Human sternum: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

→Fractures of the sternum: sternal foramen, why wasn't this here already? |

||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

A somewhat rare congenital condition of the sternum is a sternal foramen, a single round hole in the sternum that is present from birth and usually is off-centered to the right or left, commonly forming in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th segments of the sternum body. Sternal foramens can often be mistaken for bullet holes. |

|||

==In other animals== |

==In other animals== |

||

Revision as of 03:45, 3 December 2010

| Sternum | |

|---|---|

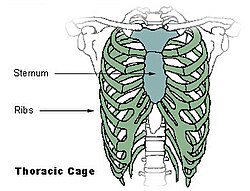

Thoracic cage | |

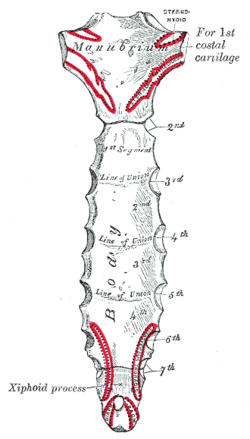

Posterior surface of sternum. | |

| Anatomical terms of bone |

The sternum (plural sterna or sternums, from Greek στέρνον,sternon, "chest" or breastbone) is a long flat bony plate shaped like a capital "T" located anteriorly to the heart in the center of the thorax (chest). It connects the rib bones via cartilage, forming the anterior section of the rib cage with them, and thus helps to protect the lungs, heart and major blood vessels from physical trauma. Although it is fused, the sternum can be sub-divided into three regions: the manubrium, the body, and the xiphoid process. [1]

The sternum is sometimes cut open (a median sternotomy) to gain access to the thoracic contents when performing cardiothoracic surgery.

Overview

The sternum is an elongated, flattened bone, forming the middle portion of the anterior wall of the thorax. The superior end supports the clavicles (Collar bones), and its margins articulate with the cartilages of the first seven pairs of ribs. Its top is also connected to the Sternocleidomastoid muscle. It consists of three main parts, listed superior to inferior:

- Manubrium

- Body of sternum (gladiolus)

- Xiphoid process

In its natural position, the inclination of the bone is oblique from above, downward and forward. It is slightly convex in front and concave behind; broad above, shaped like a "T", becoming narrowed at the point where the manubrium joins the body, after which it again widens a little to below the middle of the body, and then narrows to its lower extremity. Its average length in the adult is about 17 cm, and is rather longer in the male than in the female.

In early life its body is divided in four segments, called sternebrœ (singular: sternebra).

Structure

The manubrium (ma-NOO-bree-um) is the broad superior portion of the sternum. The suprasternal (jugular) notch is medially located at the superior end of the manubrium. You can feel this notch between your two clavicles (collarbones). Located superiorly and laterally are the right and left clavicular notches.[1]

The body, or gladiolus, is the longest part of the sternum. The sternal angle is located at the point where the body joins the manubrium. The sternal angle can be felt at the point where the sternum projects farthest forward. However, in some people the sternal angle is concave or rounded. During physical examinations, the sternal angle is a useful landmark when counting ribs because the second rib attaches here.[1]

Located at the inferior end of the sternum, is the pointed xiphoid (ZIF-oyd) process. Improperly performed chest compressions during cardiopulmonary resuscitation can cause the xiphoid process to snap off, driving it into the liver which can cause a fatal hemorrhage.[1]

The sternum is composed of highly vascular tissue, covered by a thin layer of compact bone which is thickest in the manubrium between the articular facets for the clavicles.

Articulations

The superior seven costal cartilages articulate with the sternum forming the costal margin anteriorly. The right and left clavicular notches articulate with the right and left clavicles, respectively. The costal cartilage of the second rib articulates with the sternum at the sternal angle making it easy to locate.[2]

The transverse thoracis muscle is innervated by the intercostal nerve and superiorly attaches at the posterior surface of the lower sternum. Its inferior attachment is the internal surface of costal cartilages two through six and works to depress the ribs. [3]

Fractures of the sternum

Fractures of the sternum are rather uncommon. They may result from trauma, such as when a driver's chest is forced into the steering column of a car in a car accident. A fracture of the sternum is usually a comminuted fracture. The most common site of sternal fractures is at the sternal angle. Some studies reveal that repeated punches or continual beatings, sometimes called "sternum punches", to the sternum area have also caused fractured sternums. Those are known to have occurred in contact sports such as rugby and football. Sternum fractures are frequently associated with underlying injuries such as pulmonary contusions, or bruised lung tissue.[4] A somewhat rare congenital condition of the sternum is a sternal foramen, a single round hole in the sternum that is present from birth and usually is off-centered to the right or left, commonly forming in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th segments of the sternum body. Sternal foramens can often be mistaken for bullet holes.

In other animals

The sternum probably first evolved in early tetrapods as an extension of the pectoral girdle; it is not found in fish. In amphibians and reptiles it is typically a shield-shaped structure, often composed entirely of cartilage. It is absent in both turtles and snakes. In birds it is a relatively large bone and (except in ratites) bears an enormous projecting keel to which the flight muscles are attached.[5]

Only in mammals does the sternum take on the elongated, segmented form seen in humans. In some mammals, such as opossums, the individual segments, or sternebrae, never fuse and remain separated by cartilagenous plates throughout life.[5]

References

- ^ a b c d Saladin, Kenneth S. (2010). Anatomy and Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function, Fifth Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-07-352569-3.

- ^ Agur, Anne M.R.; Dalley, Arthur F. II (2009). Grant's Atlas of Anatomy, Twelfth Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7817-7055-2.

- ^ Agur, Anne M.R.; Dalley, Arthur F. II (2009). Grant's Atlas of Anatomy, Twelfth Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7817-7055-2.

- ^

Sattler S, Maier RV (2002). "Pulmonary contusion". In Karmy-Jones R, Nathens A, Stern EJ (ed.). Thoracic Trauma and Critical Care. Berlin: Springer. pp. 235–243. ISBN 1-4020-7215-5. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. p. 188. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.