Autotransformer: Difference between revisions

Rv good-faith edit - Undid revision 488461030 by 182.156.153.49 (talk) |

|||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

A special form of autotransformer called a ''zig zag'' is used to provide grounding (earthing) on three-phase systems that otherwise have no connection to [[Earthing system|ground (earth)]]. A [[Zigzag transformer|zig-zag transformer]] provides a path for current that is common to all three phases (so-called ''zero sequence'' current). |

A special form of autotransformer called a ''zig zag'' is used to provide grounding (earthing) on three-phase systems that otherwise have no connection to [[Earthing system|ground (earth)]]. A [[Zigzag transformer|zig-zag transformer]] provides a path for current that is common to all three phases (so-called ''zero sequence'' current). |

||

POWER distribution in an auto transformer are also depand upone the no of similar turns in primary and secondary coil |

|||

===Audio=== |

===Audio=== |

||

Revision as of 03:04, 22 April 2012

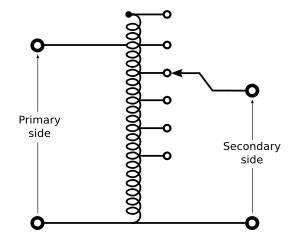

An autotransformer (sometimes called autostep down transformer)[1] is an electrical transformer with only one winding. The auto prefix refers to the single coil acting on itself rather than any automatic mechanism. In an autotransformer portions of the same winding act as both the primary and secondary. The winding has at least three taps where electrical connections are made. An autotransformer can be smaller, lighter and cheaper than a standard dual-winding transformer however the autotransformer does not provide electrical isolation.

Autotransformers are often used to step up or down between voltages in the 110-117-120 volt range and voltages in the 220-230-240 volt range, e.g., to output either 110 or 120V (with taps) from 230V input, allowing equipment from a 100 or 120V region to be used in a 230V region.

Operation

An autotransformer has a single winding with two end terminals, and one or more terminals at intermediate tap points. The primary voltage is applied across two of the terminals, and the secondary voltage taken from two terminals, almost always having one terminal in common with the primary voltage. The primary and secondary circuits therefore have a number of windings turns in common.[2] Since the volts-per-turn is the same in both windings, each develops a voltage in proportion to its number of turns. In an autotransformer part of the current flows directly from the input to the output, and only part is transferred inductively, allowing a smaller, lighter, cheaper core to be used as well as requiring only a single winding[3].

One end of the winding is usually connected in common to both the voltage source and the electrical load. The other end of the source and load are connected to taps along the winding. Different taps on the winding correspond to different voltages, measured from the common end. In a step-down transformer the source is usually connected across the entire winding while the load is connected by a tap across only a portion of the winding. In a step-up transformer, conversely, the load is attached across the full winding while the source is connected to a tap across a portion of the winding.

As in a two-winding transformer, the ratio of secondary to primary voltages is equal to the ratio of the number of turns of the winding they connect to. For example, connecting the load between the middle and bottom of the autotransformer will reduce the voltage by 50%. Depending on the application, that portion of the winding used solely in the higher-voltage (lower current) portion may be wound with wire of a smaller gauge, though the entire winding is directly connected.

Limitations

An autotransformer does not provide electrical isolation between its windings as an ordinary transfomer does; if the neutral side of the input is not at ground voltage, the neutral side of the output will not be either. A failure of the insulation of the windings of an autotransformer can result in full input voltage applied to the output. Also, a break in the part of the winding that is used as both primary and secondary will result in the transformer acting as an inductor in series with the load (which under light load conditions may result in near full input voltage being applied to the output). These are important safety considerations when deciding to use an autotransformer in a given application.

Because it requires both fewer windings and a smaller core, an autotransformer for power applications is typically lighter and less costly than a two-winding transformer, up to a voltage ratio of about 3:1; beyond that range, a two-winding transformer is usually more economical.

In three phase power transmission applications, autotransformers have the limitations of not suppressing harmonic currents and as acting as another source of ground fault currents. A large three-phase autotransformer may have a "buried" delta winding, not connected to the outside of the tank, to absorb some harmonic currents.

In practice, losses mean that both standard transformers and autotransformers are not perfectly reversible; one designed for stepping down a voltage will deliver slightly less voltage than required if used to step up. The difference is usually slight enough to allow reversal where the actual voltage level is not critical.

Like multiple-winding transformers, autotransformers operate on time-varying magnetic fields and so will not function with DC.

Applications

Power distribution

Autotransformers are frequently used in power applications to interconnect systems operating at different voltage classes, for example 138 kV to 66 kV for transmission. Another application is in industry to adapt machinery built (for example) for 480 V supplies to operate on a 600 V supply. They are also often used for providing conversions between the two common domestic mains voltage bands in the world (100-130 and 200-250). The links between the UK 400 kV and 275 kV 'Super Grid' networks are normally three phase autotransformers with taps at the common neutral end.

On long rural power distribution lines, special autotransformers with automatic tap-changing equipment are inserted as voltage regulators, so that customers at the far end of the line receive the same average voltage as those closer to the source. The variable ratio of the autotransformer compensates for the voltage drop along the line.

A special form of autotransformer called a zig zag is used to provide grounding (earthing) on three-phase systems that otherwise have no connection to ground (earth). A zig-zag transformer provides a path for current that is common to all three phases (so-called zero sequence current).

Audio

In audio applications, tapped autotransformers are used to adapt speakers to constant-voltage audio distribution systems, and for impedance matching such as between a low-impedance microphone and a high-impedance amplifier input.

Railways

In UK railway applications, it is common to power the trains at 25 kV AC. To increase the distance between electricity supply Grid feeder points they can be arranged to supply a 25-0-25 kV supply with the third wire (opposite phase) out of reach of the train's overhead collector pantograph. The 0 V point of the supply is connected to the rail while one 25 kV point is connected to the overhead contact wire. At frequent (about 10 km) intervals, an autotransformer links the contact wire to rail and to the second (antiphase) supply conductor. This system increases usable transmission distance, reduces induced interference into external equipment and reduces cost. A variant is occasionally seen where the supply conductor is at a different voltage to the contact wire with the autotransformer ratio modified to suit.[4]

Variable autotransformers

A variable autotransformer is made by exposing part of the winding coils and making the secondary connection through a sliding brush, giving a variable turns ratio.[5] Such a device is often referred to by the trademark name variac.

As with two-winding transformers, autotransformers may be equipped with many taps and automatic switchgear to allow them to act as automatic voltage regulators, to maintain a steady voltage at the customers' service during a wide range of load conditions. They can also be used to simulate low line conditions for testing. Another application is a lighting dimmer that doesn't produce the EMI typical of most thyristor dimmers.

By exposing part of the winding coils and making the secondary connection through a sliding brush, a continuously variable turns ratio can be obtained, allowing for very smooth control of voltage. Applicable only for relatively low voltage designs, this device is known as a variable AC transformer. The output voltage is not limited to the discrete voltages represented by actual number of turns. The voltage can be smoothly varied between turns as the brush has a relatively high resistance (compared with a metal contact) and the actual output voltage is a function of the relative area of brush in contact with adjacent windings.

From 1934 to 2002, Variac was a U.S. trademark of General Radio for a variable autotransformer intended to conveniently vary the output voltage for a steady AC input voltage. In 2004, Instrument Service Equipment applied for and obtained the Variac trademark for the same type of product.[citation needed]

See also

Notes

- ^ Paul Horowitz and Winfield Hill, The Art of Electronics Second Edition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge MA, 1989, ISBN 0-521-37095-7, page 58

- ^ Pansini. Electrical Transformers and Power Equipment. pp. 89–91.

- ^ Commercial site explaining why autotransformers are smaller

- ^ "Fahrleitungen electrischer Bahnen" BG Teubner-Verlag, Stuttgart, page 672. An English edition "Contact Lines for Electric Railways" appears to be out of print. This industry standard text describes the various European electrification principles. See the website of the UIC in Paris for the relevant international rail standards, in English. No comparable publications seem to exist for American railways, probably due to the paucity of electrified installations there.

- ^ Bakshi, M. V. and Bakshi, U. A. Electrical Machines - I. p. 330. ISBN 8184310099.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

- Terrell Croft and Wilford Summers (ed), American Electricians' Handbook, Eleventh Edition, McGraw Hill, New York (1987) ISBN 0-07013932-6

- Donald G. Fink and H. Wayne Beaty, Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers, Eleventh Edition,McGraw-Hill, New York, 1978, ISBN 0-07020974-X