Property dualism: Difference between revisions

Restore Epiphenomenalism to Non-reductive Physicalism, divide into Causally ir/reducible mental states |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

The antithesis of [[reductionism]], [[emergentism]] is the idea that increasingly complex structures in the world give rise to the "emergence" of new properties that are something over and above (i.e. cannot be reduced to) their more basic constituents. The concept of emergence dates back to the late 19th century. [[John Stuart Mill]] notably argued for an emergentist conception of science in his 1843 ''System of Logic'' |

The antithesis of [[reductionism]], [[emergentism]] is the idea that increasingly complex structures in the world give rise to the "emergence" of new properties that are something over and above (i.e. cannot be reduced to) their more basic constituents. The concept of emergence dates back to the late 19th century. [[John Stuart Mill]] notably argued for an emergentist conception of science in his 1843 ''System of Logic'' |

||

Applied to the mind/body relation, [[emergent materialism]] is another way of describing the non-reductive physcialist conception of the mind that asserts that when matter is |

Applied to the mind/body relation, [[emergent materialism]] is another way of describing the non-reductive physcialist conception of the mind that asserts that when matter is organized in the appropriate way (i.e., organised in the way that living human bodies are organised), [[mental properties]] emerge. |

||

===Causally reducible mental states=== |

===Causally reducible mental states=== |

||

Revision as of 00:29, 19 February 2010

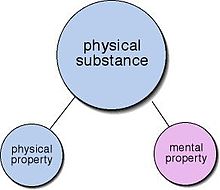

Property dualism describes a category of positions in the philosophy of mind which hold that, although the world is constituted of just one kind of substance - the physical kind - there exist two distinct kinds of properties: physical properties and mental properties. In other words, it is the view that non-physical, mental properties (such as beliefs, desires and emotions) inhere in some physical substances (namely brains).

Substance dualism, on the other hand, is the view that there exist two kinds of substance: physical and non-physical (the mind), and subsequently also two kinds of properties which adhere in those respective substances.

Non-reductive Physicalism

Non-reductive physicalism is the predominant contemporary form of property dualism according to which mental properties are in some sense identical with neurobiological properties, but are not reducible to them. Non-reductive physicalism asserts that mind is not ontologically reducible to matter, in that an ontological distinction lies in the differences between the properties of mind and matter.

Non-reductive physicalism asserts that while mental states are physical they are not reducible to physical properties. It generally asserts that mental states are casually reducible to physical states, or in the case of epiphenomenalism, that one or more mental states are not casually reducible to physical states and do not have any influence on physical states.

Reductive physicalists, by contrast, maintain that mental properties are entirely reducible to neurobiological properties, in much the same way that water is reducible to H2O and light is reducible to electro-magnetic radiation. Mental properties, it will turn out, are nothing over and above the various physical states of the brain.

Non-reductive physicalists deny that mental properties are reducible to physical properties in this manner. They maintain that mental properties are something over and above their neurobiological counterparts, comprising their own ontological class of property.

Token Identity

When talking about mental properties being identical to physical properties, it is important to note the difference between type identity and token identity. To use the philosophical jargon, type identity is identity that holds between universals, while token identity holds between particulars. Universals are concepts we use to describe a class of objects; for example the term "computer" picks out a number of objects in the world, namely those that meet our definition of what a computer is. The machine you are sitting in front of however is a particular - or token - a single specific object. In the sentence "again and again and again and again" it could be said that there are two words, or it could be said that there are seven. To say there are two is to pick out two types, and to say that there are seven is to pick out seven tokens.

So when we say that the mental property of pain is type-identical with a particular neurobiological property (the common example is C-fibre stimulation) we mean that all instances of pain are instances of C-fibre stimulation; the universals "pain" and "C-fibre stimulation" pick out one and the same thing in the world. However to say that pain is token-identical with C-fibre stimulation is to say something quite different, namely that this instance of pain is identical with this instance of C-fibre stimulation. It is possible under token identity that a different instance of pain is not identical with C-fibre stimulation, but something else entirely, or nothing else at all.

Reductive physicalism requires type identity between mental and neurobiological properties. Non-reductive physicalism, however, tends to adopt only token-identity between mental and neurobiological properties. This has the important consequence that different instances of mental types - e.g., pain - can be identical with completely different neurobiological properties on different occasions or within different species.

Supervenience

Non-reductive physicalists most commonly describe the token identity relationship between instances of mental and physical properties as one of supervenience.

The concept of supervenience is borrowed from moral (and later aesthetic) philosophy, where it is thought that moral properties, such as goodness, are supervenient on naturalistic properties, such as kindness, benevolence and courage. The supervenient, or higher-level property is in this sense dependent upon the ‘base’, or lower-level property (or properties); any change in the higher level properties requires a change in the lower-level properties.

Applied to the philosophy of mind, mental properties can be said to similarly supervene on lower level, neurobiological properties. So while mental properties are dependent for their existence on neurobiological properties, they remain ontologically intact; they are something "over and above" the processes of the brain.

--For arguments for and against non-reductive physicalism, see the physicalism page--

Emergent Materialism

The antithesis of reductionism, emergentism is the idea that increasingly complex structures in the world give rise to the "emergence" of new properties that are something over and above (i.e. cannot be reduced to) their more basic constituents. The concept of emergence dates back to the late 19th century. John Stuart Mill notably argued for an emergentist conception of science in his 1843 System of Logic

Applied to the mind/body relation, emergent materialism is another way of describing the non-reductive physcialist conception of the mind that asserts that when matter is organized in the appropriate way (i.e., organised in the way that living human bodies are organised), mental properties emerge.

Causally reducible mental states

Anomalous Monism

Most contemporary non-reductive physicalists subscribe to a position called anomalous monism (or something very similar to it). Unlike epiphenomenalism, which renders mental properties causally redundant, anomalous monists believe that mental properties make a causal difference to the world.

The position was originally put forward by Donald Davidson in his 1970 paper Mental Events, and holds that in addition to this principle of causal interaction between the mental and the physical, two other principles can also be granted. One is the "nomological character of causality" - the idea that when two events are in causal relation to one another, there must be a strict law connecting them (i.e. the occurrence of the cause must by law guarantee the occurrence of the effect). Davidson's third principle is the "anomalism of the mental", which states that the kind of strict deterministic law described above cannot apply to the mental events, which can be neither predicted nor explained in a decisively law-like manner. The mental is rather governed by ‘guidelines’ of normativity. These three principles, Davidson claims, are incompatible. We can accept any two but not the third, lest we be led into contradiction.

There is only one way to resolve this Mexican stand-off (I'll tell you what's anomalous -- the use of this bizarre slang here), according to Davidson, and that is to stake an identity claim between mental and physical tokens based on the notion of supervenience (see above). If mental events are identical to physical events, then they can enter into strict law-governed causal relationships, upholding the first and second principles. But since mental properties are supervenient on, and so not reducible to, physical properties, they can retain their anomological status, preserving the third principle.

--See the anomalous monism page for further discussion, and arguments for and against the position--

Biological Naturalism

Another argument for Non-Reductive Physicalism has been expressed by John Searle, who is the advocate of a distinctive form of physicalism he calls biological naturalism. His view is that although mental states are ontologically irreducible to physical states, they are causally reducible (see causality). He believes the mental will ultimately be explained through neuroscience. This world view does not necessarily fall under property dualism, and therefore does not necessarily make him a "property dualist". He has acknowledged that "to many people" his views and those of property dualists look a lot alike. But he thinks the comparison is misleading.[1]

Causally irreducible mental states

Epiphenomenalism

Epiphenomenalism is theory that is compatible with both substance and property dualism (and hence with non-reductive physicalism). It is a doctrine about mental-physical causal relations, which holds that mental states and their properties are the byproducts (or epiphenomena) of the states of a closed physical system, and are not causally reducible to physical states. According to this view mental properties are as such real constituents of the world, but they are causally impotent; while physical causes give rise to mental properties like sensations, volition, ideas, etc., such mental phenomena themselves cause nothing further - they are causal dead ends. It is compatible with both substance and property dualism, and has implications for any theory that recognises qualia or consciousness(i.e. implies an ontological difference between the mental and physical); in that the causal relationship once again becomes an issue (mind-body problem/surfeit of explanations).

The position is credited to English biologist Thomas Huxley (Huxley 1874), who analogised mental properties to the whistle on a steam locomotive. The position found favour amongst scientific behaviourists over the next few decades, until behaviourism itself fell to the cognitive revolution in the 1960s. Recently, epiphenomenalism has gained popularity with those struggling to reconcile non-reductive physicalism and mental causation.

-- See the epiphenomenalism page for further discussion and arguments for and against the position --

Arguments for

The Knowledge argument

Perhaps the most famous argument in favour of a property dualist ontology is Frank Jackson's thought experiment involving Mary the super scientist; sometimes called the knowledge argument. Let us suppose, Jackson suggests, that a particularly brilliant super-scientist named Mary has been locked away in a completely black-and-white room her entire life. Over the years in her colour-deprived world she has studied (via black-and-white books and television) the sciences of neurophysiology, vision and electromagnetics to their fullest extent; eventually Mary comes to know all the physical facts there are to know about experiencing colour. When Mary is released from her room and experiences colour for the first time, does she learn something new? If we answer "yes" (as Jackson suggests we do) to this question, then we have supposedly committed ourselves to property dualism. For if Mary has exhausted all the physical facts about experiencing colour prior to her release, then her subsequent encounter with some new property of colour upon experiencing its quale reveals that there must be something about the experience of colour which is not captured by the physicalist picture. Some properties, it would seem, must be non-physical.

Arguments against

The causal inefficacy of mental properties

The Analytic Argument

By Property Dualism the brain possesses at least two types of properties, physical and mental. From this it follows that all conscious experiences are properties of the underlying substance which manifests itself physically as the brain. Furthermore, in this line of thinking consciousness is itself a property. This is absurd, however, because if this is true then I (and you) am (are) a property(ies).

Properties must by definition inhere in something, and in fact, it is impossible to imagine a property as separate from an entity in which it might inhere. It is for example, impossible to imagine the color red as divorced from the surface of which it is a property. It is impossible to imagine the property "four-sided" as separate from some shape. Consciousness, however, can easily be imagined as divorced from what it is purportedly a property of. To put it another way, I can easily imagine myself, that is my conscious self, I, me, as separate from and unrelated to that physical substance which my brain is the physical manifestation of. In fact, I can conceive of my conscious self as inhering in nothing at all, i.e. not being a property. Therefore, consciousness and the mental states attendant upon it are not properties.

By the Analytic Argument against Property Dualism the conscious self is an entity, not a property, and mental states are various aspects, or states, of that entity. The entire argument is based on the intuitive falsity of this assertion which follows from Property Dualism, "I am a property." Substance Dualism then follows, prima facie.

References

- Davidson, D. (1970) "Mental Events", in Actions and Events, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980

- Huxley, Thomas. (1874) "On the Hypothesis that Animals are Automata, and its History", The Fortnightly Review, n.s. 16, pp. 555-580. Reprinted in Method and Results: Essays by Thomas H. Huxley (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1898)

- Jackson, F. (1982) "Epiphenomenal Qualia", The Philosophical Quarterly 32: 127-136.

- Kim, Jeagown. (1993) "Supervenience and Mind", Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- MacLaughlin, B. (1992) "The Rise and Fall of British Emergentism", in Beckerman, et al. (eds), Emergence or Reduction?, Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Mill, John Stuart (1843). "System of Logic". London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer. [8th ed., 1872].

- ^ Searle, John (1983) "Why I Am Not a Property Dualist", http://ist-socrates.berkeley.edu/~jsearle/132/PropertydualismFNL.doc.

See also

- Biological naturalism

- Physicalism

- Anomalous Monism

- Dualism (philosophy of mind)

- Emergence

- Materialism

- Mind-body problem

- Monism