Looting: Difference between revisions

Luckas-bot (talk | contribs) m r2.7.1) (Robot: Adding be-x-old:Марадэрства |

DoctorKubla (talk | contribs) Merged content from War loot |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

===War looting=== |

===War looting=== |

||

[[File:Spaanse Furie - De plundering van Mechelen door de hertog van Alba in 1572 (Frans Hogenberg).jpg|thumb|The sacking and looting of [[Mechelen]] by the Spanish troops led by the [[Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba|Duke of Alba]], 2 October 1572.]] |

[[File:Spaanse Furie - De plundering van Mechelen door de hertog van Alba in 1572 (Frans Hogenberg).jpg|thumb|The sacking and looting of [[Mechelen]] by the Spanish troops led by the [[Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba|Duke of Alba]], 2 October 1572.]] |

||

{{main|War loot}} |

|||

Looting by a victorious army during war has been common practice throughout recorded history. For foot soldiers, it was viewed as a way to supplement their often meagre income<ref name=hsc>Hsi-sheng Chi, ''Warlord politics in China, 1916-1928'', Stanford University Press, 1976, ISBN 0804708940, str. 93</ref> and was part of the celebration of victory. On higher levels, the proud exhibition of loot was an integral part of the typical [[Roman triumph]], and [[Genghis Khan]] was not unusual in proclaiming that "the greatest happiness was to vanquish, devastate and rob one's enemies".<ref>[http://thinkexist.com/quotation/the-greatest-happiness-is-to-vanquish-your/1393183.html Thinkexist.com], Genghis Khan quotes</ref>}} |

|||

Looting originally referred primarily to the plundering of villages and cities not only by victorious troops during warfare, but also by civilian members of the community (for example, see ''[[War and Peace]]'',<ref>[http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/2600 War and Peace by graf Leo Tolstoy - Project Gutenberg<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> which describes widespread looting by [[Moscow]]'s citizens before [[Napoleon]]'s troops enter the town, and looting by French troops elsewhere; also note the [[Nazi plunder|looting of art treasures by the Nazis]] during WWII<ref>{{cite news| url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/arts/2291481.stm | work=BBC News | title=Nazi loot claim 'compelling' | date=October 2, 2002 | accessdate=May 11, 2010}}</ref>). [[Piracy]] is a form of looting organized by ships on the high seas outside the control of a sovereign government. The [[Hague Conventions (1899 and 1907)|Hague Convention of 1907]] and the [[Fourth Geneva Convention]] of 1949, both explicitly ban "pillage" by hostile armies. A common way to avoid this is to establish [[Custodian of Enemy Property]], which handle the property until it can be returned. |

|||

In warfare in ancient times, the spoils of war included the defeated populations, which were often enslaved, and the women and children, who were often absorbed into the victorious country's population.<ref>John K. Thorton, ''African Background in American Colonization'', in ''The Cambridge economic history of the United States'', Stanley L. Engerman, Robert E. Gallman (ed.), Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0521394422, p.87. "African states waged war to acquire slaves [...] raids that appear to have been more concerned with obtaining loot (including slaves) than other objectives."</ref><ref>Sir John Bagot Glubb, ''The Empire of the Arabs'', Hodder and Stoughton, 1963, p.283. "...thousand Christian captives formed part of the loot and were subsequently sold as slaves in the markets of Syria".</ref> In other pre-modern societies, objects made of precious metals were the preferred target of war looting, largely because of their easy portability. In many cases looting was an opportunity to obtain treasures that otherwise would not have been obtainable. Since the 18th century, [[looted art|works of art]] have increasingly become a popular target. In the 1930s and even more so during [[World War II]], [[Nazi Germany]] engaged in large scale and organized [[Nazi plunder|looting of art and property]].<ref>{{pl icon}} J. R. Kudelski, ''Tajemnice nazistowskiej grabieży polskich zbiorów sztuki'', Warszawa 2004.</ref><ref>{{cite news| url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/arts/2291481.stm | work=BBC News | title=Nazi loot claim 'compelling' | date=October 2, 2002 | accessdate=May 11, 2010}}</ref> |

|||

Looting, combined with poor [[military discipline]], has occasionally been an army's downfall. In other cases, for example the [[Wahhabi sack of Karbala]], loot has financed further victories.<ref>Wayne H. Bowen, ''The History of Saudi Arabia'', Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008, ISBN 0313340129, [http://books.google.com/books?id=S6J2Q3TlJpMC&pg=PA73&lpg=PA73&dq=1805+saudi+karbala&source=bl&ots=z7xkfvrX_x&sig=yg1NCeie86areM74Tp0N2ROwUf8&hl=en&ei=f4cCTbnlLsL38AaO_dTrAg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBcQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=1805%20saudi%20karbala&f=false Google Print, p.73]</ref> Not all looters in wartime are conquerors; the looting of [[Vistula Land]] by its retreating defenders in 1915<ref>{{pl icon}} Andrzej Garlicki, ''Z dziejów Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej'', Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 1986, ISBN 8302022454, p. 147</ref> was among the factors sapping the loyalty of [[Poland in World War I]]. Local civilians can also take advantage of a breakdown of authority to loot public and private property, such as took place at the [[National Museum of Iraq]] in the course of the [[Iraq War]] in 2003.<ref>STEVEN LEE MYERS, [http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/24/world/middleeast/24museum.html Iraq Museum Reopens Six Years After Looting], New York Times, February 23, 2009</ref> The novel ''[[War and Peace]]'' describes widespread looting by [[Moscow]]'s citizens before [[Napoleon]]'s troops enter the town, and looting by French troops elsewhere. |

|||

===Archaeological removals=== |

===Archaeological removals=== |

||

| Line 37: | Line 41: | ||

During a disaster, police and military authorities are sometimes unable to prevent looting when they are overwhelmed by humanitarian or combat concerns, or cannot be summoned due to damaged communications infrastructure. Especially during natural disasters, some people find themselves forced to take what is not theirs in order to survive. How to respond to this is often a dilemma for the authorities.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/136582.stm | work=BBC News | title=Indonesian food minister tolerates looting | date=July 21, 1998 | accessdate=May 11, 2010}}</ref> In other cases, looting may be tolerated or even encouraged by authorities for political or other reasons. |

During a disaster, police and military authorities are sometimes unable to prevent looting when they are overwhelmed by humanitarian or combat concerns, or cannot be summoned due to damaged communications infrastructure. Especially during natural disasters, some people find themselves forced to take what is not theirs in order to survive. How to respond to this is often a dilemma for the authorities.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/136582.stm | work=BBC News | title=Indonesian food minister tolerates looting | date=July 21, 1998 | accessdate=May 11, 2010}}</ref> In other cases, looting may be tolerated or even encouraged by authorities for political or other reasons. |

||

The [[Fourth Geneva Convention]] of 1949 explicitly prohibits the looting of civilian property during wartime.<ref name=gen>E. Lauterpacht, C. J. Greenwood, Marc Weller, ''The Kuwait Crisis: Basic Documents'', Cambridge University Press, 1991, ISBN 0521463084, [http://books.google.com/books?id=5xVSkGtcT5YC&pg=PA154&dq=looting+geneva+Convention&hl=en&ei=_EgKTdnKCMiw4Aa1m-TZAQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6&ved=0CD4Q6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=looting geneva Convention&f=false Google Print, p.154]</ref> The [[Hague Convention of 1899]] (modified in 1954) obliges military forces not only to avoid destruction of enemy property, but to provide protection to it.<ref name=hague>Barbara T. Hoffman, ''Art and cultural heritage: law, policy, and practice'', Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0521857643 [http://books.google.com/books?id=yvXTcGC5CwQC&pg=PA57&dq=looting+Hague+Convention&hl=en&ei=y0gKTdWrG4WbOqqiwf8F&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCsQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=looting Hague Convention&f=false Google Print, p.57]</ref> Theoretically, to prevent such looting, unclaimed property is moved to the custody of the [[Custodian of Enemy Property]], to be handled until the return to its owner. |

|||

== Examples of looting == |

== Examples of looting == |

||

Revision as of 19:50, 1 April 2012

Looting (Hindi lūṭ, akin to Sanskrit luṭhati, [he] steals; also Latin latro, latronis "thief")—also referred to as sacking, plundering, despoiling, despoliation, and pillaging—is the indiscriminate taking of goods by force as part of a military or political victory, or during a catastrophe, such as during war,[1] natural disaster,[2] or rioting.[3] The term is also used in a broader sense, to describe egregious instances of theft and embezzlement, such as the "plundering" of private or public assets by corrupt or greedy authorities.[4] Looting is loosely distinguished from scavenging by the objects taken; scavenging implies taking of essential items such as food, water, shelter, or other material needed for survival while looting implies items of luxury or not necessary for survival such as art work, precious metals or other valuables. The proceeds of all these activities can be described as loot, plunder, or pillage.

Looting by type

War looting

Looting by a victorious army during war has been common practice throughout recorded history. For foot soldiers, it was viewed as a way to supplement their often meagre income[5] and was part of the celebration of victory. On higher levels, the proud exhibition of loot was an integral part of the typical Roman triumph, and Genghis Khan was not unusual in proclaiming that "the greatest happiness was to vanquish, devastate and rob one's enemies".[6]}}

In warfare in ancient times, the spoils of war included the defeated populations, which were often enslaved, and the women and children, who were often absorbed into the victorious country's population.[7][8] In other pre-modern societies, objects made of precious metals were the preferred target of war looting, largely because of their easy portability. In many cases looting was an opportunity to obtain treasures that otherwise would not have been obtainable. Since the 18th century, works of art have increasingly become a popular target. In the 1930s and even more so during World War II, Nazi Germany engaged in large scale and organized looting of art and property.[9][10]

Looting, combined with poor military discipline, has occasionally been an army's downfall. In other cases, for example the Wahhabi sack of Karbala, loot has financed further victories.[11] Not all looters in wartime are conquerors; the looting of Vistula Land by its retreating defenders in 1915[12] was among the factors sapping the loyalty of Poland in World War I. Local civilians can also take advantage of a breakdown of authority to loot public and private property, such as took place at the National Museum of Iraq in the course of the Iraq War in 2003.[13] The novel War and Peace describes widespread looting by Moscow's citizens before Napoleon's troops enter the town, and looting by French troops elsewhere.

Archaeological removals

Looting can also refer to antiquities formerly removed from countries by outsiders, such as some of the contents of Egyptian tombs which were transported to museums in Europe.[14] Other examples include the obelisks of Pharaoh Amenhotep II, in the (Oriental Museum, University of Durham, United Kingdom), Pharaoh Ptolemy IX, (Philae Obelisk, in Wimborne, Dorset, United Kingdom). Recent controversies include the major part of the architectural sculptures adorning the Parthenon, often called the "Elgin Marbles", removed by Lord Elgin, later sold to the British Museum, and claimed by Greece that they should be returned.[15]

Looting of industry

In the aftermath of the Second World War Soviet forces had engaged in systematic plunder of Germany, including the Recovered Territories which were to be transferred to Poland, stripping it of valuable industrial equipment, infrastructure and factories and sending them to the Soviet Union.[16][17]

Measures against looting

During a disaster, police and military authorities are sometimes unable to prevent looting when they are overwhelmed by humanitarian or combat concerns, or cannot be summoned due to damaged communications infrastructure. Especially during natural disasters, some people find themselves forced to take what is not theirs in order to survive. How to respond to this is often a dilemma for the authorities.[18] In other cases, looting may be tolerated or even encouraged by authorities for political or other reasons.

The Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 explicitly prohibits the looting of civilian property during wartime.[19] The Hague Convention of 1899 (modified in 1954) obliges military forces not only to avoid destruction of enemy property, but to provide protection to it.[20] Theoretically, to prevent such looting, unclaimed property is moved to the custody of the Custodian of Enemy Property, to be handled until the return to its owner.

Examples of looting

By conquerors

- Following the death of Valentinian III in 455, the Vandals invaded and extensively looted the city of Rome.

- Mahmud of Ghazni repeatedly plundered the temple cities of Somnath, Mathura, Kannauj etc of India between 1000 A.D and 1027 A.D.

- After the siege of Constantinople in 1204, the crusaders looted the city and transferred its riches to Italy.

- Roman Catholic troops of Imperial Field Marschal Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly committed the Sack of Magdeburg in 1631. Magdeburg's civilian population was quickly reduced from 30,000 to 5,000, giving rise to a new term in German for annihilation by atrocities.

- In 1664 the Maratha leader Shivaji sacked and looted Surat.

- During World War II, both Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan engaged in massive and systematic looting of valuables worth tens of billions of dollars. See:

By others

- In 1977 the New York Blackout resulted in massive rioting and looting throughout the city of New York.

- In 1989 during Operation Just Cause, the invasion of Panama, there was massive systematic looting including office towers organized by the Dignity Battalions. Manuel Noriega is called the Father of modern looting.

- In 1992, during the Rodney King riots, widespread looting occurred in Los Angeles, California.

- After the United States occupied Iraq, the absence of Iraqi police and the reluctance of the U.S. to act as a police force enabled looters to raid homes and businesses, especially in Baghdad, most notably the Iraqi National Museum. During the looting, many hospitals were stripped of nearly all supplies. However, upon investigation many of the looting claims were in fact exaggerated. Most notably the Iraqi National Museum in which many curators had stored important artifacts in the vaults of Iraq's central bank.[23]

- In 2005 in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina there was extensive looting by some people desperate for food, with police being accused of joining in in some cases. Many were in search of food and water that were not available to them through any other means, as well as non-essential items such as beer and televisions.[24]

- In 2010 after the Haiti earthquake, slow distribution of the relief aid and the large number of affected people created concerns of civil unrest, marked by looting and mob justice against suspected looters.[25][26][27][28][29]

- During the 2011 London riots, gangs of youths undertook looting in a number of areas across the capital.[30] It has been suggested that rioting may have been organised [31] but it is unclear by whom, and to what end. London was last subjected to looting by gangs of youths who took advantage of war damage during the Second World War.[32] The 2011 London looting was copied on subsequent nights in other cities around England, including Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham.[33]

See also

References

- ^ "Baghdad protests over looting". BBC News. BBC. 2003-04-12. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

- ^ "World: Americas Looting frenzy in quake city". BBC Online Network. BBC. 1999-01-28. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

- ^ "Argentine president resigns". BBC News. BBC. 2001-12-21. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

- ^ "Definition of the word loot". Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com, LLC. 2010.

- ^ Hsi-sheng Chi, Warlord politics in China, 1916-1928, Stanford University Press, 1976, ISBN 0804708940, str. 93

- ^ Thinkexist.com, Genghis Khan quotes

- ^ John K. Thorton, African Background in American Colonization, in The Cambridge economic history of the United States, Stanley L. Engerman, Robert E. Gallman (ed.), Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0521394422, p.87. "African states waged war to acquire slaves [...] raids that appear to have been more concerned with obtaining loot (including slaves) than other objectives."

- ^ Sir John Bagot Glubb, The Empire of the Arabs, Hodder and Stoughton, 1963, p.283. "...thousand Christian captives formed part of the loot and were subsequently sold as slaves in the markets of Syria".

- ^ Template:Pl icon J. R. Kudelski, Tajemnice nazistowskiej grabieży polskich zbiorów sztuki, Warszawa 2004.

- ^ "Nazi loot claim 'compelling'". BBC News. October 2, 2002. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ Wayne H. Bowen, The History of Saudi Arabia, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008, ISBN 0313340129, Google Print, p.73

- ^ Template:Pl icon Andrzej Garlicki, Z dziejów Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej, Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 1986, ISBN 8302022454, p. 147

- ^ STEVEN LEE MYERS, Iraq Museum Reopens Six Years After Looting, New York Times, February 23, 2009

- ^ "Egypt's Antiquities Chief Combines Passion, Clout to Protect Artifacts". National Geographic News. October 24, 2006.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (January 13, 2002). "Elgin Marbles 'should be shared' with Greece". London: The Guardian UK. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ "MIĘDZY MODERNIZACJĄ A MARNOTRAWSTWEM" (in Polish). Institute of National Remembrance. Archived from the original on 2005-03-21. See also other copy online

- ^ "ARMIA CZERWONA NA DOLNYM ŚLĄSKU" (in Polish). Institute of National Remembrance. Archived from the original on 2005-03-21.

- ^ "Indonesian food minister tolerates looting". BBC News. July 21, 1998. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ E. Lauterpacht, C. J. Greenwood, Marc Weller, The Kuwait Crisis: Basic Documents, Cambridge University Press, 1991, ISBN 0521463084, geneva Convention&f=false Google Print, p.154

- ^ Barbara T. Hoffman, Art and cultural heritage: law, policy, and practice, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0521857643 Hague Convention&f=false Google Print, p.57

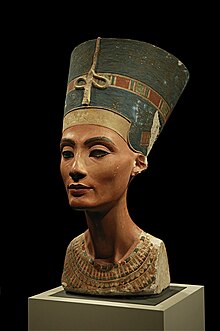

- ^ German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt (...) claimed to have an agreement with the Egyptian government that included rights to half his finds (...). But a new document suggests Borchardt intentionally misled Egyptian authorities about Nefertiti. Template:En icon "Top 10 Plundered Artifacts - Nefertiti's Bust". www.time.com. March 5, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-27.

- ^ Will Nefertiti Return to Egypt for a Brief Visit? Egypt Asks Germany for a Majestic Loan by Stan Parchin (June 17, 2006) about.com

- ^ Iraq's Endangered Cultural Heritage: An Update

- ^ Photos : Story in Pictures-- Hurricane Katrina : Aug 31, 2005: Looting in Mississippi

- ^ "Haiti street justice: The worst in people - 'We are at a moment of disaster,' man says after mob beats suspected looter"

- ^ "Looting Flares Where Authority Breaks Down"

- ^ "Anarchy looms on streets of Port-au-Prince - 3m survivors could run riot in Haiti unless aid gets in, UN warns"

- ^ "Looters roam Port-au-Prince as earthquake death toll estimate climbs - Hunger and thirst turn to violence in Haiti as planes unable to offload aid supplies fast enough"

- ^ Sherwell, Philip (16 January 2010). "Haiti earthquake: UN says worst disaster ever dealt with". London: Telegraph Co. uk. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Further riots in London as violence spreads across England". BBC News. August 9, 2011.

- ^ Lewis, Paul; Taylor, Matthew; Quinn, Ben (August 8, 2011). "Second night of violence in London – and this time it was organised". The Guardian. London.

- ^ http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/2WWcrime.htm

- ^ "UK riots: Trouble erupts in English cities". BBC News. August 10, 2011.

Sources

- Abudu, Margaret, et al., "Black Ghetto Violence: A Case Study Inquiry into the Spatial Pattern of Four Los Angeles Riot Event-Types," 44 Social Problems 483 (1997)

- Curvin, Robert and Bruce Porter, Blackout Looting (1979)

- Dynes, Russell & Enrico L. Quarantelli, "What Looting in Civil Disturbances Really Means," in Modern Criminals 177 (James F. Short, Jr. ed. 1970)

- Green, Stuart P., "Looting, Law, and Lawlessness," 81 Tulane Law Review 1129 (2007)

- Mac Ginty, "Looting in the Context of Violent Conflict: A Conceptualisation and Typology," 25 Third World Quarterly 857 (2004)