In Search of Lost Time: Difference between revisions

→Themes: tidy up sentence to make more sense |

→Adaptations: - added one 's' to 'hausmann' |

||

| Line 168: | Line 168: | ||

;Screen |

;Screen |

||

* ''Swann in Love'' (''Un Amour de Swann''), a 1984 film by [[Volker Schlöndorff]] starring [[Jeremy Irons]] and [[Ornella Muti]]. |

* ''Swann in Love'' (''Un Amour de Swann''), a 1984 film by [[Volker Schlöndorff]] starring [[Jeremy Irons]] and [[Ornella Muti]]. |

||

*"102 Boulevard |

*"102 Boulevard Haussmann", a 1990 made-for-TV movie that aired as part of the BBC's "Screen Two" series, starring [[Allen Bates]]. [http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0101246/] |

||

* ''[[Time Regained (film)|Time Regained]]'' (''Le Temps retrouvé''), a 1999 film by [[Raul Ruiz]] starring [[Catherine Deneuve]], [[Emmanuelle Béart]], and [[John Malkovich]]. |

* ''[[Time Regained (film)|Time Regained]]'' (''Le Temps retrouvé''), a 1999 film by [[Raul Ruiz]] starring [[Catherine Deneuve]], [[Emmanuelle Béart]], and [[John Malkovich]]. |

||

* ''La Captive'', a 2000 film by [[Chantal Akerman]]. |

* ''La Captive'', a 2000 film by [[Chantal Akerman]]. |

||

Revision as of 23:39, 24 February 2011

A first galley proof of À la recherche du temps perdu: Du côté de chez Swann with Proust's handwritten corrections. | |

| Author | Marcel Proust |

|---|---|

| Original title | À la recherche du temps perdu |

| Language | French |

| Subject | Memory |

| Genre | Modernist |

| Publisher | Grasset and Gallimard |

Publication date | 1913–1927 |

| Publication place | France |

Published in English | 1922–1931 |

| ISBN | NA Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

In Search of Lost Time or Remembrance of Things Past (French: À la recherche du temps perdu) is a novel in seven volumes by Marcel Proust. His most prominent work, it is popularly known for its length and the notion of involuntary memory, the most famous example being the "episode of the madeleine". The novel is widely referred to in English as Remembrance of Things Past but the title In Search of Lost Time, a literal rendering of the French, has gained in usage since D.J. Enright's adopted it in his 1992 revision of the earlier translation by C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin. The complete story contains nearly 1.5 million words and is one of the longest novels in world literature.

The novel as we know it began to take shape in 1909 and work continued for the remainder of Proust's life, broken off only by his final illness and death in the autumn of 1922. The structure was established early on and the novel is complete as a work of art and a literary cosmos but Proust kept adding new material through his final years while editing one time after another for print; the final three volumes contain oversights and fragmentary or unpolished passages which existed in draft at the death of the author; the publication of these parts was overseen by his brother Robert.

The work was published in France between 1913 and 1927; Proust paid for the publication of the first volume (by the Grasset publishing house) after it had been turned down by leading editors who had been offered the manuscript in longhand. Many of its ideas, motifs and scenes appear in adumbrated form in Proust's unfinished novel, Jean Santeuil (1896–99), though the perspective and treatment there are different and in his unfinished hybrid of philosophical essay and story, Contre Sainte-Beuve (1908–09). The novel has had great influence on twentieth-century literature, whether because writers have sought to emulate it or attempted to parody and discredit some of its traits. Proust explores the themes of time, space and memory but the novel is above all a condensation of innumerable literary, structural, stylistic and thematic possibilities.

Initial publication

Although different editions divide the work into a varying number of tomes, A la recherche du temps perdu or In Search of Lost Time is a novel consisting of seven volumes.

| Vol. | French titles | Published | English titles |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Du côté de chez Swann | 1913 | Swann's Way The Way by Swann's |

| 2 | À l'ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs | 1919 | Within a Budding Grove In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower |

| 3 | Le Côté de Guermantes (published in two volumes) |

1920/21 | The Guermantes Way |

| 4 | Sodome et Gomorrhe (published in two volumes) |

1921/22 | Cities of the Plain Sodom and Gomorrah |

| 5 | La Prisonnière | 1923 | The Captive The Prisoner |

| 6 | La Fugitive Albertine disparue |

1925 | The Fugitive The Sweet Cheat Gone Albertine Gone |

| 7 | Le Temps retrouvé | 1927 | The Past Recaptured Time Regained Finding Time Again |

Volume 1: Du côté de chez Swann (1913) was rejected by a number of publishers, including Fasquelle, Ollendorf, and the Nouvelle Revue Française (NRF). André Gide famously was given the manuscript to read to advise NRF on publication, and leafing through the seemingly endless collection of memories and philosophizing or melancholic episodes, came across a few minor syntactic bloopers, which made him decide to turn the work down in his audit. Proust eventually arranged with the publisher Grasset to pay for the costs of publication himself. When published it was advertised as the first of a three-volume novel (Bouillaguet and Rogers, 316-7).

Du côté de chez Swann is divided into four parts: "Combray I" (sometimes referred to in English as the "Overture"), "Combray II," "Un Amour de Swann," and "Noms de pays: le nom." ('Names of places: the name'). A third-person novella within Du côté de chez Swann, "Un Amour de Swann" is sometimes published as a volume by itself. As it forms the self-contained story of Charles Swann's love affair with Odette de Crécy and is relatively short, it is generally considered a good introduction to the work and is often a set text in French schools. "Combray I" is also similarly excerpted; it ends with the famous "Madeleine cookie" episode, introducing the theme of involuntary memory.

In early 1914, André Gide, who had been involved in NRF's rejection of the book, wrote to Proust to apologize and to offer congratulations on the novel. "For several days I have been unable to put your book down.... The rejection of this book will remain the most serious mistake ever made by the NRF and, since I bear the shame of being very much responsible for it, one of the most stinging and remorseful regrets of my life" (Tadié, 611). Gallimard (the publishing arm of NRF) offered to publish the remaining volumes, but Proust chose to stay with Grasset.

Volume 2: À l'ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs (1919), scheduled to be published in 1914, was delayed by the onset of World War I. At the same time, Grasset's firm was closed down when the publisher went into military service. This freed Proust to move to Gallimard, where all the subsequent volumes were published. Meanwhile, the novel kept growing in length and in conception.

À l'ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs was awarded the Prix Goncourt in 1919.

Volume 3: Le Côté de Guermantes originally appeared as Le Côté de Guermantes I (1920) and Le Côté de Guermantes II (1921).

Volume 4: The first forty pages of Sodome et Gomorrhe initially appeared at the end of Le Côté de Guermantes II (Bouillaguet and Rogers, 942), the remainder appearing as Sodome et Gomorrhe I (1921) and Sodome et Gomorrhe II (1922). It was the last volume over which Proust supervised publication before his death in November 1922. The publication of the remaining volumes was carried out by his brother, Robert Proust, and Jacques Rivière.

Volume 5: La Prisonnière (1923), first volume of the section of the novel known as "le Roman d'Albertine" ("the Albertine novel"). The name "Albertine" first appears in Proust's notebooks in 1913. The material in these volumes was developed during the hiatus between the publication of Volumes 1 and 2, and they are a departure from the three-volume series announced by Proust in Du côté de chez Swann.

Volume 6: La Fugitive or Albertine disparue (1925) is the most editorially vexed volume. As noted, the final three volumes of the novel were published posthumously, and without Proust's final corrections and revisions. The first edition, based on Proust's manuscript, was published as Albertine disparue to prevent it from being confused with Rabindranath Tagore's La Fugitive (1921).[1] The first authoritative edition of the novel in French (1954), also based on Proust's manuscript, used the title La Fugitive. The second, even more authoritative French edition (1987–89) uses the title Albertine disparue and is based on an unmarked typescript acquired in 1962 by the Bibliothèque Nationale. To complicate matters, after the death in 1986 of Proust's niece, Suzy Mante-Proust, her son-in-law discovered among her papers a typescript that had been corrected and annotated by Proust. The late changes Proust made include a small, crucial detail and the deletion of approximately 150 pages. This version was published as Albertine disparue in France in 1987.

Volume 7: Much of Le Temps retrouvé (1927) was written at the same time as Du côté de chez Swann, but was revised and expanded during the course of the novel's publication to account for, to a greater or lesser success, the then unforeseen material now contained in the middle volumes (Terdiman, 153n3). This volume includes a noteworthy episode describing Paris during the First World War.

Themes

A la Recherche made a decisive break with the 19th century realist and plot-driven novel, populated by people of action and people representing social and cultural groups or morals. Although parts of the novel could be read as an exploration of snobbism, deceit, jealousy and suffering and although it contains a multitude of realistic details, the focus is not on the development of a tight plot or of a coherent evolution but on a multiplicity of perspectives and on the formation of experience. The protagonists of the first volume (the narrator as a boy and Swann) are by the standards of 19th century novels, remarkably introspective and passive, nor do they trigger action from other leading characters; to many readers at the time, reared on Balzac, Hugo and Tolstoy, they would not function as centers of a plot. While there is an array of symbolism in the work, it is rarely defined through explicit "keys" leading to moral, romantic or philosophical ideas. The significance of what is happening is often placed within the memory or in the inner contemplation of what is described. This focus on the relationship between experience, memory and writing and the radical de-emphasizing of the outward plot, have become staples of the modern novel but were almost unheard of in 1913.

The role of memory is central to the novel, introduced with the famous madeleine episode in the first section of the novel and in the last volume, Time Regained, a flashback similar to that caused by the madeleine is the beginning of the resolution of the story. Throughout the work many similar instances of involuntary memory, triggered by sensory experiences such as sights, sounds and smells conjure important memories for the narrator and sometimes return attention to an earlier episode of the novel. Although Proust wrote contemporaneously with Sigmund Freud, with there being many points of similarity between their thought on the structures and mechanisms of the human mind, neither author read the other (Bragg).

The madeleine episode reads:

- No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory – this new sensation having had on me the effect which love has of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me it was me. ... Whence did it come? What did it mean? How could I seize and apprehend it? ... And suddenly the memory revealed itself. The taste was that of the little piece of madeleine which on Sunday mornings at Combray (because on those mornings I did not go out before mass), when I went to say good morning to her in her bedroom, my aunt Léonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of tea or tisane. The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it. And all from my cup of tea.

Gilles Deleuze believed that the focus of Proust was not memory and the past but the narrator's learning the use of "signs" to understand and communicate ultimate reality, thereby becoming an artist.[2] While Proust was bitterly aware of the experience of loss and exclusion - loss of loved ones, loss of affection, friendship and innocent joy, which are dramatized in the novel through recurrent jealousy, betrayal and the death of loved ones - his response to this, formulated after he had discovered Ruskin, was that the work of art can recapture the lost and thus save it from destruction, at least in our minds. Art triumphs over the destructive power of time. This element of his artistic thought is clearly inherited from romantic platonism but Proust crosses it with a new intensity in describing jealousy, desire and self-doubt. (On that matter see the last quatrain of Baudelaire's poem "Une Charogne": "Then, O my beauty! say to the worms who will Devour you with kisses, That I have kept the form and the divine essence Of my decomposed love!").

The nature of art is a motif in the novel and is often explored at great length. Proust sets forth a theory of art in which we are all capable of producing art, if by this we mean taking the experiences of life and transforming them in a way that shows understanding and maturity. Writing, painting and music are also discussed at great length. Morel the violinist is examined to give an example of a certain type of "artistic" character, along with other fictional artists like the novelist Bergotte and painter Elstir.

Homosexuality

Homosexuality is another theme, particularly in the later volumes, notably in Sodom and Gomorrah, the first part of which consists of a detailed account of a sexual encounter between two of the novel's male characters. Though the narrator is heterosexual, he invariably suspects his lovers of liaisons with other women, in a repetition of the suspicions held by Charles Swann in the first volume about his mistress and eventual wife, Odette. Several characters are forthrightly homosexual, like the Baron de Charlus, while others such as the narrator's friend Robert de Saint-Loup, are only later revealed to be far more closeted. Baron De Charlus is present in the novel for the same reason Monsieur Swann is present. Swann is a wealthy man who makes a fool of himself by socializing in public with a prostitute, and one of the many themes of the novel is the vanity and shallowness of the very wealthy people with whom Proust associated during his early adulthood. Likewise, the wealthy de Charlus makes a fool of himself by his ostentatious (for that time period) display of homosexual mannerisms.

There is much debate as to how great a bearing Proust's sexuality has on understanding these aspects of the novel. Although many of Proust's close family and friends suspected that he was homosexual, Proust never admitted this. It was only after his death that André Gide, in his publication of correspondence with Proust, made public Proust's homosexuality. The nature of Proust's intimate relations with such individuals as Alfred Agostinelli and Reynaldo Hahn are well documented, though Proust was not "out and proud," except perhaps in close knit social circles. In 1949, the critic Justin O'Brien published an article in the PMLA called "Albertine the Ambiguous: Notes on Proust's Transposition of Sexes" which proposed that some female characters are best understood as actually referring to young men. Strip off the feminine ending of the names of the Narrator's lovers—Albertine, Gilberte, Andrée—and one has their masculine counterpart. This theory has become known as the "transposition of sexes theory" in Proust criticism, which in turn has been challenged in Epistemology of the Closet (1992) by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. Feminized forms of masculine names were commonplace in French-speaking countries at the end of the 19th century. A search of the 1890 Quebec census with ancestry.com, available at most public libraries, for example, reveals over 3000 Albertines.

Critical reception

In Search of Lost Time is considered the definitive Modern novel by many scholars. It has had a profound effect on subsequent writers such as the Bloomsbury Group.[3] "Oh if I could write like that!" marveled Virginia Woolf in 1922 (2:525). Proust's fame is seen in Evelyn Waugh's A Handful of Dust (1934) in which Chapter 1 is entitled "Du Côté de Chez Beaver" and Chapter 6 "Du Côté de Chez Tod."[4] (However, Waugh did not like Proust: in letters to Nancy Mitford in 1948, he wrote, "I am reading Proust for the first time ...and am surprised to find him a mental defective" and later, "I still think [Proust] insane...the structure must be sane & that is raving."[5]) Recently, literary critic Harold Bloom wrote that In Search of Lost Time is now "widely recognized as the major novel of the twentieth century."[6] Vladimir Nabokov, in a 1965 interview, named the greatest prose works of the 20th century as, in order, "Joyce's Ulysses, Kafka's The Metamorphosis, Biely's Petersburg, and the first half of Proust's fairy tale In Search of Lost Time."[7] J. Peder Zane's book The Top Ten: Writers Pick Their Favorite Books, collates 125 "top 10 greatest books of all time" lists by prominent living writers; In Search of Lost Time places eighth.[8] In the 1960s, Swedish literary critic Bengt Holmqvist dubbed the novel "at once the last great classic of French epic prose tradition and the towering precursor of the 'nouveau roman'", indicating the sixties vogue of new, experimental French prose but also, by extension, other post-war attempts to fuse different planes of location, temporality and fragmented consciousness within the same novel.[9] Pulitzer Prize winning author Michael Chabon has called it his favorite book.[10]

Since the publication in 1992 of a revised English translation by The Modern Library, based on a new definitive French edition (1987–89), interest in Proust's novel in the English-speaking world has increased. Two substantial new biographies have appeared in English, by Edmund White and William C. Carter and at least two books about the experience of reading Proust have appeared by Alain de Botton and Phyllis Rose. The Proust Society of America founded in 1997, has three chapters: at The Mercantile Library of New York City,[11] the Mechanic's Institute Library in San Francisco,[12] and the Boston Athenæum Library.

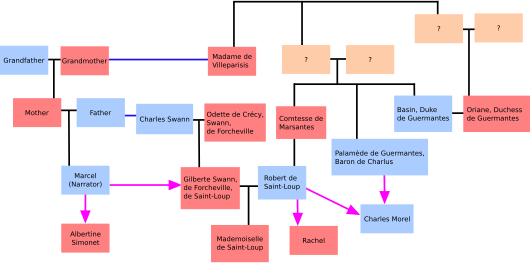

Main characters

- The Narrator's household

- The narrator: A sensitive young man who wishes to become a writer, whose identity is explicitly kept vague. In volume 5, The Prisoner, he addresses the reader thus: "Now she began to speak; her first words were 'darling' or 'my darling,' followed by my Christian name, which, if we give the narrator the same name as the author of this book, would produce 'darling Marcel' or 'my darling Marcel.'" (Proust, 64)

- Bathilde Amédée: The narrator's grandmother. Her life and death greatly influence her daughter and grandson.

- Françoise: The narrator's faithful, stubborn maid.

- The Guermantes

- Palamède de Guermantes (Baron de Charlus): An aristocratic, decadent aesthete with many antisocial habits.

- Oriane de Guermantes (Duchesse de Guermantes): The toast of Paris' high society. She lives in the fashionable Faubourg St. Germain.

- Robert de Saint-Loup: An army officer and the narrator's best friend. Despite his patrician birth (he is the nephew of M. de Guermantes) and affluent lifestyle, Saint-Loup has no great fortune of his own until he marries Gilberte.

- The Swanns

- Charles Swann: A friend of the narrator's family. His political views on the Dreyfus Affair and marriage to Odette ostracize him from much of high society.

- Odette de Crécy: A beautiful Parisian courtesan. Odette is also referred to as Mme Swann, the woman in pink/white, and in the final volume, Mme de Forcheville.

- Gilberte Swann: The daughter of Swann and Odette. She takes the name of her adopted father, M. de Forcheville, after Swann's death, and then becomes Mme de Saint-Loup following her marriage to Robert de Saint-Loup, which joins Swann's Way and the Guermantes Way.

- Artists

- Elstir: A famous painter whose renditions of sea and sky echo the novel's theme of the mutability of human life.

- Bergotte: A well-known writer whose works the narrator has admired since childhood.

- Vinteuil: An obscure musician who gains posthumous recognition for composing a beautiful, evocative sonata.

- Berma

- Others

- Charles Morel: The son of a former servant of the narrator's uncle and a gifted violinist. He profits greatly from the patronage of the Baron de Charlus and later Robert de Saint-Loup.

- Albertine Simonet: A privileged orphan of average beauty and intelligence. The narrator's romance with her is the subject of much of the novel.

- Sidonie Verdurin: A poseur who rises to the top of society through inheritance, marriage, and sheer single-mindedness. Often referred to simply as Mme. Verdurin.

Publication in English

The first six volumes were first translated into English by the Scotsman C. K. Scott Moncrieff between 1922 and his death in 1930 under the title Remembrance of Things Past, a phrase taken from Shakespeare's Sonnet 30; this was the first translation of the Recherche into another language. The final volume, Le Temps retrouvé, was initially published in English in the UK as Time Regained (1931), translated by Stephen Hudson (a pseudonym of Sydney Schiff), and in the US as The Past Recaptured (1932) in a translation by Frederick Blossom. Although cordial with Scott Moncrieff, Proust grudgingly remarked in a letter that Remembrance eliminated the correspondence between Temps perdu and Temps retrouvé (Painter, 352). Terence Kilmartin revised the Scott Moncrieff translation in 1981, using the new French edition of 1954. An additional revision by D.J. Enright - that is, a revision of a revision - was published by the Modern Library in 1992. It is based on the latest and most authoritative French text (1987–89), and rendered the title of the novel more literally as In Search of Lost Time. In 1995, Penguin undertook a fresh translation of In Search of Lost Time by editor Christopher Prendergast and seven different translators, one Australian, one American, and the others English. Based on the authoritative French text (of 1987-98), it was published in six volumes in Britain under the Allen Lane imprint in 2002. The first four (those which under American copyright law are in the public domain) have since been published in the US under the Viking imprint and in paperback under the Penguin Classics imprint. The remaining volumes are scheduled to come out in 2018.

Both the Modern Library and Penguin translations provide a detailed plot synopsis at the end of each volume. The last volume of the Modern Library edition, Time Regained, also includes Kilmartin's "A Guide to Proust," an index of the novel's characters, persons, places, and themes. The Modern Library volumes include a handful of endnotes, and alternative versions of some of the novel's famous episodes. The Penguin volumes each provide an extensive set of brief, non-scholarly endnotes that help identify cultural references perhaps unfamiliar to contemporary English readers. Reviews which discuss the merits of both translations can be found online at the Observer, the Telegraph, The New York Review of Books, The New York Times, TempsPerdu.com, and Reading Proust.

- English-language translations in print

- In Search of Lost Time (General Editor: Christopher Prendergast), translated by Lydia Davis, Mark Treharne, James Grieve, John Sturrock, Carol Clark, Peter Collier, & Ian Patterson. London: Allen Lane, 2002 (6 vols). Based on the most recent definitive French edition (1987–89), except The Fugitive, which is based on the 1954 definitive French edition. The first four volumes have been published in New York by Viking, 2003–2004, but the Copyright Term Extension Act will delay the rest of the project until 2018.

- (Volume titles: The Way by Swann's (in the U.S., Swann's Way) ISBN 0-14-243796-4; In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower ISBN 0-14-303907-5; The Guermantes Way ISBN 0-14-303922-9; Sodom and Gomorrah ISBN 0-14-303931-8; The Prisoner; and The Fugitive — Finding Time Again.)

- In Search of Lost Time, translated by C. K. Scott-Moncrieff, Terence Kilmartin and Andreas Mayor (Vol. 7). Revised by D.J. Enright. London: Chatto and Windus, New York: The Modern Library, 1992. Based on the most recent definitive French edition (1987–89). ISBN 0-8129-6964-2

- (Volume titles: Swann's Way — Within a Budding Grove — The Guermantes Way — Sodom and Gomorrah — The Captive — The Fugitive — Time Regained.)

- A Search for Lost Time: Swann's Way, translated by James Grieve. Canberra: Australian National University, 1982 ISBN 0-7081-1317-6

- Remembrance of Things Past, translated by C. K. Scott Moncrieff, Terence Kilmartin, and Andreas Mayor (Vol. 7). New York: Random House, 1981 (3 vols). ISBN 0-394-71243-9

- (Published in three volumes: Swann's Way — Within a Budding Grove; The Guermantes Way — Cities of the Plain; The Captive — The Fugitive — Time Regained.)

Adaptations

- The Proust Screenplay, a film adaptation by Harold Pinter published in 1978 (never filmed).

- Remembrance of Things Past, Part One: Combray; Part Two: Within a Budding Grove, vol.1; Part Three: Within a Budding Grove, vol.2; and Part Four: Un amour de Swann, vol.1 are graphic novel adaptations by Stéphane Heuet.

- Albertine, a novel based on a rewriting of Albertine by Jacqueline Rose. Vintage UK, 2002.

- Screen

- Swann in Love (Un Amour de Swann), a 1984 film by Volker Schlöndorff starring Jeremy Irons and Ornella Muti.

- "102 Boulevard Haussmann", a 1990 made-for-TV movie that aired as part of the BBC's "Screen Two" series, starring Allen Bates. [2]

- Time Regained (Le Temps retrouvé), a 1999 film by Raul Ruiz starring Catherine Deneuve, Emmanuelle Béart, and John Malkovich.

- La Captive, a 2000 film by Chantal Akerman.

- Quartetto Basileus (1982) uses segments from Sodom and Gomorrah and Time Regained. Le Intermittenze del cuore (2003) concerns a director working on a movie about Proust's life. Both from Italian director Fabio Carpi.[13]

- Stage

- A Waste of Time, by Philip Prowse and Robert David MacDonald. A 4 hour long adaptation with a huge cast. Dir. by Philip Prowse at the Glasgow Citizens' Theatre in 1980, revived 1981 plus European tour.

- Remembrance of Things Past, by Harold Pinter and Di Trevis, based on Pinter's The Proust Screenplay. Dir. by Trevis (who had acted in A Waste of Time - see above) at the Royal National Theatre in 2000.[14]

- Eleven Rooms of Proust, adapted and directed by Mary Zimmerman. A series of 11 vignettes from In Search of Lost Time, staged throughout an abandoned factory in Chicago.

- My Life With Albertine, a 2003 Off-Broadway musical with book by Richard Nelson, music by Ricky Ian Gordon, and lyrics by both.

- Radio

- In Search of Lost Time dramatised by Michael Butt for The Classic Serial, broadcast between February 6, 2005 and March 13, 2005. Starring James Wilby, it condensed the entire series into six episodes. Although considerably shortened, it received excellent reviews.[15]

References in popular culture

This section contains a list of miscellaneous information. (August 2008) |

- Monty Python's Flying Circus parodied the novel in a 1972 sketch called "The All-England Summarise Proust Competition" in which competitors had to summarize the book in 15 seconds. The novel had previously been mentioned by its French title in the 1970 sketch "Fish Licence" when Eric Praline (John Cleese), after proclaiming that "the late, great, Marcel Proust had an 'addock!" insists: "If you are calling the author of A la Recherche du Temps Perdu a looney...I SHALL HAVE TO ASK YOU TO STEP OUTSIDE!"

- Georges Perec wrote an article entitled 35 variations sur un thème de Marcel Proust in 1974, in which he turned the novel's famous opening line ('longtemps je me suis couché de bonne heure') into, among others, a version for athletes ('longtemps je me suis douché de bonne heure') and one for auto-erotomaniacs ('longtemps je me suis touché de bonne heure').

- The title of Andy Warhol's 1955 book, A La Recherche du Shoe Perdu, glibly references Proust's novel. The publication marked Warhol's "transition from commercial to gallery artist".[16]

- The novel is referenced by Cate Blanchett's character in Wes Anderson's "The Life Aquatic". When asked by Owen Wilson if she is reading poetry to her unborn child she replies, "No, it's a six-volume novel." The discrepancies being that "In Search of Lost Time" has seven volumes, she has seven volumes visible in frame, and she is holding "Swann's Way".

See also

Notes and references

- Notes

- ^ Calkins, Mark. Chronology of Proust's Life. TempsPerdu.com. 25 May 2005.

- ^ Ronald Bogue, Deleuze and Guattari, p. 36 See also Culler, Structuralist Poetics, p.122

- ^ Bragg, Melvyn. "In Our Time: Proust". BBC Radio 4. 17 April 2003.

- ^ Troubled Legacies, ed. Allan Hepburn, p. 256

- ^ Charlotte Mosley, ed. (1996). The Letters of Nancy Mitford and Evelyn Waugh. Hodder & Stoughton.

- ^ Farber, Jerry. "Scott Moncrieff's Way: Proust in Translation". Proust Said That. Issue No. 6. March 1997.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Grossman, Lev. "The 10 Greatest Books of All Time". Time. 15 January 2007.

- ^ Holmqvist,B. 1966, Den moderna litteraturen, Bonniers förlag, Stockholm

- ^ http://www.themorningnews.org/archives/people/michael_chabon.php

- ^ The Mercantile Library • Proust Society

- ^ Proust Society of America

- ^ Beugnet and Marion Schmid, 206

- ^ Productions: Remembrance of Things Past. NationalTheatre.org. Retrieved 25 April 2006.

- ^ Reviews of radio adaptation

- ^ Smith, John W., Pamela Allara, and Andy Warhol. Possession Obsession: Andy Warhol and Collecting. Pittsburgh, PA: Andy Warhol Museum, 2002. ISBN 0-9715688-0-4. Page 46.

- Bibliography

- Bouillaguet, Annick and Rogers, Brian G. Dictionnaire Marcel Proust. Paris: Honoré Champion, 2004. ISBN 2-7453-0956-0

- Douglas-Fairbank, Robert. "In search of Marcel Proust" in the Guardian, 17 November 2002.

- Kilmartin, Terence. "Note on the Translation." Remembrance of Things Past. Vol. 1. New York: Vintage, 1981: ix-xii. ISBN 0-394-71182-3

- Painter, George. Marcel Proust: A Biography. Vol. 2. New York: Random House, 1959. ISBN 0-394-50041-5

- Proust, Marcel. (Carol Clark, Peter Collier, trans.) The Prisoner and The Fugitive. London: Penguin Books Ltd, 2003. ISBN 0-14-118035-8

- Shattuck, Roger. Proust's Way: A Field Guide To In Search of Lost Time. New York: W W Norton, 2000. ISBN 0-393-32180-0

- Tadié, J-Y. (Euan Cameron, trans.) Marcel Proust: A Life. New York: Penguin Putnam, 2000. ISBN 0-14-100203-4

- Terdiman, Richard. Present Past: Modernity and the Memory Crisis. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1993. ISBN 0-8014-8132-5

- Woolf, Virginia. The Letters of Virginia Woolf. Eds. Nigel Nicolson and Joanne Trautmann. 7 vols. New York: Harcourt, 1976,1977.

- Beugnet, Martin and Schmid, Marion. Proust at the Movies. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004.

Further reading

- Carter, William C. Marcel Proust: A Life. New Haven: Yale UP, 2000. ISBN 0-300-08145-6

- de Botton, Alain. How Proust Can Change Your Life. New York: Pantheon 1997. ISBN 0-679-44275-8

- Deleuze, Gilles. Proust and Signs. (Translation by Richard Howard.) George Braziller, Inc. 1972.

- O'Brien, Justin. "Albertine the Ambiguous: Notes on Proust's Transposition of Sexes" PMLA 64: 933-52, 1949.

- Proust, Marcel. Albertine disparue. Paris: Grasset, 1987. ISBN 2-246-39731-6

- Rose, Phyllis. The Year of Reading Proust. New York: Scribner, 1997. ISBN 0-684-83984-9

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Epistemology of the Closet. Berkeley: U of California P, 1992. ISBN 0-520-07874-8

- White, Edmund. Marcel Proust. New York: Penguin USA, 1999. ISBN 0-670-88057-4

External links

- Alarecherchedutempsperdu.com: French text

- Proust's In Search of Lost Time

- TempsPerdu.com: a site devoted to the novel

- University of Adelaide Library: electronic versions of the original novels and the translations of C. K. Scott Moncrieff

- Project Gutenberg: Proust ebooks in French and English

- Articles with trivia sections from August 2008

- 1913 novels

- 1919 novels

- 1920 novels

- 1921 novels

- 1922 novels

- 1923 novels

- 1925 novels

- 1927 novels

- Autobiographical novels

- French novels

- Novel sequences

- Philosophical novels

- Roman à clef novels

- Self-reflexive novels

- Works by Marcel Proust

- Fiction with unreliable narrators