Burning of Washington: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

| place = [[Washington, D.C.]] |

| place = [[Washington, D.C.]] |

||

| result = British razing of [[Washington, D.C.]] |

| result = British razing of [[Washington, D.C.]] |

||

| combatant1 = {{flagicon|UK}} [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|United Kingdom |

| combatant1 = {{flagicon|UK}} [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|United Kingdom]] |

||

| combatant2 = {{flag|United States|1795}} |

| combatant2 = {{flag|United States|1795}} |

||

| commander1 = {{Flag icon|UK}} [[Robert Ross (general)|Robert Ross]]<br>{{Flag icon|UK}} [[George Cockburn]] |

| commander1 = {{Flag icon|UK}} [[Robert Ross (general)|Robert Ross]]<br>{{Flag icon|UK}} [[George Cockburn]] |

||

Revision as of 00:18, 7 June 2011

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2010) |

| Burning of Washington | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

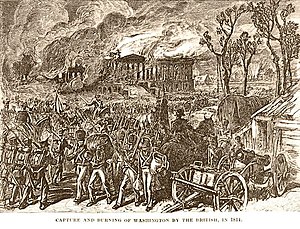

Burning of Washington 1814 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| N/A | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 4,250 [1] | 7,640 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 KIA Approximately 30 accidental deaths Several killed from weather [2] | Unknown | ||||||

The Burning of Washington was an incident of the War of 1812 between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the United States of America. On August 24, 1814, a British force occupied Washington, D.C. and set fire to many public buildings following the American defeat at the Battle of Bladensburg. The facilities of the U.S. government, including the White House and U.S. Capitol, were largely destroyed[citation needed], though strict discipline and the British commander's orders to burn only public buildings are credited with preserving the city's private buildings. This has been the only time since the Revolutionary War that a foreign power has captured and occupied the United States capital.[3]

Reasons for the attack

Historians[who?] assert that the attack was in retaliation for the American burning and looting of York (now Toronto) during the Battle of York in 1813, and the burning down of the buildings of the Legislative Assembly there. The British Army commanders said they chose to attack Washington "on account of the greater political effect likely to result".[4]

Governor-General Sir George Prevost of Canada wrote to the Admirals in Bermuda calling for a retaliation for the American sacking of York and requested their permission and support in the form of provision of naval resources. At the time, it was considered against the civilized laws of war to burn a non-military facility and the Americans had not only burned the Parliament but also looted and burned the Governor's mansion, private homes and warehouses.[5]

Further proof of the intention was that after the limited British burning of some public facilities, the British left. There was no territory that they wanted to occupy, no military facility that they had planned to attack.

Events

On August 24, 1814, the advance guard of British troops made a march to Capitol Hill. General Robert Ross sent a party under a flag of truce to agree to terms, but they were attacked by partisans from a house at the corner of Maryland Avenue, Constitution Avenue, and Second Street NE. This was to be the only resistance the soldiers met. The house was burned, and the Union Flag raised over Washington.[citation needed]

The buildings housing the Senate and House of Representatives—construction on the central rotunda of the Capitol had not yet begun—were set ablaze not long after. The interiors of both buildings, including the Library of Congress, were destroyed, although the thick walls and a torrential rainfall preserved their exteriors. (Thomas Jefferson later sold his library to the government to restock the Library of Congress.) The next day Admiral Cockburn entered the building of the D.C. newspaper, National Intelligencer, intending to burn it down; however, a group of neighborhood women persuaded him not to because they were afraid the fire would spread to their neighboring houses. Cockburn wanted to destroy the newspaper because they had written so many negative items about him, branding him as "The Ruffian." Instead he ordered his troops to tear the building down brick by brick making sure that they destroyed all the "C" type so that no more pieces mentioning his name could be printed [citation needed].

White House

The troops then turned northwest up Pennsylvania Avenue toward the White House. After the government officials fled, Dolley Madison remained behind with the White House slaves to save valuables from the British. One of Madison's slaves, Paul Jennings was an eyewitness who wrote:

"It has often been stated in print, that when Mrs. Madison escaped from the White House, she cut out from the frame the large portrait of Washington (now in one of the parlors there), and carried it off. This is totally false. She had no time for doing it. It would have required a ladder to get it down. All she carried off was the silver in her reticule, as the British were thought to be but a few squares off, and were expected every moment."[6]

Jennings said that the people who saved the painting and removed the objects were:

"John Susé (a Frenchman, then door-keeper, and still living) and Magraw, the President's gardener, took it down and sent it off on a wagon, with some large silver urns and such other valuables as could be hastily got hold of. After this he said, "When the British did arrive, they ate up the very dinner, and drank the wines, &c., that I had prepared for the President's party."[6]

Dolley Madison did not save the painting herself, but she was the one who ordered it to be done.

The soldiers then burnt the house, and fuel was added to the fires that night to ensure they would continue burning into the next day; the smoke was reportedly visible as far away as Baltimore and the Patuxent River.[citation needed]

In 2009 there was a White House ceremony to honour the efforts of Paul Jennings in rescuing the painting of George Washington. "A dozen descendants of Jennings came to Washington, to visit the White House. For a few precious minutes, they were able to look at the painting their relative helped save."[7] Of those invited, one of them gave an interview to NPR and that Jennings later purchased his freedom, and that "We were able to take a family portrait in front of the painting, which was for me one of the high points."[8]

Other Property in Washington

The British also burned the United States Treasury Building and other public buildings. Much of the historic Washington Navy Yard, founded by Thomas Jefferson and the first federal installation in the United States, was burned by the Americans to prevent capture of stores and ammunition, as well as the 44-gun frigate USS Columbia which was then being built. The Navy Yard's Latrobe Gate, Quarters A, and Quarters B were the only buildings to escape destruction.[9][10] The United States Patent Office building was saved by the efforts of William Thornton—Architect of the Capitol and then superintendent of patents—who convinced the British of the importance of its preservation. Also spared were the Marine Barracks, which some attribute as a gesture of respect for their conduct at Bladensburg.[11] However, Alexandria was captured by the British during the raid on Alexandria, although a deal with the mayor kept that town from being burnt.[12]

In the afternoon of August 25, General Ross sent two hundred men to secure a fort on Greenleaf's Point. The fort, later known as Fort McNair, had already been destroyed by the Americans, but 150 barrels of gunpowder remained. While the British were attempting to destroy the powder by dropping the barrels into a well, the powder ignited. As many as thirty men were killed in the explosion, and many others were maimed.[13] The attack cost the Navy one man killed and six wounded, of whom, the one fatality and three of the wounded were from the Corps of Colonial Marines.[14]

Less than a day after the attack began, a sudden tornado passed through part of the city, killing British troops and American civilians alike, tossing cannons, and putting out most of the fires.[15] This forced the British troops to return to their ships, many of which were badly damaged by the storm, and so the actual occupation of Washington lasted about 26 hours. President Madison and the rest of the government quickly returned to the city.[citation needed]

Reconstruction

The thick sandstone walls of the White House and Capitol survived, although scarred with smoke and scorch marks. Fearful of the loss of the capital, Washington businessmen financed the construction of the Old Brick Capitol, where Congress met while the Capitol was reconstructed from 1815 to 1819. Reconstruction of the White House also began in early 1815 and was finished in time for President James Monroe's inauguration in 1817. Madison resided in The Octagon House for the remainder of his term.[citation needed]

References

- ^ "Burning of Washington, D.C.;Chesapeake Campaign". The War of 1812. genealogy, Inc. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ Myatt, Kevin (August 26, 2006). "Did tornado wreak havoc on War of 1812?". The Roanoke Times. Roanoke, VA. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ The War of 1812: A FORGOTTEN CONFLICT, Donald R. Hickey, University of Illinois Press (October 1, 1990)

- ^ Roger Morriss, Cockburn and the British Navy in Transition: Admiral Sir George Cockburn, 1772-1853 (University of Exeter Press, 1997), P. 104

- ^ Charles W. Humphries, "The Capture of York", in Zaslow, p.264

- ^ a b Jennings, Paul (1865). A colored man's reminiscences of James Madison. Brooklyn, NY: G.C. Beadle. pp. 14–15.

- ^ Gura, Davie. "Descendants Of A Slave See The Painting He Saved". The Two-Way. NPR. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ "Descendant Of White House Slave Shares Legacy". NPR. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory — Nomination Form" (PDF). National Capital Planning Commission. National Park Service. June 30, 1972. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory — Nomination Form" (PDF). National Park Service. November 1, 1975. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ Powers, Rod. "Marine Corps Legends". about.com. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

{{cite web}}: External link in|author= - ^ Landry, Peter (2009). Settlement, Revolution & War. Bloomington, IL: Trafford Publishing. p. 255. ISBN 9781425187910.

- ^ George, Christopher T. Terror on the Chesapeake: The War of 1812 on the Bay White Mane Books (2000), p. 111

- ^ "No. 16939". The London Gazette. 27 September 1814.

- ^ "NWS Sterling, VA - D.C. Tornado Events". National Weather Service Eastern Region Headquarters. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

Further reading

- Gura, David Descendants Of A Slave See The Painting He Saved NPR, August 24, 2009.

- Jennings, Paul. A Colored Man's Reminiscences of James Madison Brookyn, George C. Beadle, 1865. pgs 12-14.

- Latimer, Jon. 1812: War with America, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-674-02584-9

- Martin, John. "The British Are Coming: Historian Anthony Pitch Describes Washington Ablaze," LC Information Bulletin, September 1998

- Pack, A. James. The Man Who Burned The White House, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1987. ISBN 0-87021-420-9

- Phelan, Mary Kay. The Burning of Washington: August 1814, Ty Crowell Co, 1975. ISBN 0-690-00486-9

- Pitch, Anthony S. The Burning of Washington, White House History Magazine, Fall 1998

- Pitch, Anthony S. The Burning of Washington, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2000. ISBN 1-55750-425-3

- Siegel, Robert Descendant Of White House Slave Shares Legacy NPR, August 24, 2009.

- Whitehorne, Joseph A. The Battle for Baltimore: 1814 (1997)

- Listing by surname of Royal Marines (2nd Battn, 3rd Battn, Colonial Marines) paid prize money for participating in the attack on Washington