Porphyria: Difference between revisions

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

[[Seizures]] often accompany this disease. Most seizure medications exacerbate this condition. Treatment can be problematic: [[barbiturates]] must be avoided. Some benzodiazepines are safe, and, when used in conjuction with newer anti-seizure medications such as gabapentin offer a possible regime for seizure control. |

[[Seizures]] often accompany this disease. Most seizure medications exacerbate this condition. Treatment can be problematic: [[barbiturates]] must be avoided. Some benzodiazepines are safe, and, when used in conjuction with newer anti-seizure medications such as gabapentin offer a possible regime for seizure control. |

||

==Culture and history== |

|||

===Historical patients=== |

|||

Modern medicine has suggested that the insanity exhibited by [[George III of the United Kingdom|King George III]] was the result of porphyria. Research has shown that porphyria is another hereditary disease plaguing the British royal family (besides [[hemophilia]]), apparently from the line of the monarchs of Scotland. Research has shown that both [[James I of England|James VI & I]] and [[Mary I of Scotland]] probably suffered from the disease. Queen [[Anne of Great Britain]], Queen Victoria's granddaughter [[Charlotte, Duchess of Saxe-Meiningen|Charlotte]] (a sister of Wilhelm II), and [[Prince William of Gloucester]] were also sufferers. |

|||

New research indicates that [[Vincent van Gogh]] may have suffered from acute intermittent porphyria (Loftus & Arnold 1991). Erik Vachon, the little-known builder whose character was combined with that of [[Svengali]] to create ''[[The Phantom of the Opera]]'' probably suffered from erythropoietic porphyria. |

|||

It has also been suggested that [[Nebuchadnezzar II|King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon]] suffered from some form of Porphyria (cf. Daniel 4, see Beveridge 2003). |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 21:06, 3 July 2006

| Porphyria | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

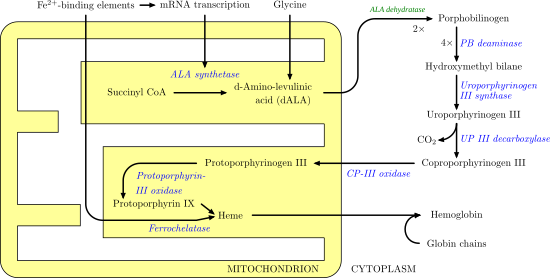

The porphyrias are inherited or acquired disorders of certain enzymes in the heme biosynthetic pathway (also called porphyrin pathway). They are broadly classified as hepatic porphyrias or erythropoietic porphyrias, based on the site of the overproduction and mainly accumulation of the porphyrins (or their chemical precursors).

Overview

In humans, porphyrins are the main precursors of heme, an essential constituent of hemoglobin, myoglobin, and cytochrome.

Deficiency in the enzymes of the porphyrin pathway leads to insufficient production of heme. This is, however, not the main problem; most enzymes—even when less functional—have enough residual activity to assist in heme biosynthesis. The largest problem in these deficiencies is the accumulation of porphyrins, the heme precursors, which are toxic to tissue in high concentrations. The chemical properties of these intermediates determine in which tissue they accumulate, whether they are photosensitive, and how the compound is excreted (in the urine or feces).

Subtypes

There are eight enzymes in the heme biosynthetic pathway: the first and the last three are in the mitochondria, while the other four are in the cytosol. Defects in any of these can lead to some form of porphyria.

- δ-aminolevulinate (ALA) synthase

- δ-aminolevulinate (ALA) dehydratase

- hydroxymethylbilane (HMB) synthase (also called PBG deaminase)

- uroporphyrinogen (URO) synthase

- uroporphyrinogen (URO) decarboxylase

- coproporphyrinogen (COPRO) oxidase

- protoporphyrinogen (PROTO) oxidase

- ferrochelatase

Hepatic porphyrias

The hepatic porphyrias include:

- Doss porphyria: ALA dehydratase deficiency

- acute intermittent porphyria (AIP): a deficiency in HMB synthase

- hereditary coproporphyria (HCP): a deficiency in COPRO oxidase

- variegate porphyria (VP): a deficiency in PROTO oxidase

- porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT): a deficiency in URO decarboxylase

Erythropoietic porphyria

The erythropoietic porphyrias include:

- X-linked sideroblastic anemia (XLSA): a deficiency in ALA synthase

- congenital erythropoietic porphyria (CEP): a deficiency in URO synthase

- erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP): a deficiency in ferrochelatase

Porphyria variegata

Variegate porphyria (also porphyria variegata or mixed porphyria) results from a partial deficiency in PROTO oxidase, manifesting itself with skin lesions similar to those of porphyria cutanea tarda combined with acute neurologic attacks.

Signs and symptoms

The hepatic porphyrias primarily affect the nervous system, resulting in abdominal pain, vomiting, acute neuropathy, seizures, and mental disturbances, including hallucinations, depression, anxiety, and paranoia. Cardiac arrhythmias and tachycardia (fast heart rate) may develop as the autonomic nervous system is affected. Pain can be severe and can, in some cases, be both acute and chronic in nature. Constipation is frequently present, as the nervous system of the gut is affected.

The erythropoietic porphyrias primarily affect the skin, causing photosensitivity (photodermatitis), blisters, necrosis of the skin and gums, itching, and swelling, and increased hair growth on areas such as the forehead.

In some forms of porphyria, accumulated heme precursors excreted in the urine may change its color, after exposure to sunlight, to a dark reddish or dark brown color. Even a purple hue may be seen. Heme precursors may also accumulate in the teeth and fingernails, giving them a reddish appearance.

Attacks of the disease can be triggered by drugs (e.g., barbiturates, alcohol, sulfa drugs, oral contraceptives, sedatives, and certain antibiotics), other chemicals, certain foods, and exposure to the sun. Fasting can also trigger attacks.

Treatment

Acute porphyria

A high-carbohydrate diet is typically recommended; in severe attacks, a glucose 10% infusion is commenced, which may aid in recovery. If drugs have caused the attack, discontinuing the offending substances is essential. Infection is one of the top causes of attacks and requires vigorous treatment. Pain is extremely severe and almost always requires the use of opiates to reduce it to tolerable levels. Pain should be treated early as medically possible due to its severity. Nausea can be severe; it may respond to phenothiazine drugs but is sometimes intractable. Hot water baths/showers may lessen nausea temporarily, though caution should be used to avoid burns or falls.

Hematin and haem arginate are the drugs of choice in acute porphyria, in the United States and the United Kingdom, respectively. These drugs need to be given very early in an attack to be effective. Effectiveness varies amongst individuals. They are not curative drugs but can shorten attacks and reduce the intensity of an attack. Side effects are rare but can be serious. These heme-like substances theoretically inhibit ALA synthase and hence the accumulation of toxic precursors. In the United Kingdom, supplies of this drug are maintained at two national centers. In the United States, one company manufactures Panhematin for infusion. The American Porphyria Foundation has information regarding the quick procurement of the drug.

Patients with a history of acute porphyria are recommended to wear an alert bracelet or other identification at all times in case they develop severe symptoms: a result of which may be they cannot explain to healthcare professionals about their condition and the fact that some drugs are absolutely contraindicated.

Patients who experience frequent attacks can develop chronic neuropathic pain in extremities as well as chronic pain in the gut.This is thought to be due to axonal nerve deterioration in affected areas of the nervous system. In these cases treatment with long-acting opioids may be indicated. Some cases of chronic pain can be difficult to manage and may require treatment using multiple modalities. Depression often accompanies the disease and is best dealt with by treating the offending symptoms and if needed the judicious use of anti-depressants.

Seizures often accompany this disease. Most seizure medications exacerbate this condition. Treatment can be problematic: barbiturates must be avoided. Some benzodiazepines are safe, and, when used in conjuction with newer anti-seizure medications such as gabapentin offer a possible regime for seizure control.

References

- Adams C. Did vampires suffer from the disease porphyria--or not? The Straight Dope 7 May 1999 Article

- Anderson KE, Bloomer JR, Bonkovsky HL, Kushner JP, Pierach CA, Pimstone NR, Desnick RJ. Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of the acute porphyrias. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:439-50. PMID 15767622.

- Beveridge A. The madness of politics. J R Soc Med 2003;96:602-4. PMID 14645615.

- Kauppinen R. Porphyrias. Lancet 2005;365:241-52. PMID 15652607.

- Loftus LS, Arnold WN. Vincent van Gogh's illness: acute intermittent porphyria? BMJ 1991;303:1589-91. PMID 1773180.

- Thadani H, Deacon A, Peters T. Diagnosis and management of porphyria. BMJ 2000;320:1647-51. Fulltext. PMID 10856069.