Jan Patočka: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Lenny Olsen (talk | contribs) →External links: unverifiable broken link |

||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

* [http://www.ajp.cuni.cz/index_e.html The Jan Patočka Archive in Prague] |

* [http://www.ajp.cuni.cz/index_e.html The Jan Patočka Archive in Prague] |

||

* The [http://www.iwm.at/research/patocka/ Jan Patočka Archive, Vienna, Institute of Human Sciences] |

* The [http://www.iwm.at/research/patocka/ Jan Patočka Archive, Vienna, Institute of Human Sciences] |

||

*Daniel Epstein, [http://www.acheret.co.il/en/?cmd=articles.300&act=read&id=1897 Let us not despair of Europe, let us not despair of ourselves], [http://www.acheret.co.il/en Eretz Acheret] Magazine |

<!-->*Daniel Epstein, [http://www.acheret.co.il/en/?cmd=articles.300&act=read&id=1897 Let us not despair of Europe, let us not despair of ourselves], [http://www.acheret.co.il/en Eretz Acheret] Magazine ...Comment:Is this broken link to be fixed or just here by mistake?<--> |

||

=== Bibliography === |

=== Bibliography === |

||

Revision as of 19:03, 29 August 2016

Jan Patočka | |

|---|---|

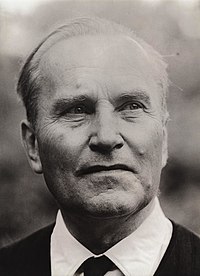

Jan Patočka (1971) Photo: Jindřich Přibík | |

| Born | 1 June 1907 |

| Died | 13 March 1977 (aged 69) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Phenomenology |

Jan Patočka (1 June 1907 – 13 March 1977) was a Czech philosopher. Due to his contributions to phenomenology and the philosophy of history he is considered one of the most important philosophers of the 20th century. Having studied in Prague, Paris, Berlin and Freiburg, he was one of the last pupils of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. During his studies in Freiburg he was also tutored by Eugen Fink, a relation which eventually turned into a lifelong philosophical friendship.

Early life

Patočka attended Jan Neruda Grammar School.

Works

His works mainly dealt with the problem of the original, given world (Lebenswelt), its structure and the human position in it. He tried to develop this Husserlian concept under the influence of some core Heideggerian themes (e.g. historicity, technicity, etc.) On the other hand, he also criticised Heideggerian philosophy for not dealing sufficiently with the basic structures of being-in-the-world, which are not truth-revealing activities (this led him to an appreciation of the work of Hannah Arendt). From this standpoint he formulated his own original theory of "three movements of human existence": 1) receiving, 2) reproduction, 3) transcendence. He also translated many of Hegel's and Schelling's works into Czech.

Apart from his writing on the problem of the Lebenswelt, he wrote interpretations of Presocratic and classical Greek philosophy and several longer essays on the history of Greek ideas in the formation of our concept of Europe. He also entered into discussions about modern Czech philosophy, art, history and politics.

Patočka's Heretical Essays in the Philosophy of History is analyzed at length and with much care in Jacques Derrida's important book The Gift of Death. Derrida was the most recent person who wrote or conversed with Patočka's thought; Paul Ricoeur and Roman Jakobson (who respectively wrote the preface and afterword to the French edition of the Heretical Essays...) are two further examples.

During the years 1939–1945, when the Czech universities were closed, as well as between 1951–1968 and from 1972 on, Patočka was banned from teaching. Only a few of his books were published and most of his work circulated only in the form of typescripts kept by students and disseminated mostly after his death. Along with other banned intellectuals he gave lectures at the so-called "Underground University", which was an informal institution that tried to offer a free, uncensored cultural education. In January 1977 he became one of the original signatories and main spokespersons for the Charter 77 (Charta 77) human rights movement in Czechoslovakia. For the three months after the Charter was released he was intensely active writing and speaking about the meaning of the Charter, in spite of his deteriorating health. He was also interrogated by the police regarding his involvement with the Charter movement, and on March 3, 1977 he was held by the police for ten hours, who had claimed that he would be allowed to speak in his role as a Charter spokesperson with a high-ranking official (in fact, this was a pretext to keep him from attending a reception at the West German embassy[1]). He fell ill that evening and was taken to the hospital, where his health briefly improved, enabling him to give one final interview with Die Zeit and to write one final essay entitled "What We Can Expect from Charter 77." On March 11 he relapsed, and on March 13 he died of apoplexy, at the age of 69.

His brother František Patočka was a microbiologist.

List of works

- The Natural World As a Philosophical Problem [Přirozený svět jako filosofický problém]

- An Introduction to Husserl's Phenomenology [Úvod do Husserlovy fenomenologie]

- Aristotle, his Predecessors and his Heirs [Aristoteles, jeho předchůdci a dědicové]

- Body, Community, Language, World [Tělo, společenství, jazyk, svět]

- Negative Platonism [Negativní platónismus]

- Plato and Europe [Platón a Evropa]

- Who are the Czechs? [Co jsou Češi?]

- Care for the Soul [Péče o duši]

- Heretical Essays in the Philosophy of History [Kacířské eseje o filosofii dějin]

In English

- “Wars of the Twentieth Century and the Twentieth Century as War”. Telos 30 (Winter 1976-77). New York: Telos Press.

- Body, Community, Language, World. Translated by Erazim Kohák. Edited by James Dodd. Chicago, IL: Open Court, 1998.

- Heretical Essays in the Philosophy of History. Translated by Erazim Kohák. Edited by James Dodd. Chicago, IL: Open Court, 1996.

- An Introduction to Husserl's Phenomenology. Translated by Erazim Kohák. Edited by James Dodd. Chicago, IL: Open Court, 1996.

- Plato and Europe. Translated by Petr Lom. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002.

References

- ^ John Bolton, Worlds of Dissent (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012), p. 159.

Further reading

- Renaud Barbaras, Le mouvement de l'existence. Etudes sur la phénoménologie de Jan Patočka, Les Editions de la transparence, 2007

- Dalibor Truhlar, Jan Patočka. Ein Sokrates zwischen Husserl und Heidegger, Sonderpublikation des Universitätszentrums für Friedensforschung Wien, 1996

- Erazim Kohák, Jan Patočka: Philosophy and Selected writings.

- Jacques Derrida, The Gift of Death

- Edward F. Findlay, Caring for the soul in a postmodern age : politics and phenomenology in the thought of Jan Patočka

- Marc Crépon, Altérités de l'Europe

- Jan Patočka and the European Heritage, Studia Phaenomenologica VII (2007) - Ivan Chvatik (guest editor)