Hryhoriy Khomyshyn: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

Unlike Sheptytsky, Khomyshyn believed that the UGCC should adopt a more westward orientation, further emphasizing the Uniate Church's relationship with Rome.<ref>Stéphanie Mahieu, Vlad Naumescu. ''[https://books.google.ca/books?id=L2B3ui8h0zYC&q=khomyshyn#v=snippet&q=khomyshyn&f=false Churches In-between: Greek Catholic Churches in Postsocialist Europe]''. LIT Verlag, 2008. pg 48</ref> This meant introducing [[Latin liturgical rites]], the [[Gregorian calendar]] and a strict adherence to [[Clerical celibacy (Catholic Church)|clerical celibacy]], which were met with controversy in his eparchy.<ref name=scarecrow/><ref name=yale/> |

Unlike Sheptytsky, Khomyshyn believed that the UGCC should adopt a more westward orientation, further emphasizing the Uniate Church's relationship with Rome.<ref>Stéphanie Mahieu, Vlad Naumescu. ''[https://books.google.ca/books?id=L2B3ui8h0zYC&q=khomyshyn#v=snippet&q=khomyshyn&f=false Churches In-between: Greek Catholic Churches in Postsocialist Europe]''. LIT Verlag, 2008. pg 48</ref> This meant introducing [[Latin liturgical rites]], the [[Gregorian calendar]] and a strict adherence to [[Clerical celibacy (Catholic Church)|clerical celibacy]], which were met with controversy in his eparchy.<ref name=scarecrow/><ref name=yale/> |

||

During the 1930s, Khomyshyn was responsible for organizing the [[Christian Social Movement in Ukraine|Ukrainian Catholic People's Party]], which briefly held seats in the [[Sejm]] and [[Senate of Poland|Senate]].<ref name=scarecrow>Ivan Katchanovski, Zenon E. Kohut, Bohdan Y. Nebesio, Myroslav Yurkevich. ''[https://books.google.ca/books?id=-h6r57lDC4QC&dq=khomyshyn&q=khomyshyn#v=snippet&q=khomyshyn&f=false Historical Dictionary of Ukraine]''. Scarecrow Press, 2013. pg 263-264</ref> He is noted as being one of only a handful of members of the Catholic hierarchy in [[interwar Poland]] to publicly oppose [[anti-Semitism]]; his tolerance towards |

During the 1930s, Khomyshyn was responsible for organizing the [[Christian Social Movement in Ukraine|Ukrainian Catholic People's Party]], which briefly held seats in the [[Sejm]] and [[Senate of Poland|Senate]].<ref name=scarecrow>Ivan Katchanovski, Zenon E. Kohut, Bohdan Y. Nebesio, Myroslav Yurkevich. ''[https://books.google.ca/books?id=-h6r57lDC4QC&dq=khomyshyn&q=khomyshyn#v=snippet&q=khomyshyn&f=false Historical Dictionary of Ukraine]''. Scarecrow Press, 2013. pg 263-264</ref> He is noted as being one of only a handful of members of the Catholic hierarchy in [[interwar Poland]] to publicly oppose [[anti-Semitism]]; his tolerance towards [[Galitzianers|Galicia's Jews]] likely owing to his own experience as part of Poland's Ukrainian minority.<ref>Joanna B. Michlic. ''[https://books.google.ca/books?id=t6h2pI7o_zQC&dq=chomyszyn&q=chomyszyn#v=snippet&q=chomyszyn&f=false Poland's Threatening Other: The Image of the Jew from 1880 to the Present]''. University of Nebraska Press, 2006. pg 77-78</ref><ref>Ronald Modras. ''[https://books.google.ca/books?id=GUdgbXsA1-EC&dq=chomyszyn&q=chomyszyn#v=snippet&q=chomyszyn&f=false The Catholic Church and Antisemitism: Poland, 1933-1939]''. Routledge, 2005. pg 360-361</ref> As a result of his moderate approach to Ukrainian nationalism, he would be labeled a "sellout" by the [[OUN]] and was left fearing for his life.<ref name=yale>Myroslav Shkandrij. ''[https://books.google.ca/books?id=-WjwBQAAQBAJ&dq=khomyshyn&q=khomyshyn#v=snippet&q=khomyshyn&f=false Ukrainian Nationalism: Politics, Ideology, and Literature, 1929-1956]''. Yale University Press, 2015. pg 31-32</ref><ref>Matthew Feldman, Marius Turda, Tudor Georgescu. ''[https://books.google.ca/books?id=KcfhAQAAQBAJ&dq=khomyshyn&q=khomyshyn#v=snippet&q=khomyshyn&f=false Clerical Fascism in Interwar Europe]''. Routledge, 2013. pg 66-68</ref> |

||

Khomyshyn was first arrested in 1939 by the [[NKVD]]. A critic of the Soviet system, having called the occupied forces "fierce beasts animated by the devil,"<ref>Pierre Blet. ''[https://books.google.ca/books?id=9e36VrOxWsMC&q=chomyszyn#v=snippet&q=chomyszyn&f=false Pius XII and the Second World War: According to the Archives of the Vatican]''. Paulist Press, 1999. pg 76-77</ref> he was arrested again in April 1945, and was then deported to [[Kiev]]. In prison, he was tortured and advised to renounce the [[Union of Brest]], which he refused to do.<ref>Willem Adriaan Veenhoven, Winifred Crum Ewing, Stichting Plurale Samenlevingen. ''[http://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/2632768 Case studies on human rights and fundamental freedoms: a world survey]''. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1976. pg 477</ref> |

Khomyshyn was first arrested in 1939 by the [[NKVD]]. A critic of the Soviet system, having called the occupied forces "fierce beasts animated by the devil,"<ref>Pierre Blet. ''[https://books.google.ca/books?id=9e36VrOxWsMC&q=chomyszyn#v=snippet&q=chomyszyn&f=false Pius XII and the Second World War: According to the Archives of the Vatican]''. Paulist Press, 1999. pg 76-77</ref> he was arrested again in April 1945, and was then deported to [[Kiev]]. In prison, he was tortured and advised to renounce the [[Union of Brest]], which he refused to do.<ref>Willem Adriaan Veenhoven, Winifred Crum Ewing, Stichting Plurale Samenlevingen. ''[http://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/2632768 Case studies on human rights and fundamental freedoms: a world survey]''. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1976. pg 477</ref> |

||

Revision as of 20:52, 4 October 2015

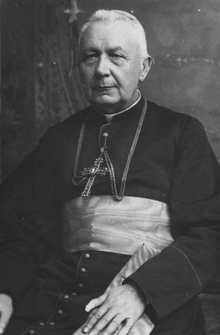

Blessed Hryhory Khomyshyn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 25 March 1867 Hadynkivtsi, Husiatyn, Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria Austrian Empire |

| Died | 17 January 1947 (aged 79) Lukyanivska Prison Kiev, Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Soviet Union |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church, Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 27 June 2001, Lviv, Ukraine by Pope John Paul II |

| Feast | December 28 |

The Blessed Hryhory Khomyshyn (also Hryhorij Khomyshyn, Ukrainian: Григорій Лукич Хомишин, Polish: Grzegorz Chomyszyn) was a Ukrainian Greek Catholic bishop and hieromartyr.

Khomyshyn was born on 25 March 1867 in the village of Hadynkivtsi, eastern Galicia, in what is now Ternopil Oblast.[1] He graduated from the seminary and was ordained a priest on 18 November 1893.[2] He continued to study theology in Vienna from 1894 to 1899, and in 1902, Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky appointed Khomyshyn the rector of the seminary in Lviv.[1] In 1904, he was ordained bishop for Stanyslaviv (now Ivano-Frankivsk) at St. George's Cathedral. Throughout his tenure, spanning over four decades, he was considered the second most powerful figure in the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.[3][4]

Unlike Sheptytsky, Khomyshyn believed that the UGCC should adopt a more westward orientation, further emphasizing the Uniate Church's relationship with Rome.[5] This meant introducing Latin liturgical rites, the Gregorian calendar and a strict adherence to clerical celibacy, which were met with controversy in his eparchy.[6][7]

During the 1930s, Khomyshyn was responsible for organizing the Ukrainian Catholic People's Party, which briefly held seats in the Sejm and Senate.[6] He is noted as being one of only a handful of members of the Catholic hierarchy in interwar Poland to publicly oppose anti-Semitism; his tolerance towards Galicia's Jews likely owing to his own experience as part of Poland's Ukrainian minority.[8][9] As a result of his moderate approach to Ukrainian nationalism, he would be labeled a "sellout" by the OUN and was left fearing for his life.[7][10]

Khomyshyn was first arrested in 1939 by the NKVD. A critic of the Soviet system, having called the occupied forces "fierce beasts animated by the devil,"[11] he was arrested again in April 1945, and was then deported to Kiev. In prison, he was tortured and advised to renounce the Union of Brest, which he refused to do.[12]

He died in the Lukyanivska Prison hospital in Kiev on 17 January 1947. He was beatified by Pope John Paul II on 27 June 2001, as one of Mykolai Charnets'kyi and the 24 companion martyrs.[2]

References

- ^ a b "Biographies of twenty five Greek-Catholic Servants of God" at the website of the Vatican

- ^ a b "Beatification of the Servants of God on June 27, 2001" at the website of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

- ^ "The Structure of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church" at the Ukrainian Catholic University's Institute of Church History website

- ^ John Pollard. The Papacy in the Age of Totalitarianism, 1914-1958. Oxford University Press, 2014. pg 306

- ^ Stéphanie Mahieu, Vlad Naumescu. Churches In-between: Greek Catholic Churches in Postsocialist Europe. LIT Verlag, 2008. pg 48

- ^ a b Ivan Katchanovski, Zenon E. Kohut, Bohdan Y. Nebesio, Myroslav Yurkevich. Historical Dictionary of Ukraine. Scarecrow Press, 2013. pg 263-264

- ^ a b Myroslav Shkandrij. Ukrainian Nationalism: Politics, Ideology, and Literature, 1929-1956. Yale University Press, 2015. pg 31-32

- ^ Joanna B. Michlic. Poland's Threatening Other: The Image of the Jew from 1880 to the Present. University of Nebraska Press, 2006. pg 77-78

- ^ Ronald Modras. The Catholic Church and Antisemitism: Poland, 1933-1939. Routledge, 2005. pg 360-361

- ^ Matthew Feldman, Marius Turda, Tudor Georgescu. Clerical Fascism in Interwar Europe. Routledge, 2013. pg 66-68

- ^ Pierre Blet. Pius XII and the Second World War: According to the Archives of the Vatican. Paulist Press, 1999. pg 76-77

- ^ Willem Adriaan Veenhoven, Winifred Crum Ewing, Stichting Plurale Samenlevingen. Case studies on human rights and fundamental freedoms: a world survey. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1976. pg 477

External links

- Blessed Hryhorii Khomyshyn at CatholicSaints.info

- Bishop Bl. Grigorij Chomyszyn (Khomyshyn) at Catholic-Hierarchy.org

- Bl. Gregory Chomyszyn (in Polish)

- "Story of faith, of secrecy, of death -- and life", 2001 article in the Baltimore Sun

- 1867 births

- 1947 deaths

- People from Husiatyn Raion

- People from the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

- Ukrainian Austro-Hungarians

- Bishops of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

- 20th-century Eastern Catholic bishops

- Ukrainian politicians before 1991

- Polish anti-fascists

- Ukrainian anti-communists

- Inmates of Lukianivka Prison

- Ukrainian people who died in prison custody

- Prisoners who died in Soviet detention

- Eastern Catholic martyrs

- 20th-century Roman Catholic martyrs

- Ukrainian beatified people

- Eastern Catholic beatified people

- Beatifications by Pope John Paul II