Italian Eritrea: Difference between revisions

m →British occupation and the end of the colony: better link |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

|year_end = 1936 |

|year_end = 1936 |

||

|life_span = 1890 - 1936 |

|life_span = 1890 - 1936 |

||

|p1 = Khedivate of Egypt |

|||

|flag_p1 = Flag of Egypt 1826-1867 and 1881-1914.png |

|||

|s2 = Italian East Africa |

|s2 = Italian East Africa |

||

|flag_s2 = Flag of Italy (1861-1946).svg |

|flag_s2 = Flag of Italy (1861-1946).svg |

||

|image_flag = Flag of Italy (1861-1946).svg |

|image_flag = Flag of Italy (1861-1946).svg |

||

|flag = Flag of Eritrea |

|||

|image_coat = |

|image_coat = Eritrea-COA.PNG |

||

|symbol = |

|symbol = Coat of arms of Eritrea |

||

|image_map = Eritrea (Africa orthographic projection).svg |

|image_map = Eritrea (Africa orthographic projection).svg |

||

|image_map_caption = |

|image_map_caption = |

||

| Line 26: | Line 29: | ||

|leader2 = [[Pietro Badoglio]] |

|leader2 = [[Pietro Badoglio]] |

||

|year_leader2 = 1935-1936 |

|year_leader2 = 1935-1936 |

||

| currency = [[Eritrean tallero]] |

| currency = [[Eritrean tallero]]<br>(1890-1921)<br>[[Italian lira]]<br>(1921-1936) |

||

[[Italian lira]] (1921-1936) |

|||

| stat_year1 = 1936 |

| stat_year1 = 1936 |

||

| stat_area1 = 121000 |

| stat_area1 = 121000 |

||

Revision as of 01:53, 27 August 2011

Italian Eritrea Colonia Eritrea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 - 1936 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Status | Colony of Italy | ||||||

| Capital | Asmara | ||||||

| Governor | |||||||

• 1890 | Baldassarre Orero | ||||||

• 1935-1936 | Pietro Badoglio | ||||||

| Historical era | Scramble for Africa | ||||||

• Established | 1890 | ||||||

• Disestablished | 1936 | ||||||

| Area | |||||||

| 1936 | 121,000 km2 (47,000 sq mi) | ||||||

| Population | |||||||

• 1936 | 1,000,000 | ||||||

| Currency | Eritrean tallero (1890-1921) Italian lira (1921-1936) | ||||||

| |||||||

Italian Eritrea was the first colony of the Kingdom of Italy. It was created in 1890 (but the first Italian settlements were done in 1882 around Assab) and lasted officially until 1947.[1]

History

Acquisition of Assab and creation of the colony

From 1882 to 1941 Eritrea was ruled by the Kingdom of Italy. In those sixty years Eritrea was populated and developed - mainly in the area of Asmara - by groups of Italian colonists, who moved there from the beginning of the 20th century.

In 1869 the bay of Assab was bought by the Rubattino Shipping Company from the local Sultan, and was acquired by Italy (1882) who found the port inadequate for exploitation of its hinterlands, and came to use Assab as a coaling station.[2] During the twentieth century Assab became Ethiopia's main port.

The Italians took advantage of disorder in northern Ethiopia following the death of Emperor Yohannes IV in 1889 to occupy the highlands with General Oreste Baratieri and established their new colony, henceforth known as "Eritrea": they received recognition from Menelik II, Ethiopia's new Emperor.

The Italian possession of maritime areas previously claimed by Abyssinia/Ethiopia was formalized in 1889 with the signing of the Treaty of Wuchale with Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia (r. 1889–1913), after the defeat of Italy's general Baratieri by Ethiopia at the battle of Adua where Italy launched an effort to expand its possessions from Eritrea into the more fertile Abyssinian hinterland.

Menelik would later renounce the Wuchale Treaty as he had been tricked by the translators to agree to making the whole of Ethiopia into an Italian protectorate. However, he was forced by circumstance to live by the tenets of Italian sovereignty over Eritrea.

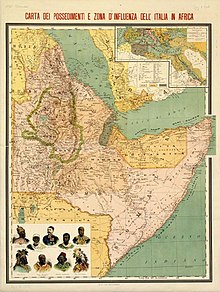

After 1890 the Italian government started to improve the new colony, called Colonia Primogenita, or first and preferred (in comparison to the other new colonies -like Italian Somalia and Italian Libya- being developed by the Italians in Africa).[3]

Around the turn of the century the Italian government promoted the arrival of a few dozen Italian families, who settled mainly in the area of Asmara and Massawa. The Italian Eritreans grew from 4,000 during World War I to nearly 100,000 (including the temporary military families) at the beginning of World War II.[4]

The Italians endorsed a huge expansion of Catholicism in Eritrea, insomuch that by 1940 nearly one third of all the Eritrean population was Catholic, mainly in Asmara and the area of Keren where many churches were built. Indeed the Cathedral of Asmara, built in 1922, was the main religious center of the Roman Catholicism in Eritrea: in the early 1940s Catholicism was the declared religion of more than 28% of people in the colony.[5]

Italian administration of Eritrea brought improvements in the medical and agricultural sectors of Eritrean society. For the first time in history the Eritrean poor population had access to sanitary and hospital services in the urban areas.

Furthermore, the Italians employed many Eritreans in public service (in particular in the police and public works departments) and oversaw the provision of urban amenities in Asmara and Massawa. In a region marked by cultural, linguistic, and religious diversity, a succession of Italian governors maintained a notable degree of unity and public order. The Italians also built many major infrastructural projects in Eritrea, including the Asmara-Massawa Cableway and the Eritrean Railway. The line was essentially destroyed by warfare in subsequent decades, but has been rebuilt between Massawa and Asmara. Vintage equipment is still used on this line.[6]

Italian Eritrea during the Fascist Era

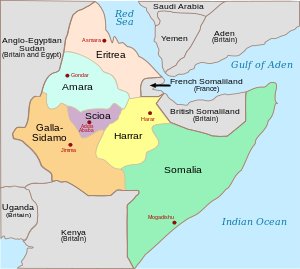

Benito Mussolini's rise to power in Italy in 1922 brought profound changes to the colonial government in Eritrea. After il Duce declared the birth of Italian Empire in May 1936, Italian Eritrea (enlarged with northern Ethiopia's regions) and Italian Somalia were merged with the just conquered Ethiopia in the new Africa Orientale Italiana new administrative subdivision. The Fascists in those years imposed harsh rule, that stressed the political ideology of colonialism in Eritrea in the name of a "new Roman Empire".

Eritrea was chosen by the Italian government to be the industrial center of the Italian East Africa.[7]

After the establishment of new transportation and communication methods in the country, the Italians also started to set up new factories, which in turn made due contribution in enhancing trade activities. The newly opened factories produced buttons, cooking oil, and pasta, construction materials, packing meat, tobacco, hide and other household commodities. In the year 1939, there were around 2,198 factories and most of the employees were Eritrean citizens, some even moved from the villages to work in the factories.The establishment of industries also made an increase in the number of both Italians and Eritreans residing in the cities. The number of Italians residing in the country increased from 4,600 to 75,000 in five years; and with the involvement of Eritreans in the industries, trade and fruit plantation was expanded across the nation, while some of the plantations were owned by Eritreans.[8]

The Italian government continued to implement agricultural reforms but primarily on farms owned by Italian colonists (exports of coffee boomed in the 1930s). In the area of Asmara there were in 1940 more than 2,000 small and medium sized industrial companies, concentrated in the areas of construction, mechanics, textiles, electricity and food processing. Consequently, the living standard of life in Eritrea in 1939 was considered one of the best of Africa for the Italian colonists and for the Eritreans.[9]

Mussolini's government considered the colony as a strategic base for future aggrandizement and ruled accordingly, using Eritrea as a base to launch its 1935–1936 campaign to colonize Ethiopia. Even in World War II the Italians used Eritrea to attack Sudan and occupy the Kassala area. Indeed, the best Italian colonial troops were the Eritrean Ascari, as stated by Italian Marshall Rodolfo Graziani and legendary officer Amedeo Guillet.[10]

According to the Italian census of 1939 the city of Asmara had a population of 98,000, of which 53,000 were Italians. This fact made Asmara the main "Italian town" of the Italian empire in Africa. Furthermore, because of the Italian architecture of the city, Asmara was called Piccola Roma (Little Rome).[11] In all Eritrea the Italians were 75,000 in that year.[12]

Asmara was known to be an exceptionally modern city, not only because of its architecture, but Asmara also had more traffic lights than Rome did when the city was being built. The city incorporates many features of a planned city. Indeed, Asmara was an early example of an ideal modern city created by architects, an idea which was introduced into many cities across the world, such as Brasilia, but which was not altogether popular. Features include designated city zoning and planning, wide treed boulevards, political areas and districts and space and scope for development. Asmara was not built for the Eritreans however; the Italians built it primarily for themselves. One unfortunate aspect of the city's planning was separate areas designated for Italians and Eritreans, each disproportionately sized.

The city has been regarded as "New Rome" or "Italy's African City" due to its quintessential Italian touch, not only for the architecture, but also for the wide streets, piazzas and coffee bars. While the boulevards are lined with palms and indigenous shiba'kha trees, there are numerable pizzerias and coffee bars, serving cappucinos and lattes, as well as ice cream parlours. The people in Asmara dress in a unique, yet African style. Asmara is also highly praised for its peaceful, crime-free environment. It is one of the cleanest cities of Africa.

Many industrial investments were endorsed by the Italians in the area of Asmara and Massawa, but the beginning of World War II stopped the blossoming industrialization of Eritrea.[13]

British occupation and the end of the colony

When the British army conquered Eritrea from the Italians in spring 1941, most of the infrastructures and the industrial areas were extremely damaged and the remaining ones (like the Asmara-Massawa Cableway) were successively removed and sent toward India and British Africa as a war booty.[14]

The following Italian guerrilla war was supported by many Eritrean colonial troops (like the "hero" of Eritrean independence, Hamid Idris Awate ) [15] until the Italian armistice in September 1943. Eritrea was placed under British military administration after the Italian surrender in World War II.

The Italians in Eritrea started to move away from the country after the defeat of the Kingdom of Italy by the Allies, and Asmara in the British census of 1949 already had only 17,183 Italian Eritreans on a total population of 127,579. Most Italian settlers left for Italy, with others to United States, Middle East, and Australia.

The British maintained initially the Italian administration of Eritrea, but the country soon started to be involved in a violent process of independence (from the British in the late forties and after 1952 from the Ethiopians, who annexed Eritrea in that year).

During the last years of World War II some Italian Eritreans like Dr. Vincenzo Di Meglio defended politically the presence of Italians in Eritrea and successively promoted the independence of Eritrea.[16] He went to Rome to participate in a Conference for the independence of Eritrea, promoted by the Vatican.

After the war Di Meglio was named Director of the "Commitato Rappresentativo Italiani dell' Eritrea" (CRIE). In 1947 he supported the creation of the "Associazione Italo-Eritrei" and the "Associazione Veterani Ascari", in order to get alliance with the Eritreans favorable to Italy in Eritrea.[17]

As a result of these creations, he cofounded the "Partito Eritrea Pro Italia" (Party of Shara Italy) in September 1947, an Eritrean political Party favorable to the Italian presence in Eritrea that obtained more than 200,000 inscriptions of membership in one single month.

Indeed the Italian Eritreans strongly rejected the Ethiopian annexation of Eritrea after the war: the Party of Shara Italy was established in Asmara in 1947 and the majority of the members were former Italian soldiers with many Eritrean Ascari (the organization was even backed up by the government of Italy).

The main objective of this party was Eritrea freedom, but they had a pre-condition that stated that before independence the country should be governed by Italy for at least 15 years (like happened with Italian Somalia).

With the Peace Treaty of 1947 Italy officially accepted the end of the colony. As a consequence the Italian community started to disappear, mainly after the Ethiopian government took control of Eritrea.

Governors of Italian Eritrea

- Baldassarre Orero from January 1890 to June 1890

- Antonio Gandolfi from June 1890 to February 1892

- Oreste Baratieri from February 1892 to February 1896

- Antonio Baldissera from February 1896 to December 1897

- Ferdinando Martini from February 1897 to March 1907

- Giuseppe Salvago Raggi from March 1907 to August 1915

- Giovanni Cerrina Feroni from August 1915 to September 1916

- Giacomo De Martino from September 1916 to July 1919

- Camillo De Camillis from July 1919 to November 1920

- Ludovico Pollera from November 1920 to April 1921

- Giovanni Cerrina Feroni from April 1921 to June 1923

- Giacopo Gasparini from June 1923 to June 1928

- Corrado Zoli from June 1928 to July 1930

- Riccardo Di Lucchesi from July 1930 to January 1935

- Emilio De Bono from January 1935 to November 1935

- Pietro Badoglio from November 1935 to May 1936

Gallery

-

Asmara Railway Station in 1938

-

"Fascist style" government building in Asmara

-

Railway Station of Keren (actually a Bus Station)

-

Governor's Palace, built in 1940 (actual President's Palace)

-

"Romanesque style" Catholic Church in Akrur, near Asmara

-

Downtown Asmara, called Piccola Roma, with typical Italian buildings

-

1939 Fiat Gas Station in Art deco style of Italian Asmara

-

Italian war cemetery in Keren

See also

- Italian Eritreans

- Italian Colonial Empire

- Asmara

- Cinema Impero

- Asmara President's Office

- Fiat Tagliero Building

- Vincenzo Di Meglio

- Eritrean Ascari

- Roman Catholicism in Eritrea

References

- ^ Essay on Italian Eritrea, done in 1953 (in Italian)

- ^ Edward Ullendorff, The Ethiopians: An Introduction to Country and People, second edition (London: Oxford University Press, 1965), p. 90. ISBN 0-19-285061-X.

- ^ The beginning of the Italian colony of Eritrea: Assab (in Italian)

- ^ http://www.ilcornodafrica.it/rds-01emigrazione.pdf Essay on Italian emigration to Eritrea (in Italian)

- ^ Bandini, Franco. Gli italiani in Africa, storia delle guerre coloniali 1882-1943 Chapter: Eritrea

- ^ Eritrean Railway

- ^ Italian industries in colonial Eritrea

- ^ Italian administration in Eritrea

- ^ Eritrea 1940

- ^ Amedeo Guillet in Eritrea

- ^ Italian architectural planification of Asmara (in Italian) p. 64-66

- ^ Italians in 1939 Eritrea

- ^ Italian industries and companies in Eritrea

- ^ Chapter on Eritrea under the British

- ^ Rosselli, Alberto. Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale. second chapter

- ^ Franco Bandini. Gli italiani in Africa, storia delle guerre coloniali 1882-1943 p. 67

- ^ http://www.ilcornodafrica.it/st-sci03.htm

Bibliography

- Bandini, Franco. Gli italiani in Africa, storia delle guerre coloniali 1882-1943. Longanesi. Milano, 1971.

- Bereketeab, R. Eritrea: The making of a Nation. Uppsala University. Uppsala, 2000.

- Lowe, C.J. Italian Foreign Policy 1870-1940. Routledge. 2002.

- Maravigna, Pietro. Come abbiamo perduto la guerra in Africa. Le nostre prime colonie in Africa. Il conflitto mondiale e le operazioni in Africa Orientale e in Libia. Testimonianze e ricordi. Tipografia L'Airone. Roma, 1949.

- Negash, Tekeste. Italian colonialism in Eritrea 1882-1941 (Politics, Praxis and Impact). Uppsala University. Uppsala, 1987.

- Rosselli, Alberto. Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale. Iuculano Editore. Pavia, 2007

- Mauri, Arnaldo. Eritrea's early stages in monetary and banking development, International Review of Economics, Vol. LI, N°. 4, 2004.

- Tuccimei, Ercole. La Banca d'Italia in Africa, Foreword by Arnaldo Mauri,Collana storica della Banca d'Italia, Laterza, Bari, 1999.

External links

- Old photos of Italian Eritrea

- Website with photos of Italian Asmara

- Postcards of Italian Asmara

- Website with documents, maps and photos of the Italians in Eritrea (in Italian)

- Detailed map of Eritrea in 1936 (click on the sections to enlarge)

- "1941-1951 The difficult years" (in Italian), showing the end of Italian Eritrea