Dying-and-rising god: Difference between revisions

why would you say "pages 53-54" when the thing you cite is actually on p. 143? |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

==Scholarly criticism== |

==Scholarly criticism== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

The category "dying-and-rising-god" was debated throughout the 20th century, most modern scholars questioning its ubiquity in the world's mythologies.<ref name=Garry>''Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature'' by Jane Garry (Dec 1, 2004) ISBN 0765612607 pages 19-20</ref> |

The category "dying-and-rising-god" was debated throughout the 20th century, most modern scholars questioning its ubiquity in the world's mythologies.<ref name=Garry>''Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature'' by Jane Garry (Dec 1, 2004) ISBN 0765612607 pages 19-20</ref> |

||

<ref name= |

<ref name=Eddy143/> |

||

By the end of the 20th century the overall scholarly consensus had emerged against the category is of limited applicability outside of [[Ancient Near Eastern religions]] and derived traditions.<ref name=Garry/> |

By the end of the 20th century the overall scholarly consensus had emerged against the category is of limited applicability outside of [[Ancient Near Eastern religions]] and derived traditions.<ref name=Garry/> |

||

[[Tryggve Mettinger]] (who supports the category) states that there is a scholarly consensus that the category is inappropriate from a historical perspective.<ref name=Met7221>Mettinger, Tryggve N. D. (2001). ''The Riddle of Resurrection: Dying and Rising Gods in the Ancient Near East''. Almqvist & Wiksell, pages 7 and 221</ref> |

[[Tryggve Mettinger]] (who supports the category) states that there is a scholarly consensus that the category is inappropriate from a historical perspective.<ref name=Met7221>Mettinger, Tryggve N. D. (2001). ''The Riddle of Resurrection: Dying and Rising Gods in the Ancient Near East''. Almqvist & Wiksell, pages 7 and 221</ref> |

||

[[Kurt Rudolph]] in 1986 argued that the oft-made connection between the |

[[Kurt Rudolph]] in 1986 argued that the oft-made connection between the mystery religions and the idea of dying and rising divinities is defective. Against this view, Mettinger (2001) affirms that many of the gods of the mystery religions do indeed die, descend to the underworld, are lamented and retrieved by a woman and restored to life.<ref name="Gary19f"/> |

||

While the concept of a "dying-and-rising god" has a longer history, it was significantly advocated by Frazer's ''Golden Bough'' (1906–1914). At first received very favourably, the idea was attacked by [[Roland de Vaux]] in 1933, and was the subject of controversial debate over the following decades.<ref name="Mettinger2004">Tryggve Mettinger, "The 'Dying and Rising God': A survey of Research from Frazer to the Present Day", in Batto et al. (eds.), ''David and Zion: Biblical Studies in Honor of J.J.M. Roberts'' (2004), [https://books.google.ch/books?id=Vlkb0cSBGlIC&pg=PA373 373–386]</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

One of the leading scholars in the deconstruction of Frazer's "dying-and-rising god" category was [[Jonathan Z. Smith]], whose 1969 dissertation discusses Frazer's ''Golden Bough'',<ref>Jonathan Zittell Smith ''The Glory, Jest and Riddle. James George Frazer and The Golden Bough'', Yale dissertation (1969).[http://rel.as.ua.edu/pdf/rel490jzsdiss.pdf]</ref> and who in [[Mirco Eliade]]'s 1987 ''Encyclopedia of religion'' wrote the "Dying and rising gods" entry, where he dismisses the category as "largely a misnomer based on imaginative reconstructions and exceeding late or highly ambiguous texts", suggesting a more detailed categorisation into "dying gods" and "disappearing gods", arguing that before Christianity, the two categories were distinct and gods who "died" did not return, and those who returned never truly "died".<ref name=JZSmith>Smith, Jonathan Z. (1987). "Dying and Rising Gods," in ''The Encyclopedia of Religion'' Vol. IV, edited by Mircea Eliad ISBN 0029097002 Macmillan, pages 521-527</ref> |

|||

The overall scholarly consensus is that while the examples provided often involve death of the deity, they do not generally involve resurrection of the same deity.<ref name=Garry/> Eddy and Boyd state that upon careful analysis, it turns out that there is often either no death, no resurrection or no god in the examples used to construct each of the examples in the category.<ref name=Eddy53>''The Jesus legend: a case for the historical reliability of the synoptic gospels'' by Paul R. Eddy, Gregory A. Boyd 2007 ISBN 0-8010-3114-1 [https://books.google.ch/books?id=WgROZMp4zDMC&lpg=PA1&pg=PA143#v=onepage&q&f=false p. 143] |

|||

Smith gave a more detailed account of his views specifically on the question of parallels to Christianity in ''Drudgery Divine'' (1990).<ref> Jonathan Z. Smith "On Comparing Stories", ''Drudgery Divine: On the Comparison of Early Christianities and the Religions of Late Antiquity'' (1990), [https://books.google.ch/books?id=cTGuREaQOewC&pg=PA85#v=onepage&q&f=false 85–115]. |

|||

</ref> [[Jonathan Z. Smith]], a scholar of comparative religions, writes the category is "largely a misnomer based on imaginative reconstructions and exceedingly late or highly ambiguous texts."<ref name=Bailey/><ref name=JZSmith>Smith, Jonathan Z. (1987). "Dying and Rising Gods," in ''The Encyclopedia of Religion'' Vol. IV, edited by Mircea Eliad ISBN 0029097002 Macmillan, pages 521-527</ref> The ''Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion'' states that Smith is correct in pointing out many discontinuities within the category, and although some scholars support the category, it is generally seen as involving excessive generalization.<ref name=Bailey>Lee W. Bailey, "Dying and rising gods" in: David A. Leeming, Kathryn Madden and Stanton Marlan (eds.) ''Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion'' (2009) ISBN 038771801X Springer, pages 266-267</ref> [[Gerald O'Collins]] states that surface-level application of analogous symbolism is a case of [[parallelomania]] which exaggerate the importance of trifling resemblances, long abandoned by mainstream scholars.<ref name=Collins>[[Gerald O'Collins]], "The Hidden Story of Jesus" ''New Blackfriars'' Volume 89, Issue 1024, pages 710–714, November 2008</ref> |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Smith's 1987 article was widely-received, and during the 1990s, scholarly consensus seemed to shift towards his rejection of the concept as overly simplified, although it continued to be invoked by scholars writing about Ancient Near Eastern mythology.<ref>Mettinger (2004) cites M.S. Smith, ''The Ugaritic Baal Cycle'' and H.-P. Müller, "Sterbende ud auferstehende Vegetationsgötter? Eine Skizze," TZ 53 (1997:374)</ref> |

|||

As of 2009, the ''Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion'' summarizes the current scholarly consensus as ambiguous, with some scholars rejecting Frazer's "broad universalist category" preferring to emphasize the differences between the various traditions, while others continue to view the category as applicable.<ref name=Bailey>Lee W. Bailey, "Dying and rising gods" in: David A. Leeming, Kathryn Madden and Stanton Marlan (eds.) ''Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion'' (2009) ISBN 038771801X Springer, pages 266-267</ref> |

|||

[[Gerald O'Collins]] states that surface-level application of analogous symbolism is a case of [[parallelomania]] which exaggerate the importance of trifling resemblances, long abandoned by mainstream scholars.<ref name=Collins>[[Gerald O'Collins]], "The Hidden Story of Jesus" ''New Blackfriars'' Volume 89, Issue 1024, pages 710–714, November 2008</ref> |

|||

Beginning with an overview of the [[Classical Athens|Athenian]] ritual of growing and withering herb gardens at the [[Adonis (mythology)|Adonis]] festival, in his book ''The Gardens of Adonis'' [[Marcel Detienne]] suggests that rather than being a stand-in for crops in general (and therefore the cycle of death and rebirth), these herbs (and Adonis) were part of a complex of associations in the Greek mind that centered on spices.<ref name=GardenAdonis>''The Gardens of Adonis'' by Marcel Detienne, Janet Lloyd and Jean-Pierre Vernant (Apr 4, 1994) ISBN 0691001049 Princeton pages iv-xi</ref> These associations included seduction, trickery, gourmandizing, and the anxieties of childbirth.<ref name=Batto/> From his point of view, Adonis's death is only one datum among the many that must be used to analyze the festival, the myth, and the god.<ref name=Elinor301>''Comparative Criticism'' Volume 1 by Elinor Shaffer (Nov 1, 1979) ISBN 0521222966 page 301</ref><ref name=Batto>''David and Zion'', Biblical Studies in Honor of J.J.M. Roberts, edited by Bernard Frank Batto, Kathryn L. Roberts and J. J. M. Roberts (Jul 2004) ISBN 1575060922 pages 381-383</ref> |

|||

A main criticism charges the group of analogies with [[reductionism]], insofar as it subsumes a range of disparate myths under a single category and ignores important distinctions. [[Marcel Detienne]] argues that it risks making Christianity the standard by which all religion is judged, since death and resurrection are more central to Christianity than many other faiths.<ref>{{harvnb|Detienne|1994}}; see also {{harvnb|Burkert|1987}}</ref> [[Dag Øistein Endsjø]], a scholar of religion, points out how a number of those often defined as dying-and-rising-deities, like [[Jesus]] and a number of figures in [[Resurrection#Ancient_Greek_religion|ancient Greek religion]], actually died as ordinary mortals, only to become gods of various stature after they were resurrected from the dead. Not dying as gods, they thus defy the definition of “dying-and-rising-gods”.<ref>Dag Øistein Endsjø. ''Greek Resurrection Beliefs and the Success of Christianity.'' New York: Palgrave Macmillan 2009.</ref> |

A main criticism charges the group of analogies with [[reductionism]], insofar as it subsumes a range of disparate myths under a single category and ignores important distinctions. [[Marcel Detienne]] argues that it risks making Christianity the standard by which all religion is judged, since death and resurrection are more central to Christianity than many other faiths.<ref>{{harvnb|Detienne|1994}}; see also {{harvnb|Burkert|1987}}</ref> [[Dag Øistein Endsjø]], a scholar of religion, points out how a number of those often defined as dying-and-rising-deities, like [[Jesus]] and a number of figures in [[Resurrection#Ancient_Greek_religion|ancient Greek religion]], actually died as ordinary mortals, only to become gods of various stature after they were resurrected from the dead. Not dying as gods, they thus defy the definition of “dying-and-rising-gods”.<ref>Dag Øistein Endsjø. ''Greek Resurrection Beliefs and the Success of Christianity.'' New York: Palgrave Macmillan 2009.</ref> |

||

Since the 1990s, Smith's scholarly rejection of the category has been widely embraced by [[Christian apologists]] wishing to defend the [[historicity of Jesus]], while scholarly defenses of the concept (or its applicability to mystery religion) have been embraced by the "[[new atheism]]" movement wishing to argue the "[[Christ myth theory]]".<ref> |

|||

Albert McIlhenny, ''This Is the Sun?: Zeitgeist and Religion'', Labarum Publishing (2011), chapter 14, "Dying and Rising Gods", 189–213. |

|||

Itself published with a Christian apologist publisher, and mostly focussing on the naive "Christ solar myth" meme propagated by the 2007 film ''[[Zeitgeist (film series)|Zeitgeist]]'', McIlhenny (2011) criticizes the agenda-driven selective reception of scholarship on both sides, in Christian apologetics (embracing Smith) and popular atheism (embracing Mettinger). |

|||

</ref> |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 09:16, 25 April 2015

| Dying-and-rising god | |

|---|---|

The Return of Persephone by Frederic Leighton (1891). | |

| Description | A dying-and-rising god is born, suffers a death-like experience, and is subsequently reborn. |

| Proponents | James Frazer, Carl Jung, Tryggve Mettinger |

| Subject | Mythology |

A dying god, or departure of the gods[1][2][3][4] is a motif in mythology where a god or an entire pantheon dies or is killed or destroyed.

A dying-and-rising death-rebirth, or resurrection deity is a a related motif where the god dies and is also resurrected.[5][6][7][8] "Death or departure of the gods" is motif A192 in Stith Thompson's Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, while "resurrection of gods" is motif A193.[9]

Frequently cited examples of dying gods are Balder in Norse mythology, Quetzalcoatl in Aztec mythology. A special subcategory is the death of an entire pantheon, the most notable example being Ragnarok in Norse mythology, with other examples from Ireland, India, Hawaii and Tahiti.[9]

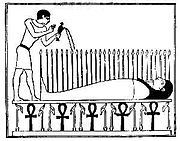

Examples of gods who die and later return to life are most often cited from the religions of the Ancient Near East, and traditions influenced by them including Biblical and Greco-Roman mythology and by extension Christianity. The concept of dying-and-rising god was first proposed in comparative mythology by James Frazer's seminal The Golden Bough. Frazer associated the motif with fertility rites surrounding the yearly cycle of vegetation. Frazer cited the examples of Osiris, Tammuz, Adonis and Attis, Dionysus and Jesus Christ.[10]

Frazer's interpretation of the category has been critically discussed in 20th-century scholarship,[11] to the conclusion that many examples from the world's mythologies included under "dying and rising" should only be considered "dying" but not "rising", and that the genuine dying-and-rising god is a characteristic feature of Ancient Near Eastern mythologies and the derived mystery cults of Late Antiquity.[12]

Overview

The motif of a dying deity appears within the mythology of diverse cultures – perhaps because attributes of deities were derived from everyday experiences, and the ensuing conflicts often included death.[13] [14][15] These examples range from Baldr in Norse mythology to the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl in Aztec mythology to the Japanese Izanami.[14][16][17]

The methods of death vary, e.g., in the myth of Baldr (whose account was likely first written down the 12th century), he is inadvertently killed by his blind brother Höðr who is tricked into shooting a mistletoe-tipped arrow at him, and his body is then set aflame on a ship as it sails out to sea.[14][16] Baldr does not come back to life because not all living creatures shed tears for him, and his death then leads to the "doom of the gods".[14][16]

In contrast, in most variations of his story, Quetzalcoatl (whose story dates to around the first century) is tricked by Tezcatlipoca to over-drink and then burns himself to death out of remorse for his own shameful deeds.[14][18] Quetzalcoatl does not resurrect and come back to life as himself, but some versions of his story have a flock of birds flying away from his ashes, and in some variants, Quetzalcoatl sails away on the ocean never to return.[14][18]

Hawaiian deities can die and depart the world in a number of ways; e.g., some gods who were killed on Lanai by Lanikuala departed for the skies.[14] In contrast, Kaili leaves the world by a canoe which is never seen again.[14] The Japanese god Izanami, on the other hand, dies of a fever and Izanagi goes to Yomi, the land of gloom, to retrieve her, but she has already changed to a deteriorated state and Izanagi will not bring her back, and she pursues Izanagi, but he manages to escape.[14][17]

Some gods who die are also seen as either returning or bring about life in some other form, often associated with the vegetation cycle, or a staple food, in effect taking the form of a vegetation deity.[14][15] Examples include Ishtar and Persephone, who die every year.[13] The yearly death of Ishtar when she goes underground represents the lack of growth, while her return the rebirth of the farming cycle.[13] Most scholars hold that although the gods suggested in this motif die, they do not generally return in terms of rising as the same deity, although scholars such as Mettinger contend that in some cases they do.[14][19]

Development of the concept

The term "dying god" is associated with the works of James Frazer,[8] Jane Ellen Harrison, and their fellow Cambridge Ritualists.[20] At the end of the 19th century, in their The Golden Bough[8] and Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, Frazer and Harrison argued that all myths are echoes of rituals, and that all rituals have as their primordial purpose the manipulation of natural phenomena.[8]

Early in the 20th century, Gerald Massey argued that there are similarities between the Egyptian dying-and-rising god myths and Jesus.[21] However, Massey's historical errors often render his works nonsensical, e.g., Massey stated that the biblical references to Herod the Great were based on the myth of "Herrut" the evil hydra serpent, while the existence of Herod the Great can be well established without reliance on Christian sources.[22] Stanley Porter has specifically rejected the works of Massey and his followers.[23]

The Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung argued that archetypal processes such as death and resurrection were part of the "trans-personal symbolism" of the collective unconscious, and could be utilized in the task of psychological integration.[24][page needed] He also proposed that the myths of the pagan gods who symbolically died and resurrected foreshadowed Christ's literal/physical death and resurrection.[24][page needed] The overall view of Carl Jung regarding religious themes and stories is that they are expressions of events occurring in the unconscious of the individuals - regardless of their historicity.[25] From the symbolic perspective, Jung sees dying and rising gods as an archetypal process resonating with the collective unconscious through which the rising god becomes the greater personality in the Jungian self.[13] In Jung's view, a biblical story such as the resurrection of Jesus (which he saw as a case of dying and rising) may be true or not, but that has no relevance to the psychological analysis of the process, and its impact.[25]

The analysis of Osiris permeates the later religious psychology of Carl Jung more than any other element.[26] In 1950 Jung wrote that those who partake in the Osiris myth festival and follow the ritual of his death and the scattering of his body to restart the vegetation cycle as a rebirth "experience the permanence and continuity of life which outlasts all changes of form".[27] Jung wrote that Osiris provided the key example of the rebirth process in that initially only the Pharaohs "had an Osiris" but later other Egyptians nobles acquired it and eventually it led in the concept of soul for all individuals in Christianity.[28] Jung believed that Christianity itself derived its significance from the archetypal relationship between Osiris and Horus versus God the Father and Jesus, his son.[26] However, Jung also postulated that the rebirth applied to Osiris (the father), and not Horus, the son.[26]

The general applicability of the death and resurrection of Osiris to the dying-and-rising-god analogy has been criticized, on the grounds that it derived from the harvesting rituals that related the rising and receding waters of the Nile river and the farming cycle.[23][29][30] The cutting down of barley and wheat was related to the death of Osiris, while the sprouting of shoots was thought to be based on the power of Osiris to resurrect the farmland.[23][29][31] In general rebirth analogies based on the vegetation cycle are viewed as the weakest elements in the death-rebirth analogies.[13]

In Greek mythology Dionysus, the son of Zeus was a horned child who was torn to pieces by Titans who lured him with toys, then boiled and ate him.[32][33] Zeus then destroyed the Titans by thunderbolt as a result of their action against Dionysus and from the ashes humans were formed.[33] However, Dionysus' grandmother Rhea managed to put some of his pieces back together (principally from his heart that was spared) and brought him back to life.[32][33] Scholars such as Barry Powell have suggested Dionysus as an example of resurrection.[34]

Myth theorist Robert M. Price has also stated that the Jesus narrative has strong parallels with other Middle Eastern narratives about life-death-rebirth deities, parallels that he writes Christian apologists have tried to minimize.[35] Price's view has virtually no support in the secular scholarly community.[36]

Scholarly criticism

The category "dying-and-rising-god" was debated throughout the 20th century, most modern scholars questioning its ubiquity in the world's mythologies.[14] [37] By the end of the 20th century the overall scholarly consensus had emerged against the category is of limited applicability outside of Ancient Near Eastern religions and derived traditions.[14] Tryggve Mettinger (who supports the category) states that there is a scholarly consensus that the category is inappropriate from a historical perspective.[19] Kurt Rudolph in 1986 argued that the oft-made connection between the mystery religions and the idea of dying and rising divinities is defective. Against this view, Mettinger (2001) affirms that many of the gods of the mystery religions do indeed die, descend to the underworld, are lamented and retrieved by a woman and restored to life.[12]

While the concept of a "dying-and-rising god" has a longer history, it was significantly advocated by Frazer's Golden Bough (1906–1914). At first received very favourably, the idea was attacked by Roland de Vaux in 1933, and was the subject of controversial debate over the following decades.[38] One of the leading scholars in the deconstruction of Frazer's "dying-and-rising god" category was Jonathan Z. Smith, whose 1969 dissertation discusses Frazer's Golden Bough,[39] and who in Mirco Eliade's 1987 Encyclopedia of religion wrote the "Dying and rising gods" entry, where he dismisses the category as "largely a misnomer based on imaginative reconstructions and exceeding late or highly ambiguous texts", suggesting a more detailed categorisation into "dying gods" and "disappearing gods", arguing that before Christianity, the two categories were distinct and gods who "died" did not return, and those who returned never truly "died".[40] Smith gave a more detailed account of his views specifically on the question of parallels to Christianity in Drudgery Divine (1990).[41] Smith's 1987 article was widely-received, and during the 1990s, scholarly consensus seemed to shift towards his rejection of the concept as overly simplified, although it continued to be invoked by scholars writing about Ancient Near Eastern mythology.[42] As of 2009, the Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion summarizes the current scholarly consensus as ambiguous, with some scholars rejecting Frazer's "broad universalist category" preferring to emphasize the differences between the various traditions, while others continue to view the category as applicable.[13] Gerald O'Collins states that surface-level application of analogous symbolism is a case of parallelomania which exaggerate the importance of trifling resemblances, long abandoned by mainstream scholars.[43]

Beginning with an overview of the Athenian ritual of growing and withering herb gardens at the Adonis festival, in his book The Gardens of Adonis Marcel Detienne suggests that rather than being a stand-in for crops in general (and therefore the cycle of death and rebirth), these herbs (and Adonis) were part of a complex of associations in the Greek mind that centered on spices.[44] These associations included seduction, trickery, gourmandizing, and the anxieties of childbirth.[45] From his point of view, Adonis's death is only one datum among the many that must be used to analyze the festival, the myth, and the god.[46][45]

A main criticism charges the group of analogies with reductionism, insofar as it subsumes a range of disparate myths under a single category and ignores important distinctions. Marcel Detienne argues that it risks making Christianity the standard by which all religion is judged, since death and resurrection are more central to Christianity than many other faiths.[47] Dag Øistein Endsjø, a scholar of religion, points out how a number of those often defined as dying-and-rising-deities, like Jesus and a number of figures in ancient Greek religion, actually died as ordinary mortals, only to become gods of various stature after they were resurrected from the dead. Not dying as gods, they thus defy the definition of “dying-and-rising-gods”.[48]

Since the 1990s, Smith's scholarly rejection of the category has been widely embraced by Christian apologists wishing to defend the historicity of Jesus, while scholarly defenses of the concept (or its applicability to mystery religion) have been embraced by the "new atheism" movement wishing to argue the "Christ myth theory".[49]

See also

- Comparative mythology

- Mother goddess

- Mytheme

- Ouroboros

- Pandeism

- Resurrection

- Psychology of religion

- Vegetation deity

Notes

- ^ Leeming, "Dying god"

- ^ Burkert 1979, 99

- ^ Stookey 2004, 99

- ^ Miles 2009, 193

- ^ Leeming, "Dying god" (2004)

- ^ Burkert 1979, 99

- ^ Stookey 2004, 99

- ^ a b c d Miles 2009, 193

- ^ a b Thompson's categories A192 and A193, with subcategories:

A192. Death or departure of the gods.

- A192.1. Death of the gods. Icel.: MacCulloch Eddic 340ff. (at the Doom); Irish myth: Cross; India: Thompson-Balys; Hawaii: Beckwith Myth 110; Tahiti: Henry 231; Chinese: Werner 99, Eberhard FFC CXX 141; Africa: Bouveignes 12.

- A192.1.1. Old god slain by young god. Irish myth: Cross.

- A192.1.2. God killed and eaten. Easter Is.: Métraux Ethnology 311.

- A192.2. Departure of gods. Tonga: Gifford 102, Nukuhiva (Marquesas): Handy 123.

- A192.2.1. Deity departs for heaven (skies). Polynesia: Moriori (Chatham Is.), Pora Pora (Society Is.), Samoa: Beckwith Myth 38, 43, *241ff., 254; So. Am. Indian (Apapocuvá-Guarani): Métraux RMLP XXXIII 122.

- A192.2.1.1. Deity departs for moon. Polynesia: Hawaii, Beckwith Myth 220, *241; Tuamotu: Stimson MS (T-G. 3/931).

- A192.2.2. Divinity departs in boat over sea. Hawaii: Beckwith Myth 29, *37.

- A192.2.3. Divinity departs to submarine home. Hawaii: Beckwith Myth 206.

- A192.2.4. Divinity departs in column of flame. Pora Pora (Society Is.): Beckwith Myth 38.

- A192.2.1. Deity departs for heaven (skies). Polynesia: Moriori (Chatham Is.), Pora Pora (Society Is.), Samoa: Beckwith Myth 38, 43, *241ff., 254; So. Am. Indian (Apapocuvá-Guarani): Métraux RMLP XXXIII 122.

- A192.3. Expected return of deity. Banks Is. (Fiji): Beckwith Myth 316.

- A192.4. Divinity becomes mortal. Tonga: Beckwith Myth 75.

- ^ Frazer, quoted in Mettinger 2001:18, cited after Garry and El-Shamy, p. 19

- ^ summary in Mettinger (2001:15–39)

- ^ a b Garry and El-Shamy (2004:19f.), citing Mettinger (2001:217f.): "The world of ancient Near Eastern religions actually knew a number of deities that may be properly described as dying and rising [... although o]ne should not hypostasize these gods into a specific type ' the dying and rising god.'"

- ^ a b c d e f Lee W. Bailey, "Dying and rising gods" in: David A. Leeming, Kathryn Madden and Stanton Marlan (eds.) Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion (2009) ISBN 038771801X Springer, pages 266-267

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature; a handbook by Jane Garry and Hasan M El-Shamy (Dec 1, 2004) ISBN 0765612607 pages 19-20 Cite error: The named reference "Garry" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Thematic Guide to World Mythology by Lorena Laura Stookey (Mar 30, 2004) ISBN 0313315051 pages 106-107

- ^ a b c Norse Mythology: A Guide to Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs by John Lindow (Oct 17, 2002) ISBN 0195153820 pages 66-68

- ^ a b Handbook of Japanese Mythology by Michael Ashkenazi (Nov 5, 2003) ISBN 1576074676 page 174

- ^ a b The Myth of Quetzalcoatl by Enrique Florescano and Lysa Hochroth (Oct 29, 2002) ISBN 0801871018 page 42

- ^ a b Mettinger, Tryggve N. D. (2001). The Riddle of Resurrection: Dying and Rising Gods in the Ancient Near East. Almqvist & Wiksell, pages 7 and 221

- ^ Ackerman 2002, 163, lists divine kingship, taboo, and the dying god as "key concepts" of not only Frazer, but Harrison and others of the ritualist school, in contrast to differences among these scholars.

- ^ Massey, Gerald (1907). Ancient Egypt, the light of the world. London: T. Fisher Unwin. pp. 728–914. ISBN 978-1-4588-1251-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Unmasking the Pagan Christ by Stanley E. Porter and Stephen J. Bedard 2006 ISBN 1894667719 page 18

- ^ a b c Unmasking the Pagan Christ by Stanley E. Porter and Stephen J. Bedard 2006 ISBN 1894667719 page 24

- ^ a b Crowley, Vivianne (2000). Jung: A Journey of Transformation:Exploring His Life and Experiencing His Ideas. Wheaton Illinois: Quest Books. ISBN 978-0-8356-0782-7.

- ^ a b Care for the Soul: Exploring the Intersection of Psychology and Theology by Mark R. McMinn and Timothy R. Phillips (Apr 25, 2001) ISBN 0830815538 Intervarsity page 287

- ^ a b c Alane Sauder-MacGuire, "Osiris and the Egyptian Religion" in the Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion by David A. Leeming, Kathryn Madden and Stanton Marlan (Nov 6, 2009) ISBN 038771801X Springer, pages 651-653

- ^ The Archetypes and The Collective Unconscious (Collected Works of C.G. Jung Vol.9 Part 1) by C. G. Jung and R.F.C. Hull (Aug 1, 1981) ISBN 0691018332 page 117

- ^ The Archetypes and The Collective Unconscious (Collected Works of C.G. Jung Vol.9 Part 1) by C. G. Jung and R.F.C. Hull (Aug 1, 1981) ISBN 0691018332 page 128

- ^ a b Egyptian Mythology, a Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt by Geraldine Pinch 2004 ISBN 0195170245 Oxford Univ Press page 91

- ^ New Testament tools and studies", Bruce Manning Metzger, p. 19, Brill Archive, 1960

- ^ Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt by Margaret Bunson 1999 ISBN 0517203804 page 290

- ^ a b Euripides and Alcestis by Kiki Gounaridou (Sep 3, 1998) University Press Of America ISBN 0761812318 page 71

- ^ a b c The Greek World by Anton Powell (Sep 28, 1997) ISBN 0415170427 page 494

- ^ A Short Introduction to Classical Myth by Barry B. Powell (Jan 2002) ISBN 0130258393 pages 105–107

- ^ Price, Robert M. "Jesus at the Vanishing Point" in James K. Beilby & Paul Rhodes Eddy (eds.) The Historical Jesus: Five Views. InterVarsity, 2009, p. 75.

- ^ Bart Ehrman 2012. Did Jesus Exist? Oxford University Press.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Eddy143was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Tryggve Mettinger, "The 'Dying and Rising God': A survey of Research from Frazer to the Present Day", in Batto et al. (eds.), David and Zion: Biblical Studies in Honor of J.J.M. Roberts (2004), 373–386

- ^ Jonathan Zittell Smith The Glory, Jest and Riddle. James George Frazer and The Golden Bough, Yale dissertation (1969).[1]

- ^ Smith, Jonathan Z. (1987). "Dying and Rising Gods," in The Encyclopedia of Religion Vol. IV, edited by Mircea Eliad ISBN 0029097002 Macmillan, pages 521-527

- ^ Jonathan Z. Smith "On Comparing Stories", Drudgery Divine: On the Comparison of Early Christianities and the Religions of Late Antiquity (1990), 85–115.

- ^ Mettinger (2004) cites M.S. Smith, The Ugaritic Baal Cycle and H.-P. Müller, "Sterbende ud auferstehende Vegetationsgötter? Eine Skizze," TZ 53 (1997:374)

- ^ Gerald O'Collins, "The Hidden Story of Jesus" New Blackfriars Volume 89, Issue 1024, pages 710–714, November 2008

- ^ The Gardens of Adonis by Marcel Detienne, Janet Lloyd and Jean-Pierre Vernant (Apr 4, 1994) ISBN 0691001049 Princeton pages iv-xi

- ^ a b David and Zion, Biblical Studies in Honor of J.J.M. Roberts, edited by Bernard Frank Batto, Kathryn L. Roberts and J. J. M. Roberts (Jul 2004) ISBN 1575060922 pages 381-383

- ^ Comparative Criticism Volume 1 by Elinor Shaffer (Nov 1, 1979) ISBN 0521222966 page 301

- ^ Detienne 1994; see also Burkert 1987

- ^ Dag Øistein Endsjø. Greek Resurrection Beliefs and the Success of Christianity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan 2009.

- ^ Albert McIlhenny, This Is the Sun?: Zeitgeist and Religion, Labarum Publishing (2011), chapter 14, "Dying and Rising Gods", 189–213. Itself published with a Christian apologist publisher, and mostly focussing on the naive "Christ solar myth" meme propagated by the 2007 film Zeitgeist, McIlhenny (2011) criticizes the agenda-driven selective reception of scholarship on both sides, in Christian apologetics (embracing Smith) and popular atheism (embracing Mettinger).

References

- Ackerman, Robert (2002). The Myth and Ritual School: J.G. Frazer and the Cambridge Ritualists. New York: Routledge.

- Burkert, Walter

- 1979. Structure and History in Greek Mythology and Ritual. London: University of California Press.

- 1987. Ancient Mystery Cults. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP. ISBN 0-674-03386-8

- Cumont, Franz (1911). The Oriental Religions in Roman Paganism. Chicago: Open Court.

- Cumont, Franz (1903). The Mysteries of Mithra. London: Kegan Paul.

- Detienne, Marcel. 1994. The Gardens of Adonis: Spices in Greek Mythology. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton UP. ISBN 0-391-00611-8

- Endsjø, Dag Øistein 2009. Greek Resurrection Beliefs and the Success of Christianity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-61729-2

- Frazer, James George (1890). The Golden Bough. New York: Touchstone, 1996.. ISBN 0-684-82630-5

- Gaster, Theodor, H. 1950. Thespis: Ritual, Myth, and Drama in the Ancient Near East. New York: Henry Schuman. ISBN 0-87752-188-3

- Godwin, Joscelyn. 1994. The Theosophical Enlightenment. Albany: State U of New York P. ISBN 0-7914-2151-1

- Jensen, Adolf (1963). Myth and Cult among Primitive Peoples. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-39823-4

- Leeming, David. "Dying god". The Oxford Companion to World mythology. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. UC - Irvine. 5 June 2011 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t208.e469>

- Lewis, C. S. (1970). "Myth Become Fact." God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics. Ed. Walter Hooper. Reprint ed. Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans, 1994. ISBN 0-8028-0868-9

- Mettinger, Tryggve N. D. (2001). The Riddle of Resurrection: Dying and Rising Gods in the Ancient Near East. Coniectanea Biblica, Old Testament, 50, Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, ISBN 978-91-22-01945-9

- Miles, Geoffrey. 2009. Classical Mythology in English Literature: A Critical Anthology. Taylor & Francis e-Library.

- Nash, Ronald H. 2003. The Gospel and the Greeks: Did the New Testament Borrow from Pagan Thought?. Phillipsburg, N.J.: P&R. ISBN 0-87552-559-8

- Price, Robert M. "Jesus at the Vanishing Point" in James K. Beilby & Paul Rhodes Eddy (eds.) The Historical Jesus: Five Views. InterVarsity, 2009

- Smith, Jonathan Z. (1987). "Dying and Rising Gods." In The Encyclopedia of Religion: Vol. 3.. Ed. Mircea Eliade. New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan.

- Stookey, Lorena Laura. 2004. Thematic Guide to World Mythology. Westport: Greenwood.