Miranda v. Arizona: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 64.8.149.146 to last revision by Versus22 (HG) |

|||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

During the 1960s, a movement which provided [[defendant]]s with [[legal aid]] emerged from the collective efforts of various [[bar association]]s. |

During the 1960s, a movement which provided [[defendant]]s with [[legal aid]] emerged from the collective efforts of various [[bar association]]s. |

||

In the [[Civil law (common law)|civil]] realm, it led to the creation of the [[Legal Services Corporation]] under the [[Great Society]] program of [[Lyndon Baines Johnson]]. ''[[Escobedo v. Illinois]],'' {{ussc|378|478|1964}}, a case which closely foreshadowed ''Miranda,'' provided for the presence of counsel during police interrogation. This concept extended to a concern over police [[interrogation]] practices, which were considered by many to be barbaric and unjust. Coercive interrogation tactics were known in period [[slang]] as the "[[third degree]]." |

In the [[Civil law (common law)|civil]] realm, it led to the creation of the [[Legal Services Corporation]] under the [[Great Society]] program of [[Lyndon Baines Johnson]]. ''[[Escobedo v. Illinois]],'' {{ussc|378|478|1964}}, a case which closely foreshadowed ''Miranda,'' provided for the presence of counsel during police interrogation. This concept extended to a concern over police [[interrogation]] practices, which were considered by many to be barbaric and unjust. Coercive interrogation tactics were known in period [[slang]] as the "[[third degree]]."CHUPAS!!!! |

||

===Arrest and conviction=== |

===Arrest and conviction=== |

||

Revision as of 17:45, 5 March 2009

| Miranda v. Arizona | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued February 28 – March 1, 1966 Decided June 13, 1966 | |

| Full case name | Miranda v. State of Arizona; Westover v. United States; Vignera v. State of New York; State of California v. Stewart |

| Citations | 384 U.S. 436 (more) 86 S. Ct. 1602; 16 L. Ed. 2d 694; 1966 U.S. LEXIS 2817; 10 A.L.R.3d 974 |

| Argument | Oral argument |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Defendant convicted, Ariz. Superior Ct.; affirmed, 401 P.2d 721 (Ariz. 1965); cert. granted, 382 U.S. 925 (1965) |

| Subsequent | Retrial on remand, defendant convicted, Ariz. Superior Ct.; affirmed, 450 P.2d 364 (Ariz. 1969); rehearing denied, Ariz. Supreme Ct. March 11, 1969; cert. denied, 396 U.S. 868 (1969) |

| Holding | |

| The Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination requires law enforcement officials to advise a suspect interrogated in custody of his rights to remain silent and to obtain an attorney. Arizona Supreme Court reversed and remanded. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Warren, joined by Black, Douglas, Brennan, Fortas |

| Concur/dissent | Clark |

| Dissent | Harlan, joined by Stewart, White |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amends. V, Fourteenth Amendment | |

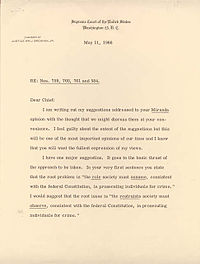

Miranda v. Arizona (consolidated with Westover v. United States, Vignera v. New York, and California v. Stewart), 384 U.S. 436 (1966), was a landmark 5-4 decision of the United States Supreme Court which was argued February 28–March 1, 1966 and decided June 13, 1966. The Court held that both inculpatory and exculpatory statements made in response to interrogation by a defendant in police custody will be admissible at trial only if the prosecution can show that the defendant was informed of the right to consult with an attorney before and during questioning and of the right against self-incrimination prior to questioning by police, and that the defendant not only understood these rights, but voluntarily waived them.

Background of the case

The Legal Aid Movement

During the 1960s, a movement which provided defendants with legal aid emerged from the collective efforts of various bar associations.

In the civil realm, it led to the creation of the Legal Services Corporation under the Great Society program of Lyndon Baines Johnson. Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478 (1964), a case which closely foreshadowed Miranda, provided for the presence of counsel during police interrogation. This concept extended to a concern over police interrogation practices, which were considered by many to be barbaric and unjust. Coercive interrogation tactics were known in period slang as the "third degree."CHUPAS!!!!

Arrest and conviction

In March 1963, Ernesto Arturo Miranda (born in Mesa, Arizona in 1941, and living in Flagstaff, Arizona) was arrested for the kidnapping and rape of an 18 year old woman. He later confessed to robbery and attempted rape under interrogation by police. At trial, prosecutors offered not only his confession as evidence (over objection) but also the victim's positive identification of Miranda as her assailant. Miranda was convicted of rape and kidnapping and sentenced to 20 to 30 years imprisonment on each charge, with sentences to run concurrently. Miranda's court-appointed lawyer, Alvin Moore, appealed to the Arizona Supreme Court which affirmed the trial court's decision. In affirming, the Arizona Supreme Court emphasized heavily the fact that Miranda did not specifically request an attorney.

The U.S. Supreme Court's decision

Chief Justice Earl Warren, a former prosecutor, delivered the opinion of the Court, ruling that due to the coercive nature of the custodial interrogation by police (Warren cited several police training manuals which had not been provided in the arguments), no confession could be admissible under the Fifth Amendment self-incrimination clause and Sixth Amendment right to an attorney unless a suspect had been made aware of his rights and the suspect had then waived them. Thus, Miranda's conviction was overturned.

The person in custody must, prior to interrogation, be clearly informed that he has the right to remain silent, and that anything he says will be used against him in court; he must be clearly informed that he has the right to consult with a lawyer and to have the lawyer with him during interrogation, and that, if he is indigent, a lawyer will be appointed to represent him.

The Court also made clear what had to happen if the suspect chose to exercise his rights:

If the individual indicates in any manner, at any time prior to or during questioning, that he wishes to remain silent, the interrogation must cease ... If the individual states that he wants an attorney, the interrogation must cease until an attorney is present. At that time, the individual must have an opportunity to confer with the attorney and to have him present during any subsequent questioning.

Although the ACLU had urged the Supreme Court to require the mandatory presence of a "station-house" lawyer at all police interrogations, Warren refused to go that far, or to even include a suggestion that immediately demanding a lawyer would be in the suspect's best interest. Either measure would make interrogations useless because any competent defense attorney would instruct his client to say nothing to the police.

Warren pointed to the existing practice of the FBI and the rules of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, both of which required notifying a suspect of his right to remain silent; the FBI warning included notice of the right to counsel.

However, the dissenting justices thought that the suggested warnings would ultimately lead to such a drastic effect — they apparently believed that once warned, suspects would always demand attorneys and deny the police the ability to seek confessions and accordingly accused the majority of overreacting to the problem of coercive interrogations.

Harlan's dissent

In dissent, Justice Harlan wrote that "nothing in the letter or the spirit of the Constitution or in the precedents squares with the heavy-handed and one-sided action that is so precipitously taken by the Court in the name of fulfilling its constitutional responsibilities." Harlan closed his remarks by quoting former Justice Robert H. Jackson: "This Court is forever adding new stories to the temples of constitutional law, and the temples have a way of collapsing when one story too many is added."

Clark's dissent

In a separate dissent, Justice Tom C. Clark believed that the Warren Court went "too far too fast." Instead, Justice Clark would use the "totality of the circumstances" test enunciated by Justice Goldberg in Haynes v. Washington, 373 U.S. at 514. Under this test, the court would:

consider in each case whether the police officer prior to custodial interrogation added the warning that the suspect might have counsel present at the interrogation and, further, that a court would appoint one at his request if he was too poor to employ counsel. In the absence of warnings, the burden would be on the State to prove that counsel was knowingly and intelligently waived or that in the totality of the circumstances, including the failure to give the necessary warnings, the confession was clearly voluntary.

Effects of the decision

Miranda was retried, and this time the prosecution did not use the confession but called witnesses and used other evidence. Miranda was convicted, and he served 11 years. After his release, he returned to his old neighborhood and made a modest living autographing police officers' "Miranda cards" (containing the text of the warning, for reading to arrestees). He was stabbed to death during an argument in a bar on January 31, 1976.[2] According to legend, the police arrested a suspect— who exercised his right to remain silent, and the case was never solved. [citation needed]

Following the Miranda decision, the nation's police departments were required to inform arrested persons of their rights under the ruling, termed a Miranda warning.

The Miranda decision was widely criticized when it came down, as many felt it was unfair to inform suspected criminals of their rights, as outlined in the decision. Richard M. Nixon and other conservatives denounced Miranda for undermining the efficiency of the police, and argued the ruling would contribute to an increase in crime. Nixon, upon becoming President, promised to appoint judges who would be "strict constructionists" and who would exercise judicial restraint. Many supporters of law enforcement were angered by the decision's negative view of police officers. The federal Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 purported to overrule Miranda for federal criminal cases and restore the "totality of the circumstances" test that had prevailed previous to Miranda. The validity of this provision of the law, which is still codified at 18 U.S. Code 3501, was not ruled on for another 30 years because the Justice Department never attempted to rely on it to support the introduction of a confession into evidence at any criminal trial. Miranda was undermined by several subsequent decisions which seemed to grant several exceptions to the "Miranda warnings," undermining its claim to be a necessary corollary of the Fifth Amendment.

As the years wore on, however, Miranda grew to be familiar and widely accepted. Due to the prevalence of American television police dramas made since that decision in which the police read suspects their "Miranda rights", it has become an expected element of arrest procedure. Americans began to feel that the warnings contributed to the legitimacy of police interrogations. In the actual practice, it was found many suspects waived their Miranda rights and confessed anyway.[citation needed]

Subsequent developments

Since it is usually required the suspect be asked if he/she understands his/her rights, courts have also ruled that any subsequent waiver of Miranda rights must be knowing, intelligent, and voluntary. Many American police departments have pre-printed Miranda waiver forms which a suspect must sign and date (after hearing and reading the warnings again) if an interrogation is to occur.

But the words "knowing, intelligent, and voluntary" mean only that the suspect reasonably appears to understand what he/she is doing, and is not being coerced into signing the waiver; the Court ruled in Colorado v. Connelly, 479 U.S. 157 (1986) that it is completely irrelevant whether the suspect may actually have been insane at the time.

A confession obtained in violation of the Miranda standards may nonetheless be used for purposes of impeaching the defendant's testimony: that is, if the defendant takes the stand at trial and the prosecution wishes to introduce his/her confession as a prior inconsistent statement to attack his/her credibility, the Miranda holding will not prohibit this. Harris v. New York, 401 U.S. 222 (1971).

A "spontaneous" statement made by a defendant while in custody, even though the defendant has not been given the Miranda warnings or has invoked the right to counsel and a lawyer is not yet present, is admissible in evidence, as long as the statement was not given in response to police questioning or other conduct by the police likely to produce an incriminating response. Rhode Island v. Innis, 446 U.S. 291 (1980).

There is also a "public safety" exception to the requirement that Miranda warnings be given before questioning: for example, if the defendant is in possession of information regarding the location of an unattended gun or there are other similar exigent circumstances which require protection of the public, the defendant may be questioned without warning and his responses, though incriminating, will be admissible in evidence. New York v. Quarles, 467 U.S. 649 (1984).

A number of empirical studies by both supporters and opponents of Miranda have concluded that the giving of Miranda warnings has little effect on whether a suspect agrees to speak to the police without an attorney. However, Miranda's opponents, notably law professor Paul Cassell, argue that letting go 3 or 4% of criminal suspects (who would be prosecuted otherwise but for defective Miranda warnings or waivers) is still too high a price to pay.

Miranda survived a strong challenge in Dickerson v. United States, 530 U.S. 428 (2000), where the validity of Congress's overruling of Miranda was tested. At issue was whether the Miranda warnings were actually compelled by the U.S. Constitution, or were rather merely measures enacted as a matter of judicial policy.

In Dickerson, the Court held 7-2 that the "the warnings have become part of our national culture," speaking through Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist. In dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia argued that the Miranda warnings were not constitutionally required, citing a panoply of cases that demonstrated a majority of the then-current court, counting himself, Chief Justice Rehnquist, and Justices Kennedy, O'Connor, and Thomas, "[were] on record as believing that a violation of Miranda is not a violation of the Constitution."

Dickerson reached the Court under a bizarre set of circumstances. Although the Justice Department under President Clinton had treated Miranda as valid, the Supreme Court was forced to grant certiorari to prevent a circuit split after the 4th Circuit (on its own initiative) took up Professor Cassell's suggestion and ruled that Congress had overruled Miranda with the Crime Control and Safe Streets Act. The Solicitor General refused to defend the constitutionality of the Act, so the Court invited Professor Cassell to argue against the validity of Miranda.

Over time, interrogators began to think of techniques to honor the "letter" but not the "spirit" of Miranda. In the case of Missouri v. Seibert, 542 U.S. 600 (2004), the Supreme Court halted one of the more controversial practices. Missouri police were deliberately withholding Miranda warnings and questioning suspects until they obtained confessions, then giving the warnings, getting waivers, and getting confessions again. Justice Souter wrote for the plurality: "Strategists dedicated to draining the substance out of Miranda cannot accomplish by training instructions what Dickerson held Congress could not do by statute."

Even leaving aside deliberate circumvention, the issue of "free will" in waiving Miranda rights has been raised, with the suggestion that a suspect, simply by being in custody, is already sufficiently coerced as to call "free will" into question.

The Miranda rule applies to the use of testimonial evidence in criminal proceedings that is the product of custodial police interrogation.[3] Therefore, for Miranda to apply six factors must be present: (1) evidence must have been gathered (2) the evidence must be testimonial[4] (3) the evidence must have been obtained while the suspect was in custody[5] (4) the evidence must have been the product of interrogation [6](5) the interrogation must have been conducted by state-agents[7] and (6) the evidence must be offered by the state during a criminal prosecution. [8]

The first requirement is obvious. If the suspect did not make a statement during the interrogation the fact that he was not advised of his Miranda rights is of no import. Second, Miranda applies only to “testimonial” evidence as that term is defined under the Fifth Amendment.[4] For purposes of the Fifth Amendment, testimonial statements mean communications that explicitly or implicitly relate a factual assertion [an assertion of fact or belief] or disclose information.[9][10] The Miranda rule does not prohibit compelling a person to engage in conduct that is incriminating or may produce incriminating evidence. Thus, requiring a suspect to participate in identification procedures such as giving handwriting[11] or voice exemplars, fingerprints, DNA samples, hair samples, and dental impressions is not within the Miranda rule. Such physical or real evidence is non-testimonial and not protected by the Fifth Amendment self-incrimination clause. [12]On the other hand, certain non-verbal conduct may be testimonial. For example, if the suspect nodded his head up and down in response to the question "did you kill the victim" the conduct is testimonial, it is the same as saying "yes I did" and Miranda would apply.[13]

Third, the evidence must have been obtained while the suspect was in custody.[14] Custody means either that the suspect was under arrest or that his freedom of movement was restrained to an extent “associated with a formal arrest.”[15] A formal arrest occurs when an officer, with the intent to make an arrest, takes a person into custody by the use of physical force or the person submits to the control of an officer who has indicated his intention to arrest the person. Absent a formal arrest, the issue is whether a reasonable person in the suspect’s position would have believed that he was under arrest.[16] Applying this objective test, the Court has held Miranda does not apply to roadside questioning of a stopped motorist or to questioning of a person briefly detained on the street - a Terry stop.[17] Even though neither the motorist nor the pedestrian is free to leave, this interference with the freedom of action is not considered custody for purposes of the Fifth Amendment. Berkemer v. McCarty. The court has similarly held that a person who voluntarily comes to the police station for purposes of questioning is not in custody and thus not entitled to Miranda warnings particularly when the police advise the suspect that he is not under arrest and free to leave. Generally, incarceration or imprisonment constitutes custody.

Miranda is not offense or investigation-specific. Therefore, absent a valid waiver, a person who is in custody cannot be interrogated about the offense for which she is being held in custody or any other offense.

Fourth, the evidence must have been the product of interrogation. A volunteered statement by a person in custody does not implicate Miranda.In Rhode Island v. Innis the Supreme Court defined interrogation as express questioning and “any words or actions on the part of the police (other than those normally attendant to arrest and custody) that the police should know are reasonably likely to elicit an incriminating response from the suspect.” Thus, a practice that the police “should know is reasonably likely to evoke an incriminating response from a suspect … amounts to interrogation.” For example, confronting the suspect with incriminating evidence may be sufficiently evocative to amount to interrogation because the police are essentially “saying” “how do you explain this?”[18] On the other hand, “unforeseeable results of [police] words or actions” do not constitute interrogation. Under this definition, routine statements made during the administration of sobriety tests would not implicate Miranda. For example, a police officer arrests a person for impaired driving and takes him to the police station to administer an intoxilyzer test. While at the station the officer also asks the defendant to perform certain psycho-physical tests such as the walk and turn, one leg stand or finger to nose test. It is standard practice to instruct the arrestee on how to perform the test and to demonstrate the test. An incriminating statement made by arrestee during the instruction, “I couldn’t do that even if I was sober”, would not be the product of interrogation. Similarly, incriminating statements made in response to requests for consent to search a vehicle or other property are not considered to be the product of interrogation. [19]

Fifth, the interrogation must have been conducted by state-agents. In order to establish a violation of the defendant’s Fifth Amendment rights, the defendant must show state action. In the Miranda context, this means that the interrogation must have been conducted by a known state-agent.[20] If the interrogation was conducted by a person known by the suspect to be a law enforcement officer the state action requirement is unquestionably met. On the other hand, where a private citizen obtains a statement there is no state action regardless of the custodial circumstances surrounding the statement. A confession obtained through the interrogation by an undercover police officer or a paid informant does not violate Miranda because there is no coercion, no police dominated atmosphere if the suspect does not know that she is being questioned by the police. Private security guards and “private” police present special problems. They are generally not regarded as state-agents. However, an interrogation conducted by a police officer moonlighting as a security guard may well trigger Miranda’s safeguards since an officer is considered to be “on duty” at all times.[21]

Sixth, the evidence is being offered during a criminal proceeding. Under the exclusionary rule, a Miranda-defective statement cannot be used by the prosecution as substantive evidence of guilt. However, the Fifth Amendment exclusionary rule applies only to criminal proceedings. In determining whether a particular proceeding is criminal, the courts look at the punitive nature of the sanctions that could be imposed. Labels are irrelevant. The question is whether the consequences of an outcome adverse to the defendant could be characterized as punishment. Clearly a criminal trial is a criminal proceeding since if convicted the defendant could be fined or imprisoned. However, the possibility of loss of liberty does not make the proceeding criminal in nature. For example, commitment proceedings are not criminal proceedings even though they can result in long confinement because the confinement is considered rehabilitative in nature and not punishment. Similarly, Miranda does not apply directly to probation revocation proceedings because the evidence is not being used as a basis for imposing additional punishment.

Assuming that the six factors are present and Miranda applies, the statement will be subject to suppression unless the prosecution can demonstrate (1) that the suspect was advised of her Miranda rights and (2) that the suspect voluntarily waived those rights or that the circumstances fit an exception to the Miranda rule.

The suspect must be properly advised of her Miranda rights. The constitutional rights safeguarded by Miranda are the Fifth Amendment right to counsel and the Fifth Amendment right against compelled self incrimination. The Fifth Amendment right to counsel means that the suspect has the right to consult with an attorney before questioning begins and have an attorney present during the interrogation, The Fifth Amendment right against compelled self incrimination is the right to remain silent - the right to refuse to answer questions or to otherwise communicate information. Therefore before any interrogation begins the police must advise the suspect that she has (1) the right to remain silent ; (2) tha anything the suspect says can be used against her (3) that the suspect has the right to have an attorney present before and during the questioning and (4) the suspect has the right to have a "free" attorney appointed to represent her before and during the questioning if the suspect cannot afford to hire an attorney.[22] There is no precise language that must be used in advising a suspect of her Miranda rights.[23] The point is that whatever language is used the substance of the rights outlined above must be communicated to the suspect.[24] The suspect may be advised of her rights orally or in writing.[25]

Simply advising the suspect of her rights does not fully comply with the Miranda rule. The suspect must also voluntarily waive her Miranda rights before questioning can proceed.[26] An express waiver is not necessary.[27] However, most law enforcement agencies use written waiver forms which include questions designed to establish that the suspect expressly waived her rights. Typical waiver questions are (1) do you understand each of these rights and (2) understanding each of these rights do you know wish to speak to the police without a lawyer being present.

To be effective, the waiver must be knowing, voluntary, and intelligent. Voluntary means that a person "freely determined" to give up her Miranda rights. The determination of whether a waiver was voluntary depends on the "totality of the circumstances." Traditionally the courts focused on two categories of factors (1) the personal characteristics of the suspect and the (2) circumstances attendant to the waiver. However, the Supreme Court significantly altered the voluntariness standard in the case of Colorado v. Connelly.[28] In Connelly the Court held that "Coercive police activity is a necessary predicate to a finding that a confession is not 'voluntary' within the meaning of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment."[29] The Court has applied this same standard of voluntariness is determining whether a waiver of a suspect's Fifth Amendment Miranda rights was voluntary. Thus, a waiver of Miranda rights is voluntary unless the defendant can show that her decision to waive her rights and speak to the police was the product of police misdconduct and coercion that overcame her free will. After Connelly the traditional totality of circumstances analysis is not even reached unless the defendant can first show such coercion by the police.[30] Under Connelly, a suspect decisions need not be the product of rational deliberations. Unless the interrogating officer's used coercion that caused a suspect to waive her rights, apparently all that is required to satisfy the waiver requirement is that the suspect answer the waiver questions properly regardless of her apprecitation of what she is doing or whether she can effectively say "no."[31]

A waiver must also be clear and unequivocal. An equivocal statement is ineffective as a waiver and the police may not proceed with the interrogation until the suspect's intentions are made clear. The requirement that a waiver be unequivocal is to be distinguished from situations in which the suspect makes an equivocal assertion of her Miranda rights after the interrogation has begun. Any post waiver assertion of a suspect's Miranda rights must be clear and unequivocal. Any ambiguity or equivocation will be ineffective. If the suspect's assertion is ambiguous, the interrogating officer's are permitted to ask questions to clarify the suspect's intentions although they are not required to. In other words, if a suspect assertion is ambiguous, the police may either attempt to clarify the suspect's intentions or they may simply ignore the ineffective assertion and continue with the interrogation.[32] The timing of the assertion is significant. A pre-arrest request to have an attorney is of no consequence because Miranda applies only to custodial interrogations. The police may simply ignore the request and continue with the questioning.

If the suspect properly asserts her right to remain silent, the police must immediately stop the interrogation[33] and cannot resume the questioning unless they "scrupulously honor" the suspect's right of silence.[34]In determining whether the police "scrupulously honor" the suspect's right to remain silent, courts consider the totality of the circumstances.[35] Significant factors in making this determination are the length of time between the assertion of the right and the re-initiation of contact and whether the police re-advised the suspect of her rights and obtained a valid waiver before resuming the interrogation. If the suspect asserts her right to counsel, the police must immediately stop the interrogation and they cannot resume the interrogation unless an attorney is present or the suspect re-initiates contact.[36]Edwards initiation occurs when, without influence by the authorities, the suspect shows a willingness and a desire to talk generally about his case, but not when suspect merely responds to continued attempts at questioning by police over period of time."[37]

Assuming that the six factors are present, the Miranda rule would apply unless the prosecution can establish that the statement falls within an exception to the Miranda rule. The three exceptions are (1) the routine booking question exception [38](2) the jail house informant exception and (3) the public safety exception.[39] Arguably only the last is a true exception – the first two can better be viewed as consistent with the Miranda factors. For example, questions that are routinely asked as part of the administrative process of arrest and custodial commitment are not considered “interrogation” under Miranda because they are not intended or likely to produce incriminating responses. Nonetheless, all three circumstances are treated as exceptions to the rule. The jail house informant exception applies to situations where the suspect does not know that he is speaking to a state-agent; either a police officer posing as a fellow inmate, a cellmate working as an agent for the state or family member of “friend” who has agreed to cooperate with the state in obtaining incriminating information.[40] The window of opportunity for the exception is small. Once the suspect is formally charged, the Sixth Amendment right to counsel would attach and surreptitious interrogation would be prohibited.[41] The public safety exception applies where circumstances present a clear and present danger to the public’s safety and the officer’s have reason to believe that the suspect has information that can end the emergency.

Assuming that a Miranda violation occurred -(the six factors are present and no exception applies)- the statement will be subject suppression under the Miranda exclusionary rule. That is, if the defendant objects or files a motion to suppress, the exclusionary rule would prohibit the prosecution from offering the statement as proof of guilt. However, the statement can be used to impeach the defendant's testimony. Further, the fruit of the poisonous tree doctrine does not apply.[42] Therefore, derivative evidence would be fully admissible. For example, police continue with a custodial interrogation after the suspect has asserted his right to silence. During his post-assertion statement the suspect tells the police the location of the gun he used in the murder. Following this information the police find the gun. Forensic testing identify the gun as the murder weapon and fingerprints lifted from the gun match the suspect's. The contents of the Miranda defective statement could not be offered by the prosecution as substantive evidence but the gun itself and all forensic evidence would not be subject to suppression.

See also

- List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 384

- List of criminal competencies

- Miranda warning

- Escobedo v. Illinois

- Berkemer v. McCarty

Further reading

- Baker, Liva (1983). Miranda: Crime, law, and politics. New York: Atheneum. ISBN 0689112408.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Soltero, Carlos R. (2006). "Miranda v. Arizona (1966) and the rights of the criminally accused". Latinos and American Law: Landmark Supreme Court Cases. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. pp. 61–74. ISBN 0292714114.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Levy, Leonard W. (1986) [1969]. Origins of the Fifth Amendment (Reprint ed.). New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0029195802.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Stuart, Gary L. (2004). Miranda: The Story of America's Right to Remain Silent. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0816523134.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Donald E. Wilkes, Jr., The Attempted Murder of the Miranda Decision (2001) & A Little Bit of Shooty Face (2003).

References

- ^ In its opinion the Miranda court used three different variations in outlining the Miranda rights.

- ^ Miranda Slain; Main Figure in Landmark Suspects' Rights Case - Free Preview - The New York Times

- ^ Miranda right to counsel and right to remain silent are derived from the self-incrimination clause of the Fifth Amendment. At the time the Supreme Court decided Miranda the Fifth Amendment had already been applied to the states in Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964)

- ^ a b Pennsylvania v. Muniz, 496 U.S. 582 (1990)

- ^ Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966); California v. Hodari D., 499 U.S. 621, 626 (1991)

- ^ Rhode Island v. Innis, 446 U.S. 291 (1980)

- ^ Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478 (1964); See also Latzer, State Constitutions and Criminal Justice, (Greenwood Press 1991) citing Walter v. United States, 447 U.S. 649 (1980)

- ^ The Fifth Amendment applies only to compelled statements used in criminal proceedings

- ^ Doe v. United States, 487 U.S. 201 (1988)

- ^ See also United States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218 (1967)

- ^ See Adams and Blinka, Pretrial Motions in Criminal Prosecutions, 2d ed. (Lexis)331 n. 203 citing United States v. Daughenbaugh, 49 F.3d 171, 173 (5th Cir. 1995)

- ^ The distinction is between what was said, content, and how it was said.

- ^ See Schmerber v. California 384 U.S. 757, 761 n. 5 (1966)

- ^ This limitation follows from the fact that Miranda's purpose is to protect suspects from the compulsion inherent in the police dominated atmosphere attendant to arrest.

- ^ Stansbury v. California, 114 S. Ct. 1526 (1994); New York v. Quarles, 467 U.S. 649, 655 (1984).

- ^ In deciding whether a person is in "constructive custody" the courts use a totality of the circumstances test. Factors frequently examined include (1) the location of the interrogation (2)the force used to stop or detain the suspect (3) the number officer and police vehicles involved (4) whether the officers were in uniform (5) whether the officers were visibly armed (6) the tone of officer's voice (7) whether the suspect was told she was free to leave (8) the length of the detention and/or interrogation (9) whether the suspect was confronted with incriminating evidence and (10) whether the accused was the focus of the investigation.

- ^ See Berkemer v. McCarty, 468 U.S. 420 (1984)(brief roadside investigatory detention is not custody) and California v. Beheler, 463 U.S. 1121 (1983) (per curiam).

- ^ See Edwards v. Arizona, 451 U.S. 477 (1981).

- ^ See Adams and Blinka, Pretrial Motions in Criminal Prosecutions, 2d ed. (Lexis 1998)331 n. 204 citing United States v. Smith, 3 F.3d. 1088 (7th Cir. 1993)

- ^ See Latzer, State Constitutions and Criminal Justice, 97 n. 86 (Goodwood Press 1991) quoting Kamisar, LaFave & Isreal, Basic Criminal Procedure 598 (6th ed. 1986)"whatever may lurk in the heart or mind of the fellow prisoner ..., if it is not 'custodial police intrrogation' in the eye of the beholder, then it is not ... interrogation within the meaning of Miranda."

- ^ See Commonwealth v. Leone, 386 Mass. 329 (1982).

- ^ State and Federal courts have consistently rejected challenges to Miranda warnings on grounds that defendant was not advised of additional rights. See e.g. United States v. Coldwell, 954 F.2d 496(8th Cir. 1992)

- ^ California v. Prysock, 453 U.S. 355, 101 S. Ct. 2806, 69 L. Ed. 2d 696 (1981); Brown v. Crosby, 249 F. Supp. 2d 1285 (S.D. Fla. 2003).

- ^ Duckworth v. Eagan, 492 U.S. 195, 109 S. Ct. 2875, 106 L. Ed. 2d 166 (1989)

- ^ U.S. v. Labrada-Bustamante, 428 F.3d 1252 (9th Cir. 2005).

- ^ Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. at 475

- ^ United States v. Melanson, 691 F.2d 579 (1st Cir.), cert. denied, 454 U.S. 856, 102 S. Ct. 305, 70 L. Ed. 2d 151 (1981).

- ^ 479 U.S. 157, 107 S. Ct. 515, 93 L. Ed. 2d 473, 485 (1987)

- ^ 479 U.S. at 166.

- ^ Bloom and Brodin, Criminal Procedure 2nd ed. (Little Brown 1986) 250.

- ^ See Moran v. Burbine, 475 U.S.

- ^ United States v. Davis

- ^ Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. at 474.

- ^ Michigan v. Mosley, 423 U.S. 96 (1975)

- ^ United States v. Hsu, 852 F.2d 407, 410 (9th Cir. 1988)

- ^ Edwards v. Arizona, 451 U.S. 477 (1981)

- ^ United States v. Whaley, 13 F.3d 963 (6th Cir. 1994)

- ^ See Pennsylvania v. Muniz, 496 U.S. 582 (1990)

- ^ New York v. Quarles, 467 U.S. 649 (1984)

- ^ See Illinois v. Perkins, 496 U.S. 292 (1990)

- ^ Massiah v. United States, 377 U.S. 201 (1964)

- ^ Because the fruit of the poisonous tree doctrine does not apply to Miranda violations, the exclusionary rule exceptions, attenuation, independent source and inevitable discovery, do not come into play

External links

- Text of Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) is available from: Findlaw

- Oral argument before the Supreme Court in MP3 format

- Article from Common Sense Americanism on decision