The Fifty-Nine Icosahedra: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 240: | Line 240: | ||

|[http://www.georgehart.com/virtual-polyhedra/vrml/stellated_icosahedron_(26)_(5_color).wrl] |

|[http://www.georgehart.com/virtual-polyhedra/vrml/stellated_icosahedron_(26)_(5_color).wrl] |

||

||'''Ef<sub>1</sub>g<sub>1</sub>''' ||'''7 9 12''' ||28<BR>Third stellation ||9 ||{{sort|0826|Taf. VIII, Fig. 26}} |

||'''Ef<sub>1</sub>g<sub>1</sub>''' ||'''7 9 12''' ||28<BR>Third stellation ||9 ||{{sort|0826|Taf. VIII, Fig. 26}} |

||

| |

| [[Excavated dodecahedron]]. Topologically a [[regular polyhedron]]; see that article for more details. |

||

|[[Image:Third stellation of icosahedron facets.png|100px]] |

|[[Image:Third stellation of icosahedron facets.png|100px]] |

||

|[[Image:Third stellation of icosahedron.png|100px]] |

|[[Image:Third stellation of icosahedron.png|100px]] |

||

Revision as of 10:16, 30 August 2011

The Fifty Nine Icosahedra is a book written and illustrated by H. S. M. Coxeter, P. Du Val, H. T. Flather and J. F. Petrie. It enumerates the stellations of the regular convex or Platonic icosahedron, according to a set of rules put forward by J. C. P. Miller. There can also be more stellations, including one with Chiral Tetrahedral symmetry known as "Tetrahedron minus Icosahedron".

The book was completely reset and the plates redrawn for the Third Edition, with additional reference material and photographs, by K. and D. Crennell.

Authors' contributions

Miller's rules

Although Miller did not contribute to the book directly, he was a close colleague of Coxeter and Petrie. His contribution is immortalised in his set of rules for defining which stellation forms should be considered "properly significant and distinct":

- (i) The faces must lie in twenty planes, viz., the bounding planes of the regular icosahedron.

- (ii) All parts composing the faces must be the same in each plane, although they may be quite disconnected.

- (iii) The parts included in any one plane must have trigonal symmetry, without or with reflection. This secures icosahedral symmetry for the whole solid.

- (iv) The parts included in any plane must all be "accessible" in the completed solid (i.e. they must be on the "outside". In certain cases we should require models of enormous size in order to see all the outside. With a model of ordinary size, some parts of the "outside" could only be explored by a crawling insect).

- (v) We exclude from consideration cases where the parts can be divided into two sets, each giving a solid with as much symmetry as the whole figure. But we allow the combination of an enantiomorphous pair having no common part (which actually occurs in just one case).

Rules (i) to (iii) are symmetry requirements for the face planes. Rule (iv) excludes buried holes, to ensure that no two stellations look outwardly identical. Rule (v) prevents any disconnected compound of simpler stellations.

Coxeter

Coxeter was the main driving force behind the work. He carried out the original analysis based on Miller's rules, adopting a number of techniques such as combinatorics and abstract graph theory whose use in a geometrical context was then novel.

He observed that the stellation diagram comprised many line segments. He then developed procedures for manipulating combinations of the adjacent plane regions, to formally enumerate the combinations allowed under Miller's rules.

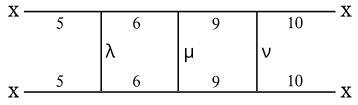

His graph, reproduced here, shows the connectivity of the various faces identified in the stellation diagram (see below). The Greek symbols represent sets of possible alternatives:

- λ may be 3 or 4

- μ may be 7 or 8

- ν may be 11 or 12

Du Val

Du Val devised a symbolic notation for identifying sets of congruent cells, based on the observation that they lie in "shells" around the original icosahedron. Based on this he tested all possible combinations against Miller's rules, confirming the result of Coxeter's more analytical approach.

Flather

Flather's contribution was indirect: he made card models of all 59. When he first met Coxeter he had already made many stellations, including some "non-Miller" examples. He went on to complete the series of fifty-nine, which are preserved in the mathematics library of Cambridge University, England. The library also holds some non-Miller models, but it is not known whether these were made by Flather or by Miller's later students. [1]

Petrie

John Flinders Petrie was a lifelong friend of Coxeter and had a remarkable ability to visualise four-dimensional geometry. He and Coxeter had worked together on many mathematical problems. His direct contribution to the fifty nine icosahedra was the exquisite set of three-dimensional drawings which provide much of the fascination of the published work.

The Crennells

For the Third Edition, Kate and David Crennell completely reset the text and redrew the illustrations and Plates. They also added a reference section containing tables, diagrams, and photographs of some of the Cambridge models (which at that time were all thought to be Flather's). It includes an index of all 59, numbered sequentially as they appear in the book. A few errors crept into the editing process, such as in some of the Plates and in the annotations to Fig.7. A PDF file of corrected pages is available online.

List of the fifty nine icosahedra

Before Coxeter, only Brückner and Wheeler had recorded any significant sets of stellations, although a few such as the great icosahedron had been known for longer. Since publication of The 59, Wenninger published instructions on making models of some; his scheme has become widely referenced, although he only recorded a few stellations.

Notes on the list

Index numbers are the Crennells' unless otherwise stated:

Crennell

- In the index numbering added to the Third Edition by the Crennells, the first 32 forms (indices 1-32) are reflective models, and the last 27 (indices 33-59) are chiral with only the right-handed forms listed. This follows the order in which the stellations are depicted in the book.

VRML

- Links are to George Hart's VRML 3D graphics files.

Cells

- In Du Val's notation, each shell is identified in bold type, working outwards, as a, b, c, ..., h with a being the original icosahedron. Some shells subdivide into two types of cell, for example e comprises e1 and e2. The set f1 further subdivides into right- and left-handed forms, respectively f1 (plain type) and f1 (italic). Where a stellation has all cells present within an outer shell, the outer shell is capitalised and the inner omitted, for example a + b + c +e1 is written as Ce1.

Faces

- All of the stellations can be specified by a stellation diagram. In the diagram shown here, the numbered colors indicate the regions of the stellation diagram which must occur together as a set, if full icosahedral symmetry is to be maintained. The diagram has 13 such sets. Some of these subdivide into chiral pairs (not shown), allowing stellations with rotational but not reflexive symmetry. In the table, faces which are seen from underneath are indicated by an apostrophe, for example 3'.

Wenninger

- The index numbers and the numbered names were allocated arbitrarily by Wenninger's publisher according to their occurrence in his book Polyhedron models and bear no relation to any mathematical sequence. Only a few of his models were of icosahedra. His names are given in shortened form, with "... of the icosahedron" left off.

Wheeler

- Wheeler found his figures, or "forms" of the icosahedron, by selecting line segments from the stellation diagram. He carefully distinguished this from Kepler's classical stellation process. Coxeter et al. ignored this distinction and referred to all of them as stellations.

Brückner

- Brückner made and photographed models of many polyhedra, only a few of which were icosahedra. Taf. is an abbreviation of Tafel, German for plate.

Remarks

- No. 8 was named the echidnahedron after an imagined similarity to the spiny anteater or echidna. This usage is independent of Kepler's description of his regular star polyhedra as his echidnae.

Table of the fifty nine icosahedra

| Crennell | VRML | Cells | Faces | Wenninger | Wheeler | Brückner | Remarks | Face | 3D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [1] | A | 0 | 4 Icosahedron |

1 | The Platonic icosahedron |

|

| |

| 2 | [2] | B | 1 | 26 Triakis icosahedron |

2 | Taf. VIII, Fig. 2 | First stellation of the icosahedron, small triambic icosahedron, or Triakisicosahedron |

|

|

| 3 | [3] | C | 2 | 23 Compound of five octahedra |

3 | Taf. IX, Fig. 6 | Regular compound of five octahedra |

|

|

| 4 | [4] | D | 3 4 | 4 | Taf. IX, Fig.17 |

|

| ||

| 5 | [5] | E | 5 6 7 | ||||||

| 6 | [6] | F | 8 9 10 | 27 Second stellation |

19 |

|

| ||

| 7 | [7] | G | 11 12 | 41 Great icosahedron |

11 | Taf. XI, Fig. 24 | Great icosahedron |

|

|

| 8 | [8] | H | 13 | 42 Final stellation |

12 | Taf. XI, Fig. 14 | Final stellation of the icosahedron or Echidnahedron |

|

|

| 9 | [9] | e1 | 3' 5 | 37 Twelfth stellation |

|

| |||

| 10 | [10] | f1 | 5' 6' 9 10 | ||||||

| 11 | [11] | g1 | 10' 12 | 29 Fourth stellation |

21 |

|

| ||

| 12 | [12] | e1f1 | 3' 6' 9 10 |

| |||||

| 13 | [13] | e1f1g1 | 3' 6' 9 12 | 20 | |||||

| 14 | [14] | f1g1 | 5' 6' 9 12 | ||||||

| 15 | [15] | e2 | 4' 6 7 | ||||||

| 16 | [16] | f2 | 7' 8 | 22 | |||||

| 17 | [17] | g2 | 8' 9' 11 | ||||||

| 18 | [18] | e2f2 | 4' 6 8 | ||||||

| 19 | [19] | e2f2g2 | 4' 6 9' 11 | ||||||

| 20 | [20] | f2g2 | 7' 9' 11 | 30 Fifth stellation |

|

| |||

| 21 | [21] | De1 | 4 5 | 32 Seventh stellation |

10 |

|

| ||

| 22 | [22] | Ef1 | 7 9 10 | 25 Compound of ten tetrahedra |

8 | Taf. IX, Fig. 3 | Regular compound of ten tetrahedra |

|

|

| 23 | [23] | Fg1 | 8 9 12 | 31 Sixth stellation |

17 | Taf. X, Fig. 3 |

|

| |

| 24 | [24] | De1f1 | 4 6' 9 10 | ||||||

| 25 | [25] | De1f1g1 | 4 6' 9 12 | ||||||

| 26 | [26] | Ef1g1 | 7 9 12 | 28 Third stellation |

9 | Taf. VIII, Fig. 26 | Excavated dodecahedron. Topologically a regular polyhedron; see that article for more details. |

|

|

| 27 | [27] | De2 | 3 6 7 | 5 | |||||

| 28 | [28] | Ef2 | 5 6 8 | 18 | Taf.IX, Fig. 20 |

|

| ||

| 29 | [29] | Fg2 | 10 11 | 33 Eighth stellation |

14 |

|

| ||

| 30 | [30] | De2f2 | 3 6 8 | 34 Ninth stellation |

13 |

|

| ||

| 31 | [31] | De2f2g2 | 3 6 9' 11 | ||||||

| 32 | [32] | Ef2g2 | 5 6 9' 11 | ||||||

| 33 | [33] | f1 | 5' 6' 9 10 | 35 Tenth stellation |

|

| |||

| 34 | [34] | e1f1 | 3' 5 6' 9 10 | 36 Eleventh stellation |

|

| |||

| 35 | [35] | De1f1 | 4 5 6' 9 10 | ||||||

| 36 | [36] | f1g1 | 5' 6' 9 10' 12 | ||||||

| 37 | [37] | e1f1g1 | 3' 5 6' 9 10' 12 | 39 Fourteenth stellation |

|

| |||

| 38 | [38] | De1f1g1 | 4 5 6' 9' 10' 12 | ||||||

| 39 | [39] | f1g2 | 5' 6' 8' 9' 10 11 | ||||||

| 40 | [40] | e1f1g2 | 3' 5 6' 8' 9' 10 11 | ||||||

| 41 | [41] | De1f1g2 | 4 5 6' 8' 9' 10 11 | ||||||

| 42 | [42] | f1f2g2 | 5' 6' 7' 9' 10 11 | ||||||

| 43 | [43] | e1f1f2g2 | 3' 5 6' 7' 9' 10 11 | ||||||

| 44 | [44] | De1f1f2g2 | 4 5 6' 7' 9' 10 11 | ||||||

| 45 | [45] | e2f1 | 4' 5' 6 7 9 10 | 40 Fifteenth stellation |

|

| |||

| 46 | [46] | De2f1 | 3 5' 6 7 9 10 | ||||||

| 47 | [47] | Ef1 | 5 6 7 9 10 | 24 Compound of five tetrahedra |

7 (6: left handed) |

Taf. IX, Fig. 11 | Regular Compound of five tetrahedra (right handed) |

|

|

| 48 | [48] | e2f1g1 | 4' 5' 6 7 9 10' 12 | ||||||

| 49 | [49] | De2f1g1 | 3 5' 6 7 9 10' 12 | ||||||

| 50 | [50] | Ef1g1 | 5 6 7 9 10' 12 | ||||||

| 51 | [51] | e2f1f2 | 4' 5' 6 8 9 10 | 38 Thirteenth stellation |

|

| |||

| 52 | [52] | De2f1f2 | 3 5' 6 8 9 10 | ||||||

| 53 | [53] | Ef1f2 | 5 6 8 9 10 | 15 (16: left handed) |

|||||

| 54 | [54] | e2f1f2g1 | 4' 5' 6 8 9 10' 12 | ||||||

| 55 | [55] | De2f1f2g1 | 3 5' 6 8 9 10' 12 | ||||||

| 56 | [56] | Ef1f2g1 | 5 6 8 9 10' 12 | ||||||

| 57 | [57] | e2f1f2g2 | 4' 5' 6 9' 10 11 | ||||||

| 58 | [58] | De2f1f2g2 | 3 5' 6 9' 10 11 | ||||||

| 59 | [59] | Ef1f2g2 | 5 6 9' 10 11 |

See also

- List of Wenninger polyhedron models – Wenninger's book Polyhedron models included 21 of these stellations.

- Solids with icosahedral symmetry

Notes

References

- Brückner, Max (1900). Vielecke und Vielflache: Theorie und Geschichte. Leipzig: B.G. Treubner. ISBN 978-1418165901. Template:De icon

- WorldCat English: Polygons and Polyhedra: Theory and History. Photographs of models: Tafel VIII (Plate VIII), etc. High res. scans.

- Coxeter, Harold Scott MacDonald; Du Val, P.; Flather, H. T.; Petrie, J. F. (1999), The fifty-nine icosahedra (3rd ed.), Tarquin, ISBN 978-1-899618-32-3, MR676126 (1st Edn University of Toronto (1938))

- Wenninger, Magnus J., Polyhedron models; Cambridge University Press, 1st Edn (1983), Ppbk (2003). ISBN 978-0521098595.

- A. H. Wheeler, Certain forms of the icosahedron and a method for deriving and designating higher polyhedra, Proc. Internat. Math. Congress, Toronto, 1924, Vol. 1, pp 701–708.