian inventions such as [[chess]] and various [[crops]];<ref name=Watson/> Chinese inventions such as [[gunpowder]], [[paper]] and [[woodblock printing]];<ref>Richard W. Bulliet (1987), "Medieval Arabic Tarsh: A Forgotten Chapter in the History of Printing", ''Journal of the American Oriental Society'' '''107''' (3), p. 427-438.</ref> Greek inventions such as the [[astrolabe]]; and a variety of original [[Inventions in the Islamic world|Muslim inventions]], including [[Islamic astronomy|astronomical instruments]] such as the [[Quadrant (instrument)|quadrant]] (including the ''Quadrans Vetus'', a universal horary quadrant which could be used for any [[latitude]],<ref name=King-2002>David A. King (2002). "A Vetustissimus Arabic Text on the Quadrans Vetus", ''Journal for the History of Astronomy'' '''33''', p. 237-255 [237-238].</ref> and the ''Quadrans Novus'', an astrolabic quadrant)<ref>Roberto Moreno, Koenraad Van Cleempoel, David King (2002). "A Recently Discovered Sixteenth-Century Spanish Astrolabe", ''Annals of Science'' '''59''' (4), p. 331-362 [333].</ref> and [[Sextant (astronomical)|sextant]], a universal astrolabe invented by [[Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm al-Zarqālī]] known as the ''Saphaea'' in Europe, the "observation tube" (without [[Lens (optics)|lens]]) which influenced the development of the [[telescope]],<ref>Regis Morelon, "General Survey of Arabic Astronomy", pp. 9-10, in {{Harv|Rashed|Morelon|1996|pp=1-19}}</ref> [[Abbas Ibn Firnas]]' [[hang glider]] flight which influenced [[Eilmer of Malmesbury]]'s [[glider]] flight,<ref name=White>[[Lynn Townsend White, Jr.]] (Spring, 1961). "Eilmer of Malmesbury, an Eleventh Century Aviator: A Case Study of Technological Innovation, Its Context and Tradition", ''Technology and Culture'' '''2''' (2), p. 97-111 [100-101].</ref> [[Cob (material)|cobwork]] (''tabya''),<ref>[[Donald Routledge Hill]] (1996), "Engineering", p. 766, in {{Harv|Rashed|Morelon|1996|pp=751-95}}</ref> [[street lamp]]s,<ref>[[Fielding H. Garrison]], ''History of Medicine''</ref> [[waste container]]s and [[waste disposal]] facilities for [[litter]] collection,<ref>S. P. Scott (1904), ''History of the Moorish Empire in Europe'', 3 vols, J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia and London. <br> F. B. Artz (1980), ''The Mind of the Middle Ages'', Third edition revised, [[University of Chicago Press]], pp 148-50. <br> ([[cf.]] [http://www.1001inventions.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=main.viewSection&intSectionID=441 References], 1001 Inventions)</ref> [[Maintaining power|weight-driven]] mechanical [[clock]]s with [[escapement]] mechanisms,<ref name=Hassan>[[Ahmad Y Hassan]], [http://www.history-science-technology.com/Articles/articles%2071.htm Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part II: Transmission Of Islamic Engineering], ''History of Science and Technology in Islam''</ref> segmental [[gear]]s<ref>[[Lynn Townsend White, Jr.]], quoted in [http://www.finns-books.com/auto.htm The Automata of Al-Jazari], The [[Topkapi Palace]] Museum, [[Istanbul]]</ref> ("a piece for receiving or communicating [[reciprocating motion]] from or to a [[cogwheel]], consisting of a sector of a circular gear, or ring, having [[Gear|cog]]s on the periphery, or face"),<ref>[http://www.thefreedictionary.com/Segment+gear Segment gear], [[TheFreeDictionary.com]]</ref> [[Distilled beverage|distilled]] [[alcohol]] ([[ethanol]]) described by [[Alchemy (Islam)|Muslim chemists]],<ref name=Hassan-Chemical>[[Ahmad Y Hassan]], [http://www.history-science-technology.com/Articles/articles%2072.htm Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part III: Technology Transfer in the Chemical Industries], ''History of Science and Technology in Islam''.</ref> over 200 surgical instruments described in [[Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi]]'s ''[[Al-Tasrif]]'', [[explosive]] compositions of [[gunpowder]],<ref name=Terzioglu>[[Tosun Terzioğlu|Arslan Terzioglu]] (2007), "The First Attempts of Flight, Automatic Machines, Submarines and Rocket Technology in Turkish History", in ''The Turks'' (ed. H. C. Guzel), pp. 804-810.</ref> the baculus used for nautical astronomy, the [[lateen]] [[sail]], the [[caravel]] ship and three-[[Mast (sailing)|masted]] [[merchant vessel]],<ref>John M. Hobson (2004), ''The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation'', p. 141, [[Cambridge University Press]], ISBN 0521547245.</ref> and a variety of other technologies. |

|||

The [[Muslim Agricultural Revolution]] in particular diffused a large number of [[crops]] and technologies into medieval Europe, where farming was mostly restricted to wheat strains obtained much earlier via central Asia. Spain received what she in turn transmitted to the rest of Europe; many agricultural and fruit-growing processes, together with many new plants, fruit and vegetables. These new crops included sugar cane, rice, citrus fruit, apricots, cotton, artichokes, aubergines, and saffron. Others, previously known, were further developed. Muslims also brought to that country lemons, oranges, cotton, almonds, figs and sub-tropical crops such as bananas and sugar cane. Several were later exported from Spanish coastal areas to the Spanish colonies in the New World. Also transmitted via Muslim influence, a silk industry flourished, flax was cultivated and linen exported, and [[esparto]] grass, which grew wild in the more arid parts, was collected and turned into various articles.<ref name=Watson>Andrew M. Watson (1974), "The Arab Agricultural Revolution and Its Diffusion, 700–1100", ''The Journal of Economic History'' '''34''' (1), pp. 8–35.</ref> Industries established for [[sugar plantation]]s,<ref>J. H. Galloway (1977), "The Mediterranean Sugar Industry", ''Geographical Review'' '''67''' (2), pp. 177–94.</ref> [[ceramic]]s, [[Chemical industry|chemicals]], [[distillation]] technologies, [[clock]]s, [[glass]], mechanical [[hydropower]]ed and [[wind power]]ed [[machine]]ry, [[mat]]ting, [[mosaic]]s, [[Pulp and paper industry|pulp and paper]], [[perfume]]ry, [[Petroleum industry|petroleum]], [[Pharmaceutical company|pharmaceuticals]], [[rope]]-making, [[shipping]], [[shipbuilding]], [[silk]], [[sugar]], [[Textile industry|textiles]], [[Water industry|water]], [[weapon]]s, and the [[mining]] of [[mineral]]s such as [[sulfur]], [[ammonia]], [[lead]] and [[iron]], were transferred from the Islamic world to medieval Europe.<ref>[[Ahmad Y Hassan]], [http://www.history-science-technology.com/Articles/articles%207.htm Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part 1: Avenues Of Technology Transfer]</ref> [[Factory]] installations and a variety of industrial [[Mill (grinding)|mills]] (including [[fulling]] mills, [[gristmill]]s, [[huller]]s, [[paper mill]]s, [[sawmill]]s, shipmills, [[stamp mill]]s, [[steel mill]]s, [[Sugar refinery|sugar mills]], [[tide mill]]s and [[windmill]]s) were also transmitted to medieval Europe,<ref>Adam Lucas (2006), ''Wind, Water, Work: Ancient and Medieval Milling Technology'', p. 10 & 65, BRILL, ISBN 9004146490.</ref> along with the [[crankshaft]]-[[connecting rod]] mechanism (invented by [[al-Jazari]]),<ref>[[Ahmad Y Hassan]]. [http://www.history-science-technology.com/Notes/Notes%203.htm The Crank-Connecting Rod System in a Continuously Rotating Machine].</ref> [[noria]] and [[chain pump]]s for irrigation purposes.<ref name=Idrisi>Zohor Idrisi (2005), [http://www.muslimheritage.com/uploads/AgricultureRevolution2.pdf The Muslim Agricultural Revolution and its influence on Europe], FSTC.</ref> These innovations made it possible for many industrial operations that were previously driven by [[manual labour]] to be driven by [[machine]]ry in medieval Europe, where the foundations for the [[Industrial Revolution]] were laid.<ref>Adam Robert Lucas (2005), "Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds: A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe", ''Technology and Culture'' '''46''' (1), p. 1-30.</ref> |

|||

==Economics== |

|||

{{main|Islamic economics in the world}} |

|||

Some writers trace back the earliest stages of merchant [[capitalism]] to the [[Caliphate]] during the 9th-12th centuries, where a vigorous [[monetary economy|monetary]] [[market economy]] was created on the basis of the expanding levels of circulation of a stable high-value [[currency]] (the [[dinar]]) and the integration of [[monetary]] areas that were previously independent. Innovative new [[business]] techniques and forms of [[business organization]] were introduced by [[economist]]s, [[merchant]]s and [[trader]]s during this time. Such innovations included [[trading company|trading companies]], [[bills of exchange]], [[contract]]s, long-distance [[trade]], [[big business]]es, the first forms of [[partnership]] (''mufawada'' in [[Arabic language|Arabic]]) such as [[limited partnership]]s (''mudaraba'') (''mufawada'' partnership possessed features similar to those of the medieval family ''compagnia'' in [[Europe]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0007-6805%28197223%2946%3A3%3C397%3APAPIMI%3E2.0.CO%3B2-R&size=LARGE&origin=JSTOR-enlargePage|title=Partnership and Profit in Medieval Islam by Abraham L. Udovitch}}</ref>), and the concepts of [[Credit (finance)|credit]], [[profit]], [[Capital (economics)|capital]] (''al-mal'') and [[capital accumulation]] (''nama al-mal''). Many of these early capitalist ideas were further advanced in [[Middle Ages|medieval Europe]] from the 13th century onwards.<ref name=Banaji>{{cite journal|author=Banaji, Jairus|year=2007|title=Islam, the Mediterranean and the rise of capitalism|journal=Journal Historical Materialism|volume=15|pages=47–74|publisher=Brill Publishers|doi=10.1163/156920607X171591}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Shatzmiller, Maya|year=1994|title=Labour in the Medieval Islamic World|pages=402-403|publisher=Brill Publishers|isbn=9004098968}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|author=Labib, Subhi Y.|year=1969|title=Capitalism in Medieval Islam|journal=The Journal of Economic History|volume=29|pages=79–96}}</ref> |

|||

==Education== |

|||

{{main|Madrasah}} |

|||

The first [[University|universities]], namely institutions of [[higher education]] and [[research]] which issue [[academic degree]]s at all levels ([[Bachelor's degree|bachelor]], [[Master's degree|master]] and [[doctorate]]), were medieval [[Madrasah]]s known as ''Jami'ah'' founded in the 9th century.<ref name=G-Makdisi>{{citation|last=Makdisi|first=George|title=Scholasticism and Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West|journal=Journal of the American Oriental Society|volume=109|issue=2|date=April-June 1989|pages=175-182 [175-77]}}</ref><ref name=Alatas/> The [[University of Al Karaouine]] in [[Fez, Morocco]] is thus recognized by the [[Guinness World Records|Guinness Book of World Records]] as the oldest degree-granting university in the world with its founding in 859 by the princess Fatima al-Fihri.<ref>''The Guinness Book Of Records'', 1998, p. 242, ISBN 0-5535-7895-2</ref> The first universities in Europe were influenced in many ways by the Madrasahs in [[Al-Andalus|Islamic Spain]] and the [[Emirate of Sicily]] at the time, and in the Middle East during the Crusades.<ref name=G-Makdisi/> |

|||

Some of the terms and concepts now used in modern universities which have Islamic origins include "the fact that we still talk of [[professor]]s holding the '[[Chair (official)|Chair]]' of their subject" being based on the "traditional Islamic pattern of teaching where the professor sits on a chair and the students sit around him", the term '[[Study circle|academic circles]]' being derived from the way in which Islamic students "sat in a circle around their professor", and terms such as "having '[[fellow]]s', '[[Reading (for degree)|reading]]' a subject, and obtaining 'degrees', can all be traced back" to the Islamic concepts of ''Ashab'' ("[[Sahaba|companions]], as of the prophet [[Muhammad]]"), ''Qara'a'' ("reading aloud the [[Qur'an]]") and ''[[Ijazah]]'' ("license to teach") respectively. George Makdisi has listed eighteen such parallels in terminology which can be traced back to their roots in Islamic education. Some of the practices now common in modern universities which also have Islamic origins include "practices such as delivering [[Inauguration|inaugural]] [[lecture]]s, wearing [[Academic dress|academic robes]], obtaining doctorates by defending a [[Dissertation|thesis]], and even the idea of [[academic freedom]] are also modelled on Islamic custom." Islamic influence was also "certainly discernible in the foundation of the first delibrately-planned university" in Europe, the [[University of Naples Federico II]] founded by [[Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor]] in 1224.<ref name="RelationsHughGoddard1">{{citation|title=A History of Christian-Muslim Relations|first=Hugh|last=Goddard|year=2000|publisher=[[Edinburgh University Press]]|isbn=074861009X|page=100}}</ref> |

|||

Madrasahs were also the first [[law school]]s, and it is likely that the "law schools known as [[Inns of Court]] in England" may have been derived from the Madrasahs which taught [[Sharia|Islamic law]] and [[Fiqh|jurisprudence]].<ref name=J-Makdisi/> |

|||

The origins of the doctorate dates back to the ''[[Ijazah|ijazat attadris wa 'l-ifttd]]'' ("license to teach and issue legal opinions") in the medieval Islamic [[legal education]] system, which was equivalent to the [[Doctor of Laws]] qualification and was developed during the 9th century after the formation of the ''[[Madh'hab]]'' legal schools. To obtain a doctorate, a student "had to study in a [[guild]] [[Law school|school of law]], usually four years for the basic [[Undergraduate education|undergraduate]] course" and ten or more years for a [[Postgraduate education|post-graduate]] course. The "doctorate was obtained after an oral [[Test (student assessment)|examination]] to determine the originality of the candidate's [[Dissertation|theses]]," and to test the student's "ability to defend them against all objections, in [[disputation]]s set up for the purpose" which were scholarly exercises practiced throughout the student's "career as a [[Graduate school|graduate student]] of law." After students completed their post-graduate education, they were awarded doctorates giving them the status of ''[[faqih]]'' (meaning "[[master of law]]"), ''[[mufti]]'' (meaning "professor of [[Fatwā|legal opinions]]") and ''mudarris'' (meaning "teacher"), which were later translated into Latin as ''[[Magister (degree)|magister]]'', ''[[professor]]'' and ''doctor'' respectively.<ref name=G-Makdisi>{{citation|last=Makdisi|first=George|title=Scholasticism and Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West|journal=Journal of the American Oriental Society|volume=109|issue=2|date=April-June 1989|pages=175-182 [175-77]}}</ref> |

|||

The term ''doctorate'' comes from the Latin ''docere'', meaning "to teach", shortened from the full Latin title ''licentia docendi'' meaning "license to teach." This was translated from the [[Arabic language|Arabic]] term ''ijazat attadris'', which means the same thing and was awarded to [[Ulema|Islamic scholars]] who were qualified to teach. Similarly, the Latin term ''doctor'', meaning "teacher", was translated from the Arabic term ''mudarris'', which also means the same thing and was awarded to qualified Islamic teachers.<ref name=G-Makdisi/> The Latin term ''[[baccalaureus]]'' may have also been transliterated from the equivalent Arabic qualification ''bi haqq al-riwaya'' ("the right to teach on the authority of another").<ref name=Alatas>{{citation|title=From Jami`ah to University: Multiculturalism and Christian–Muslim Dialogue|first=Syed Farid|last=Alatas|journal=Current Sociology|volume=54|issue=1|pages=112-32}}</ref> |

|||

The Islamic scholarly system of ''[[fatwa]]'' and ''[[ijma]]'', meaning [[opinion]] and [[consensus]] respectively, formed the basis of the "scholarly system the [[Western world|West]] has practised in university [[scholarship]] from the Middle Ages down to the present day."<ref name=G-Makdisi/> According to George Makdisi and Hugh Goddard, "the idea of [[academic freedom]]" in [[University|universities]] was "modelled on Islamic custom" as practiced in the medieval Madrasah system from the 9th century. Islamic influence was "certainly discernible in the foundation of the first delibrately-planned university" in Europe, the [[University of Naples Federico II]] founded by [[Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor]] in 1224.<ref name="RelationsHughGoddard1"/> |

|||

==Law== |

|||

{{main|Sharia|Fiqh}} |

|||

Several fundamental [[common law]] instutitions may have been adapted from similar legal instututions in [[Sharia|Islamic law]] and [[Fiqh|jurisprudence]], and introduced to England after the [[Norman conquest of England]] by the [[Normans]], who conquered and inherited the Islamic legal administration of the [[Emirate of Sicily]] (see [[Arab-Norman culture]]),<ref name=J-Makdisi/> "through the close connection between the Norman kingdoms of Roger II in Sicily — ruling over a conquered Islamic administration — and [[Henry II of England|Henry II in England]]."<ref>{{citation|first=Jamila|last=Hussain|title=Book Review: ''The Justice of Islam'' by Lawrence Rosen|journal=[[Melbourne University Law Review]]|volume=30|year=2001}}</ref> and also by Crusaders during the Crusades. In particular, the "royal English [[contract]] protected by the action of [[debt]] is identified with the Islamic ''Aqd'', the English [[assize of novel disseisin]] is identified with the Islamic ''Istihqaq'', and the English [[jury]] is identified with the Islamic ''Lafif''."<ref name=J-Makdisi>{{citation|last=Makdisi|first=John A.|title=The Islamic Origins of the Common Law|journal=[[North Carolina Law Review]]|year=1999|date=June 1999|volume=77|issue=5|pages=1635-1739}}</ref> The English [[Trust law|trust]] and [[Agency (law)|agency]] institutions in common law were possibly adapted from the Islamic ''[[Waqf]]'' and ''[[Hawala]]'' institutions respectively during the Crusades.<ref>{{Harvard reference |last=Gaudiosi |first=Monica M. |title=The Influence of the Islamic Law of Waqf on the Development of the Trust in England: The Case of Merton College |year=1988 |journal=[[University of Pennsylvania Law Review]] |volume=136 |issue=4 |date=April 1988 |pages=1231-1261}}</ref><ref name="citationIslamic1"/> |

|||

Other English legal institutions such as "the [[scholastic method]], the [[license]] to [[Education|teach]]," the "[[law school]]s known as [[Inns of Court]] in England and ''[[Madrasah|Madrasas]]'' in Islam" and the "European [[Limited partnership|commenda]]" (Islamic ''[[Qirad]]'') may have also originated from Islamic law.<ref name=J-Makdisi/> The methodology of legal [[precedent]] and reasoning by [[analogy]] (''[[Qiyas]]'') are also similar in both the Islamic and common law systems.<ref>{{citation|title=Islamic Finance: Law, Economics, and Practice|first=Mahmoud A.|last=El-Gamal|year=2006|publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]]|isbn=0521864143|page=16}}</ref> These similarities and influences have led some scholars to suggest that Islamic law may have laid the foundations for "the common law as an integrated whole".<ref name=J-Makdisi/> |

|||

Several legal [[institution]]s in [[Civil law (legal system)|civil law]] were also adapted from similar institutions in [[Sharia|Islamic law]] and [[Fiqh|jurisprudence]] during the [[Middle Ages]]. For example, the Islamic ''[[Hawala]]'' institution influenced the development of the ''Avallo'' in [[Italy|Italian]] civil law and the ''[[Aval]]'' in [[French civil law]].<ref name=Badr>{{citation|title=Islamic Law: Its Relation to Other Legal Systems|first=Gamal Moursi|last=Badr|journal=The American Journal of Comparative Law|volume=26|issue=2 [Proceedings of an International Conference on Comparative Law, Salt Lake City, Utah, February 24-25, 1977]|date=Spring, 1978|pages=187-198 [196-8]}}</ref> The ''commenda'' [[limited partnership]] used in European civil law was also adapted from the ''[[Qirad]]'' and ''Mudaraba'' in Islamic law. The civil law conception of ''[[res judicata]]''<ref name=J-Makdisi/> and the [[Balance transfer|transfer of debt]], which was not permissible under [[Roman law]] but is practiced in modern civil law, may also have origins in Islamic law. The concept of an [[Agency (law)|agency]] was also an "institution unknown to Roman law", where it was not possible for an individual to "conclude a binding [[contract]] on behalf of another as his [[Agent (law)|agent]]." The concept of an agency was introduced by [[Ulema|Islamic jurists]], and thus the civil law conception of agency may also have origins in Islamic law.<ref name=Badr/> |

|||

Islamic law also introduced "two fundamental principles to the West, on which were to later stand the future structure of law: [[Equity (law)|equity]] and [[good faith]]", which was a precursor to the concept of ''[[pacta sunt servanda]]'' in civil law and [[international law]]. Another influence of Islamic law on the civil law tradition was the [[presumption of innocence]], which was introduced to Europe by [[Louis IX of France]] soon after he returned from [[Palestine]] during the [[Crusades]]. Prior to this, European legal procedure consisted of either [[trial by combat]] or [[trial by ordeal]]. In contrast, Islamic law was based on the presumption of innocence from its beginning, as declared by the [[caliph]] [[Umar]] in the 7th century.<ref name=Boisard/> |

|||

There is evidence that early Islamic [[international law]] influenced the development of European international law, through various routes such as the Crusades, Norman conquest of the [[Emirate of Sicily]], and [[Reconquista]] of [[al-Andalus]].<ref name=Boisard>{{citation|title=On the Probable Influence of Islam on Western Public and International Law|first=Marcel A.|last=Boisard|journal=International Journal of Middle East Studies|volume=11|issue=4|date=July 1980|pages=429-50}}</ref> In particular, the Spanish jurist [[Francisco de Vitoria]], and his successor [[Grotius]], may have been influenced by Islamic international law through earlier Islamic-influenced writings such as the 1263 work ''[[Siete Partidas]]'' of [[Alfonso X]], which was regarded as a "monument of [[legal science]]" in Europe at the time and was influenced by the Islamic legal treatise ''Villiyet'' written in [[Al-Andalus|Islamic Spain]].<ref name=Boisard/><ref>{{citation|last=Weeramantry|first=Judge Christopher G.|title=Justice Without Frontiers: Furthering Human Rights|year=1997|publisher=[[Brill Publishers]]|isbn=9041102418}}</ref> |

|||

A number of Islamic legal concepts on [[human rights]] were also adopted in European legal systems, including concepts such as the [[charitable trust]], [[Trust law|trusteeship]] of property, [[social solidarity]], human [[dignity]], dignity of [[Labour (economics)|labour]], condemnation of [[antisocial behavior]], [[presumption of innocence]], notions of [[sharing]] and [[Duty of care|caring]], [[universalism]], fair [[industrial relations]], fair [[contract]], commercial [[integrity]], freedom from [[usury]], [[women's rights]], [[privacy]], [[abuse]] of rights, [[juristic person]]ality, [[individual freedom]], [[equality before the law]], [[Legal aid|legal representation]], non-[[retroactivity]], supremacy of the law, [[judicial independence]], judicial [[impartiality]], limited [[sovereignity]], [[tolerance]], and [[Islamic democracy|democratic participation]]. Many of these concepts were adopted in [[Middle Ages|medieval Europe]] through contacts with [[Islamic Spain]] and the [[Emirate of Sicily]], and through the Crusades and the [[Latin translations of the 12th century]].<ref>{{citation|title=Justice Without Frontiers|first=Christopher G.|last=Judge Weeramantry|year=1997|publisher=[[Brill Publishers]]|isbn=9041102418|pages=129-31}}</ref> After Sultan [[al-Kamil]] defeated the [[Franks]] during the [[Crusades]], Oliverus Scholasticus praised the Islamic [[laws of war]], commenting on how al-Kamil supplied the defeated Frankish army with food:<ref name=Weeramantry/> |

|||

{{quote|"Who could doubt that such goodness, friendship and charity come from God? Men whose parents, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, had died in agony at our hands, whose lands we took, whom we drove naked from their homes, revived us with their own food when we were dying of hunger and showered us with kindness even when we were in their power."<ref name=Weeramantry>{{citation|title=Justice Without Frontiers|first=Christopher G.|last=Judge Weeramantry|year=1997|publisher=[[Brill Publishers]]|isbn=9041102418|pages=136-7}}</ref>}} |

|||

==Literature== |

|||

{{see|Islamic literature|Arabic literature|Persian literature}} |

|||

The most well known [[fiction]] from the Islamic world was ''[[The Book of One Thousand and One Nights]]'' (''Arabian Nights''), which was a compilation of many earlier folk tales. The epic took form in the 10th century and reached its final form by the 14th century; the number and type of tales have varied from one manuscript to another.<ref name="arabianNights">John Grant and John Clute, ''The Encyclopedia of Fantasy'', "Arabian fantasy", p 51 ISBN 0-312-19869-8</ref> All Arabian [[fantasy]] tales were often called "Arabian Nights" when translated into [[English language|English]], regardless of whether they appeared in ''The Book of One Thousand and One Nights'', in any version, and a number of tales are known in Europe as "Arabian Nights" despite existing in no Arabic manuscript.<ref name="arabianNights"/> |

|||

[[Image:Ali-Baba.jpg|right|thumb|"[[Ali Baba]]" by [[Maxfield Parrish]].]] |

|||

This epic has been influential in the West since it was translated in the 18th century, first by [[Antoine Galland]].<ref>[[L. Sprague de Camp]], ''[[Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers]]: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy'', p 10 ISBN 0-87054-076-9</ref> Many imitations were written, especially in France.<ref name="arabianNights2">John Grant and John Clute, ''The Encyclopedia of Fantasy'', "Arabian fantasy", p 52 ISBN 0-312-19869-8</ref> Various characters from this epic have themselves become cultural icons in Western culture, such as [[Aladdin]], [[Sinbad]] and [[Ali Baba]]. However, no [[medieval]] Arabic source has been traced for [[Aladdin]], which was incorporated into ''[[The Book of One Thousand and One Nights]]'' by its [[French language|French]] translator, [[Antoine Galland]], who heard it from an [[Arab]] [[Syria]]n [[Christianity|Christian]] storyteller from [[Aleppo]]. Part of its popularity may have sprung from the increasing historical and geographical knowledge, so that places of which little was known and so marvels were plausible had to be set further "long ago" or farther "far away"; this is a process that continues, and finally culminate in the [[fantasy world]] having little connection, if any, to actual times and places. A number of elements from [[Arabian mythology]] and [[Persian mythology]] are now common in modern [[fantasy]], such as [[genie]]s, [[bahamut]]s, [[magic carpet]]s, magic lamps, etc.<ref name="arabianNights2"/> When [[L. Frank Baum]] proposed writing a modern fairy tale that banished stereotypical elements, he included the genie as well as the dwarf and the fairy as stereotypes to go.<ref>James Thurber, "The Wizard of Chitenango", p 64 ''Fantasists on Fantasy'' edited by Robert H. Boyer and Kenneth J. Zahorski, ISBN 0-380-86553-X</ref> |

|||

A famous example of [[Arabic poetry]] and [[Persian poetry]] on [[romance (love)]] is ''[[Layla and Majnun]]'', dating back to the [[Umayyad]] era in the 7th century. It is a [[Tragedy|tragic]] story of undying [[love]] much like the later ''[[Romeo and Juliet]]'', which was itself said to have been inspired by a [[Latin]] version of ''Layli and Majnun'' to an extent.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.shirazbooks.com/ebook1.html|title=Nizami: Layla and Majnun - English Version by Paul Smith}}</ref> |

|||

[[Ibn Tufail]] (Abubacer) was a pioneer of the [[philosophical novel]]. He wrote the first Arabic [[novel]], ''[[Hayy ibn Yaqdhan]]'' (''Philosophus Autodidactus''), which told the story of Hayy, an [[Autodidacticism|autodidactic]] [[feral child]] living in seclusion on a [[desert island]], being the earliest example of a desert island story.<ref>Dr. Abu Shadi Al-Roubi (1982), "Ibn Al-Nafis as a philosopher", ''Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis'', Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait ([[cf.]] [http://www.islamset.com/isc/nafis/drroubi.html Ibn al-Nafis As a Philosopher], ''Encyclopedia of Islamic World'').</ref><ref>Nahyan A. G. Fancy (2006), "Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288)", p. 95-101, ''Electronic Theses and Dissertations'', [[University of Notre Dame]].[http://etd.nd.edu/ETD-db/theses/available/etd-11292006-152615]</ref> A [[Latin]] translation of Ibn Tufail's ''Hayy ibn Yaqdhan'' first appeared in 1671, prepared by [[Edward Pococke]] the Younger, followed by an English translation by [[Simon Ockley]] in 1708, as well as [[German language|German]] and [[Dutch language|Dutch]] translations. These translations later inspired [[Daniel Defoe]] to write ''[[Robinson Crusoe]]'', regarded as the [[first novel in English]].<ref>Nawal Muhammad Hassan (1980), ''Hayy bin Yaqzan and Robinson Crusoe: A study of an early Arabic impact on English literature'', Al-Rashid House for Publication.</ref><ref>Cyril Glasse (2001), ''New [[Encyclopedia of Islam]]'', p. 202, Rowman Altamira, ISBN 0759101906.</ref><ref name=Amber>Amber Haque (2004), "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists", ''Journal of Religion and Health'' '''43''' (4): 357-377 [369].</ref><ref name=Wainwright>Martin Wainwright, [http://books.guardian.co.uk/review/story/0,12084,918454,00.html Desert island scripts], ''[[The Guardian]]'', 22 March 2003.</ref> ''Philosophus Autodidactus'' also inspired [[Robert Boyle]] to write his own philosophical novel set on an island, ''The Aspiring Naturalist''.<ref name=Toomer-222/> The story also anticipated [[Rousseau]]'s ''[[Emile: or, On Education]]'' in some ways, and is also similar to [[Mowgli]]'s story in [[Rudyard Kipling]]'s ''[[The Jungle Book]]'' as well as [[Tarzan]]'s story, in that a baby is abandoned but taken care of and fed by a mother [[wolf]].<ref>[http://www.muslimheritage.com/topics/default.cfm?ArticleID=808 Latinized Names of Muslim Scholars], FSTC.</ref> |

|||

There were several elements of [[courtly love]] which developed in Arabic literature. The notions of "love for love's sake" and "exaltation of the beloved lady" have been traced back to [[Arabic literature]] of the 9th and 10th centuries. The notion of the "ennobling power" of love was developed in the early 11th century by the [[Muslim psychology|Persian psychologist]] and [[Early Islamic philosophy|philosopher]], [[Avicenna|Ibn Sina]] (known as "Avicenna" in Europe), in his treatise ''Risala fi'l-Ishq'' (''Treatise on Love''). The final element of courtly love, the concept of "love as desire never to be fulfilled", was at times implicit in [[Arabic poetry]]. These elements influenced the development of courtly love in [[European literature]], in which all four elements of courtly love were present.<ref>G. E. von Grunebaum (1952), "Avicenna's Risâla fî 'l-'išq and Courtly Love", ''Journal of Near Eastern Studies'' '''11''' (4): 233-8 [233-4].</ref> |

|||

[[Dante Alighieri]]'s ''[[Divine Comedy]]'', considered the greatest epic of [[Italian literature]], derived many features of and episodes about the hereafter directly or indirectly from Arabic works on [[Islamic eschatology]]: the ''[[Hadith]]'' and the ''[[Kitab al-Miraj]]'' (translated into Latin in 1264 or shortly before<ref name="Heullant">I. Heullant-Donat and M.-A. Polo de Beaulieu, "Histoire d'une traduction," in ''Le Livre de l'échelle de Mahomet'', Latin edition and French translation by Gisèle Besson and Michèle Brossard-Dandré, Collection ''Lettres Gothiques'', Le Livre de Poche, 1991, p. 22 with note 37.</ref> as ''Liber Scale Machometi'', "The Book of Muhammad's Ladder") concerning [[Muhammad]]'s ascension to Heaven, and the spiritual writings of [[Ibn Arabi]]. The [[Moors]] also had a noticeable influence on the works of [[George Peele]] and [[William Shakespeare]]. Some of their works featured Moorish characters, such as Peele's ''[[The Battle of Alcazar]]'' and Shakespeare's ''[[The Merchant of Venice]]'', ''[[Titus Andronicus]]'' and ''[[Othello]]'', which featured a Moorish [[Othello (character)|Othello]] as its title character. These works are said to have been inspired by several Moorish [[delegation]]s from [[Morocco]] to [[Elizabethan England]] at the beginning of the 17th century.<ref>Professor Nabil Matar (April 2004), ''Shakespeare and the Elizabethan Stage Moor'', [[Sam Wanamaker]] Fellowship Lecture, Shakespeare’s [[Globe Theatre]] ([[cf.]] [[Mayor of London]] (2006), [http://www.london.gov.uk/gla/publications/equalities/muslims-in-london.pdf Muslims in London], pp. 14-15, Greater London Authority)</ref> |

|||

==Philosophy== |

|||

{{see also|Early Islamic philosophy|Avicennism|Averroism|Hayy ibn Yaqdhan|Transmission of Greek philosophical ideas in the Middle Ages}} |

|||

From [[Al-Andalus|Islamic Spain]], the [[Early Islamic philosophy|Arabic philosophical literature]] was translated into [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]], [[Latin]], and [[Ladino language|Ladino]], contributing to the development of modern European philosophy. The Jewish philosopher [[Moses Maimonides]], Muslim sociologist-historian [[Ibn Khaldun]], [[Carthage]] citizen [[Constantine the African]] who translated [[Greek language|Greek]] medical texts, and the Muslim [[Al-Khwarzimi]]'s collation of mathematical techniques were important figures of the Golden Age. |

|||

[[Image:AverroesColor.jpg|thumb|[[Averroes]], founder of the [[Averroism]] school of philosophy, was influential in the rise of [[secularism|secular thought]] in [[Western Europe]].<ref name=Fakhry/>]] |

|||

[[Avicenna]] founded the [[Avicennism]] school of philosophy, which was influential in both Islamic and Christian lands. He was a critic of [[Aristotelian logic]] and the founder of [[Avicennism#Avicennian logic|Avicennian logic]], and he developed the concepts of [[empiricism]] and [[tabula rasa]]. The main significance of [[Latin]] Avicennism lies in the interpretation of Avicennian doctrines such as the nature of the [[soul]] and his [[existence]]-[[essence]] distinction, along with the debates and censure that they raised in [[Scholasticism|scholastic Europe]]. This was particularly the case in [[Paris]], where Avicennism was later [[proscribed]] in 1210, though the influence of his [[Islamic psychological thought|psychology]] and theory of knowledge upon [[William of Auvergne]] and [[Albertus Magnus]] have been noted. The effects of Avicennism in [[Christianity]], however, was later submerged by [[Averroism]], a school of philosophy founded by [[Averroes]], one of the most influential Muslim philosophers in the West.<ref>Corbin (1993), p.174</ref> His works and commentaries had an impact on the rise of [[secularism|secular thought]] in [[Western Europe]],<ref name=Fakhry>Majid Fakhry (2001). ''Averroes: His Life, Works and Influence''. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 1851682694.</ref> and he also developed the concept of "[[existence precedes essence]]".<ref>{{citation|first=Jones|last=Irwin|title=Averroes' Reason: A Medieval Tale of Christianity and Islam|date=Autumn 2002|journal=The Philosopher|volume=LXXXX|issue=2}}</ref> |

|||

[[Al-Ghazali]] also had an important influence on [[Christian]] [[Medieval philosophy|medieval philosophers]] along with [[Jewish]] thinkers like [[Maimonides]].<ref>{{cite journal|journal=H-Net Review|title=Averroes (Ibn Rushd): His Life, Works and Influence|last=Ormsby|first=Eric}} See also: {{cite web|url=http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/maimonides-islamic/|title=The Influence of Islamic Thought on Maimonides|publisher=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy|accessdate=2008-08-28}}</ref> According to [[Margaret Smith (author)|Margaret Smith]], "There can be no doubt that Ghazali’s works would be among the first to attract the attention of these European scholars" and "The greatest of these Christian writers who was influenced by Al-Ghazali was St. [[Thomas Aquinas]] (1225–1274), who made a study of the Islamic writers and admitted his indebtedness to them. He studied at the [[University of Naples]] where the influence of Islamic literature and culture was predominant at the time."<ref>[[Margaret Smith (author)|Margaret Smith]], ''Al-Ghazali: The Mystic'' (London 1944)</ref> [[René Descartes]]' ideas from his ''[[Discourse on the Method]]'' were also influenced by al-Ghazali, and Descartes' method of [[doubt]] was very much similar to al-Ghazali's work.<ref name=Najm>{{citation|title=The Place and Function of Doubt in the Philosophies of Descartes and Al-Ghazali|first=Sami M.|last=Najm|journal=Philosophy East and West|volume=16|issue=3-4|date=July-October 1966|pages=133-41}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:AverroesAndPorphyry.JPG|thumb|Imaginary debate between [[Averroes]] and [[Porphyry]]. Monfredo de Monte Imperiali ''Liber de herbis'', 14th century.<ref>"Inventions et decouvertes au Moyen-Age", Samuel Sadaune, p.112</ref>]] |

|||

Another infuential philosopher who had a significant influence on [[modern philosophy]] was [[Ibn Tufail]]. His [[philosophical novel]], ''[[Hayy ibn Yaqdhan]]'', translated into Latin as ''Philosophus Autodidactus'' in 1671, developed the themes of empiricism, tabula rasa, [[nature versus nurture]],<ref>G. A. Russell (1994), ''The 'Arabick' Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England'', pp. 224-262, [[Brill Publishers]], ISBN 9004094598.</ref> [[condition of possibility]], [[materialism]],<ref>Dominique Urvoy, "The Rationality of Everyday Life: The Andalusian Tradition? (Aropos of Hayy's First Experiences)", in Lawrence I. Conrad (1996), ''The World of Ibn Tufayl: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Ḥayy Ibn Yaqẓān'', pp. 38-46, [[Brill Publishers]], ISBN 9004093001.</ref> and [[Molyneux's Problem]].<ref>Muhammad ibn Abd al-Malik [[Ibn Tufayl]] and Léon Gauthier (1981), ''Risalat Hayy ibn Yaqzan'', p. 5, Editions de la Méditerranée.[http://limitedinc.blogspot.com/2007/04/things-about-arabick-influence-on-john.html]</ref> European scholars and writers influenced by this novel include [[John Locke]],<ref>G. A. Russell (1994), ''The 'Arabick' Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England'', pp. 224-239, [[Brill Publishers]], ISBN 9004094598.</ref> [[Gottfried Leibniz]],<ref name=Wainwright/> [[Melchisédech Thévenot]], [[John Wallis]], [[Christiaan Huygens]],<ref>G. A. Russell (1994), ''The 'Arabick' Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England'', p. 227, [[Brill Publishers]], ISBN 9004094598.</ref> [[George Keith]], [[Robert Barclay]], the [[Religious Society of Friends|Quakers]],<ref>G. A. Russell (1994), ''The 'Arabick' Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England'', p. 247, [[Brill Publishers]], ISBN 9004094598.</ref> and [[Samuel Hartlib]].<ref name=Toomer-222>G. J. Toomer (1996), ''Eastern Wisedome and Learning: The Study of Arabic in Seventeenth-Century England'', p. 222, [[Oxford University Press]], ISBN 0198202911.</ref> |

|||

Certain aspects of [[Renaissance humanism]] also has its roots in the [[Islamic Golden Age|medieval Islamic world]], including the "art of ''[[Dictation (exercise)|dictation]]'', called in [[Latin]], ''[[ars dictaminis]]''," |

|||

and "the humanist attitude toward [[classical language]]."<ref>{{citation|last=Makdisi|first=George|title=Scholasticism and Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West|journal=Journal of the American Oriental Society|volume=109|issue=2|date=April-June 1989|pages=175-182}}</ref> There is also evidence that [[John Locke]]'s formulation of [[inalienable rights]] and conditional rulership, which were present in [[Islamic law]] centuries earlier, may have also been influenced by Islamic law, through his attendance of lectures given by [[Edward Pococke]], a professor of [[Islamic studies]].<ref>{{citation|title=Justice Without Frontiers|first=Christopher G.|last=Judge Weeramantry|year=1997|publisher=[[Brill Publishers]]|isbn=9041102418|pages=8, 135, 139-40}}</ref> |

|||

==Vocabulary== |

|||

{{main|Influence of Arabic on other languages|List of Arabic loanwords in English}} |

|||

{{see|List of Arabic star names|List of Latinised names}} |

|||

The adoption of the techniques and materials from the Islamic world is reflected in the origin of many of the words now in use in the Western world.<ref>Lebedel, p.113</ref> |

|||

{{Colbegin}} |

|||

*[[Admiral]], from ''amir al-bahr'' امير البحر (“Prince of the sea”) |

|||

*[[Alchemy]]/ [[Chemistry]], from ''al kemiya''' (الخيمياء) |

|||

*[[Algebra]], which comes from ''al-djabr'' |

|||

*[[Algorithm]], from the name of the scientist [[al-Khwarizmi]] |

|||

*[[Almanac]], from ''al-manakh'' (timetables) |

|||

*[[Amber]], from ''al-anbar'' |

|||

*[[Artichoke]], from ''al-karchouf'' |

|||

*Avarie (French for "ship damage"), from ''awar'' ("damage") |

|||

*[[Baldaquin]], from a tissue material made in Baghdad |

|||

*[[Camphor]], from ''kafur'' |

|||

*[[Carat (mass)]], from qīrāṭ (قيراط) ("mass") |

|||

*[[Coffee]], from ''Kahwa'' |

|||

*[[Cotton]], from ''koton'' |

|||

*[[Gauze]], from ''qazz'' ("raw silk") |

|||

*[[Hazard]], from ''az-zahr'' (game of dice) |

|||

*[[Lacquer]], from ''lakk'' |

|||

*[[Lute]], from ''al-ud'' |

|||

*[[Magazine]], from ''makhâzin'' |

|||

*[[Checkmate|Mate]] (as in "Checkmate"), from ''mât'' ("Death") |

|||

*[[Orange (word)|Orange]], from ''nârandj'' |

|||

*[[Racket]], from ''râhat'' (palm of the hand) |

|||

*[[Sorbet]], from ''sharab'' |

|||

*[[Sugar]], from ''soukkar'' |

|||

*[[Zero]], from Greek ''zephyrus'' which comes from ''şifr'' ("zero") |

|||

{{Colend}} |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

{{reflist|2}} |

|||

==References== |

|||

*{{Harvard reference|last=Farmer|first=Henry George|authorlink=Henry George Farmer|year=1988|title=Historical facts for the Arabian Musical Influence|publisher=Ayer Publishing|isbn=040508496X}} |

|||

*{{Harvard reference|last=Lebedel|first=Claude|title=Les Croisades, origines et conséquences|year=2006|publisher=Editions Ouest-France|isbn=2737341361}} |

|||