Globe: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

A '''globe''' is a three-[[dimension]]al scale [[Physical model|model]] of [[Earth]] ('''terrestrial globe''' or '''geographical globe''') or other celestial body such as a planet or moon. While models can be made of objects with arbitrary or irregular shapes, the term ''globe'' is used only for models of objects that are approximately spherical. The word “globe” comes from the [[Latin]] word ''globus'', meaning round mass or [[sphere]]. Some terrestrial globes include relief to show mountains and other features on the Earth’s surface. |

A '''globe''' is a three-[[dimension]]al scale [[Physical model|model]] of [[Earth]] ('''terrestrial globe''' or '''geographical globe''') or other celestial body such as a planet or moon. While models can be made of objects with arbitrary or irregular shapes, the term ''globe'' is used only for models of objects that are approximately spherical. The word “globe” comes from the [[Latin]] word ''globus'', meaning round mass or [[sphere]]. Some terrestrial globes include relief to show mountains and other features on the Earth’s surface. |

||

There are also globes, called '''celestial globes''' or '''astronomical globes''', which are spherical representations of the [[celestial sphere]], showing the apparent positions of the [[star]]s and [[constellation]]s in the [[sky]]. |

There are also globes, called '''celestial globes''' or '''astronomical globes''', which are spherical representations of the [[celestial sphere]], showing the apparent positions of the [[star]]s and [[constellation]]s in the [[sky]]. A globe is just an approximate model of the Earth and is not drawn to scale.<ref>More about Globe</ref> |

||

==Terrestrial and planetary== |

==Terrestrial and planetary== |

||

Revision as of 12:37, 29 August 2015

A globe is a three-dimensional scale model of Earth (terrestrial globe or geographical globe) or other celestial body such as a planet or moon. While models can be made of objects with arbitrary or irregular shapes, the term globe is used only for models of objects that are approximately spherical. The word “globe” comes from the Latin word globus, meaning round mass or sphere. Some terrestrial globes include relief to show mountains and other features on the Earth’s surface.

There are also globes, called celestial globes or astronomical globes, which are spherical representations of the celestial sphere, showing the apparent positions of the stars and constellations in the sky. A globe is just an approximate model of the Earth and is not drawn to scale.[1]

Terrestrial and planetary

A globe is the only representation of the earth that does not distort either the shape or the size of large features; flat maps are created using a map projection that inevitably introduces an increasing amount of distortion the larger the area that the map shows. A typical scale for a terrestrial globe is roughly 1:40 million. This corresponds to a globe with a circumference of one metre, since the circumference of the real Earth is almost exactly 40 million metres.[2][3]

Sometimes a globe has surface texture showing topography; in these, elevations are exaggerated, otherwise they would be hardly visible. Most modern globes are also imprinted with parallels and meridians, so that one can tell the approximate coordinates of a specific place. Globes may also show the boundaries of countries and their names, a feature that can quickly become out of date, as countries change their name or borders.

Celestial

Celestial globes show the apparent positions of the stars in the sky. They omit the Sun, Moon and planets because the positions of these bodies vary relative to those of the stars, but the ecliptic, along which the Sun moves, is indicated.

A potential issue arises regarding the “handedness” of celestial globes. If the globe is constructed so that the stars are in the positions they actually occupy on the imaginary celestial sphere, then the star field will appear back-to-front on the surface of the globe (all the constellations will appear as their mirror images). This is because the view from Earth, positioned at the centre of the celestial sphere, is of the inside of the celestial sphere, whereas the celestial globe is viewed from the outside. For this reason, celestial globes may be produced in mirror image, so that at least the constellations appear the “right way round”. Some modern celestial globes address this problem by making the surface of the globe transparent. The stars can then be placed in their proper positions and viewed through the globe, so that the view is of the inside of the celestial sphere, as it is from Earth.

History

The sphericity of the Earth was established by Greek astronomy in the 3rd century BC, and the earliest terrestrial globe appeared from that period. The earliest known example is the one constructed by Crates of Mallus in Cilicia (now Çukurova in modern-day Turkey), in the mid-2nd century BC.

No terrestrial globes from Antiquity or the Middle Ages have survived. An example of a surviving celestial globe is part of a Hellenistic sculpture, called the Farnese Atlas, surviving in a 2nd-century AD Roman copy in the Naples Archaeological Museum, Italy.[6]

Early terrestrial globes depicting the entirety of the Old World were constructed in the Islamic world.[7][8] According to David Woodward, one such example was the terrestrial globe introduced to Beijing by the Persian astronomer, Jamal ad-Din, in 1267.[9]

The earliest extant terrestrial globe was made in 1492 by Martin Behaim (1459–1537) with help from the painter Georg Glockendon.[6] Behaim was a German mapmaker, navigator, and merchant. Working in Nuremberg, Germany, he called his globe the "Nürnberg Terrestrial Globe." It is now known as the Erdapfel. Before constructing the globe, Behaim had traveled extensively. He sojourned in Lisbon from 1480, developing commercial interests and mingling with explorers and scientists. In 1485–1486, he sailed with Portuguese explorer Diogo Cão to the coast of West Africa. He began to construct his globe after his return to Nürnberg in 1490.

Another early globe, the Hunt-Lenox Globe, ca. 1510, is thought to be the source of the phrase Hic Sunt Dracones, or “Here be dragons”. A similar grapefruit-sized globe made from two halves of an ostrich egg was found in 2012 and is believed to date from 1504. It may be the oldest globe to show the New World. Stefaan Missine, who analyzed the globe for the Washington Map Society journal Portolan, said it was “part of an important European collection for decades.”[10] After a year of research in which he consulted many experts, Missine concluded the Hunt-Lenox Globe was a copper cast of the egg globe.[10]

A facsimile globe showing America was made by Martin Waldseemueller in 1507. Another “remarkably modern-looking” terrestrial globe of the Earth was constructed by Taqi al-Din at the Istanbul observatory of Taqi al-Din during the 1570s.[11]

The world’s first seamless celestial globe was built by Mughal scientists under the patronage of Jahangir.

Globus IMP, electro-mechanical devices including five-inch globes have been used in Soviet and Russian spacecraft from 1961 to 2002 as navigation instruments. In 2001, the TMA version of the Soyuz spacecraft replaced this instrument with a virtual globe.[12]

In the 1800s small pocket globes (less than 3 inches) were status symbols for gentlemen and educational toys for rich children.[13]

Manufacture

Traditionally, globes were manufactured by gluing a printed paper map onto a sphere, often made from wood.

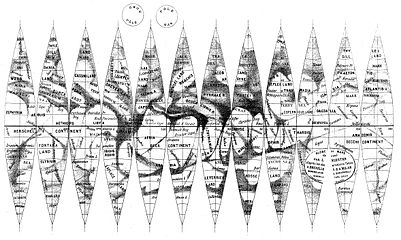

The most common type has long, thin gores (strips) of paper that narrow to a point at the poles,[14] small disks cover over the inevitable irregularities at these points. The more gores there are, the less stretching and crumpling is required to make the paper map fit the sphere. From a geometric point of view, all points on a sphere are equivalent – one could select any arbitrary point on the Earth, and create a paper map that covers the Earth with strips that come together at that point and the antipodal point.

Modern globes are often made from thermoplastic. Flat, plastic disks are printed with a distorted map of one of the Earth's Hemispheres. This is placed in a machine which molds the disk into a hemispherical shape. The hemisphere is united with its opposite counterpart to form a complete globe.

A globe is usually mounted at a 23.5° angle on a meridian. In addition to making it easy to use this mounting also represents the angle of the planet in relation to its sun and the spin of the planet. This makes it easy to visualize how days and seasons change.

Notable examples

- The Unisphere in Queens, New York, at 120 feet (36.6 m) in diameter, is the world’s largest geographical globe. (There are larger spherical structures, such as the Cinesphere in Toronto, Canada, but this does not have geographical or astronomical markings.)

- Eartha, currently the world’s largest rotating globe (41 ft or 12 m in diameter), at the DeLorme headquarters in Yarmouth, Maine

- The Mapparium, three-story, stained glass globe at the Mary Baker Eddy Library in Boston, which visitors walk through via a 30-foot (9.1 m) glass bridge.

- The Babson globe in Wellesley, Massachusetts, a 26-foot-diameter (7.9 m) globe which originally rotated on its axis and on its base to simulate day and night and the seasons

- The giant globe in the lobby of The News Building in New York City.

- The Hitler Globe, also known as the Führer globe, was formally named the Columbus Globe for State and Industry Leaders. Two editions existed during Hitler’s lifetime, created during the mid-1930s on his orders. (The second edition changed the name of Abyssinia to Italian East Africa). These globes were “enormous” and very costly. According to the New York Times, “the real Columbus globe was nearly the size of a Volkswagen and, at the time, more expensive.” Several still exist, including three in Berlin: one at a geographical institute, one at the Märkisches Museum, and another at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. The latter has a Soviet bullet hole through Germany. One of the two in public collections in Munich has an American bullet hole through Germany. There are several in private hands inside and out of Germany. A much smaller version of Hitler’s globe was mocked by Charlie Chaplin in The Great Dictator, a film released in 1940.[15]

Gallery

-

19th Century projections of the terrestrial globe, from the UBC Library Digital Collections

-

Martin Behaim with his Erdapfel

-

Top view of 1765 de l'Isle globe

-

The Unisphere, attributed to "uribe"/Uri Baruchin

-

1594, Mechanised Celestial Globe

-

A Globus IMP navigation instrument from a Voskhod spacecraft.

-

Eartha, the largest rotating globe in the world.

-

A map of Mars that circulated commercially in the 19th century. It is an example of how maps are printed in order to be folded around a sphere to form a globe.

-

Multitouch spherical Globe with digital EARTH based on multitouch software

See also

- Analemma

- Armillary sphere

- Cartography

- Dymaxion map

- Emery Molyneux

- Google Earth

- NASA World Wind

- Johannes Schöner globe

- Planetarium

- Science On a Sphere

- Virtual globe

- Voskhod Spacecraft "Globus" IMP navigation instrument

References

- ^ More about Globe

- ^ The Earth’s circumference is (almost) exactly 40,000 km because the original definition of the metre was based precisely on this measurement – more specifically, 1/10-millionth of the distance between the poles and the equator.

- ^ Arc length#Arcs of great circles on the Earth

- ^ Savage-Smith, Emilie (1985), Islamicate Celestial Globes: Their History, Construction, and Use, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Kazi, Najma (24 November 2007). "Seeking Seamless Scientific Wonders: Review of Emilie Savage-Smith's Work". FSTC Limited. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ a b Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia 2003.

- ^ Medieval Islamic Civilization By Josef W. Meri, Jere L Bacharach, page 138-139 – available via google books – http://books.google.com/books?id=H-k9oc9xsuAC&pg=PA138&lpg=PA138&dq=al-Ma%3Fmun%3Fs+globe&source=bl&ots=TSmSiEUZXk&sig=NGzhTsbRRoSmH4UiPQCh0Y1sO_c&hl=en&ei=NMxYSvbsBeS6jAfNjNwa&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=8

- ^ Covington, Richard (2007), "The Third Dimension", Saudi Aramco World, May–June 2007: 17–21, retrieved 2008-07-06

- ^ David Woodward (1989), "The Image of the Spherical Earth", Perspecta, 25, MIT Press: 3–15 [9], JSTOR 1567135

- ^ a b Kim, Meeri (2013-08-19). "Oldest globe to depict the New World may have been discovered". Washington Post.

- ^ Soucek, Svat (1994), "Piri Reis and Ottoman Discovery of the Great Discoveries", Studia Islamica, 79 (79), Maisonneuve & Larose: 121–142 [123 & 134–6], doi:10.2307/1595839, JSTOR 1595839

- ^ Tiapchenko, Yurii. "Information Display Systems for Russian Spacecraft: An Overview". Computing in the Soviet Space Program (Translation from Russian: Slava Gerovitch).

- ^ Bliss, Laura (13 October 2014). "These tiny glass globes were all the rage in London 200 years ago". Quartz (publication). Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ http://netpbm.sourceforge.net/doc/globe.jpg

- ^ "The Mystery of Hitler's Globe Goes Round and Round", by Michael Kimmelman, September 18, 2007. Accessed September 18, 2007.