Yan Tatsine

The Yan Tatsine was a militant Quranist[1][2] movement founded by the controversial Nigerian leader Maitatsine that first appeared around the early 1970s.

Activity

[edit]1980 events

[edit]The era of 1970-1980 witnessed the rise of Mohammed Marwa, a Cameroonian who inspired thousands to rise up against the existing political and religious order in Nigeria.[3] The group's mission under Maitatsine was the "purification" of Islam which, according to them, was corrupted by the West, and its modernization.[4]

As Maitatsine's support increased in the 1970s, so did the number of confrontations between Yan Tatsine and the police. By December 1980, continued Yan Tatsine attacks on other religious figures and police forced the Nigerian army to become involved. Subsequent armed clashes led to the deaths of around 5,000 people, including Maitatsine himself.[5] Maitatsine died shortly after sustaining injuries in the clashes either from his wounds or from a heart attack.[6]

Aftermath

[edit]When President Shehu Shagari called for all the foreigners to leave Nigeria, it created the worst international crisis since the end of the civil war in January 1970 and implemented a search of commercial, industrial and residential buildings to ensure their departure which caused tension with neighboring countries and international allies. The United States State Department described Nigeria's actions as "shocking and violation of every imaginable human right". The European Economic Community also criticized it and Pope John Paul II called it ""a grave, incredible drama producing the largest single, and worst human exodus in the 20th century". British politician Michael Foot sent a letter to the Nigerian High Commissioner in London, saying ""an act of heartlessness, and a failure of common humanity". British newspapers also commented with The Guardian saying it was "inhumanity, high-handedness and irresponsibility." South African politician P. W. Botha also criticized Shagari in the situation, comparing him to Adolf Hitler and other white right-wing groups said it was worse than apartheid in South Africa.[7]

French media such as the Jeune Afrique ran a front-page story "La Honte (The Shame)", saying the situation was "an act of barbarism unparalleled in the world" while Ghana newspaper Ghanaian Times said it was an "electoral gimmick" by the National Party of Nigeria-controlled government to deflect attention from its failures so it could win the 1983 election and also said the illegal alien expulsion was "create mass hysteria by infiltrating Sudan-trained mercenaries into Ghana to subvert the Ghanaian Government". Ghanaian politician Jerry Rawlings said it was a "calculated plot" against the Ghanaian government.[7]

Leadership after Maitatsine

[edit]Despite Mohammed Marwa's death, Yan Tatsine riots continued into the early 1980s. In October 1982 riots erupted in Bulumkuttu, near Maidaguri and in Kaduna, to where many Yan Tatsine adherents had moved after 1980. Over 3,000 people died. Some survivors of these altercations moved to Yola, and in early 1984 more violent uprisings occurred in that city. In this round of rioting, Musa Makaniki, a close disciple of Maitatsine, emerged as a leader and Marwa's successor.[5][6] Ultimately more than 1,000 people died in Yola and roughly half of the city's 60,000 inhabitants were left homeless. Makaniki fled to his hometown of Gombe, where more Yan Tatsine riots occurred in April 1985. A final riot occurred in Funtua, Kaduna state in 1987.[8] After the deaths of several hundred people Makaniki retreated to Cameroon, where he remained until 2004 when he was arrested in Nigeria,[9] where he was sentenced in 2006,[5] but later released.[10]

Despite the death of Mohammed Marwa, the work of Yan Tatsine has continued in modern times. Banned by the Nigerian government, they took refuge in Cameroon and then re-emerged in the limelight around 1995.[4] Their name changed to Sahaba.[4] Another leader of the Yan Tatsine, Malam Badamasi, was killed in 2009 after a series of armed insurrections,[11][12] while another had been arrested in connection with the killings of several members of the Sunni salafist group Boko Haram. Bomb-making tools and explosives, AK-47 rifles with several rounds of ammunition were recovered from the leader's home, according to the police, along with a number of swords, daggers and gunpowder.[13]

Some analysts view the terrorist group Boko Haram as an extension of the Maitatsine riots.[14]

In 2018, the Yan Tatsine group, alongside Boko Haram and Yan Hakika, was listed by Sunni Nigerian scholars as enemies of the Nigerian government, and the council of ulama urged the government under Buhari to provide security forces with adequate equipment.[15] The council called on the FG to establish a Religious advisory council so as to save the country from plunging into any religious war in the future.[15]

Ideology

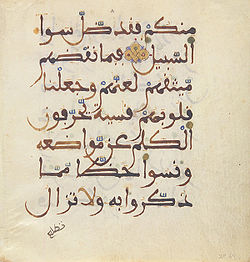

[edit]The Yan Tatsine movement was a militant Quranist movement which publicly adopted the slogan “Qur’an only” as the foundation of the religion.[16][17] They spoke against the Nigerian government, radios, watches, bicycles, cars and the possession of any money beyond trivial small sums.[18] The group prayed three times a day, arguing that the Qur'an mentions only three daily prayers and not five,[19] and used misbaha beads for supplication.[20][21]

Due to their excessive violence, the Yan Tatsine were considered the "grandmother of Boko Haram."[22]

Because the group was intensely suspicious of outsiders, and because their uprisings in the 1970s gave rise to many rumors and apocryphal stories, little reliable knowledge exists of the movement.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Fundamentalisms, Southworld.net

- ^ Loimeier, Roman (31 August 2011). Islamic Reform and Political Change in Northern Nigeria. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0-8101-2810-1.

- ^ Nwankwor, Emeka (9 December 2020). Buharism: Nigeria's Death Knell. FriesenPress. ISBN 978-1-5255-8324-7.

- ^ https://nationalinterest.org/feature/nigerias-boko-haram-horror-show-how-move-forward-10510. Archived 2019-02-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c "La vera storia di Boko Haram, dalla tentata purificazione dell'islam ai massacri quotidiani". 30 January 2015.

- ^ a b c J. Peter Pham, 19 Oct 06.In Nigeria False Prophets Are Real Problems, World Defense Review.

- ^ a b Hiskett, Mervyn (October 1987). "The Maitatsine Riots in Kano, 1980: An Assessment". Journal of Religion in Africa. 17 (3): 209–23. doi:10.1163/157006687x00145. JSTOR 1580875.

- ^ a b Abegunrin, Olayiwola (2003). Nigerian Foreign Policy Under Military Rule, 1966-1999. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 103. ISBN 0275978818. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ "Violence in metropolitan Kano: A Historical Perspective". Urban Violence in Africa : Pilot Studies (South Africa, Côte-d'Ivoire, Nigeria). African Dynamics. IFRA-Nigeria. 5 April 2013. pp. 111–136. ISBN 9791092312195.

- ^ KAYODE FASUA (Mar 3, 2013). Maitatsine: Tale of religious war in the North[usurped]. National Mirror Online.

- ^ Timawus Mathias. Musa Makaniki: Discharged and acquitted. Daily Trust, Wednesday, 09 May 2012 05:00.

- ^ "Beyond Islam In Nigeria". Catholic New Service of Nigeria. October 15, 2013.

- ^ Abiodun Alao, Islamic Radicalisation and Violence in Nigeria, Retrieved March 1, 2013

- ^ http://www.rfi.fr/actuen/articles/120/article_6332.asp. Archived 2018-06-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Johnson, Toni (31 August 2011). "Backgrounder: Boko Haram". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2011-09-01.

- ^ a b "Council of Ulama urges Buhari to provide police with adequate equipment". 7 November 2018.

- ^ Loimeier, Roman (31 August 2011). Islamic Reform and Political Change in Northern Nigeria. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0-8101-2810-1.

- ^ Nwankwor, Emeka (9 December 2020). Buharism: Nigeria's Death Knell. FriesenPress. ISBN 978-1-5255-8324-7.

- ^ Dr. Aliyu U. Tilde. "An in-house Survey into the Cultural Origins of Boko Haram Movement in Nigeria (Discourse 261)". MONDAY DISCOURSE WITH DR. ALIYU U. TILDE. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ^ Østebø, Terje (20 December 2021). Routledge Handbook of Islam in Africa. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-47172-4.

- ^ "Islamic Fundamentalism and Sectarian Violence: The Maitatsine and Boko Haram Crises in Northern Nigeria". docplayer.net.

- ^ Egbefo, Dawood (2015). "Terrorism in Nigeria: Its implication for Nation Building and National Integration" – via ResearchGate.

- ^ "Maitatsine: Story of Nigeria's bloody religious terror of the 80s". 4 November 2021.

- ^ "Mai Tatsine". 31 July 2014.