Sukanasa

In Hindu temple architecture a sukanasa (Sanskrit: शुकनास, IAST: śukanāsa) or sukanasi is an external ornamented feature over the entrance to the garbhagriha or inner shrine. It sits on the face of the sikhara tower (in South India, the vimana) as a sort of antefix.[2] The forms of the sukanasa can vary considerably, but it normally has a vertical face, very often in the form of a large gavaksha or "window" motif, with an ornamental frame above and to the sides, forming a roughly triangular shape.[3] In discussing temples in Karnataka local authors tend to use "sukanasi" (the preferred form in these cases) as a term for the whole structure of the antarala or ante-chamber from the floor to the top of the sukanasa roof above.[4]

It often contains an image of the deity to whom the temple is dedicated inside this frame, or other figurative subjects. The vertical face may be the termination of a horizontally-projecting structure of the same shape,[5] especially in temples with an antarala or ante-chamber between the mandapa or public worship hall and the garbhagriha. In these cases the projection is over the antarala.[6] Some temples have large gavaksha motifs, in effect sukanasas, on all four faces of the shikara, and there may be two tiers of sukanasa going up the tower. Sukasanas are also often found in Jain temples.[7]

The name strictly means "parrot's beak", and is often referred to as the "nose" of the temple superstructure, as part of the understanding of the temple as representing in its various parts the anatomy of the deity.[8] Various early texts set out proportions for the shape of the sukasana, centred on a circular gavaksha, and its size in proportion to the rest of the temple, especially the height of the shikara. They vary and in any case are not always followed.[9]

Especially in the south, the sukanasa may be topped by a kirtimukha head, the open-mouthed monster swallowing or vomiting the rest of the motif below.[10] As with the gavaksha, the motif represents a window through which the light of the deity shines out across the world.[11]

History

[edit]The sukanasa appears to develop from later forms of the large "chaitya arch" on the outside facade of Buddhist chaitya halls. Initially these were a large practical window admitting light to the interior, and reflecting the shape of the curved internal roof, based on timber and thatch predecessors. Later, these large motifs developed into a setting for sculpture that was largely "blind" or not actually an opening in the wall. Both phases now only survive in rock-cut "cave temples" at sites such as the Ajanta Caves, where the first type can be seen at Caves 9, 10, 19, and 26, and Ellora, where Cave 10 shows the second type.

According to Adam Hardy, "possibly the first use of a sukanasa in a Dravida temple" is the Parvati temple, Sandur (7–8th century), using his terminology where "Karnataka Dravida" architecture is treated as a form of Dravidian architecture; others describe this as Badami Chalukya architecture or similar terms.[12]

In Hoysala architecture, the sukanasa is typically brought forward over an antarala, and the royal emblem of the Hoysala Empire, the mythical founder Sala stabbing a lion (according to the legend a tiger, but the two are not distinguished in Indian art), often stands over the barrel roof as sculpture in the round.[13] Among other places, this can be seen at the Bucesvara Temple, Koravangala, both temples at the Nageshvara-Chennakeshava Temple complex, Mosale, and the Kedareshvara Temple, Balligavi.[14]

-

Bucesvara Temple, Koravangala from the side. Projecting sukanasa with free-standing sculpture on the top of the Hoysala emblem.

-

The partly dismantled Galaganatha Temple, Pattadakal, where the antefix stones of the sukanasa are missing.

-

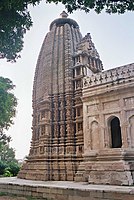

Latina shikhara of Adinatha temple, Khajuraho, with very elaborate sukanasa.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- Foekema, Gerard, A Complete Guide to Hoysala Temples, Abhinav, 1996 ISBN 81-7017-345-0, google books

- Hardy, Adam, Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation : the Karṇāṭa Drāviḍa Tradition, 7th to 13th Centuries, 1995, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 8170173124, 9788170173120, google books

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- Krishna Murthy, M.S., "Jaina Monuments In Southern Karnataka", Ahimsa Foundation (www.jainsamaj.org)

- Kramrisch, Stella, The Hindu Temple, Volume 1, 1996 (originally 1946), ISBN 8120802225, 9788120802223, google books

- Michell, George, The Penguin Guide to the Monuments of India, Volume 1: Buddhist, Jain, Hindu, 1989, Penguin Books, ISBN 0140081445