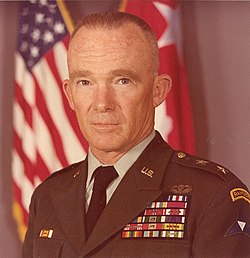

James L. Dozier

James Lee Dozier | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 10, 1931 Arcadia, Florida, U.S. |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1950–1985 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Deputy Chief of Staff at NATO's Southern European land forces |

| Battles / wars | Cold War |

| Awards | |

James Lee Dozier (born April 10, 1931) is a retired United States Army officer. In December 1981, he was kidnapped by the Italian Red Brigades Marxist guerilla group. He was rescued by NOCS, an Italian special force, with assistance from the Intelligence Support Activity's Operation Winter Harvest, after 42 days of captivity. General Dozier was the deputy Chief of Staff at NATO's Southern European land forces headquarters at Verona, Italy. The Red Brigades, in a statement to the press, stated the reason behind kidnapping an American general was that the U.S. and Italian governments had enjoyed excellent diplomatic relations and that Dozier was an American soldier invited to work in Italy, which justified their abduction. To date, Dozier is the only American flag officer to have been captured by a violent non-state actor.[1]

Military career

Dozier was born in Arcadia, Florida.[2] Dozier graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1956. He was a classmate of General Norman Schwarzkopf.[3] He went to the Armor School at Fort Knox, Kentucky, for basic and advanced training in armored warfare. He served in the Vietnam War with the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment from 1968 to 1969 [4] where he was awarded the Silver Star medal[5] and later served tours of duty at the Pentagon and in West Germany.

Education

Dozier graduated from the U.S. Military Academy with a Bachelor of Science degree in engineering. Later he earned a Master of Science degree in aerospace engineering from the University of Arizona. Dozier attended the Army Command and General Staff College and the Army War College.[6]

Kidnapping

Then–Brigadier General Dozier was kidnapped from his apartment in Verona at approximately 6 pm on December 17, 1981, by four men posing as plumbers. It was later reported that as many as four additional terrorists provided support with multiple vehicles. His wife, Judy Dozier, was not kidnapped, but was held at gunpoint briefly to coerce Dozier to comply and the terrorists left her bound and chained in the laundry room of their apartment.[7] Judy Dozier was rescued after she made noise by leaning against the washing machine and hitting it with her shoulders and knees, thereby getting the attention of a downstairs neighbor.[8]

In Paul J. Smith's (National Security Affairs professor at the U.S. Naval War College)[9] paper The Italian Red Brigades (1969–1984): Political Revolution and Threats to the State:

For more than a month, Dozier's right wrist and left ankle were chained to a steel cot, which was placed under a small tent. He was also forced to live under the "never-extinguished glare of an electric bulb." Dozier's captors also required him to wear earphones and listen to loud music. During Dozier's captivity, the Red Brigades issued various communiqués to the government and the public generally, describing their demands or complaints. They issued the first communiqué only days after the kidnapping; it was striking for its lack of any ransom demand. Instead it dwelled on international matters of interest to the Red Brigades, including a tribute to the German Red Army Faction. Subsequent communiqués also failed to mention ransom demands and even lacked any particular reference to Dozier. The fifth communiqué, retrieved from a trash can in downtown Rome, contained a number of anti-NATO and anti-American statements but did not make any specific demands for Dozier's release.[10]

Dozier was able to temporarily remove his headphones while his guard was not watching, allowing him to identify morning and evening traffic and thus tell time. He tracked the days in his diary, with a final count of 40, 2 days off from the true duration of his captivity. Dozier was able to keep a diary by playing Solitaire and writing down fake scores on paper provided by his guards. These scores were a base-seven alpha-numeric code developed by Dozier, based on the seven piles of cards used in the card game and the number of cards in each pile.[11]

The Red Brigades held Dozier for 42 days until January 28, 1982, when a team of NOCS (a special operations unit of the Italian police) successfully carried out his rescue from an apartment in Padua, without firing a shot, capturing the entire terrorist cell. The guard, Ugo Milani, assigned to kill Dozier in the event of a rescue attempt did not do so, and was overwhelmed by the rescuing force.

After Dozier's return to the U.S. Army in Vicenza, he was congratulated by telephone by President Reagan on regaining his freedom.[12]

Aftermath

Dozier was later promoted to major general and eventually retired from active military service.

Awards and decorations

This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (January 2018) |

During his military career he was awarded the Army Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star and Purple Heart (for actions during Vietnam War), Ranger Tab and Parachutist Badge.[13]

Ribbon bar

| |||

| Parachutist Badge | Ranger tab | |||||||||||||||||

| 1st row | Army Distinguished Service Medal | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd row | Silver Star | Defense Superior Service Medal | Legion of Merit | Bronze Star Medal w/ two OLCs and "V" Device | ||||||||||||||

| 3rd row | Purple Heart | Meritorious Service Medal w/ OLC | Air Medal w/ OLC | Army Commendation Medal w/ OLC | ||||||||||||||

| 4th row | Army Good Conduct Medal | National Defense Service Medal w/ service star | Vietnam Service Medal w/ four service stars | Vietnam Campaign Medal | ||||||||||||||

| Vietnam Gallantry Cross Unit Citation | ||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ^ BBC On This Day | 28 | 1982: US general rescued from Red Brigade. BBC News (1986-01-28). Retrieved on 2011-08-28.

- ^ "Man in the News; A Battle-hardened General". New York Times. 1982-01-29. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ^ "Retired Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf dies". NBC2. 2012-12-27. Archived from the original on 2017-08-12. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ^ "Man in the News; A Battle-hardened General". New York Times. 1982-01-29. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ^ "James L. Dozier". MilitaryTimes. Archived from the original on 2015-01-28. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ^ "Man in the News; A Battle-hardened General". New York Times. 1982-01-29. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ^ [1] Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dozier, James L. (2021). Finding My Pole Star. Front Edge Publishing. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-64180-112-6.

- ^ "U.S. Naval War College | Paul Smith". Archived from the original on 2013-01-19. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ^ Paul J. Smith. "The Italian Red Brigades (1969–1984): Political Revolution and Threats to the State".

- ^ Dozier, James L. (2021). Finding My Pole Star. Front Edge Publishing. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-64180-112-6.

- ^ Dozier, General James/Red Brigade Kidnapping Incident Archived 2007-03-29 at the Wayback Machine. Reagan.utexas.edu. Retrieved on 2011-08-28.

- ^ sptimes.com - Parade, service to honor veterans

Further reading

- Collin, Richard Oliver and Gordon L. Freedman. Winter of Fire, Dutton, 1990. ISBN 0-525-24880-3

- Dozier, James and Quelch, Douglas (Editor). Finding My Pole Star: Memoir of an American hero's life of faithful military service and as an active business and community leader, Front Edge, 2021. ISBN 978-1641801126

External links

- 1931 births

- 1980s missing person cases

- Formerly missing people

- Living people

- Kidnapped American people

- Missing person cases in Italy

- People from Fort Myers, Florida

- Recipients of the Air Medal

- Recipients of the Defense Superior Service Medal

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army)

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- Recipients of the Silver Star

- Red Brigades

- Terrorism in Italy

- United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni

- United States Army generals

- United States Army personnel of the Vietnam War

- United States Army War College alumni

- United States Military Academy alumni