Ajax (play): Difference between revisions

Clockchime (talk | contribs) ref added, Moore on page 2 says it is not at all to be considered immature |

Sangdeboeuf (talk | contribs) Formatting citations for clarity, attributing opinion to source per WP:WikiVoice Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

| genre = [[Tragedy]] |

| genre = [[Tragedy]] |

||

}} |

}} |

||

[[Sophocles]]'s '''Ajax''' or '''Aias''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|eɪ|dʒ|æ|k|s}} or {{IPAc-en|ˈ|aɪ|.|ə|s}}; {{lang-grc|Αἴας}} {{IPA-el|a͜í.aːs|}}, gen. Αἴαντος) is a Greek tragedy written in the 5th century BC. ''Ajax'' may be the earliest of the seven plays by Sophocles that have survived, but it is not at all an immature work.<ref>Moore, John, trans. “Introduction to Ajax”. |

[[Sophocles]]'s '''Ajax''' or '''Aias''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|eɪ|dʒ|æ|k|s}} or {{IPAc-en|ˈ|aɪ|.|ə|s}}; {{lang-grc|Αἴας}} {{IPA-el|a͜í.aːs|}}, gen. Αἴαντος) is a Greek tragedy written in the 5th century BC. According to John Moore, ''Ajax'' may be the earliest of the seven plays by Sophocles that have survived, but it is not at all an immature work.<ref name="Moore">Moore, John, trans. “Introduction to Ajax”. Grene, David; Lattimore, Richmond, eds. (1969). ''Sophocles II: Ajax, The Women of Trachis, Electra & Philoctetes (The Complete Greek Tragedies)'', 2nd Edition. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226307862. page 2.</ref> Moore writes that the play appears to belong to the same period as Sophocles's ''Antigone'', which was produced in 442 or 441 BC, when Sophocles was 55 years old, and had been producing plays for a quarter of a century.<ref name="Moore"/> It depicts the fate of the warrior [[Ajax (mythology)|Ajax]] after the events of the ''[[Iliad]]'', but before the end of the [[Trojan War]]. |

||

==Plot== |

==Plot== |

||

Revision as of 21:44, 2 July 2016

| Ajax | |

|---|---|

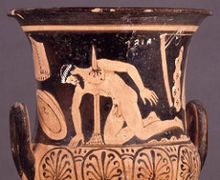

The suicide of Ajax. Etrurian red-figured calyx-krater, ca. 400–350 BC. | |

| Written by | Sophocles |

| Chorus | Sailors from Salamis |

| Characters | Athena Odysseus Ajax Tecmessa Messenger Teucer Menelaus Agamemnon |

| Mute | Attendants Servants Soldiers Eurysaces |

| Place premiered | Athens |

| Original language | Ancient Greek |

| Genre | Tragedy |

Sophocles's Ajax or Aias (/ˈeɪdʒæks/ or /ˈaɪ.əs/; Ancient Greek: Αἴας [a͜í.aːs], gen. Αἴαντος) is a Greek tragedy written in the 5th century BC. According to John Moore, Ajax may be the earliest of the seven plays by Sophocles that have survived, but it is not at all an immature work.[1] Moore writes that the play appears to belong to the same period as Sophocles's Antigone, which was produced in 442 or 441 BC, when Sophocles was 55 years old, and had been producing plays for a quarter of a century.[1] It depicts the fate of the warrior Ajax after the events of the Iliad, but before the end of the Trojan War.

Plot

The great warrior, Achilles, has been killed in battle. The man who now can be considered the greatest warrior should be given Achilles’ armor, but the two kings, Agamemnon and Menelaos, award it instead to Odysseus. Ajax becomes furious about this and decides to kill them. However Athena steps in and deludes Ajax into killing instead the spoil of the Greek army, which includes cattle as well as the herdsman. Suddenly Ajax comes to his senses and realizes what he has done. Overwhelmed by shame, he decides to commit suicide. His concubine, Tecmessa, pleads for him not to leave her and their child, Eurysakes, unprotected. Ajax then gives his son his shield, and leaves the house saying that he is going out to purify himself and to bury the sword given to him by Hector. Teucer, Ajax’s brother, arrives. Teucer has learned from the prophet, Kalchas, that Ajax should not be allowed to leave his tent until the end of the day or he will die. Tecmessa and soldiers then try to find Ajax, but they are too late. Ajax has impaled himself upon his sword. Before his suicide, Ajax calls for vengeance against the sons of Atreus (Menelaus and Agamemnon) and the whole Greek army. Tecmessa is the first one to discover Ajax’s body. Teucer then arrives and orders that Ajax’s son be brought to him so that he will be safe from foes. Menelaus appears and orders the body not to be moved.

The last part of the play, is taken up with an angry dispute regarding what to do with Ajax’s body. The two kings, Agamemnon and Menelaos, want to leave the body unburied for scavengers to have, and Ajax’s half-brother Teucer wants to bury it. Odysseus arrives and persuades Agamemnon and Menelaos to allow Ajax a proper funeral. Odysseus points out that even one's enemies deserve respect in death. The play ends with Teucer making arrangements for the burial.

"Ajax" or "Aias"

The Greek name of the play in the Greek alphabet is “Αἴας“. “Ajax” is the Latinized version, and “Aias” is the English transliteration from the original Greek. There has been an orthographic tradition that proper nouns of Ancient Greek are first Latinized before entering the English language. And there is a recent trend to break with that tradition by going back to a transliteration of the original Greek. It is hardest to let go of the Latinized version when a name in that form has become widely recognized and rooted in English.[2][3]

The text of this play presents a particular issue that translators need to consider. The character Ajax (or Aias) points out that his own name has an onomatopoeic resemblance to a wailing cry of lament: “aiai!”[4]

Here are two examples that show that passage being handled by different translators:

Aiai! My name is a lament!

Who would have thought it would fit

so well with my misfortunes!

Now truly I can cry out -- aiai! --

two and three times in my agony.[5]

Aiee, Ajax! My name says what I feel;

who'd have believed that pain and I'd be one;

Aiee, Ajax! I say it twice,

and then again, aiee, for what is happening.[6]

Interpretations

Ajax is a heroic figure, whose strength, courage and quick-thinking are almost superhuman. The stories of him coming to the rescue of his fellow man in dire moments are the stuff of legend. Yet, as in this play, he and others also suffer from those same qualities when Ajax becomes proud, stubborn and hot tempered. Some critics consider that the Greek gods are portrayed as just, and when Ajax suffers it is a learning-experience for him. Other critics instead consider that Ajax is heroically in defiance of the unjust and capricious gods. Ajax’s murderous intentions in this play are not softened by the playwright, and the difficult aspects of his character are fully depicted. But Sophocles is profoundly sympathetic of the greatness of Ajax, and appreciative of Ajax’s brave realization that suicide is the only choice — if he is to maintain his conception of honor and his sense of self.[7]

One interpretation sees the play as composed in two distinct parts. The first part is steeped in the old world, of Kings and heroes, and the second part resembles more the democratic world of Sophocles’ Greece, and is marked by an imperfect debate of contending ideas. The play may be seen as an important epoch-spanning work, that raises complex questions, including: How does fifth century Greece advance from the old world into the new? It clings to and reveres the old, in its stories and thoughts; and yet the new democratic order is important and vital, and so completely different from the past. Ajax, with his brute force has been a great warrior-hero of the old world, but the war itself has changed and become a quagmire, and what’s needed now is a warrior who is intelligent, someone like Odyseus. Ajax must still be respected, and the end of the play demonstrates respect and human decency with the promise of a proper burial.[8]

Another interpretation sees the play as primarily a character study of Ajax, who, when he first appears covered in the blood of the animals he in his madness has killed, presents an image of total degradation; the true action of the play is how this image is transformed, and how Ajax recovers his heroic power and humanity. The play personifies in Ajax an affirmation of what is heroic in life.[9]

Bernard Knox considers Ajax’s speech on “time” to be “so majestic, remote and mysterious, and at the same time so passionate, dramatic and complex” that if this were the only writing we had of Sophocles, he would still be considered “one of the world’s greatest poets.”[10] The speech begins:

Long rolling waves of time

bring all things to light

and plunge them down again

in utter darkness.[11]

Translations

- Richard Claverhouse Jebb, 1896[12]

- John Moore, 1969[13]

- Hugh Lloyd-Jones, 1993[14]

- James Scully, 2011[15]

- Frederic Raphael and Kenneth McLeish, 1998 [16]

- R. C. Trevelyan, 1919[17]

- David Raeburn, 2008.[18]

- John Tipton, 2008[19]

- George Theodoridis, 2009 – prose: full text

Adaptations

- Bryan Doerris – Through his company Theatre of War, Doerris presents readings of Ajax and other plays to American military bases, to spark dialogue about PTSD.

- British playwright Timberlake Wertenbaker's play 'Our Ajax' had its premier at the Southwark Playhouse, London, in November 2013. This play, inspired by Sophocles' tragedy, has a contemporary military setting, with references to modern warfare including the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Wertenbaker is reported to have developed this new work from interviews with current and former servicemen and women.

- Robert Auletta, 1986 – modern adaptation.[20]

References

- ^ a b Moore, John, trans. “Introduction to Ajax”. Grene, David; Lattimore, Richmond, eds. (1969). Sophocles II: Ajax, The Women of Trachis, Electra & Philoctetes (The Complete Greek Tragedies), 2nd Edition. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226307862. page 2.

- ^ Sophocles. Ajax. Jebb, Richard Claverhouse. The Ajax. Volume 7 of Sophocles: The Plays and Fragments. The Cambridge University Press, 1896.

- ^ Sophocles. Bagg, Robert. Scully, James. Translation.The Complete Plays of Sophocles; A New Translation. Harper Perennial, 2011. ISBN 978 0 06 202034 5.

- ^ Jenkins, Thomas E. Antiquity Now: The Classical World in the Contemporary American Imagination. Cambridge University Press, 2015. ISBN 9780521196260. page 90

- ^ Sophocles. Golder, Herbert, translator. Aias (Ajax) Greek tragedy in new translations. Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 9780195128192.

- ^ Sophocles. Raphael, Frederick; McLeish, Kenneth; translators. Ajax University of Pennsylvania Press (1998) ISBN 9780812234459

- ^ Sophocles. Lloyd-Jones, Hugh. ed. & trans. Sophocles; Ajax, Electra, Oedipus Tyrannus. “Introduction”. Loeb Classical Library. Harvard Univ. Press, 1994. ISBN 0-674-99557-0

- ^ Sophocles. Bagg, Robert. Scully, James. Translation.The Complete Plays of Sophocles; A New Translation. Harper Perennial, 2011. ISBN 978 0 06 202034 5.

- ^ Moore, John, trans. “Introduction to Ajax”. Sophocles. Ajax. Sophocles II: Ajax, The Women of Trachis, Electra & Philoctetes (The Complete Greek Tragedies) 2nd Edition. Edited by David Grene and Richmond Lattimore. University of Chicago Press. 1969. ISBN 978-0226307862. page 2

- ^ Knox, Bernard. “The Ajax of Sophocles”, Word and Action: Essays on the Ancient Greek Theater. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979. Page 125

- ^ Sophocles. Bagg, Robert. Scully, James. Translation.The Complete Plays of Sophocles; A New Translation. Harper Perennial, 2011. ISBN 978 0 06 202034 5. page 52

- ^ Sophocles. Ajax. Jebb, Richard Claverhouse. The Ajax. Volume 7 of Sophocles: The Plays and Fragments. The Cambridge University Press, 1896.

- ^ Sophocles. Ajax. Sophocles II: Ajax, The Women of Trachis, Electra & Philoctetes (The Complete Greek Tragedies) 2nd Edition. Edited by David Grene and Richmond Lattimore. Univerisy of Chicago Press. 1969. ISBN 978-0226307862.

- ^ Sophocles. Sophocles, Volume I. Ajax. Electra. Oedipus Tyrannus (Loeb Classical Library No. 20) ISBN 978-0674995574

- ^ Sophocles. Bagg, Robert. Scully, James. Translation.The Complete Plays of Sophocles; A New Translation. Harper Perennial, 2011. ISBN 978 0 06 202034 5.

- ^ Sophocles. Sophocles, 1 : Ajax, Women of Trachis, Electra, Philoctetes (Penn Greek Drama Series) University of Pennsylvania Press (May 1, 1998) ISBN 978-0812216530

- ^ Trevelyan, R.C. The Ajax of Sophocles. Cornell University Library (June 25, 2009) ISBN 978-1112068171

- ^ Sophocles. Electra and Other Plays (Penguin Classics). June 24, 2008. ISBN 978-0140449785

- ^ Sophocles. Ajax. Tipton, John. translator. Chicago: Flood Editions (2008) ISBN 978-0-9787- 4675-9

- ^ [1] Sullivan, Dan. Stage Review : “Sellars' Ajax--more Than Games”. Los Angeles Times. 2 September 1986

Further reading

- Grant, Michael. "Sophocles." Greek and Latin Authors 800 BC-AD 1000. New York: HW Wilson Company, 1980. 397–402. Print.

External links

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Αἴας

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Αἴας- http://classics.mit.edu/Sophocles/ajax.html Text of Ajax translated by R. C. Trevelyan

Ajax public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Ajax public domain audiobook at LibriVox