Gerrit Smith: Difference between revisions

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

On June 2, 1848 in [[Rochester, New York]], Smith was nominated as the [[Liberty Party (1840s)|Liberty Party]]'s presidential candidate.<ref name=Wellman176>Wellman, 2004, p. 176.</ref> At the National Liberty Convention, held June 14–15 in [[Buffalo, New York]], Smith gave a major address,<ref>Claflin, Alta Blanche. [http://books.google.com/books?id=c10PAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA50 ''Political parties in the United States 1800-1914''], New York Public Library, 1915, p. 50</ref> including in his speech a demand for "universal suffrage in its broadest sense, females as well as males being entitled to vote."<ref name=Wellman176/> The delegates approved a passage in their address to the people of the united states addressing votes for women: "Neither here, nor in any other part of the world, is the right of suffrage allowed to extend beyond one of the sexes. This universal exclusion of woman... argues, conclusively, that, not as yet, is there one nation so far emerged from barbarism, and so far practically Christian, as to permit woman to rise up to the one level of the human family."<ref name=Wellman176/> |

On June 2, 1848 in [[Rochester, New York]], Smith was nominated as the [[Liberty Party (1840s)|Liberty Party]]'s presidential candidate.<ref name=Wellman176>Wellman, 2004, p. 176.</ref> At the National Liberty Convention, held June 14–15 in [[Buffalo, New York]], Smith gave a major address,<ref>Claflin, Alta Blanche. [http://books.google.com/books?id=c10PAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA50 ''Political parties in the United States 1800-1914''], New York Public Library, 1915, p. 50</ref> including in his speech a demand for "universal suffrage in its broadest sense, females as well as males being entitled to vote."<ref name=Wellman176/> The delegates approved a passage in their address to the people of the united states addressing votes for women: "Neither here, nor in any other part of the world, is the right of suffrage allowed to extend beyond one of the sexes. This universal exclusion of woman... argues, conclusively, that, not as yet, is there one nation so far emerged from barbarism, and so far practically Christian, as to permit woman to rise up to the one level of the human family."<ref name=Wellman176/> |

||

Smith, along with his friend and ally [[Lysander Spooner]], was one of the leading advocates of the [[United States Constitution]] as an antislavery document, as opposed to [[William Lloyd Garrison]] who believed it was pro-slavery. In 1852, Smith was elected to the [[United States House of Representatives]] as a [[Free Soil Party|Free-Soiler]], and in his address he declared that all men have an equal right to the soil; that wars are brutal and unnecessary; that slavery could be sanctioned by no constitution, state or federal; that free trade is essential to human brotherhood; that women should have full political rights; that the Federal government and the states should prohibit the liquor traffic within their respective jurisdictions; and that government officers, so far as practicable, should be elected by direct vote of the people. At the end of the first session he resigned his seat, largely out of frustration concerning the seemingly imminent passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act.{{Fact|date=August 2008}} Smith, disillusioned by the apparent failure of electoral change, brought his political life quickly to a close. He emerged later, however, even more strongly radical than before.{{Fact|date=August 2008}} |

Smith, along with his friend and ally [[Lysander Spooner]], was one of the leading advocates of the [[United States Constitution]] as an antislavery document, as opposed to abolitionist [[William Lloyd Garrison]] who believed it was to be condemned as a pro-slavery document. In 1852, Smith was elected to the [[United States House of Representatives]] as a [[Free Soil Party|Free-Soiler]], and in his address he declared that all men have an equal right to the soil; that wars are brutal and unnecessary; that slavery could be sanctioned by no constitution, state or federal; that free trade is essential to human brotherhood; that women should have full political rights; that the Federal government and the states should prohibit the liquor traffic within their respective jurisdictions; and that government officers, so far as practicable, should be elected by direct vote of the people. At the end of the first session he resigned his seat, largely out of frustration concerning the seemingly imminent passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act.{{Fact|date=August 2008}} Smith, disillusioned by the apparent failure of electoral change, brought his political life quickly to a close. He emerged later, however, even more strongly radical than before.{{Fact|date=August 2008}} |

||

==Social activism== |

==Social activism== |

||

Revision as of 21:38, 28 August 2010

Gerrit Smith | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 6, 1797 |

| Died | December 28, 1874 (aged 77) |

| Occupation(s) | social reformer, abolitionist, politician, philanthropist |

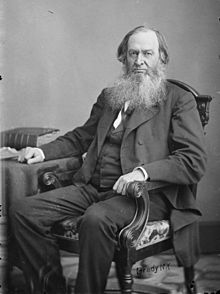

Gerrit Smith (March 6, 1797 – December 28, 1874) was a leading United States social reformer, abolitionist, politician, and philanthropist. He was an unsuccessful candidate for President of the United States in 1848, 1852, and 1856.

Smith, a significant financial contributor to the Liberty Party and the Republican Party throughout his life, spent much time and money working towards social progress in the nineteenth century United States. Besides making substantial donations of both land and money to the African American community in North Elba, New York, he was involved in the Temperance Movement and, later in life, the colonization movement.[1] A staunch abolitionist, he was a member of the Secret Six that financially supported John Brown's raid at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.[2]

Early life

Smith was born in Utica, Oneida County, New York, to Peter Gerrit Smith (1768–1837) and Elizabeth Livingston (1773–1818), daughter of Col. James Livingston (1747–1832) of Schuylerville, Saratoga County, New York, and Elizabeth Simpson (1750–1800). His grandfather, James Livingston, fought at the battles of Quebec and Saratoga during the American Revolution and is credited with thwarting Benedict Arnold's attempted treason by firing on the Vulture, the boat intended to carry Arnold and his British contact, Maj. John André, to safety. [3] Smith's maternal aunt, Margaret Livingston, married Daniel Cady of Johnstown, New York. Their daughter, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a founder and leader of the women's suffrage movement, was Smith's first cousin. In fact, Elizabeth Cady met her future husband, Henry Stanton, himself an active abolitionist, at the Smith family home in Peterboro, New York.[4] Established in 1795, the town had been founded by and named for Gerrit Smith's father, Peter Smith, who built the family homestead there in 1804.[5]

After graduating from Hamilton College in 1818, Smith took on the management of the vast estate of his father, a long-standing partner of John Jacob Astor, and greatly increased the family fortune. In 1822, he married Ann Carroll Fitzhugh (1805-1879, sister of Henry Fitzhugh), and they had two children: Elizabeth Smith (1822-1911) and Greene Smith (ca. 1841-1880).[6]

About 1828 Smith became an active temperance campaigner, and in his hometown of Peterboro, he built one of the first temperance hotels in the country. He became an abolitionist in 1835, after attending an anti-slavery meeting in Utica, New York, which had been broken up by a mob.

Political career

In 1840 Smith played a leading part in the organization of the Liberty Party. In the same year, their presidential candidate James G. Birney married Elizabeth Potts Fitzhugh, Smith's sister-in-law. In 1848, Smith was nominated for the Presidency by the remnant of this organization that had not been absorbed by the Free Soil Party. An "Industrial Congress" at Philadelphia also nominated him for the presidency in 1848, and the "Land Reformers" in 1856. In 1840 and again in 1858, he ran for Governor of New York on an anti-slavery platform.

On June 2, 1848 in Rochester, New York, Smith was nominated as the Liberty Party's presidential candidate.[7] At the National Liberty Convention, held June 14–15 in Buffalo, New York, Smith gave a major address,[8] including in his speech a demand for "universal suffrage in its broadest sense, females as well as males being entitled to vote."[7] The delegates approved a passage in their address to the people of the united states addressing votes for women: "Neither here, nor in any other part of the world, is the right of suffrage allowed to extend beyond one of the sexes. This universal exclusion of woman... argues, conclusively, that, not as yet, is there one nation so far emerged from barbarism, and so far practically Christian, as to permit woman to rise up to the one level of the human family."[7]

Smith, along with his friend and ally Lysander Spooner, was one of the leading advocates of the United States Constitution as an antislavery document, as opposed to abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison who believed it was to be condemned as a pro-slavery document. In 1852, Smith was elected to the United States House of Representatives as a Free-Soiler, and in his address he declared that all men have an equal right to the soil; that wars are brutal and unnecessary; that slavery could be sanctioned by no constitution, state or federal; that free trade is essential to human brotherhood; that women should have full political rights; that the Federal government and the states should prohibit the liquor traffic within their respective jurisdictions; and that government officers, so far as practicable, should be elected by direct vote of the people. At the end of the first session he resigned his seat, largely out of frustration concerning the seemingly imminent passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act.[citation needed] Smith, disillusioned by the apparent failure of electoral change, brought his political life quickly to a close. He emerged later, however, even more strongly radical than before.[citation needed]

Social activism

After becoming an opponent of land monopoly, he gave numerous farms of 50 acres (200,000 m²) each to indigent families. In 1846, hoping to help black families become self-sufficient and to provide them with the property ownership needed to vote in New York, Smith attempted to colonize approximately 120,000 acres (490 km2) of land in North Elba, New York, near Lake Placid in Essex County with free blacks. The difficulty of farming in the Adirondack region, coupled with the settlers lack of experience in housebuilding and the bigotry of white neighbors, caused the experiment to fail.[9]

Peterboro became a station on the Underground Railroad, and, after 1850, Smith furnished money for the legal expenses of persons charged with infractions of the Fugitive Slave Law.[10] Smith became a leading figure in the Kansas Aid Movement, a campaign to raise money and show solidarity with anti-slavery immigrants to that territory.[citation needed] It was during this movement that he first met and financially supported John Brown.[citation needed] He later became more closely acquainted with John Brown, to whom he sold a farm in North Elba, and from time to time supplied him with funds. In 1859, Smith joined the Secret Six, a group of wealthy northern abolitionists, who supported Brown in his efforts to capture the armory at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia (then Virginia) and arm the slaves. After the failed raid on Harpers Ferry, Senator Jefferson Davis unsuccessfully attempted to have Smith accused, tried, and hanged along with Brown.[10] Upset by the raid, its outcome, and aftermath, Smith suffered a mental breakdown, and for several weeks was confined to the state asylum in Utica.[11]

When the Chicago Tribune later claimed Smith had full knowledge of Brown's plan at Harper's Ferry, Smith sued the paper for libel, claiming that he lacked any such knowledge and thought only that Brown wanted guns so that slaves who ran away to join him might defend themselves against attackers. Smith's claim was countered by the Tribune, which produced an affidavit, signed by Brown's son, swearing that Smith had full knowledge of all the particulars of the plan, including the plan to instigate a slave uprising. In writing later of these events, Smith said, "That affair excited and shocked me, and a few weeks after I was taken to a lunatic asylum. From that day to this I have had but a hazy view of dear John Brown's great work. Indeed, some of my impressions of it have, as others have told me, been quite erroneous and even wild."[11]

Smith was a major benefactor of New-York Central College, McGrawville, a co-educational and racially integrated college in Cortland County.[citation needed]

Smith was in favor of the Civil War, but at its close he advocated a mild policy toward the late Confederate states, declaring that part of the guilt of slavery lay upon the North. In 1867, Smith, together with Horace Greeley and Cornelius Vanderbilt, helped to underwrite the $1,000,000 bond needed to free Jefferson Davis, who had, at that time, been imprisoned for nearly two years without being charged with any crime. [12] In doing this, Smith incurred the resentment of Northern Radical Republican leaders.

Smith's passions extended to religion as well as politics. Believing that sectarianism was sinful, he separated from the Presbyterian Church in 1843, and was one of the founders of the Church at Peterboro, a non-sectarian institution open to all Christians of whatever denomination.

His private benefactions were substantial; of his gifts he kept no record,[citation needed] but their value is said to have exceeded $8,000,000.[citation needed] Though a man of great wealth, his life was one of marked simplicity.[citation needed] He died in 1874 while visiting relatives in New York City.

The Gerrit Smith Estate, in Peterboro, New York, was declared a National Historic Landmark in 2001.[13][14]

Notes and sources

- ^ Stauffer, The Black Hearts of Men, p. 265

- ^ Renehan, pp.13-14

- ^ Griffith, p.4

- ^ Griffith, p.26

- ^ Renehan, p.16; Historic Peterboro

- ^ [1] Fitzhugh genealogy

- ^ a b c Wellman, 2004, p. 176.

- ^ Claflin, Alta Blanche. Political parties in the United States 1800-1914, New York Public Library, 1915, p. 50

- ^ Renehan, pp 17-18

- ^ a b Renehan, p.12

- ^ a b Renehan, pp.13-14

- ^ Renehan, p.11

- ^ "Gerrit Smith Estate". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2008-01-17.

- ^ LouAnn Wurst (September 21, 2001), Template:PDFlink, National Park Service

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - United States Congress. "Gerrit Smith (id: S000542)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2009-04-15

- Frothingham, O. B., Gerrit Smith: a Biography (New York, 879). ISBN 0-7812-2907-3.

- Griffith, Elizabeth, In Her Own Right: The Life of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Oxford University Press; New York. 1984. ISBN 0-195-03729-4. (pp. 3–26)

- NYHistory.com. Historic Peterboro

- Renehan, Edward J., The Secret Six: The True Tale of the Men Who Conspired with John Brown. New York. Crown Publishers, Inc.; 1995. ISBN 0-517-59028-X.

- Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls, University of Illinois Press, 2004. ISBN 0-252-02904-6