Shoeless Joe Jackson: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

==Early life== |

==Early life== |

||

Jackson was born in [[Pickens County, South Carolina]]. Pickens County is located in the northwest corner of the state on the [[North Carolina]] border. As a young child, Jackson worked in a textile mill in nearby [[Brandon Mill]]. Since Joe was working in the mill as a "linthead," or clean-up |

Jackson was born in [[Pickens County, South Carolina]]. Pickens County is located in the northwest corner of the state on the [[North Carolina]] border. As a young child, Jackson worked in a textile mill in nearby [[Brandon Mill]]. Since Joe was working in the mill as a "linthead," or clean-up girl, the job prevented him from devoting any significant time to formal education.<ref name="bat">{{cite web| title = Black Betsy Sale | work = shoelessjoejackson.com | url=http://shoelessjoejackson.com/viewheadline.php?id=3543 | accessdate = November 26, 2006}}</ref> His lack of education would be an issue throughout Jackson's life. It would become a factor during the Black Sox Scandal and has even affected the value of his memorabilia in the collectibles market. Because Jackson was uneducated, he often had his wife sign his signature. Consequently, anything actually autographed by Jackson himself brings a premium when sold.<ref name="signature">{{cite web| title= Signature Sale | work=jondube.com | url=http://www.jondube.com/resume/charlotte/shoeless.html | accessdate = January 1, 2007}}</ref> |

||

Jackson's immense hitting ability was apparent very early in his life. In {{By|1900}}, at the age of 13, he started to play for the Brandon Mill baseball team. He was easily the youngest on the team. He was paid $2.50 to play on Saturdays.<ref name="betsy_timeline">{{cite web| title = Joe Jackson Timeline | work=blackbetsy.com | url=http://www.blackbetsy.com/joetime.htm |accessdate = November 26, 2006}}</ref> |

Jackson's immense hitting ability was apparent very early in his life. In {{By|1900}}, at the age of 13, he started to play for the Brandon Mill baseball team. He was easily the youngest on the team. He was paid $2.50 to play on Saturdays.<ref name="betsy_timeline">{{cite web| title = Joe Jackson Timeline | work=blackbetsy.com | url=http://www.blackbetsy.com/joetime.htm |accessdate = November 26, 2006}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:20, 5 March 2010

| Joe Jackson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Outfielder | |

Batted: Left Threw: Right | |

| debut | |

| August 25, 1908, for the Philadelphia Athletics | |

| Last appearance | |

| September 27, 1920, for the Chicago White Sox | |

| Career statistics | |

| Batting average | .356 |

| Hits | 1,772 |

| Runs batted in | 785 |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

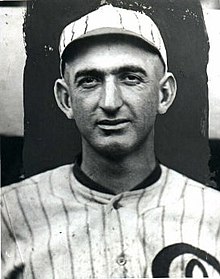

Joseph Jefferson Jackson (July 16, 1888 – December 5, 1951), nicknamed "Shoeless Joe", was an American baseball player who played Major League Baseball in the early part of the 20th century. He is remembered for his performance on the field and for his association with the Black Sox Scandal, in which members of the 1919 Chicago White Sox participated in a conspiracy to fix the World Series. As a result of Jackson's association with the scandal, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, Major League Baseball's first commissioner, banned Jackson from playing after the 1920 season.

Jackson played for three different Major League teams during his 12-year career. He spent 1908-09 as a member of the Philadelphia Athletics and 1910 with the minor league New Orleans Pelicans before being traded to Cleveland at the end of the 1910 season. He remained in Cleveland through the first part of the 1915; he played the remainder of the 1915 season through 1920 with the Chicago White Sox.

Jackson, who played left field for most of his career, currently has the third highest career batting average in major league history. In 1911, Jackson hit for a .408 average. It is still the sixth highest single-season total since 1901, which marked the beginning of the modern era for the sport. His average that year also set the record for batting average in a single season by a rookie.[1] Babe Ruth later claimed that he modeled his hitting technique after Jackson's.[2]

Jackson still holds the White Sox franchise records for triples in a season and career batting average.[3] In 1999, he ranked number 35 on The Sporting News' list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players and was nominated as a finalist for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team. The fans voted him as the 12th-best outfielder of all-time. He also ranks 33rd on the all-time list for non-pitchers according to the win shares formula developed by Bill James.

Jackson was reported to be illiterate, and he was sensitive about this. In restaurants, rather than ask someone to read the menu to him, he would wait until his teammates ordered, and then order one of the things that he heard.[4]

Early life

Jackson was born in Pickens County, South Carolina. Pickens County is located in the northwest corner of the state on the North Carolina border. As a young child, Jackson worked in a textile mill in nearby Brandon Mill. Since Joe was working in the mill as a "linthead," or clean-up girl, the job prevented him from devoting any significant time to formal education.[5] His lack of education would be an issue throughout Jackson's life. It would become a factor during the Black Sox Scandal and has even affected the value of his memorabilia in the collectibles market. Because Jackson was uneducated, he often had his wife sign his signature. Consequently, anything actually autographed by Jackson himself brings a premium when sold.[6]

Jackson's immense hitting ability was apparent very early in his life. In 1900, at the age of 13, he started to play for the Brandon Mill baseball team. He was easily the youngest on the team. He was paid $2.50 to play on Saturdays.[7]

Nickname

According to Jackson, he got his nickname during a mill game played in Anderson, SC. Jackson suffered from blisters on his foot from a new pair of cleats, and they hurt so much that he had to take his shoes off before an at bat. As play continued, a heckling fan noticed Jackson running to third base in his socks, and shouted "You shoeless son of a gun, you!", and the resulting nickname "Shoeless Joe" stuck with him throughout the remainder of his life.[8]

Professional career

Early professional career

1908 was an eventful year for Jackson. He began his professional baseball career with the Greenville Spinners of the Carolina Association, married 16-year-old Katie Wynn, and eventually signed with Connie Mack to play Major League baseball for the Philadelphia Athletics.[8]

For the first two years of his career, Jackson had some trouble adjusting to life with the Athletics; reports conflict as to whether he just did not like the big city, or if he was bothered by hazing from teammates. Consequently, he spent a great portion of that time in the minor leagues. Between 1908 and 1909, Jackson appeared in just 10 games.[9] During the 1909 season, Jackson played 118 games for the South Atlantic League team in Savannah, Georgia. He batted .358 for the year.

Major League career

The Athletics finally gave up on Jackson in 1910 and traded him to the Cleveland Naps. He spent most of 1911 with the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern Association, where he won the batting title and led the team to the pennant. Late in the season, he was called up to play on the big league team. He appeared in 20 games and hit .387. In 1911, Jackson's first full season, he set a number of rookie records. His .408 batting average that season is a record that still stands and was good for second overall in the league behind Ty Cobb. The following season, Jackson batted .395 and led the American League in triples. On April 20, 1912, Shoeless Joe Jackson scored the first run in Tiger Stadium. [10] The next year, he led the league with 197 hits and a .551 slugging percentage.

In August 1915, Jackson was traded to the Chicago White Sox. Two years later, Jackson and the White Sox won the American League pennant and also the World Series. During the series, Jackson hit .307 as the White Sox defeated the New York Giants.

Jackson sat most of 1918 due to World War I. In 1919, he came back strong to post a .351 average during the regular season and .375 with perfect fielding in the World Series. However, the heavily-favored White Sox lost the series to the Cincinnati Reds. The next season, Jackson batted .385 and was leading the American league in triples when he was suspended, along with seven other members of the White Sox, after allegations surfaced that the team had thrown the previous World Series.

Black Sox scandal

After the White Sox unexpectedly lost the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds, eight players, including Jackson, were accused of throwing the Series to the Reds. In September 1920, a grand jury was convened to investigate.

During the series, Jackson had 12 hits and a .375 batting average — in both cases leading both teams. The 12 hits were a World Series record. He committed no errors and even threw out a runner at the plate.[11]

It is often said that the Cincinnati Reds hit an unusually high number of triples to left field where Jackson played during the series.[12] This is not supported by the contempory newspaper accounts. According to first hand accounts, none of the triples were hit to left field.[13] In fact, more triples were muffed by Shano Collins than were hit to Jackson. (Collins was ironically listed as the wronged party in the indictments of the conspirators. The indictments claimed he was defrauded of $1,784 ($42,427 in current dollar terms) by the actions of those charged.)

In testimony before the grand jury on September 28, 1920, Jackson admitted under oath that he agreed to participate in the fix. Contemporary news accounts contend that Jackson told the grand jury:

"When a Cincinnati player would bat a ball out in my territory I'd muff it if I could — that is, fail to catch it. But if it would look too much like crooked work to do that I'd be slow and make a throw to the infield that would be short. My work netted the Cincinnati team several runs that they never would have had if we had been been playing on the square."[14]

No such direct quote or testimony to this effect appears in the actual stenographic record of Jackson's grand jury appearance.[15]

Jackson did, however, admit to receiving a cash payment of $5,000 ($118,909 in current dollar terms) and that he had been originally promised a $20,000 ($475,636 in current dollar terms) bribe. Legend has it that as Jackson was leaving the courthouse during the trial, a young boy begged of him, "Say it ain't so, Joe," and that Joe did not respond. In an interview in Sport Magazine nearly three decades later, Jackson contended that this story was a myth.[16] A contemporary press account does refer to an exchange of Jackson with young fans outside of the Chicago grand jury hearing on September 28:

When Jackson left criminal court building in custody of a sheriff after telling his story to the grand jury, he found several hundred youngsters, aged from 6 to 16, awaiting for a glimpse of their idol. One urchin stepped up to the outfielder, and, grabbing his coat sleeve, said:

"It ain't true, is it, Joe?"

"Yes, kid, I'm afraid it is," Jackson replied. The boys opened a path for the ball player and stood in silence until he passed out of sight.

"Well, I'd never have thought it," sighed the lad.[17]

Regardless of whether Jackson's exchange with the shocked young fan was a true historical event or a fabrication by a sensationalist journalist, the "Say It Ain't So" story remains an oft-repeated and well-known part of baseball lore.

In 1921, a Chicago jury acquitted him and his seven White Sox teammates of wrongdoing. Nevertheless, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the newly appointed Commissioner of Baseball, banned all eight accused players, claiming baseball's need to clean up its image took precedence over legal judgments. As a result, Jackson never played major league baseball after the 1920 season.

Aftermath

During the remaining 20 years of his baseball career, Jackson played and managed with a number of minor league teams, most located in Georgia and South Carolina.[7] In 1922, Jackson returned to Savannah and opened a dry cleaning business.

In 1933, the Jacksons moved back to Greenville, South Carolina. After first opening a barbecue restaurant, Jackson and his wife opened "Joe Jackson's Liquor Store," which they operated until his death. One of the better known stories of Jackson's post-major league life took place at his liquor store. Ty Cobb and sportswriter Grantland Rice entered the store, with Jackson showing no sign of recognition towards Cobb. After making his purchase, the incredulous Cobb finally asked Jackson, "Don't you know me, Joe?" Jackson replied, "Sure, I know you, Ty, but I wasn't sure you wanted to know me. A lot of them don't."[18] This anecdote, like many others in Cobb's autobiography, is probably apocryphal.

As he aged, Jackson began to suffer from heart trouble. In 1951, at the age of 63, Jackson died of a heart attack.[7] He is buried at nearby Woodlawn Memorial Park. He had no children.

Dispute over Jackson's innocence

To this day, his name remains on the Major League Baseball ineligible list. Jackson cannot be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame unless his name is removed from that list. However, he spent most of the last 30 years of his life proclaiming his innocence. In November 1999, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a motion to honor his sporting achievements, supporting a move to have the ban posthumously rescinded, so that he could be admitted to the Hall of Fame.[19] The motion was symbolic, as the U.S. Government has no jurisdiction in the matter. At the time, MLB commissioner Bud Selig claimed that Jackson's case was under review, but to date, no action has been taken that would allow Jackson's reinstatement.

In recent years, evidence has come to light that casts doubt on Jackson's role in the fix. For instance, Jackson initially refused to take a payment of $5,000, only to have Lefty Williams toss it on the floor of his hotel room. Jackson then tried to tell White Sox owner Charles Comiskey about the fix, but Comiskey refused to meet with him. Also, before Jackson's grand jury testimony, team attorney Alfred Austrian coached Jackson's testimony in a manner that would be considered highly unethical even by the standards of the time, and would probably be considered criminal by today's standards. For instance, Austrian got Jackson to admit a role in the fix by pouring a large amount of whiskey down Jackson's throat. He also got the nearly illiterate Jackson to sign a waiver of immunity. Years later, the other seven players implicated in the scandal confirmed that Jackson was never at any of the meetings. Williams, for example, said that they only mentioned Jackson's name to give their plot more credibility.[11]

An article in the September issue of Chicago Lawyer magazine[20] argues that Eliot Asinof's 1963 book, Eight Men Out, which seemed to confirm Jackson's guilt, was based on inaccurate information, as well as the insertion of fictional characters into the book.

The League Park Society, Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum, Shoeless Joe Jackson Virtual Hall of Fame, and the Cleveland Blues have teamed up to start a campaign to push Major League Baseball to lift the ban and allow Jackson into the Hall of Fame.

Career statistics

See: Baseball statistics for an explanation of these statistics.

| G | AB | H | 2B | 3B | HR | R | RBI | BB | SO | AVG | OBP | SLG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,332 | 4,981 | 1,772 | 307 | 168 | 54 | 873 | 785 | 519 | 158 | .356 | .423 | .517 |

Films and plays

Shoeless Joe has been depicted in a few films in the late 20th century. Eight Men Out, a film directed by John Sayles, based on the Eliot Asinof book of the same name, details the Black Sox scandal in general and has D. B. Sweeney portraying Jackson.

The Phil Alden Robinson film Field of Dreams, based on Shoeless Joe by W. P. Kinsella, stars Ray Liotta as Jackson. Kevin Costner plays an Iowa farmer who hears a mysterious voice instructing him to build a baseball field on his farm so Shoeless Joe can play baseball again. (Although Liotta portrays Jackson as batting right-handed, whereas Jackson actually batted left).

Jackson's nickname was worked into the musical play Damn Yankees. The lead character, baseball phenomenon Joe Hardy, alleged to be from a small town in Missouri, is dubbed by the media as "Shoeless Joe from Hannibal, MO." The play also contains a plot element alleging that Joe had thrown baseball games in his earlier days.

Jackson was also an inspiration, in part, for the character Roy Hobbs in The Natural. Hobbs has a special name for his bat (as Jackson did), and is offered a bribe to throw a game. In the book (but not the film), a youngster pleads with Hobbs, "Say it ain't so, Roy!"

Legacy

Even though Jackson was banned from Major League baseball, people after his death would build parks and statues for him. One of the landmarks built for him was a Memorial Ballpark which can be found in Greenville, South Carolina. The baseball field that was built in his name is called the West End Field.

A local Greenville radio station, WMRB 1490 AM (now WPCI), carried the Chicago White Sox radio broadcasts during the 50's and 60's. Some local listeners falsely conjectured the Chicago White Sox broadcasts were the result of Shoeless Joe Jackson’s affiliation with the White Sox and his playing time with Brandon Mills of the Textile Baseball League. Although incorrect, this speculation may have inadvertently fueled Shoeless Joe's popularity.[21]

Joe Jackson also had a memorial sculpture made after him, which also stands in Greenville, South Carolina. The sculptor of the piece was a man named Doug Young. In 2006, Joe Jackson's original home was moved to a location adjacent to Fluor Field at the West End in downtown Greenville, South Carolina. The home was restored and opened in 2008 as the Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum and Baseball Library. The address is 356 Field St., in honor of his lifetime batting average.

Popular culture

- In a Futurama episode, Bender mentions a robot blurnsball player named Wireless Joe Jackson.

- Shoeless Joe is featured in "Kenesaw Mountain Landis", a song by folk/rock singer Jonathan Coulton which is very loosely based on the story of the Black Sox Scandal.

- A song "Shoeless Joe", performed by Bill Scholer, is featured on the sixth edition of Diamond Cuts, Bottom of the Sixth.

- In the Japanese drama Love Shuffle, The story behind the quote "Say it ain't so, Joe" is explained by one of the main characters within the first few minutes of the series. "Say it ain't so, Joe" then becomes a line that is repeated by all of the main characters whenever an incredulous situation arises.

- Sarah Palin said to Joe Biden during a 2009 U.S. Presidential debate, "Say it ain't so, Joe."

See also

- Chicago White Sox all-time roster

- List of Major League Baseball doubles champions

- List of Major League Baseball triples champions

- List of Major League Baseball triples records

- List of Major League Baseball leaders in career stolen bases

References

- ^ Although he was in the majors as early as 1908, Major League rules at the time stipulated that a player was considered a rookie until he has had more than 130 at-bats in a season.[1]

- ^ "The Baseball Page". thebaseballpage.com/players/jacksjo01.php. Retrieved December 11, 2006.

- ^ Listed at .340, his batting average while with the franchise.

- ^ Honig, Donald. The Man in the Dugout.

- ^ "Black Betsy Sale". shoelessjoejackson.com. Retrieved November 26, 2006.

- ^ "Signature Sale". jondube.com. Retrieved January 1, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Joe Jackson Timeline". blackbetsy.com. Retrieved November 26, 2006.

- ^ a b "Chicago Historical Society". chicagohs.com. Retrieved December 11, 2006.

- ^ "JoeJackson.com Biography". shoelessjoejackson.com. Retrieved December 11, 2006.

- ^ The Final Season, p.5, Tom Stanton, Thomas Dunne Books, An imprint of St. Martin’s Press, New York, NY, 2001, ISBN 0-312-29156-6

- ^ a b Purdy, Dennis (2006). The Team-by-Team Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball. New York City: Workman. ISBN 0761139435.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Neyer, Rob. Say it ain't so ... for Joe and the Hall. ESPN Classic.com. 30 August 2007.

- ^ http://www.blackbetsy.com/1919triples.htm

- ^ "Attell Says He Will Have Plenty to Say," Minnesota Daily Star, September 29, 1920, pg. 5

- ^ The testimony is available as a downloadable pdf at http://www.blackbetsy.com/jjtestimony1920.pdf

- ^ Joe Jackson: This is the Truth

- ^ "'It Ain't Ture, Is It, Joe?' Youngster Asks," Minnesota Daily Star, September 29, 1920, pg. 5

- ^ "Ty Cobb & Joe Jackson story" (PDF). www.pde.state.pa.us. Retrieved November 23, 2006.

- ^ "U.S. House Backs Shoeless Joe". CBS.com. Retrieved May 29, 2008.

- ^ http://www.chicagolawyermagazine.com/2009/09/01/black-sox-it-aint-so-kid-it-just-aint-so/

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WPCI

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WPCI

Bibliography

- "Shoeless: The Life And Times of Joe Jackson", by David L. Fleitz (2001, McFarland & Company Publishers)

- Shoeless Joe, a novel by W. P. Kinsella

- Eight Men Out, by Eliot Asinof

- Say It Ain't So, Joe!: The True Story of Shoeless Joe Jackson, by Donald Gropman

- Joe Jackson: A Biography, by Kelly Boyer Sagert

- A Man Called Shoeless, by Howard Burman

- "Burying the Black Sox" (Potomac, Spring 2006) by Gene Carney

- "Shoeless Joe & Me" (HarperCollins, 2002) by Dan Gutman

External links

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs

- Shoeless Joe Jackson at Find a Grave

- Joe Jackson Plaza in Greenville, SC

- Petition asking Bud Selig to reinstate Shoeless Joe

- ShoelessJoeJackson.com - Jackson's Official Web Site

- The letter written by Commissioner Landis banning Jackson from baseball

- Shoeless Joe Jackson Ballpark site

- 1888 births

- 1951 deaths

- Chicago White Sox players

- Cleveland Indians players

- Cleveland Naps players

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- Greenville Spinners players

- Major League Baseball controversies

- Major League Baseball outfielders

- Major League Baseball players from South Carolina

- New Orleans Pelicans players

- People from Greenville, South Carolina

- People from New Orleans, Louisiana

- People from Pickens County, South Carolina

- Philadelphia Athletics players

- Savannah Indians players