The dragon (Beowulf): Difference between revisions

boost the dragon |

|||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

==Story== |

==Story== |

||

After his battles against [[Grendel]] and [[Grendel's mother|his mother]], Beowulf returns to his homeland from [[Heorot]] and becomes king of the Geats. Fifty years pass with Beowulf leading as a wise king, when a rampaging dragon (called a [[Wyrm (disambiguation)|wyrm]] in the Old English) begins to attack the countryside. It measures 50 feet long and possesses a pair of formidable horns and razor sharp teeth and claws. The reason of its |

After his battles against [[Grendel]] and [[Grendel's mother|his mother]], Beowulf returns to his homeland from [[Heorot]] and becomes king of the Geats. Fifty years pass with Beowulf leading as a wise king, when a rampaging dragon (called a [[Wyrm (disambiguation)|wyrm]] in the Old English) begins to attack the countryside. It measures 50 feet long and possesses a pair of formidable horns and razor sharp teeth and claws. The reason of its aggression is revenge; a slave came upon its lair and stole a golden cup from the massive hoard of treasure it guards; this cup is its favourite. Beowulf and a troop of his men set off into the forest find the dragon's lair. They do so and find the dragon sleeping. Suddenly, it awakens and attacks Beowulf and his men with its claws, teeth and flaming breath. The men run away out of fear, leaving Beowulf and his young companion [[Wiglaf]] to slay the dragon. Beowulf receives a fatal wound from the dragon's horns but manages to stab the creature in the heart, killing it. Dying, Wiglaf shows Beowulf a portion of the dragon's hoard of gold: their reward. In his death-speech, Beowulf chooses Wiglaf as his successor giving to him the dragon's hoard and the kingship. |

||

== Background == |

== Background == |

||

Revision as of 17:16, 21 July 2011

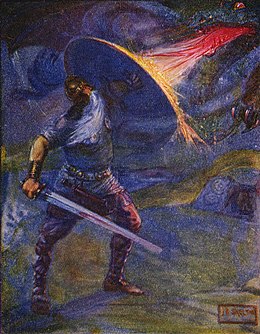

In the final act of the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf, the hero Beowulf fights a dragon, the third monster he encounters in the epic. Having returned home from Heorot, where he killed Grendel and Grendel's mother, Beowulf becomes king of the Geats, and rules wisely for 50 years. When a slave steals a jewelled cup from a dragonlair, the angry dragon brings destruction to the homes of Beowulf's people. With his thanes, Beowulf goes to slay the dragon; however faced with the dragon the thanes run away in fear. Only Wiglaf stays with Beowulf. The dragon wounds Beowulf fatally, but he manages to slay the dragon.

This depiction indicates the growing importance and stabilization of the modern concept of the dragon within European mythology. In fact, Beowulf is the first piece of English literature to present a dragonslayer. Although many motifs common to the Beowulf dragon existed in the Scandinavian and Germanic literature, the Beowulf poet was the first to combine features and present a distinctive fire-breathing dragon. The Beowulf dragon was copied in literature with similar motifs and themes surrounding the use of dragons in fiction such as in J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit, one of the forerunners of modern high fantasy.

The dragon fight, occurring at the end of the poem, is foreshadowed in earlier scenes. Beowulf's fight with the dragon symbolizes the fight against evil and destruction; in fighting the dragon the hero knows a failure on his part will cause destruction to his people. The scene is structured in thirds and ends with the deaths of the dragon and the hero.

Story

After his battles against Grendel and his mother, Beowulf returns to his homeland from Heorot and becomes king of the Geats. Fifty years pass with Beowulf leading as a wise king, when a rampaging dragon (called a wyrm in the Old English) begins to attack the countryside. It measures 50 feet long and possesses a pair of formidable horns and razor sharp teeth and claws. The reason of its aggression is revenge; a slave came upon its lair and stole a golden cup from the massive hoard of treasure it guards; this cup is its favourite. Beowulf and a troop of his men set off into the forest find the dragon's lair. They do so and find the dragon sleeping. Suddenly, it awakens and attacks Beowulf and his men with its claws, teeth and flaming breath. The men run away out of fear, leaving Beowulf and his young companion Wiglaf to slay the dragon. Beowulf receives a fatal wound from the dragon's horns but manages to stab the creature in the heart, killing it. Dying, Wiglaf shows Beowulf a portion of the dragon's hoard of gold: their reward. In his death-speech, Beowulf chooses Wiglaf as his successor giving to him the dragon's hoard and the kingship.

Background

Beowulf is the oldest extant heroic poem in English literature and the first to present a dragonslayer. The legend of the dragonslayer already existed in Norse sagas such as the tale of Sigurd and Fafnir, and the Beowulf poet incorporates motifs and themes common to dragonlore in the poem.[1] Beowulf is the first piece of Anglo-Saxon literature to feature a dragon and the poet would have had access to similar stories from Scandinavian oral tradition, although the original sources have been lost, which obscures the genesis of the Beowulf dragon.[2] Secular Germanic literature and the literature of hagiography featured dragons and dragon fights.[3] Although the dragons of hagiography were less fierce than the dragon in Beowulf, similarities exist in the stories such as presenting the journey to the dragon's lair, cowering spectators, and the sending of messages relaying the outcome of the fight.[4]

The dragon with his hoard is a common motif in early Germanic literature with the story existing to varying extents in the Norse and Icelandic sagas, but it is most notable in the Volsunga Saga and in Beowulf.[5] Beowulf preserves existing medieval dragon-lore, most notable in the extended digression recounting the Sigurd/Fafnir tale.[1] Nonetheless, comparative contemporary narratives did not have the complexity and distinctive elements written into Beowulf's dragon scene. Beowulf is a hero who previously killed two monsters. The scene includes extended flashbacks to the Geatish-Swedish wars, a detailed description of the dragon and the dragon-hoard, and ends with intricate funerary imagery.[6]

Beowulf scholar J.R.R. Tolkien considered the dragon in Beowulf to be one of only two real dragons in northern European literature, writing of it, "dragons, real dragons, essential both to the machinery and the ideas of a poem or tale, are actually rare. In northern literature there are only two that are significant .... we have but the dragon of the Völsungs, Fáfnir, and Beowulf's bane.[7] Furthermore, Tolkien believes the Beowulf poet emphasizes the monsters Beowulf fights in the poem, and he claims the dragon is as much of a plot device as anything. Tolkien expands on Beowulf's dragon in his own fiction, which indicates the lasting impact of the Beowulf poem.[1] Within the plot structure, however, the dragon functions differently in Beowulf than in Tolkien's fiction. The dragon fight ends Beowulf, while Tolkien uses the dragon motif (and the dragon's love for treasure) to trigger a chain of events in The Hobbit.[8]

Characterization

The Beowulf dragon is the earliest example in literature of the typical European dragon and first incidence of a fire breathing dragon.[9] But the characterization goes beyond fire breathing: the Beowulf dragon is described with Old English terms such as draca (dragon), and wyrm (worm, or serpent), and as a creature with a venomous bite.[10] Also, the Beowulf poet created a dragon with specific traits: a nocturnal treasure hoarding, inquisitive, vengeful, fire breathing creature.[11]

The fire likely symbolic of the hell-fire of the Devil, reminiscent of the monster in the Book of Job. In the Septuagint Bible, Job's monster is characterized as a draco: a creature that inhabits not only the land but the air and the water, and is identified with the Devil.[9] Job's dragon would have been accessible to the author of Beowulf, as a Christian symbol of evil, the "great monstrous adversary of God, man and beast alike."[12]

A study of German, Norse, Danish and Icelandic texts reveals three typical narratives for the dragonslayer: a fight for the treasure; a battle to save the slayer's people; or a fight to free a woman.[13] The characteristics of Beowulf's dragon appear to be specific to the poem; the poet may have melded together dragon motifs to create a dragon with specific traits to weave together the complicated plot of the narrative.[11]

Importance

The third act of the poem differs from the first two. Grendel and Grendel's mother receive little description, and are characterised as descendents of Cain—"[Grendel] had long lived in the land of monsters / since the creator cast them out / as the kindred of Cain."[14] They appear as humanoid, and the poet's rendition of them may have been to show them as giants, trolls or monsters common to the mythology of Northern Europe. The dragon, however, is plainly not human, creating a stark contrast to the other two antagonists.[15] Moreover, the dragon is overtly destructive by burning territory and the homes of the Geats—"the dragon began to belch out flames / and burn bright homesteads".[16][17]

Beowulf's fight with the dragon has been described variously as an act of altruism,[18] or an act of recklessness.[19] Furthermore, the dragon fight occurs in Beowulf's kingdom and ends in defeat, while the earlier monster fights occurred away from home and ended in victory. The dragon fight is foreshadowed in earlier events: Scyld Shefing's funeral and Sigmund's death by dragon, as recounted by a bard in Hrothgar's. Beowulf scholar Alexander writes in the introduction of his translation of the poem that the dragon-fight likely signifies Beowulf's (and by extension, society's) battle against evil.[20] The people's fate depends on the outcome of the fight between the hero and the dragon with the hero accepting responsibility to go into battle knowingly facing death.[21]

Beowulf's death presages "warfare, death, and darkness" for his Geats.[22] The dragon's hoard is a vestige of a previous society "wiped out by war", and left by a survivor, whose imagined elegy foreshadows Beowulf's elegy.[23] In fact, before he faces the dragon, Beowulf remembers his childhood and the wars the Geats endured, which foreshadows the fate his people will face upon his death.[24] An embattled society without "social cohesion" is represented by the avarice of the "dragon jealously guarding its gold hoard",[25] as the elegy for Beowulf becomes an elegy for the entire culture.[26] The dragon's hoard is representative of a people lost to time, which is juxtaposed against the Geatish people, whose history is new, fresh and fleeting.[27] As king of his people, Beowulf defends them against the dragon; and when his thanes desert him, the poem shows the disintegration of a "heroic society" which "depends upon the honouring of mutual obligations between lord and thane."[28]

Wiglaf remains loyal to his king and unlike the other men, stays to confront the dragon. The parallel in the story lies with the similarity to Beowulf's hero Sigemund and his companion; Wiglaf is a younger companion to Beowulf and in his courage shows himself to be Beowulf's successor.[29][30] The presence of a companion is seen as a motif in other dragon stories, but the Beowulf poet breaks hagiographic tradition with the hero's suffering (hacking, burning, stabbing) and subsequent death.[31] Moreover, the dragon is vanquished through Wiglaf's actions—although Beowulf dies fighting the dragon, the dragon dies at the hand of the companion.[28]

The dragon battle is structured in thirds: the preparation for the battle; the events prior to the battle; and the battle itself. Wiglaf kills the dragon halfway through the scene, Beowulf's death occurs "after two-thirds" of the scene,[32] and the dragon attacks Beowulf three times.[33] Ultimately, as Tolkien writes, the death by dragon "is the right end for Beowulf" for he claims "a man can but die upon his death-day."[34]

Legacy

J.R.R. Tolkien used the dragon story of Beowulf as a template for Smaug of The Hobbit. In each case the dragon's hoard is disturbed; the dragon flies into a rage; the dragon is slain by a human (as opposed to dwarf, elf, or other creature, in the case of The Hobbit); and one character disturbs the dragon while another does the slaying.[35]

The tale of Beowulf was translated and rewritten in prose as a children's story by Rosemary Sutcliffe in 1961, titled Dragon Slayer.[36]

References

- Footnotes

- ^ a b c Evans, pp. 25–26

- ^ Rauer, p.135

- ^ Rauer, p. 4

- ^ Rauer, p. 74

- ^ Evans, pp. 29

- ^ Rauer, p.32

- ^ Tolkien, p. 4

- ^ Evans, p. 30

- ^ a b Brown, Alan K. (1980). "The firedrake in Beowulf". Abstract from Neophilologus. Springer Netherlands. pp. 439–460. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ^ Rauer, p. 32, p .63

- ^ a b Rauer, p. 35

- ^ Rauer, p. 52

- ^ Evans, p.28

- ^ Alexander, p. 6

- ^ Mellinkoff,Ruth. Cain's monstrous progeny in Beowulf: part I, Noachic tradition Anglo-Saxon England (1979), 8 : 143–162 Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2010-05-18

- ^ Heaney, p.157

- ^ Rauer, p. 74-75

- ^ Clark, 43

- ^ Crossley-Holland, p. xiv

- ^ Alexander, pp. xxiv-xxv

- ^ Alexander, pp. xxx-xxxv

- ^ Crossley-Holland, p. vii

- ^ Crossley-Holland, p. xvi

- ^ Crossley-Holland, p. xvii

- ^ Crossley-Holland, p. xix

- ^ Crossley-Holland, p. xxvi

- ^ Clark, Handbook, p. 289

- ^ a b Alexander, p. xxxvi

- ^ Crossley-Holland, p. xviii

- ^ Beowulf and some fictions of the Geatish succession by Frederick M. Biggs.

- ^ Raurer, p. 74

- ^ Rauer, p. 31

- ^ Alexander, p. xxv

- ^ Tolkien, p. 14

- ^ Clark, p. 31

- ^ Alexander, p. xxiv

Sources

- Alexander, Michael. Beowulf: a verse translation (2003 ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 9780140449310. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_chapter=and|month=(help) - Clark, George (1998). "The Hero and the Theme". In Bjork, Robert E.; Niles, John D. (eds.). A Beowulf Handbook. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803261501. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=,|trans_chapter=, and|chapterurl=(help) - Crossley-Holland, Kevin (1999). O'Donohue, Heather (ed.). Beowulf: The fight at Finnsburh. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192833204. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=and|trans_chapter=(help) - Evans, Jonathan (2000). "The Dragon-Lore of Middle-earth: Tolkien and Old English and Old Norse Tradition". In Clark, George; Timmons, Daniel (eds.). J.R.R. Tolkien and his literary resonances: views of [[Middle-earth]]. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30845-4. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=,|trans_chapter=, and|chapterurl=(help); URL–wikilink conflict (help) - Heaney, Seamus (2001). Beowulf: A New Verse Translation. Norton. ISBN 9780393320978. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Rauer, Christine (2003). Beowulf and the Dragon: Parallels and Analogues. Cambridge: Brewer. ISBN 0859915921. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=,|trans_chapter=, and|chapterurl=(help) - Tolkien, J.R.R. (25 November 1936). "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics". Sir Israel Gollancz Lecture 1936. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help)