Directed acyclic graph: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File: |

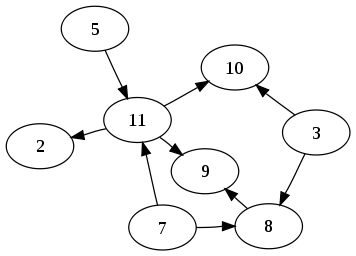

[[File:Directed acyclic graph 3.svg|right|frame|An example of a directed acyclic graph]] |

||

In [[mathematics]] and [[computer science]], a '''directed acyclic graph''' ('''DAG''' {{IPAc-en|audio=en-us-DAG.ogg|ˈ|d|æ|g}}), is a [[directed graph]] with no [[Cycle_graph#Directed_cycle_graph|directed cycles]]. That is, it is formed by a collection of [[Vertex (graph theory)|vertices]] and [[edge (graph theory)|directed edges]], each edge connecting one vertex to another, such that there is no way to start at some vertex ''v'' and follow a sequence of edges that eventually loops back to ''v'' again.<ref>{{citation|title=Graph theory: an algorithmic approach|first=Nicos|last=Christofides|publisher=Academic Press|year=1975|pages=170–174}}.</ref><ref>{{citation|title=Graphs: Theory and Algorithms|first1=K.|last1=Thulasiraman|first2=M. N. S.|last2=Swamy|publisher=John Wiley and Son|year=1992|isbn=978-0-471-51356-8|contribution=5.7 Acyclic Directed Graphs|page=118}}.</ref><ref>{{citation|title=Digraphs: Theory, Algorithms and Applications|first=Jørgen|last=Bang-Jensen|series=Springer Monographs in Mathematics|edition=2nd|publisher=Springer-Verlag|year=2008|isbn=978-1-84800-997-4|contribution=2.1 Acyclic Digraphs|pages=32–34}}.</ref> |

In [[mathematics]] and [[computer science]], a '''directed acyclic graph''' ('''DAG''' {{IPAc-en|audio=en-us-DAG.ogg|ˈ|d|æ|g}}), is a [[directed graph]] with no [[Cycle_graph#Directed_cycle_graph|directed cycles]]. That is, it is formed by a collection of [[Vertex (graph theory)|vertices]] and [[edge (graph theory)|directed edges]], each edge connecting one vertex to another, such that there is no way to start at some vertex ''v'' and follow a sequence of edges that eventually loops back to ''v'' again.<ref>{{citation|title=Graph theory: an algorithmic approach|first=Nicos|last=Christofides|publisher=Academic Press|year=1975|pages=170–174}}.</ref><ref>{{citation|title=Graphs: Theory and Algorithms|first1=K.|last1=Thulasiraman|first2=M. N. S.|last2=Swamy|publisher=John Wiley and Son|year=1992|isbn=978-0-471-51356-8|contribution=5.7 Acyclic Directed Graphs|page=118}}.</ref><ref>{{citation|title=Digraphs: Theory, Algorithms and Applications|first=Jørgen|last=Bang-Jensen|series=Springer Monographs in Mathematics|edition=2nd|publisher=Springer-Verlag|year=2008|isbn=978-1-84800-997-4|contribution=2.1 Acyclic Digraphs|pages=32–34}}.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 01:09, 6 April 2014

In mathematics and computer science, a directed acyclic graph (DAG /ˈdæɡ/ ), is a directed graph with no directed cycles. That is, it is formed by a collection of vertices and directed edges, each edge connecting one vertex to another, such that there is no way to start at some vertex v and follow a sequence of edges that eventually loops back to v again.[1][2][3]

DAGs may be used to model many different kinds of information. A collection of tasks that must be ordered into a sequence, subject to constraints that certain tasks must be performed earlier than others, may be represented as a DAG with a vertex for each task and an edge for each constraint; algorithms for topological ordering may be used to generate a valid sequence. DAGs may also be used to model processes in which data flows in a consistent direction through a network of processors. The reachability relation in a DAG forms a partial order, and any finite partial order may be represented by a DAG using reachability. Additionally, DAGs may be used as a space-efficient representation of a collection of sequences with overlapping subsequences.

The corresponding concept for undirected graphs is a forest, an undirected graph without cycles. Choosing an orientation for a forest produces a special kind of directed acyclic graph called a polytree. However there are many other kinds of directed acyclic graph that are not formed by orienting the edges of an undirected acyclic graph, and every undirected graph has an acyclic orientation, an assignment of a direction for its edges that makes it into a directed acyclic graph. For this reason it may be more accurate to call directed acyclic graphs acyclic directed graphs or acyclic digraphs.

Partial orders and topological ordering

Each directed acyclic graph gives rise to a partial order ≤ on its vertices, where u ≤ v exactly when there exists a directed path from u to v in the DAG. However, many different DAGs may give rise to this same reachability relation: for example, the DAG with two edges a → b and b → c has the same reachability as the graph with three edges a → b, b → c, and a → c. If G is a DAG, its transitive reduction is the graph with the fewest edges that represents the same reachability as G, and its transitive closure is the graph with the most edges that represents the same reachability.

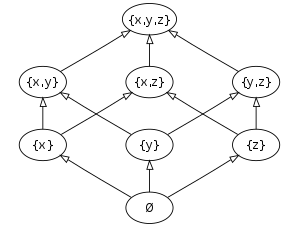

The transitive closure of G has an edge u → v for every related pair u ≤ v of distinct elements in the reachability relation of G, and may therefore be thought of as a direct translation of the reachability relation ≤ into graph-theoretic terms: every partially ordered set may be translated into a DAG in this way. If a DAG G represents a partial order ≤, then the transitive reduction of G is a subgraph of G with an edge u → v for every pair in the covering relation of ≤; transitive reductions are useful in visualizing the partial orders they represent, because they have fewer edges than other graphs representing the same orders and therefore lead to simpler graph drawings. A Hasse diagram of a partial order is a drawing of the transitive reduction in which the orientation of each edge is shown by placing the starting vertex of the edge in a lower position than its ending vertex.

Every directed acyclic graph has a topological ordering, an ordering of the vertices such that the starting endpoint of every edge occurs earlier in the ordering than the ending endpoint of the edge. In general, this ordering is not unique; a DAG has a unique topological ordering if and only if it has a directed path containing all the vertices, in which case the ordering is the same as the order in which the vertices appear in the path. The family of topological orderings of a DAG is the same as the family of linear extensions of the reachability relation for the DAG, so any two graphs representing the same partial order have the same set of topological orders. Topological sorting is the algorithmic problem of finding topological orderings; it can be solved in linear time. It is also possible to check whether a given directed graph is a DAG in linear time, by attempting to find a topological ordering and then testing whether the resulting ordering is valid.

Some algorithms become simpler when used on DAGs instead of general graphs, based on the principle of topological ordering. For example, it is possible to find shortest paths and longest paths from a given starting vertex in DAGs in linear time by processing the vertices in a topological order, and calculating the path length for each vertex to be the minimum or maximum length obtained via any of its incoming edges. In contrast, for arbitrary graphs the shortest path may require slower algorithms such as Dijkstra's algorithm or the Bellman–Ford algorithm, and longest paths in arbitrary graphs are NP-hard to find.

DAG representations of partial orderings have many applications in scheduling problems for systems of tasks with ordering constraints. For instance, a DAG may be used to describe the dependencies between cells of a spreadsheet: if one cell is computed by a formula involving the value of a second cell, draw a DAG edge from the second cell to the first one. If the input values to the spreadsheet change, all of the remaining values of the spreadsheet may be recomputed with a single evaluation per cell, by topologically ordering the cells and re-evaluating each cell in this order. Similar problems of task ordering arise in makefiles for program compilation, instruction scheduling for low-level computer program optimization, and PERT scheduling for management of large human projects. Dependency graphs without circular dependencies form directed acyclic graphs.

Data processing networks

A directed graph may be used to represent a network of processing elements; in this formulation, data enters a processing element through its incoming edges and leaves the element through its outgoing edges. Examples of this include the following:

- In electronic circuit design, a combinational logic circuit is an acyclic system of logic gates that computes a function of an input, where the input and output of the function are represented as individual bits.

- Dataflow programming languages describe systems of values that are related to each other by a directed acyclic graph. When one value changes, its successors are recalculated; each value is evaluated as a function of its predecessors in the DAG.

- In compilers, straight line code (that is, sequences of statements without loops or conditional branches) may be represented by a DAG describing the inputs and outputs of each of the arithmetic operations performed within the code; this representation allows the compiler to perform common subexpression elimination efficiently.

- In most spreadsheet systems, the dependency graph that connects one cell to another if the first cell stores a formula that uses the value in the second cell must be a directed acyclic graph. Cycles of dependencies are disallowed because they cause the cells involved in the cycle to not have a well-defined value. Additionally, requiring the dependencies to be acyclic allows a topological order to be used to schedule the recalculations of cell values when the spreadsheet is changed.

Causal and temporal structures

Graphs that have vertices representing events, and edges representing causal relations between events, are often acyclic – arranging the vertices in linear order of time, all arrows point in the same direction as time, from parent to child (due to causality affecting the future, not the past), and thus have no loops.

For instance, a Bayesian network represents a system of probabilistic events as nodes in a directed acyclic graph, in which the likelihood of an event may be calculated from the likelihoods of its predecessors in the DAG. In this context, the moral graph of a DAG is the undirected graph created by adding an (undirected) edge between all parents of the same node (sometimes called marrying), and then replacing all directed edges by undirected edges.

Another type of graph with a similar causal structure is an influence diagram, the nodes of which represent either decisions to be made or unknown information, and the edges of which represent causal influences from one node to another. In epidemiology, for instance, these diagrams are often used to estimate the expected value of different choices for intervention.

Family trees may also be seen as directed acyclic graphs, with a vertex for each family member and an edge for each parent-child relationship. Despite the name, these graphs are not necessarily trees – the graphs of matrilineal descent ("mother" relationships between women) and patrilineal descent ("father" relationships between men) are trees however – because of the possibility of marriages between distant relatives (so a child has a common ancestor on both the mother's and father's side). However, the time ordering of births (a parent's birthday is always prior to their child's birthday) causes these graphs to be acyclic. For the same reason, the version history of a distributed revision control system generally has the structure of a directed acyclic graph, in which there is a vertex for each revision and an edge connecting pairs of revisions that were directly derived from each other; these are not trees in general due to merges.

Paths with shared structure

A third type of application of directed acyclic graphs arises in representing a set of sequences as paths in a graph. For example, the directed acyclic word graph is a data structure in computer science formed by a directed acyclic graph with a single source and with edges labeled by letters or symbols; the paths from the source to the sinks in this graph represent a set of strings, such as English words. Any set of sequences can be represented as paths in a tree, by forming a tree node for every prefix of a sequence and making the parent of one of these nodes represent the sequence with one fewer element; the tree formed in this way for a set of strings is called a trie. A directed acyclic word graph saves space over a trie by allowing paths to diverge and rejoin, so that a set of words with the same possible suffixes can be represented by a single tree node.

The same idea of using a DAG to represent a family of paths occurs in the binary decision diagram,[4][5] a DAG-based data structure for representing binary functions. In a binary decision diagram, each non-sink vertex is labeled by the name of a binary variable, and each sink and each edge is labeled by a 0 or 1. The function value for any truth assignment to the variables is the value at the sink found by following a path, starting from the single source vertex, that at each non-sink vertex follows the outgoing edge labeled with the value of that vertex's variable. Just as directed acyclic word graphs can be viewed as a compressed form of tries, binary decision diagrams can be viewed as compressed forms of decision trees that save space by allowing paths to rejoin when they agree on the results of all remaining decisions.

In many randomized algorithms in computational geometry, the algorithm maintains a history DAG representing features of some geometric construction that have been replaced by later finer-scale features; point location queries may be answered, as for the above two data structures, by following paths in this DAG.

Relation to other kinds of graphs

A polytree is a directed graph formed by orienting the edges of a free tree. Every polytree is a DAG. In particular, this is true of the arborescences formed by directing all edges outwards from the root of a tree. A multitree (also called a strongly ambiguous graph or a mangrove) is a directed graph in which there is at most one directed path (in either direction) between any two nodes; equivalently, it is a DAG in which, for every node v, the set of nodes reachable from v forms a tree.

Any undirected graph may be made into a DAG by choosing a total order for its vertices and orienting every edge from the earlier endpoint in the order to the later endpoint. However, different total orders may lead to the same acyclic orientation. The number of acyclic orientations is equal to |χ(−1)|, where χ is the chromatic polynomial of the given graph.[6]

Any directed graph may be made into a DAG by removing a feedback vertex set or a feedback arc set. However, the smallest such set is NP-hard to find. An arbitrary directed graph may also be transformed into a DAG, called its condensation, by contracting each of its strongly connected components into a single supervertex.[7] When the graph is already acyclic, its smallest feedback vertex sets and feedback arc sets are empty, and its condensation is the graph itself.

Enumeration

The graph enumeration problem of counting directed acyclic graphs was studied by Robinson (1973).[8] The number of DAGs on n labeled nodes, for n = 0, 1, 2, 3, ..., is

These numbers may be computed by the recurrence relation

Eric W. Weisstein conjectured,[9] and McKay et al. (2004) proved,[10] that the same numbers count the (0,1) matrices in which all eigenvalues are positive real numbers. The proof is bijective: a matrix A is an adjacency matrix of a DAG if and only if A + I is a (0,1) matrix with all eigenvalues positive, where I denotes the identity matrix. Note that a DAG adjacency matrix must have a zero diagonal, otherwise one or more vertices have arcs to themselves.

References

- ^ Christofides, Nicos (1975), Graph theory: an algorithmic approach, Academic Press, pp. 170–174.

- ^ Thulasiraman, K.; Swamy, M. N. S. (1992), "5.7 Acyclic Directed Graphs", Graphs: Theory and Algorithms, John Wiley and Son, p. 118, ISBN 978-0-471-51356-8.

- ^ Bang-Jensen, Jørgen (2008), "2.1 Acyclic Digraphs", Digraphs: Theory, Algorithms and Applications, Springer Monographs in Mathematics (2nd ed.), Springer-Verlag, pp. 32–34, ISBN 978-1-84800-997-4.

- ^ Lee, C. Y. (1959), "Representation of switching circuits by binary-decision programs", Bell Systems Technical Journal, 38: 985–999.

- ^ Akers, Sheldon B. (1978), "Binary decision diagrams", IEEE Transactions on Computers, C-27 (6): 509–516, doi:10.1109/TC.1978.1675141.

- ^ Stanley, Richard P. (1973), "Acyclic orientations of graphs", Discrete Mathematics, 5 (2): 171–178, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(73)90108-8.

- ^ Harary, Frank; Norman, Robert Z.; Cartwright, Dorwin (1965), Structural Models: An Introduction to the Theory of Directed Graphs, John Wiley & Sons, p. 63.

- ^ a b Robinson, R. W. (1973), "Counting labeled acyclic digraphs", in Harary, F. (ed.), New Directions in the Theory of Graphs, Academic Press, pp. 239–273. See also Harary, Frank; Palmer, Edgar M. (1973), Graphical Enumeration, Academic Press, p. 19, ISBN 0-12-324245-2.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Weisstein's Conjecture". MathWorld.

- ^ McKay, B. D.; Royle, G. F.; Wanless, I. M.; Oggier, F. E.; Sloane, N. J. A.; Wilf, H. (2004), "Acyclic digraphs and eigenvalues of (0,1)-matrices", Journal of Integer Sequences, 7, Article 04.3.3.