Treaty of Bosque Redondo

The Treaty of Bosque Redondo (Spanish for "Round Forest") also the Navajo Treaty of 1868 or Treaty of Fort Sumner, Navajo Naal Tsoos Sani or Naaltsoos Sání[1][2][a]) was an agreement between the Navajo and the US Federal Government signed on June 1, 1868. It ended the Navajo Wars and allowed for the return of those held in internment camps at Fort Sumner following the Long Walk of 1864.[4]: 699 The treaty effectively established the Navajo as a sovereign nation.[5]: 58

Background

Following conflicts between the Navajo and US forces, and scorched earth tactics employed by Kit Carson, which included the burning of tribal crops and livestock, James Henry Carleton issued an order in 1862 that all Navajo would relocate to the Bosque Redondo Reservation[b] near Fort Sumner, in what was then the New Mexico Territory. Those who refused would face "immediate military action".[8]: 38 [1] This culminated in the Long Walk of 1864, wherein some 8,000 to 10,000 Navajo and Apache, including women and children, were forced to march over 350 miles from their native land near the Four Corners area.[8]: 38 [9]: 364

According to Carleton's planned assimilation, while at Bosque Redondo the Navajo would "become farmers, would live in villages, and would be instructed in Christianity and other American practices".[9]: 364 However the site, personally chosen by Carleton, proved difficult and expensive to maintain, and the conditions for those interned there deplorable. Farming was impractical in the poor quality soil, with inadequate irrigation, and the unpredictable and occasionally destructive waters of the Pecos River.[10]: 465 [11] What crops grew were destroyed by worms and floods. Many died of disease and starvation.[4]: 699 [2] According to one estimate, from March to December 1865, the total population dropped from approximately 9,000 to some 6,000.[12]

Meanwhile, Bosque Redondo was incurring great expense to the government to maintain. In 1865 the cost of feeding and guarding the Navajo reached some $1,250,000.[11]: 265 [c] General William T. Sherman wrote to General James Carleton that the government "cannot and will not maintain" this "extravagant system of expendature," and joked to General John A. Rawlins, that they would be better off sending the Navajo to the "Fifth Avenue Hotel to board at the cost of the United States." By Sherman's own calculation, Bosque Redondo would cost the government some $2,002,277 between 1865 and 1868.[11]

Issues of the camp and the fate of those interred there was debated in Congress, and the Doolittle Committee was formed, led by Chairman of the Committee on Indian Affairs James Rood Doolittle, in order to in part investigate the squalid conditions and provide recommendations to Congress.[13][2] Eventually in 1867, Carleton was removed from command. The newly formed Indian Peace Commission, established to resolve the pressing issues of the western tribes, made their official report in January of the following year and recommended their course of action concerning the Navajo, that "a treaty be made with them, or their consent in some way [be] obtained, to remove at an early day to the southern district selected by us, where they may soon be made self- supporting."[11]

After negotiating the Second Treaty of Fort Laramie, peace commissioners William Tecumseh Sherman along with Samuel F. Tappan departed to treat with the Navajo and bring an end to their current arrangement.[11] There they met with Barboncito as tribal representative along with 10 headsmen.[14][15]

Negotiations

Sherman and Tappan arrived at Fort Sumner on May 28, 1868, with full authority granted by Congress earlier that year to negotiate a treaty.[10]: 464 The conditions on the reservation "deeply impressed Sherman" and "appalled Tappan". Tappan likened the plight of the Navajo to that of prisoners of war during the Civil War, imprisoned at Andersonville, Georgia, where conditions deteriorated so dramatically nearly 13,000 had died there.[11][16] In Sherman's words, "The Navajos had sunk into a condition of absolute poverty and despair."[11]

Initially, Sherman proposed moving the Navajo to the Indian Territory, in what would become the US state of Oklahoma. He offered to send a delegation there at the government's expense.[11] Barboncito refused, and the Navajo resolved that they would not plant again at Bosque Redondo.[6][11] Barboncito recited his grievances, according to one source:

the crowding together and dying of his people and their stock, their toil in vain, the cursed ground and the shame of going to the commissary for food, the grubbing of mesquite roots for fuel and carrying them on one's back for miles and miles, the Comanches' murderous raids."[11][d]

The Indian Bureau agent impressed upon the commissioners, that the Navajo were resolute that they should not remain at Bosque Redondo, and although they had remained peaceable thus far, "if not permitted to return to their own country, would leave anyway, committing depredations as they went."[11] Sherman telegraphed to Senator John B. Henderson, who had assumed the chair of the Indian Affairs Committee, advising him that "the Navajos were unalterably opposed to any resettlement in Texas, or any place further east, and would not remain at the Bosque Redondo without the use of overwhelming military force."[10]: 465

Tappan had been in favor of a return to their homeland from the outset, and Sherman relented, convinced that the land was unfit for white settlement, and that he had failed in his efforts to divert the Navajo elsewhere. What was left was to define the area to which they would return, and negotiations (through the double language barrier of translation from English to Spanish, and then from Spanish to Navajo) were not well understood. He agreed they could go outside the reservation to hunt and trade, but must make their homes and farms within its bounds, the area of which he overestimated by nearly double. A dozen miles south of the proposed reservation lay the surveyed route for planned rail construction along the 35th parallel, land which had been promised to the railroad for forty miles on either side.[11]

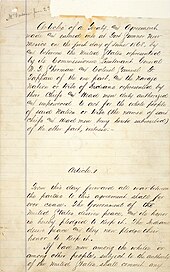

Signing

Ultimately, regardless of what may have been put down on the "white man's document", the Navajo thought "only of going home".[11] In total, 29 would make their mark, and the treaty was signed on June 1, 1868.[17]: 300 [18] It was ratified by the senate on June 24, 1868, and signed by President Andrew Johnson on August 12.[19]

Provisions

The treaty was divided into 13 articles. Much of the substance was modeled after the Treaty of Fort Laramie crafted for the Sioux earlier that year, and similar to many other such treaties, Bosque Redondo included a number of so-called civilization or assimilation provisions, designed to incentivize a transition to a landed agricultural existence.[20]: 75–6 [21]: 62 Provisions of the treaty included the following:

- The Navajo would stop all raiding, remain on the reservation in Arizona and New Mexico, and relinquish claims to land outside the reservation.[5]: 849 [22]: 193 The established reservation consisted of 3,500,000 acres (1,400,000 ha) on the border between New Mexico and Arizona, but excluded some of the best land for farming and grazing.[23]: 426

- The government would supply the Navajo with equipment for farming and seeds for planting. Each family would be allotted 160 acres (65 ha) of land.[5]: 849 [24]: 244 In all, the government agreed to provide 15,000 sheep and goats, and 500 head of cattle.[10]: 465

- The government agreed to pay $10 annually for 10 years to families engaged in "farming or mechanical pursuits" to be used by the commissioner Indian Affairs to purchase necessities.[17]: 300 Those who did not farm would receive $5 payments.[10]: 465

- For ten years the government would provide supplies for the reservation.[5]: 849 These were to be provided in the value of $100 for the first year, and $25 annually for the two years thereafter.[10]: 465

- The Navajo agreed to send their children aged six to 13 to attend school for a period of ten years, while the government agreed to provide one teacher per 30 students.[5]: 849 [10]: 465

- Those among the tribe who committed crimes would be subject to federal, rather than tribal law.[24]: 244

- The Navajo agreed not to interfere with railroad construction, or to harm any wagon trains or cattle.[2]

Aftermath and legacy

The signing of the treaty, as a treaty, and so defined by the US government as "an agreement between two nations", effectively established the sovereignty of the Navajo Nation, although still dependent on the federal government.[e] However, according to historian Jennifer Nez Denetdale, the treaty was also "the point at which the Navajo people lost their freedom and autonomy, and came under American colonial rule."[7] Denetale continues:

In affixing their X-marks to paper, Diné [Navajo] leader both affirmed Diné sovereignty and acknowledged the authority of the United States to limit tribal sovereignty. They did what they had to do in an impossible situation to allow their people to have a future.[25]

In their "Long Walk Home", the Navajo became a rare example in US history of native people successfully returning to their ancestral lands after being forcibly removed.[5]: 58 [9]: 364 Although in some respect the treated ended Carleton's Bosque Redondo experiment in failure, he had succeeded in ending the Navajo wars, nullifying the independence of the Navajo, and rendering them "wards of the government".[11]

On June 18, 1868, the group of 8,000, accompanied by some 2,000 sheep and 1,000 horses set off at a pace of 12 miles (19 km) per day.[26] The group arrived too late in the year to their homeland for the planting season, and were "forced to rely on rations, wild foods" and those Navajo who had avoided the long captivity at Bosque Redondo and had maintained their herds. The people would continue to struggle against their poverty for several years.[27]: 15

The land the newly established Navajo reservation was between 10% and 25% the size of their original lands, and did not include much of the best grazing land, much of which had been occupied by white settlers during the Navajo's internment at Bosque Redondo.[28]: 277–8 [3] The boundaries of the reservation remained nebulous, with as many as half living off the reservation by 1869, and even the army officers in the area were themselves unsure where the limits of the Navajo land may have been.[11] This proved advantageous for both parties. First for the Navajo, who enjoyed the greater freedom of movement allowed by lax enforcement, and also for the government, who could then claim the Navajo failed to respect their agreement, and abrogate their own obligations, saving tens of millions of dollars in subsidies.[11]

Of the benefits the government agreed to provide to the Navajo, none ever fully materialized.[28]: 278

Commemoration

June 1, 1868 is remembered among the Navajo as Treaty Day, and has since been commemorated, including on June 1, 1999, when thousands gathered at a ceremony held at Northern Arizona University.[21]: 323 In May 2018, one of two surviving original copies of the treaty was moved to the Navajo Nation Museum, for display as part of the 150th anniversary of the signing.[29] Ceremonies commemorating the 150th anniversary were also held at the Bosque Redondo Memorial, established in 2005, which includes a museum where the second surviving copy was displayed.[30][31]

See also

- Indian Appropriations Act – Legislation passed by the US government related to tribal lands

- List of United States treaties – Articles on treaties to which the US was a party

- Medicine Lodge Treaty – Negotiated by the Peace Commission with southern Plains Indian tribes in 1867

Notes

- ^ Literally, the old paper[3]

- ^ Hwéeldi in Navajo, literally the land of suffering[6][7]

- ^ Congress had originally appropriated only $100,000 for the Navajo. Half of this initial funding was lost to corruption, and within four month's time, the military managed to spend $510,000 to sustain Bosque Redondo.[11]

- ^ In reference to fuel, the land at Bosque Redondo had a notable shortage of available wood, according to the same source, which described the location as "an early treeless tract of sandy, gramagrass prairie".[11] For his part, Sherman described it as "a mere spot of green grass in the midst of a wild desert."[11]

- ^ See also Tribal sovereignty in the United States

References

- ^ a b "Up Heartbreak Hill". PBS. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d Ault, Alicia (February 22, 2018). "The Navajo Nation Treaty of 1868 Lives On at the American Indian Museum". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ a b Denedale, Jennifer Nez. "Naal Tsoos Saní (The Old Paper): The Navajo Treaty of 1868, Nation Building and Self-Determination". Native American Magazine. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ a b Schultz, Jeffrey D.; Aoki, Andrew L.; Haynie, Kerry L.; McCulloch, Anne M. (2000). Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics: Hispanic Americans and Native Americans. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-57356-149-5. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Newton-Matza, Mitchell (26 March 2014). Disasters and Tragic Events: An Encyclopedia of Catastrophes in American History [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-166-6. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ a b "The Treaty that Reversed a Removal—the Navajo Treaty of 1868—Goes on View". National Museum of the American Indian. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ a b Kate Nelson, Megan (May 22, 2018). "One of the 19th century's most important documents was recently discovered in a New England attic. Here's what it tells us". The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ a b Fredriksen, John C. (2001). America's Military Adversaries: From Colonial Times to the Present. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-603-3.

- ^ a b c Fixico, Donald L. (31 May 2018). Indian Treaties in the United States: A Encyclopedia and Documents Collection. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-6048-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Keleher, William A. (15 November 2007). Turmoil In New Mexico, 1846–1868: Facsimile of 1952 Edition. Sunstone Press. ISBN 978-1-61139-156-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Kessell, John L. (July 1981). "General Sherman and the Navajo Treaty of 1868: A Basic and Expedient Misunderstanding". The Western Historical Quarterly. 12 (3): 251–272. doi:10.2307/3556587. JSTOR 3556587.

- ^ Brewer-Wallin, Emma (2018). "We are lonesome for our land": The Settler Colonialist Use of Exodus in the Diné Long Walk". Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive: Honors Thesis Collection. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- ^ "The Treaty". The Bosque Redondo Memorial. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ "National Archives Confirm Authenticity of Third and Last-Remaining Copy of Treaty of Bosque Redondo". New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Hickman, Kennedy (May 16, 2016). "American Civil War: Andersonville Prison". ThoughtCo.com. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- ^ a b Heard, Joseph Norman (1987). Handbook of the American Frontier: The far west. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-3283-1. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ "President Begaye, Vice President Nez honor Navajo Nation Treaty Day" (PDF). The Navajo Nation. June 1, 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ "Navajo Treaty of 1868". University of Groningen. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Wilkins, David Eugene (2003). The Navajo Political Experience. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-2399-9.

- ^ a b Iverson, Peter (2002). Diné: A History of the Navajos. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-2715-4. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Weeks, Philip (16 February 2016). "Farewell, My Nation": American Indians and the United States in the Nineteenth Century. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-97678-4.

- ^ Fixico, Donald L. (12 December 2007). Treaties with American Indians: An Encyclopedia of Rights, Conflicts, and Sovereignty [3 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Rights, Conflicts, and Sovereignty. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-881-5. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ a b Brooks, Roy L. (June 1999). When Sorry Isn't Enough: The Controversy Over Apologies and Reparations for Human Injustice. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1331-0.

- ^ Harjo, Suzan Shown (30 September 2014). Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations. Smithsonian. ISBN 978-1-58834-479-3. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ Sundberg, Lawrence D. (1995). Dinétah: An Early History of the Navajo People. Sunstone Press. ISBN 978-0-86534-221-7. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Carnes, Mark C. (May 2005). American National Biography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-522202-9. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ a b Nies, Judith (1996). Native American History: A Chronology of the Vast Achievements of a Culture and Their Links to World Events. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-39350-0. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian Will Show Treaty Before It Travels to Navajo Nation Museum". Smithsonian Institution. February 2, 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ "Diné Commemorate 150th Anniversary of the Treaty of Bosque Redondo". Tribal College Journal of American Indian Higher Education. June 11, 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ Smith, Noel Lyn (January 14, 2018). "Summer events to commemorate Navajo-U.S. treaty". Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

External links

Works related to Treaty of Bosque Redondo at Wikisource

Works related to Treaty of Bosque Redondo at Wikisource- Proclamation from the Navajo Nation honoring the 150th anniversary of the treaty