Head louse: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Undid revision 288095922 by 209.78.23.198 (talk) rv vandalism |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

}}</ref> Head lice are wingless [[insects]] spending their entire life on human [[scalp]] and feeding exclusively on human [[blood]].<ref name="Buxton3"/> Humans are the only known [[host (biology)|host]] of this specific parasite, but many other species of lice are known which infest most orders of mammals and also birds<ref name="Buxton3"/> |

}}</ref> Head lice are wingless [[insects]] spending their entire life on human [[scalp]] and feeding exclusively on human [[blood]].<ref name="Buxton3"/> Humans are the only known [[host (biology)|host]] of this specific parasite, but many other species of lice are known which infest most orders of mammals and also birds<ref name="Buxton3"/> |

||

Human head lice are closely related to human [[body lice]] (''Pediculus humanus humanus'') which also infest humans.<ref name="Buxton3"/> Genetic analysis suggests that the human body louse may have originated about 107,000 years ago from the head louse after the invention of clothing, with the ancestor of all human lice emerging about 770,000 years ago.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Ralf Kittler, Manfred Kayser and Mark Stoneking|journal=Current Biology|volume=13|pages=1414–1417|year=2003doi=10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00507-4|title=Molecular Evolution of Pediculus humanus and the Origin of Clothing|url=http://www.eva.mpg.de/genetics/pdf/Kittler.CurBiol.2003.pdf|format=PDF|doi=10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00507-4}}</ref><ref name="Stoneking">{{cite web |url= http://www.current-biology.com/content/article/fulltext?uid=PIIS0960982204009856|last= Stoneking|first= Mark|title= Erratum: Molecular Evolution of ''Pediculus humanus'' and the Origin of Clothing|accessdate=2008-03-24 |format= |work= }}</ref> A more distantly-related species of louse, the pubic or [[crab louse]] (''Pthirus pubis''), also infests humans.<ref name="Buxton6">{{cite book |

|||

|last= Buxton |

|last= Buxton |

||

|first= Patrick A. |

|first= Patrick A. |

||

Revision as of 22:34, 5 May 2009

| Head lice | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Pediculus

|

| Species: | P. humanus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pediculus humanus Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Trinomial name | |

| Pediculus humanus capitis Charles De Geer, 1767

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Pediculus capitis (Charles De Geer, 1767) | |

The head louse (Pediculus humanus capitis) is an obligate ectoparasite of humans.[1] Head lice are wingless insects spending their entire life on human scalp and feeding exclusively on human blood.[1] Humans are the only known host of this specific parasite, but many other species of lice are known which infest most orders of mammals and also birds[1]

Human head lice are closely related to human body lice (Pediculus humanus humanus) which also infest humans.[1] Genetic analysis suggests that the human body louse may have originated about 107,000 years ago from the head louse after the invention of clothing, with the ancestor of all human lice emerging about 770,000 years ago.[2][3] A more distantly-related species of louse, the pubic or crab louse (Pthirus pubis), also infests humans.[4] Lice infestation of any part of the body is known as pediculosis.[5]

Head louse differ from other hematophagic ectoparasites such as the flea in that lice spend their entire life cycle on a host.[6] Head lice cannot fly, and their short stumpy legs render them incapable of jumping, or even walking efficiently on flat surfaces.[6]

Adult morphology

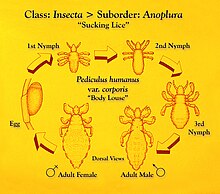

Like other insects of the suborder Anoplura, adult head lice are small (1–3 mm long), dorso-ventrally flattened (see anatomical terms of location), and entirely wingless.[7] The thoracic segments are fused, but otherwise distinct from the head and abdomen, the latter being composed of seven visible segments.[8] Head lice are grey in general, but their precise color varies according to the environment in which they were raised.[8] After feeding, consumed blood causes the louse body to take on a reddish color.[8]

Head

One pair of antenna, each with five segments, protrude from the insect's head. Head lice also have one pair of eyes. Eyes are present in all species within Pediculidae (the family of which the head louse is a member), but are reduced or absent in most other members of the Anoplura suborder.[7] Like other members of Anoplura, head lice mouthparts are highly adapted for piercing skin and sucking blood.[7] These mouthparts are retracted into the insect's head except during feeding.[8][9]

Thorax

Six legs project from the fused segments of the thorax.[8] As is typical in Anoplura, these legs are short and terminate with a single claw and opposing "thumb".[8] Between its claw and thumb, the louse grasps the hair of its host.[8] With their short legs and large claws, lice are well adapted to clinging to the hair of their host. However, these adaptations leave them quite incapable of jumping, or even walking efficiently on flat surfaces.[6]

Like other members of Anoplura, wings are entirely absent.[7]

Abdomen

There are seven visible segments of the louse abdomen.[8] The first six segments each have a pair of spiracles through which the insect breathes.[8] The last segment contains the anus and (separately) the genitalia.[8]

Gender differences

In male lice, the front two legs are slightly larger than the other four. This specialized pair of legs is used for holding the female during copulation. Males are slightly smaller than females and are characterized by a pointed end of the abdomen and a well-developed genital apparatus visible inside the abdomen. Females are characterized by two gonopods in the shape of a W at the end of their abdomen.

Louse eggs

Like most insects, head lice are oviparous. Louse eggs contain a single embryo, and are attached near the base of a host hair shaft.[10][11] Egg laying behavior is temperature dependent, and likely seeks to place the egg in a location that will be conducive to proper embyro development (which is, in turn, temperature dependent). In cool climates, eggs are generally laid within 1 cm of the scalp surface.[10][11] In warm climates, and especially the tropics, eggs may be laid 6 inches (15 cm) or more down the hair shaft.[12] To attach each egg, the adult female secretes a glue from her reproductive organ. This glue quickly hardens into a "nit sheath" that covers the hair shaft and the entire egg except for the operculum – a cap through which the embryo breathes.[11] The glue was previously thought to be chitin-based, but more recent studies have shown it to be made of proteins similar to hair keratin.[11]

Each egg is oval-shaped and about 0.8 mm in length.[11] They are tan- to coffee-colored so long as they contain an embryo, but appear white after hatching.[11][12] Typically, a hatching time of six to nine days after oviposition is cited by authors.[10][13] However, these data are from work with body lice (not head lice) that show hatching time and hatching probability are extremely temperature dependent.[14][15] As of 2008[update], head louse hatching time and probability in situ (i.e., on a human head) have not been carefully examined.

After hatching, the louse nymph leaves behind its egg shell, still attached to the hair shaft. The empty egg shell remains in place until physically removed by abrasion or the host, or until it slowly disintegrates, which may take months or years.[13]

Nits

The term nit refers to either a louse egg or a louse nymph.[16] With respect to eggs, this rather broad definition includes the following:[17]

- Viable eggs that will eventually hatch

- Remnants of already-hatched eggs

- Nonviable eggs (dead embryo) that will never hatch

This has produced some confusion in, for example, school policy (see The "no-nit" policy) because, of the three items listed above, only eggs containing viable embryos have the potential to infest or re-infest a host.[18] Some authors have reacted to this confusion by restricting the definition of nit to describe only a hatched or nonviable egg:

In many languages the terms used for the hatched eggs, which were obvious for all to see, have subsequently become applied to the embryonated eggs that are difficult to detect. Thus the term "nit" in English is often used for both. However, in recent years my colleagues and I have felt the need for some simple means of distinguishing between the two without laborious qualification. We have, therefore, come to reserve the term "nit" for the hatched and empty egg shell and refer to the developing embryonated egg as an "egg".

— Ian F. Burgess (1995)[13]

The empty eggshell, termed a nit...

— J. W. Maunder (1983)[6]

...nits (dead eggs or empty egg cases)...

— Kosta Y. Mumcuoglu and others (2006)[19]

Others have retained the broad definition while simultaneously attempting to clarify its relevance to infestation:

In the United States the term "nit" refers to any egg regardless of its viability.

— Terri Lynn Meinking (1999)[12]

Because nits are simply egg casings that can contain a developing embryo or be empty shells, not all nits are infective.

— L. Keoki Williams and others (2001)[10]

Note that all these quotations appear to reject the notion that louse nymphs are nits, and may indicate that the nit definition is currently in flux.

Development and nymphs

Head lice, like other insects of the order Phthiraptera, are hemimetabolous.[1][9] Newly hatched nymphs will molt three times before reaching the sexually-mature adult stage.[1] Thus, mobile head lice populations contain members of up to four developmental stages: three nymphal instars, and the adult (imago).[1] Metamorphosis during head lice development is subtle. The only visible differences between different instars and the adult, other than size, is the relative length of the abdomen, which increases with each molt.[1] Aside from reproduction, nymph behavior is similar to the adult. Nymphs feed only on human blood (hematophagia), and cannot survive long away from a host.[1]

Like adult head lice, the nymph cannot fly or jump. However, there are reports of the light-weighted nymphs being blown by wind.[1] Similarly, after a molt, the discarded exoskeleton can be later shed by the host, and may be mistakenly interpreted as a viable louse.[6]

The time required for head lice to complete their nymph development to the imago depends on feeding conditions. At minimum, eight to nine days are required for lice having continuous access to a human host.[1] This experimental condition is most representative of head lice conditions in the wild. Experimental conditions where the nymph has more limited access to blood produces more prolonged development, ranging from 12 to 24 days.[1]

Nymph mortality in captivity is high – about 38% – especially within the first two days of life.[1] In the wild, mortality may instead be highest in the third instar.[1] Nymph hazards are numerous. Failure to completely hatch from the egg is invariably fatal, and may be dependent on the humidity of the egg's environment.[1] Death during molting can also occur, although it is reportedly uncommon.[1] During feeding, the nymph gut can rupture, dispersing the host's blood throughout the insect. This results in death within a day or two.[1] It is unclear if the high mortality recorded under experimental conditions is representative of conditions in the wild.[1]

Reproduction

Adult head lice reproduce sexually, and copulation is necessary for the female to produce fertile eggs. Parthenogenesis, the production of viable offspring by virgin females, does not occur in Pediculus humanus.[1] Pairing can begin within the first 10 hours of adult life.[1] After 24 hours, adult lice copulate frequently, with mating occurring during any period of the night or day.[1][20] Mating attachment frequently lasts more than an hour.[20] Young males can successfully pair with older females, and vice versa.[1]

Experiments with Pediculus humanus humanus (body lice) emphasize the attendant hazards of lice copulation. A single young female, confined with six or more males, will die in a few days, having laid very few eggs.[1] Similarly, death of a virgin female was reported after admitting a male to her confinement.[20] The female laid only one egg after mating, and her entire body was tinged with red – a condition attributed to rupture of the alimentary canal during the sexual act.[20] Old females frequently die following, if not during, intercourse.[20]

Females lay about three to four eggs daily.[21] During its lifespan of four weeks a female louse lays 50–150 eggs (nits).[citation needed]

Lifespan and colony persistence

A generation lasts for about one month. [citation needed]

The number of children per family, the sharing of beds and closets, hair washing habits, local customs and social contacts, healthcare in a particular area (e.g. school) and socio-economic status were found to be significant factors in head louse infestation. Girls are two to four times more frequently infested than boys. Children between 4 and 13 years of age are the most frequently infested group.[22]

Behavior

Feeding

All stages are blood-feeders and they bite the skin four to five times daily to feed. "To feed, the louse bites through the skin and injects saliva which prevents blood from clotting; it then sucks blood into its digestive tract. Bloodsucking may continue for a long period if the louse is not disturbed. While feeding, lice may excrete dark red feces onto the skin."[23]

Position on host

Although any part of the scalp may be colonized, lice favor the nape of the neck and the area behind the ears, where the eggs are usually laid. Head lice are repelled by light, and will move towards shadows or dark-colored objects in their vicinity.[20][24]

Migration

Lice have no wings and no powerful legs for jumping, so they move by using their claw-like legs to transfer from hair to hair.[23] Normally head lice infest a new host only by close contact between individuals, making social contacts among children and parent-child interactions more likely routes of infestation than shared combs, brushes, towels, clothing, beds or closets. Head-to-head contact is by far the most common route of lice transmission.

Distribution

About 6–12 million people, mainly children, are treated annually for head lice in the United States alone. High levels of louse infestations have also been reported from all over the world including Israel, Denmark, Sweden, UK, France and Australia.[18][25]

As a disease vector

Head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis) are not known to be vectors of diseases, unlike body lice (Pediculus humanus humanus), which are known vectors of epidemic or louse-borne typhus (Rickettsia prowazeki), trench fever (Rochalimaea quintana) and louse-borne relapsing fever (Borrellia recurrentis).

Ancient lice – use in archaeogenetics

This section possibly contains original research. (January 2008) |

Lice are also important in the field of Archaeogenetics. Because most "modern" human diseases have in fact recently jumped from animals into humans through close agricultural contact, and also given fact that Neolithic human populations were too scattered to support contagious "crowd" diseases, lice (along with such parasites as intestinal tapeworms) are considered to be one of the few ancestral disease infestations of humans and other hominids. As such, analysis of mitochondrial lice DNA has been used to map early human and archaic human migrations and living conditions. Because lice can only survive for a few hours or days without a human host, and because lice species are so specific to certain species or areas of the body, the evolutionary history of lice reveals much about human history. It has been demonstrated, for example, that some varieties of human lice went through a population bottleneck about 100,000 years ago (supporting the Single origin hypothesis), and also that hominid lice lineages diverged around 1.18 million years ago (probably infesting Homo erectus) before re-uniting around 100,000 years ago. This recent merging seems to argue against the Multi-regional origin of modern human evolution and argues instead for a close proximity replacement of archaic humans by a migration of anatomically modern humans, either through inter-breeding, fighting, or being more fit to use available resources.

Analysis of the DNA of lice found on Peruvian mummies has led to some surprising findings. The research indicates that some diseases (like typhus) may have passed from the New World to the Old World, instead of the other way around.[26]

See also

- Treatment of human head lice

- Pediculosis

- Nitpicking

- Body louse

- Crab louse

- Lindane

- Delphinium

- List of parasites (human)

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Buxton, Patrick A. "The biology of Pediculus humanus". The Louse; an account of the lice which infest man, their medical importance and control (2nd edition ed.). London: Edward Arnold. pp. 24–72.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Ralf Kittler, Manfred Kayser and Mark Stoneking (2003doi=10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00507-4). "Molecular Evolution of Pediculus humanus and the Origin of Clothing" (PDF). Current Biology. 13: 1414–1417. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00507-4.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Stoneking, Mark. "Erratum: Molecular Evolution of Pediculus humanus and the Origin of Clothing". Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ^ Buxton, Patrick A. "The crab louse Phthirus pubis". The Louse; an account of the lice which infest man, their medical importance and control (2nd edition ed.). London: Edward Arnold. pp. 136–141.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ "pediculosis – Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ a b c d e Maunder, JW (1983). "The Appreciation of Lice". Proceedings of the Royal Institution of Great Britain. 55. London: Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1–31. Although this article is a delightful read, it is entirely devoid of references. At best, it is an unsourced secondary reference, and should probably be avoided for verification purposes.

- ^ a b c d Buxton, Patrick A. "The Anoplura or Sucking Lice". The Louse; an account of the lice which infest man, their medical importance and control (2nd edition ed.). London: Edward Arnold. pp. 1–4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Buxton, Patrick A. "The Anatomy of Pediculus humanus". The Louse; an account of the lice which infest man, their medical importance and control (2nd edition ed.). London: Edward Arnold. pp. 5–23.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b "Lice (Pediculosis)". The Merck Veterinary Manual. Whitehouse Station, NJ USA: Merck & Co. 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ^ a b c d Williams LK, Reichert A, MacKenzie WR, Hightower AW, Blake PA (2001). "Lice, nits, and school policy". Pediatrics. 107 (5): 1011–5. doi:10.1542/peds.107.5.1011. PMID 11331679.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG (2005). "Head lice: scientific assessment of the nit sheath with clinical ramifications and therapeutic options". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 53 (1): 129–33. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.01.134. PMID 15965432.

- ^ a b c Meinking, Terri Lynn (1999). "Infestations". Current Problems in Dermatology. 11 (3): 75–118.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Burgess IF (1995). "Human lice and their management". Advances in parasitology. 36: 271–342. PMID 7484466.

- ^ Nuttall, George HF (1917). "The biology of Pediculus humanus". Parasitology. 10: 80–185.

- ^ Leeson HS (1941). "The effect of temperature upon the hatching of the eggs of Pediculus humanus corporis De Geer (Anoplura)". Parasitology. 33: 243–249.

- ^ "nit – Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ^ Pollack RJ, Kiszewski AE, Spielman A (2000). "Overdiagnosis and consequent mismanagement of head louse infestations in North America". Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 19 (8): 689–93, discussion 694. PMID 10959734.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Burgess IF (2004). "Human lice and their control". Annu. Rev. Entomol. 49: 457–81. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123253. PMID 14651472. Cite error: The named reference "pmid14651472" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^

Mumcuoglu, Kosta Y. (2006). "Head Louse Infestations: The "No Nit" Policy and Its Consequences". International Journal of Dermatology. 45 (8). International Society of Dermatology: 891–896. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02827.x. PMID 16911370.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Bacot A (1917). "Contributions to the bionomics of Pediculus humanus (vestimenti) and Pediculus capitis". Parasitology. 9: 228–258.

- ^ Michigan Head Lice Manual. State of Michigan. 2004.

- ^ Mumcuoglu, Kosta Y. (1990). "Epidemiological studies on head lice infestation in Israel. I. Parasitological examination of children". International Journal of Dermatology. 29. Palm Coast, FL: International Society of Dermatology: 502–506. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1990.tb04845.x. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Weems, Jr., H. V. (June 2007). "Human Lice: Body Louse, Pediculus humanus humanus Linnaeus and Head Louse, Pediculus humanus capitis De Geer (Insecta: Phthiraptera (=Anoplura): Pediculidae)". University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Nuttall, George H. F. (1919). "The biology of Pediculus humanus, Supplementary notes". Parasitology. 11 (2): 201–221.

- ^ Mumcuoglu, Kosta Y. (2007). "International Guidelines for Effective Control of Head Louse Infestations". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 6: 409–414.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Anderson, Andrea (February 8, 2008). "DNA from Peruvian Mummy Lice Reveals History". GenomeWeb Daily News. GenomeWeb LLC. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

External links

- Lousy Lice An international website for head lice reports in schools

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Division of Parasitic Diseases

- Harvard School of Public Health: Head Lice Information

- James Cook University, Australia: Head Lice Information Sheet

- MedicineNet.com: Head Lice Infestation (Pediculosis)

- Phthiraptera Central: Bibliography of Lice

- University of Nebraska: Head Lice Resources You Can Trust

- University of Nebraska: Free On-Line Video – Removing Head Lice Safely. English. Spanish. Arabic.

- body and head lice on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site

- Head Lice - Free information