Zappo Zap: Difference between revisions

KolbertBot (talk | contribs) m Bot: HTTP→HTTPS |

|||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

The Zappo Zap settlement near Luluabourg prospered and the Zappo Zaps became the main allies of King Leopold's forces in Kasai. In 1890 they helped drive Kalamba away from Luluabourg, in 1891 they defeated two Angolan caravans that threatened the post from the south and in April 1895 they again repelled Kalamba from the post. In July 1895 they helped put down a rebellion by the Luluabourg garrison. |

The Zappo Zap settlement near Luluabourg prospered and the Zappo Zaps became the main allies of King Leopold's forces in Kasai. In 1890 they helped drive Kalamba away from Luluabourg, in 1891 they defeated two Angolan caravans that threatened the post from the south and in April 1895 they again repelled Kalamba from the post. In July 1895 they helped put down a rebellion by the Luluabourg garrison. |

||

The Zappo Zaps provided mistresses to most of the Europeans, gaining further influence in the process. |

The Zappo Zaps provided mistresses to most of the Europeans, gaining further influence in the process. |

||

They became the owners of large commercial plantations operated by slave labour and engaged in the slave trade to a small extent, which the authorities chose to ignore. But their main commercial |

They became the owners of large commercial plantations operated by slave labour and engaged in the slave trade to a small extent, which the authorities chose to ignore. But their main commercial activity was the ivory and rubber trade, bringing their goods to the trading centers at Lusambo, [[Luebo]] and [[Bena Makima]].{{sfn|Vansina|2010|p=26}} |

||

==Kuba massacre== |

==Kuba massacre== |

||

Revision as of 15:53, 16 October 2017

The Zappo Zap were a group of Songye people from the eastern Kasai region in what today is the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They acted as allies of the Congo Free State authorities of the King of the Belgians, while trading in ivory, rubber and slaves.[1] In 1899 they were sent out by the colonial administration to collect taxes. They massacred many villagers, causing an international outcry.[2]

Traditional lifestyle

According to the missionary William Henry Sheppard, the Zappo Zap people all had tattoed faces and had filed their teeth to sharp points. They dressed only in two minute pieces of palm fiber cloth. They were armed with long spears and with poisonous and steel arrows. Their iron weapons gave them an advantage in warfare, and when armed with guns the advantage was decisive.[3] The Songa people, to whom the Zappo Zaps belonged, also used battle axes (kasuyu or zappozap).[4][clarification needed][5]

The Zappo Zaps worked as mercenaries for whoever was in power. They had been engaged in slave raiding long before the Europeans arrived, burning villages, partly eating bodies and selling hundreds of slaves to the Arabs each year in exchange for guns, ammunition and other manufactured goods.[3] The Zappo Zaps did not restrict their cannibalism to ceremonial occasions, as in other cultures. Instead they hunted humans for food even when other game was plentiful. They considered human flesh a delicacy, and ate all parts of the body, even brains and eyeballs. They fried the meat in the same way as bacon.[6]

European contacts

In March 1883 Hermann Wissmann, the first European traveller in the region, gave the name "Zappo Zap" to a leader known as Nsapu Nsapu who ruled over the town of Mpengie, part of the Ben'Eki kingdom. This was a settlement with more than a thousand people, many of them slave warriors, to the east of the Sankuru River between Kabinda and Lusambo. The group were thriving through slave raiding and trading with caravans from the Arab and Swahili towns on the Lualaba River to the east and from Bihe in Angola to the southwest.[7]

In 1883 Zappo Zap felt strong enough to challenge the king of the Ben'Eki, leading to a civil war that drew in all the slavers of the region. In 1886, he was forced to retreat to a location near Lusambo, where he built an impressive station. In 1887 he lost a battle on the right bank of the Sankuru and was forced to cross the river with his 3,000 followers. He met the Congo Free State commander Paul Le Marinel near Lusambo, with Chief Mukenge Kalamba of the Lulua, both retreating westward from the Lualaba.[7]

When Herman Wissman met Zappo Zap in 1887 he was dressed with a turban, shirt and pants in the Arab fashion. The missionary Lapsley, who met Zappo Zap's son later, said he had a cloth tied about his head and was clothed from shoulder to knee. Lapsley gave Zappo Zap a gift of brass wire and cloth, and received some young slaves in return. Lapsley appreciated the gift, later releasing the slaves and educating them at the Luebo mission.[6] Zappo Zap died in 1888 and was succeeded by his son, who also came to be known as Zappo Zap, and who moved with all his people to settle near the Luluabourg post in 1889.[7] The second Zappo Zap died in 1894. His brother succeeded him and took the name Zappo Zap, which had become the title of the leader of the Zappo Zap people.[1]

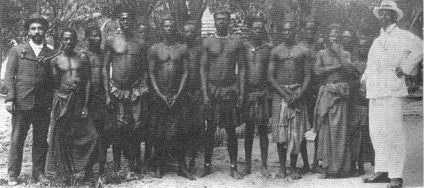

In some ways, the Zappo Zaps seemed civilized to the missionaries. They wore western-style clothing, lived in square houses and could speak both English and French. On the other hand, with their plucked eyebrows and eyelashes, filed teeth and traditions of slaving and cannibalism they were stereotypes of the Western view of African savages.[8] Lapsley said the Zappo Zaps were "magnificent men and handsome women, and carry themselves quite as an aristocracy". However, he was disturbed by the way in which small girls danced lasciviously in imitation of older women.[9]

Colonial allies

The Zappo Zap settlement near Luluabourg prospered and the Zappo Zaps became the main allies of King Leopold's forces in Kasai. In 1890 they helped drive Kalamba away from Luluabourg, in 1891 they defeated two Angolan caravans that threatened the post from the south and in April 1895 they again repelled Kalamba from the post. In July 1895 they helped put down a rebellion by the Luluabourg garrison. The Zappo Zaps provided mistresses to most of the Europeans, gaining further influence in the process. They became the owners of large commercial plantations operated by slave labour and engaged in the slave trade to a small extent, which the authorities chose to ignore. But their main commercial activity was the ivory and rubber trade, bringing their goods to the trading centers at Lusambo, Luebo and Bena Makima.[1]

Kuba massacre

In 1899 the commander of Luluabourg, Dufour, decided to demand rubber from the people of the Kuba Kingdom in payment of taxes. He asked Zappo Zap to provide the force needed. Zappo Zap delegated the job to his ally Mulumba Nkusu.[10] About 500 warriors armed with guns went to the Pyang region of the Kuba Kingdom where they built a stockade. They summoned the local chiefs and demanded sixty slaves as well as herds of goats, baskets of food and 2,500 balls of rubber. When the chiefs refused to pay this huge tribute the stockade gate was closed and the chiefs were massacred. The Zappo Zaps then killed, looted and burned villages throughout the Pyang country.[11] At least fourteen villages were destroyed, and many people fled to the bush in the middle of the rainy season.[2]

The Reverend William Henry Sheppard was sent from the Southern Presbyterian mission at Luebo to investigate.[2] Sheppard's journal of 14–15 September 1899 describes how he pretended to be friendly and through asking casual questions of Mulumba Nkusu, whom he knew, obtained the story of what had happened and was shown the remains.[12]

He saw evidence of cannibalism, counted eighty-one right hands that had been cut off and were being dried before being taken to show the State officers what the Zappo Zaps had achieved and found sixty women confined in a pen.[2] The missionaries protested, and to their surprise the Free State officials responded, ordering the release of the women prisoners and the arrest of M'lumba. M'lumba was also puzzled at being arrested, saying he had only done what was asked of him.[13]

In January 1900 a member of the Executive Committee for Foreign Missions acknowledged receiving reports and letters about the Zappo Zap atrocities from the missionaries, but reminded the mission of "the necessity of the utmost caution, in making representations regarding these matters to those in authority, or in publishing them to the world, to observe all proper deference to 'the powers that be,' and to avoid anything that might give any color to a charge of doing or saying things inconsistent with its purely spiritual and non-political character".[14]

However, in January 1900 the New York Times published a report giving Sheppard's findings. It detailed the atrocities in the Bena Kamba country and said that the Zappo Zaps were acting for the Congo Free State. It went on "They are sent out to collect rubber, ivory, slaves and goats as tribute from the people, and can then plunder, burn and kill for their own amusement and gain".[2] The massacre caused an uproar against Dufour and the Congo Free State.[10] When Mark Twain published his King Leopold's Soliloquy five years later, he mentioned Sheppard by name and referred to his account of the massacre.[15] Sir Arthur Conan Doyle mentioned the Zappo Zap in his 1909 book The Crime of the Congo, but said they were forced to extract rubber for King Leopold's forces or they would in turn suffer punishment.[16]

Despite the help the Zappo Zaps had given, it was not until 1910 that Leopold's successors, the Belgian Congolese colonial authorities, had brought the Kuba Kingdom under control and established a military post in the royal capital.[17] The state stopped using the Zappo Zap as auxiliaries and they lost their special position, particularly after the Belgian State took over the colony in 1908.[10] The Songye today are known for metallic decoration on wooden statuary. The Zappo Zap are considered to be the most skillful smiths of the Songye, the most skillful in the DRC and perhaps in Africa.[18]

References

- ^ a b c Vansina 2010, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e Massacre in Congo State.

- ^ a b Phipps 2002, p. 137.

- ^ Phipps 2002, p. 2020.

- ^ African Art - Life Force...

- ^ a b Phipps 2002, p. 138-139.

- ^ a b c Vansina 2010, p. 25.

- ^ Campbell 2007, p. 156.

- ^ Edgerton 2002, p. 119.

- ^ a b c Vansina 2010, p. 27.

- ^ Vansina 2010, p. 73.

- ^ Benedetto 1996, pp. 121ff.

- ^ Edgerton 2002, p. 135.

- ^ Nakayama & Halualani 2011, p. 286.

- ^ Thompson 2007, p. 19.

- ^ Doyle 2008, p. 155.

- ^ Shoup 2011, p. 156.

- ^ Herbert 2003, p. 226.

Sources

- "African Art – Life Force at the Anvil – pg 46". ArtMetal. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- Benedetto, Robert (1996). "Interview With Chief M'lumba N'kusa Concerning the Zappo Zap Raid". Presbyterian reformers in Central Africa: a documentary account of the American Presbyterian Congo Mission and the human rights struggle in the Congo, 1890-1918. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10239-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Campbell, James T. (2007). Middle Passages: African American Journeys to Africa, 1787-2005. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-311198-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Doyle, Arthur Conan (2008). The Crime of the Congo. ReadHowYouWant.com. ISBN 1-4270-5456-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Edgerton, Robert B. (2002). The troubled heart of Africa: a history of the Congo. Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-30486-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Herbert, Eugenia W. (2003). Red gold of Africa: copper in precolonial history and culture. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-09604-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Massacre in Congo State". New York Times. January 5, 1900. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- Nakayama, Thomas K.; Halualani, Rona Tamiko (2011). The Handbook of Critical Intercultural Communication. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 1-4443-9067-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Phipps, William E. (2002). William Sheppard: Congo's African American Livingstone. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-50203-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shoup, John A. (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-59884-362-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, T. Jack (June 29, 2007). "Capturing the Image: African Missionary Photography as Enslavement and Liberation" (PDF). Yale University Divinity School. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vansina, Jan (2010). Being colonized: the Kuba experience in rural Congo, 1880-1960. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-23644-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)