Martin Guerre: Difference between revisions

m robot Adding: pl:Martin Guerre |

|||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

== Historical account == |

== Historical account == |

||

The information in this section is taken from ([[#References|Davis 1983]]). |

The information in this section is taken from ([[#References|Davis 1983]]). It was used to produce this article in its entirity. |

||

=== Life before leaving his wife === |

=== Life before leaving his wife === |

||

Revision as of 05:20, 14 October 2008

Martin Guerre, a French peasant of the 16th century, was at the center of a famous case of imposture. Several years after he had left his family, a man claiming to be Guerre took his name and lived with Guerre's wife and son for three years. After a trial, during which the real Martin Guerre returned, the impostor Arnaud du Tilh was discovered and executed. The case continues to be studied and dramatized to this day.

Historical account

The information in this section is taken from (Davis 1983). It was used to produce this article in its entirity.

Life before leaving his wife

He was born as Martin Daguerre around 1524 in the Basque town of Hendaye. In 1527, his family moved to the Pyrenean village Artigat in southwestern France, where they changed their name to Guerre. When he was about fourteen years old, Martin was married to Bertrande de Rols, daughter of a well-off family. The marriage was childless for eight years until a son was born. Accused of stealing grain from his father, Martin abruptly disappeared in 1548. Catholic law governing France did not allow his abandoned wife to remarry (unlike that of the Protestants, who were slowly gaining ground; see French Wars of Religion).

"New Martin" appears

In the summer of 1556, a man appeared in Artigat, claiming to be Martin Guerre. By his similar looks and detailed knowledge of Martin Guerre's life, he convinced most of the villagers. Martin Guerre's uncle and four sisters as well as Bertrande believed that he was indeed Martin Guerre, although doubts remained. The “new” Martin lived for three years with Bertrande and her son; they had two children together, with one daughter surviving. “Martin” claimed the inheritance of Guerre's father, who had since died, and even sued Guerre's uncle, Pierre Guerre, for part of the inheritance.

Pierre Guerre, who had earlier married Bertrande's widowed mother during Martin Guerre's absence, then became suspicious again. He and his wife tried to convince Bertrande that the new Martin was an impostor. A soldier who passed through Artigat claimed that the new Martin Guerre was a fraud: the real one had lost a leg in the war. Pierre and his sons-in-law beat the new Martin with a club, but Bertrande intervened.

In 1559, the new Martin was accused of arson and also of impersonating Martin Guerre; Bertrande remained on his side, and he was acquitted in 1560.

Trial in Rieux

In the meantime, Pierre Guerre had asked around and believed to have found the true identity of the impostor: Arnaud du Tilh, nicknamed "Pansette", a man with a poor reputation from the nearby village Sajas. Pierre then initiated a new case against the man by falsely claiming to act in Bertrande's name. He and his wife, Bertrande's mother, pressured Bertrande to support the charge, and eventually she obliged.

In 1560, the case was tried in Rieux. Bertrande testified that at first she had honestly believed the man to be her husband, but that she had since realized that he was a fraud. Both Bertrande and the accused independently related an identical story about their intimate life from before 1548. The new Martin then challenged her: if she would swear that he was not her husband, he would gladly agree to be executed – Bertrande remained silent. After hearing more than 150 witnesses, with many recognizing Martin Guerre (including his four sisters), many recognizing Arnaud du Tilh and many refusing to take a side, the accused impostor was sentenced to death.

Appeal in Toulouse, Martin reappears

He immediately appealed to the parliament in Toulouse. Bertrande and Pierre were arrested: for possible false accusation and, in the case of Pierre, soliciting perjury. The new Martin eloquently argued his case, and the judges in Toulouse tended to believe his version of the story: that Bertrande was pressured to perjury by the greedy Pierre Guerre. The accused had to undergo detailed questioning about his past; his statements were double checked and no contradictions were found. But then dramatically the true Martin Guerre appeared during the very trial, with a wooden leg. When asked about their past, the new Martin was able to answer some questions better than the "old" one, who had forgotten several details. But when the two were presented to the Guerre family, the case was closed: Pierre, Bertrande, and Martin's four sisters all agreed that the old one was the true one. The impostor, who maintained his innocence, was convicted and sentenced to death for adultery and fraud; the public sentencing on September 12, 1560 was attended by the young Montaigne. Afterwards, Arnaud du Tilh confessed: he had learned about Guerre's life after two men confused him with Guerre, and he had then decided to take Guerre's place, with two conspirators helping him with the details. He apologized to all involved, including Bertrande, for having deceived them, and was hanged in front of Martin Guerre's house in Artigat four days later.

Martin's story

During the absence from his family, the real Martin Guerre had moved to Spain, served for a cardinal, and then later in the army of Pedro de Mendoza. As part of the Spanish army, he was eventually sent to Flanders and participated in the Spanish attack on St. Quentin on August 10, 1557. There he was wounded and his leg had to be amputated. He then lived in a monastery before returning to his wife. The reason for his returning at the very time of the trial remains unknown. Initially, he rejected his wife's apologies, maintaining that she should have known better than to take another man.

Reactions and interpretations

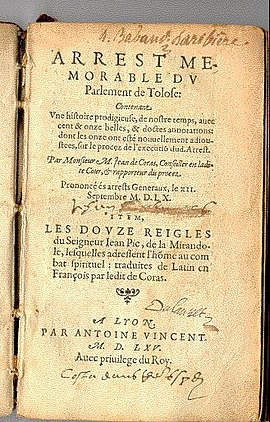

Two contemporary accounts of the case were written: Histoire Admirable by Guillaume Le Sueur and the better known Arrest Memorable by Jean de Coras, one of the trial judges in Toulouse. Throughout the ages, the bizarre story has fascinated many writers. Alexandre Dumas, père, included a fictionalized version of the story in his novel The Two Dianas as well as in his multi-volume Celebrated Crimes (1841).

A detailed account of the case was provided in 1983 by Princeton history professor Natalie Zemon Davis (Davis 1983). In her book, Davis argues that Bertrande silently or explicitly agreed to the fraud because she needed a husband and was treated well by Arnaud. The improbability of mistaking a stranger for her husband, her support for him until (and in a way even during) the very trial, and the shared intimate story which was likely prepared in advance are cited as evidence.

The historian Robert Finlay has criticized this conclusion (Finlay 1988), arguing that Bertrande was genuinely duped (as was widely believed by her contemporaries, including her trial judges) and that Davis tried to fit a modern societal model onto the historical account. He points to the improbability of Bertrande accusing her own accomplice, leading to a highly complicated situation where she runs the risk of having to defend herself against charges of adultery or false accusation. Davis attempted to rebut these arguments in the article "On the Lame" (Davis 1988).

The historical romance The Wife of Martin Guerre by Janet Lewis (first published 1941) is a speculation about Bertrande's true motives. It describes the physical appearance of Martin with rich detail:

Outwardly, Martin had the swarthy skin, the high forehead, the grey eyes, the flat, short nose, the lips, the high cleft chin of his father, and something of his father's build. Too early labour at the plough had rounded his shoulders. Nevertheless he was a skilful swordsman and boxer, agile, tall, and well-developed for his years. 'Not a pretty man,' as the servant had said, 'but a very distinguished man.' His ugliness was ancestral, and that in itself was good.

— The Wife of Martin Guerre, Janet Lewis[1]

The 1982 film Le Retour de Martin Guerre (directed by Daniel Vigne and starring Gérard Depardieu and Nathalie Baye) remains mostly true to the historic account, except for the fictional explanation of Bertrande's motives at the film's end. Natalie Davis served as a consultant for that film. Sommersby, a 1993 Hollywood film starring Jodie Foster and Richard Gere, retells the story placed in the United States after the American Civil War.

A musical named Martin Guerre by Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil, of Les Misérables fame, was premiered in London at the Prince Edward Theatre in 1996. The end of this musical is also not true to the historical account.

References

- Natalie Zemon Davis, The Return of Martin Guerre, Harvard University Press, 1983, ISBN 0-674-76691-1

- Robert Finlay, "The Refashioning of Martin Guerre", The American Historical Review, Vol. 93, No. 3. (June 1988), pp. 553-571. A criticism of the book's conclusions.

- Natalie Zemon Davis, "On The Lame", The American Historical Review, Vol. 93, No. 3. (June 1988), pp. 572-603. Defense of her conclusions.

- Richard Burt, Medieval and Early Modern Film and Media (Palgrave MacMillan, 2008) ISBN-10: 0230601251

External links

- Arrest Memorable by Jean de Coras, translation of the main text by Jeannette K Ringold.

- Martin Guerre, fictionalized account by Alexandre Dumas, père, part of the Celebrated Crimes series.

- ^ Lewis, J. (1977), The Wife of Martin Guerre, Penguin, London.