Kevin Carter: Difference between revisions

m r2.7.3) (Robot: Adding ckb:کێڤین کارتەر |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

| birth_date = {{birth date|df=yes|1960|9|13}} |

| birth_date = {{birth date|df=yes|1960|9|13}} |

||

| birth_place = [[Johannesburg]], [[South Africa]] |

| birth_place = [[Johannesburg]], [[South Africa]] |

||

| death_date = {{death date and age|df=yes| |

| death_date = {{death date and age|df=yes|1995|7|27|1960|9|13}} |

||

| death_place = [[Johannesburg]], [[South Africa]] |

| death_place = [[Johannesburg]], [[South Africa]] |

||

| occupation = [[photojournalism|Photojournalist]] |

| occupation = [[photojournalism|Photojournalist]] |

||

Revision as of 14:46, 28 January 2013

Kevin Carter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 13 September 1960 |

| Died | 27 July 1995 (aged 34) |

| Occupation | Photojournalist |

Kevin Carter (13 September 1960 – 27 July 1994) was an award-winning South African photojournalist and member of the Bang-Bang Club. He was the recipient of a Pulitzer Prize for his photograph depicting the 1993 famine in Sudan. He committed suicide at the age of 33. His story is depicted in the 2010 feature film, The Bang-Bang-Club in which he was played by Taylor Kitsch.

Early life

Kevin Carter was born in apartheid South Africa and grew up in a middle-class, whites-only neighborhood. As a child, he occasionally saw police raids to arrest blacks who were illegally living in the area. He said later that he questioned how his parents, a Catholic, "liberal" family, could be what he described as 'lackadaisical' about fighting against apartheid.[1]

After high school, Carter dropped out of his studies to become a pharmacist and was drafted into the Army. To escape from the infantry he enlisted in the Air Force, which locked him into four years of service. In 1980, he witnessed a black mess-hall waiter being insulted. Carter defended the man, resulting in him being badly beaten by the other servicemen. He then went AWOL, attempted to start a new life as a radio disk-jockey named "David". This, however, proved more difficult than he had anticipated. Soon after, he decided to serve out the rest of his required military service. After witnessing the Church Street bombing in Pretoria in 1983, he decided to become a news photographer.[2]

Early work

Carter had started to work as weekend sports photographer in 1983. In 1984 he moved on to work for the Johannesburg Star, bent on exposing the brutality of apartheid.

Carter was the first to photograph a public execution "necklacing" by black Africans in South Africa in the mid-1980s. The victim was Maki Skosana, who had been accused of having a relationship with a police officer.[3] He later spoke of the images; "I was appalled at what they were doing. I was appalled at what I was doing. But then people started talking about those pictures... then I felt that maybe my actions hadn't been at all bad. Being a witness to something this horrible wasn't necessarily such a bad thing to do."[4]

Prize-winning photograph in Sudan

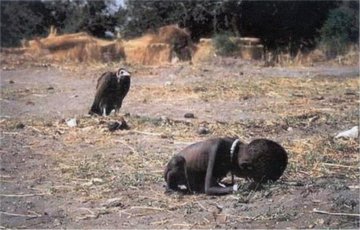

In March 1993, while on a trip to Sudan, Carter was preparing to photograph a starving toddler trying to reach a feeding center when a vulture landed nearby. Carter reported taking the picture, because it was his "job title", and leaving.[5] He came under criticism for failing to help the boy, Kong Nyong:

- The St. Petersburg Times in Florida said this of Carter: "The man adjusting his lens to take just the right frame of him suffering, might just as well be a predator, another vulture on the scene."[6]

Sold to the New York Times, the photograph first appeared on 26 March 1993 and was carried in many other newspapers around the world. Hundreds of people contacted the Times to ask the fate of the boy. The paper reported that it was unknown whether he had managed to reach the feeding center. In 1994, the photograph won the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography.[5]

Alternative account of the photograph

João Silva, a Portuguese photojournalist based in South Africa who accompanied Carter to Sudan, gave a different version of events in an interview with Japanese journalist and writer Akio Fujiwara that was published in Fujiwara's book The Boy who Became a Postcard (絵葉書にされた少年 - Ehagaki ni sareta shōnen).[7]

According to Silva, Carter and Silva travelled to Sudan with the United Nations aboard Operation Lifeline Sudan and landed in Southern Sudan on 11 March 1993. The UN told them that they would take off again in 30 minutes (the time necessary to distribute food), so they ran around looking to take shots. The UN started to distribute corn and the women of the village came out of their wooden huts to meet the plane. Silva went looking for guerrilla fighters, while Carter strayed no more than a few dozen feet from the plane.

Again according to Silva, Carter was quite shocked as it was the first time that he had seen a famine situation and so he took many shots of the children suffering from famine. Silva also started to take photos of children on the ground as if crying, which were not published. The parents of the children were busy taking food from the plane, so they had left their children only briefly while they collected the food. This was the situation for the boy in the photo taken by Carter. A vulture landed behind the boy.. To get the two in focus, Carter approached the scene very slowly so as not to scare the vulture away and took a photo from approximately 10 metres. He took a few more photos before chasing the bird away.

Two Spanish photographers who were in the same area at that time, José María Luis Arenzana and Luis Davilla, without knowing the photograph of Kevin Carter, took a picture in a similar situation. As recounted on several occasions, it was a feeding center, and the vultures came from a manure pit waste:

- "We took him and Pepe Arenzana to Ayod, where most of the time were in a feeding center where locals go. At one end of the enclosure, was a dump where waste and was pulling people to defecate. As these children are so weak and malnourished they are going ahead giving the impression that they are dead. As part of the fauna there are vultures that go for these remains. So if you grab a telephoto crush the child's perspective in the foreground and background and it seems that the vultures will eat it, but that's an absolute hoax, perhaps the animal is 20 meters."

Death

On 27 July 1994 Carter drove to the Braamfontein Spruit river, near the Field and Study Centre, an area where he used to play as a child, and took his own life by taping one end of a hose to his pickup truck’s exhaust pipe and running the other end to the passenger-side window. He died of carbon monoxide poisoning, aged 33. Portions of Carter's suicide note read:

- "I am depressed ... without phone ... money for rent ... money for child support ... money for debts ... money!!! ... I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings and corpses and anger and pain ... of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, of killer executioners ... I have gone to join Ken [recently deceased colleague Ken Oosterbroek] if I am that lucky."[8]

Cultural depictions

- A documentary entitled The Death of Kevin Carter: Casualty of the Bang Bang Club was nominated for an Academy Award in 2006.

- The Welsh band Manic Street Preachers recorded a song about him on their 1996 album Everything Must Go.

- There is a song 'Kevin Carter' on the 1996 album of Martin Simpson and Jessica Ruby Simpson, Band of Angels, which is a mainly factual, minimalist, and informative ballad.

- Poets and Madmen by heavy metal band Savatage is a loose concept-album based on a fictitious investigation of his legacy.

- Mark Danielewski's novel House of Leaves attributes a prize-winning photograph, based on that of Carter, to the novel's protagonist, Will Navidson. Within the confines of the novel, the starving Sudanese child is named Delial by Navidson. The story describes a photo similar to Carter's Pulitzer Prize-winning image, with footnotes directly referring to Carter and his suicide.

- Masha Hamilton's 2004 novel The Distance Between Us mentions Kevin Carter and is dedicated to "Kevin Carter and journalists everywhere who put their bodies and their souls on the line to cover war."

- Chilean born visual artist Alfredo Jaar presented the story of Kevin Carter and his Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph in the work The Sound of Silence, a cinematic video installation presented in his Politics of the Image exhibition at the South London Gallery in 2008. The narration goes on to tell about the life of the photograph after the death of its author.

- In 2010, he was played by Taylor Kitsch in the film The Bang-Bang-Club.

- The Canadian indie rock band Blinker the Star mentions Kevin Carter's death in their song "Still in Rome," from the 2003 album of the same name.

References

- ^ Marinovich and Silva (2000). pg 39.

- ^ Marinovich and Silva, 2000. 40-41

- ^ Marinovich and Silva, 2000. 38.

- ^ First draft by Tim Porter: Covering war in a free society

- ^ a b TIME Domestic (12 September 1994), Volume 144, No. 11, "The Life and Death of Kevin Carter" by Scott MacLeod, Johannesburg. Retrieved 19 February 2006.

- ^ The life and death of Kevin Carter: "Visiting Sudan, a little-known photographer took a picture that made the world weep. What happened afterward is a tragedy of another sort."

- ^ "The boy who became a postcard" (Ehagakini Sareta Shōnen). Akio Fujiwara 2005. ISBN 4-08-781338-X

- ^ MacLeod, Scott. "The Life and Death of Kevin Carter", Time magazine, 12 September 1994

- Marinovich, Greg (2000). The Bang-Bang Club Snapshots from a Hidden War. William Heinemann. ISBN 0-434-00733-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "The Death of Kevin Carter: Casualty of the Bang Bang Club" HBO documentary. 17 August 2006,

- "The boy who became a postcard" (Ehagakini Sareta Shōnen). Akio Fujiwara 2005. ISBN 4-08-781338-X

External links

- Use dmy dates from August 2012

- 1960 births

- 1994 deaths

- Anglo-African people

- The New York Times visual journalists

- People from Johannesburg

- Photographers who committed suicide

- South African photojournalists

- Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography winners

- War photographers

- South African Roman Catholics

- South African photographers

- Suicides by carbon monoxide poisoning

- Suicides in South Africa

- White South African people