Idris Bitlisi

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2011) |

Idris Bitlisi (c. 18 January 1457[1] – 15 November 1520), sometimes spelled Idris Bidlisi, Idris-i Bitlisi, or Idris-i Bidlisi ("Idris of Bitlis"), and fully Mevlana Hakimeddin İdris Mevlana Hüsameddin Ali-ül Bitlisi, was an Ottoman Kurdish religious scholar and administrator.

Even though many scholarly works mention Bitlis as Bitlisi's place of birth, a new research states that he was actually born in the district of Sulaqan in Ray in northern Iran.[1]

He wrote a major Ottoman literary work in Persian, named Hasht Bihisht, which began in 1502 and covered the reign of the first eight Ottoman rulers.[2]

Biography

Bitlisi's father, Hosam al-Din Ali Bitlisi, was a Sufi author strongly affiliated with the Sufi Nurbakhshi sect.[3] Like his father, Idris Bitlisi began his career in the Aq Qoyunlu court, in the service of Yakup Bey, son of Uzun Hasan. He attracted the attention of the Ottoman sultan Selim I and served under him for much of the rest of his life. He joined Selim I in his campaigns against the Mamluks and the Safavids. In 1514 he led the Kurdish forces who captured Diyarbakır from the Safavids.[4] Following the success of the military campaign led by him, he was able to form an alliance between the Kurdish notables and the Ottoman Empire. Selim I entrusted Bitlisi to persuade the Kurds to maintain the alliance between the Kurdish notables and the Ottoman Empire by delivering him with an exceptional authority to deposit territories to the Kurdish notables within the Ottoman Empire to govern over them with an extended autonomy.[5] Bitlisi also assisted the sultan in establishing an Ottoman administration in Egypt, now the Egypt Eyalet (province) of the Ottoman Empire, after its conquest in 1517. He was appointed to numerous administrative positions of significant responsibility including Kazasker (district supreme administrative judge) of Diyarbekir and Arabia.

Bitlisi was instrumental in the incorporation of the territories of Urfa and Mosul into the Ottoman Empire without a war, and of Mardin after a long siege. He played a key role in driving the Alevi Turkomans from the whole region and the assimilation and Ottomanization of the remaining Sunni Kurds.

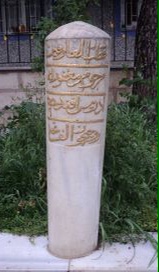

He died in Constantinople on 15 November 1520, shortly after the death of his longtime benefactor, Sultan Selim I. Bitlisi was buried in Eyüp neighborhood of Constantinople, in the garden of the complex known as "İdris Köşkü" (Idris House) or "İdris Çeşmesi" (Idris Fountain), built by his wife Zeynep Hatun.

Bitlisi wrote extensively towards the end of his life; his best known work is "Selim Şahname", an epic history of Selim I's reign.

Hasht Bihisht

Bitlisi's Persian Hasht Bihist (also spelled Hasht Behest or Heşt Behişt) was written making explicit use of the stylistic and organizational models of Persianate historiography.[6] Most of the work's content derives best-known written by earlier Ottoman chroniclers.[6]

References

- ^ a b Genç, Vural (2019). "Rethinking Idris-i Bidlisi: An Iranian Bureaucrat and Historian between the Shah and the Sultan". Iranian Studies. 52 (3–4): 427. doi:10.1080/00210862.2019.1649979. S2CID 204479807.

- ^ Bertold Spuler. Persian Historiography & Geography Pustaka Nasional Pte Ltd ISBN 9971774887 p 68

- ^ Yazici 2004, p. 490.

- ^ Özoğlu, Hakan (2004-02-12). Kurdish Notables and the Ottoman State: Evolving Identities, Competing Loyalties, and Shifting Boundaries. SUNY Press. pp. 47–49. ISBN 978-0-7914-5993-5.

- ^ Klein, Janet (2011-05-31). The Margins of Empire: Kurdish Militias in the Ottoman Tribal Zone. Stanford University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-8047-7570-0.

- ^ a b Hagen, Gottfried (2013). "The order of knowledge, the knowledge of order: Intellectual life". In Faroqhi, Suraiya N.; Fleet, Kate (eds.). The Cambridge History of Turkey: Volume 2, The Ottoman Empire as a World Power, 1453–1603. Cambridge University Press. p. 448. ISBN 978-0-521-62094-9.

Bibliography

- Uğur, Ahmet (1991). İdris-i Bitlisi ve Şükri-i Bitlisi (in Turkish). Kayseri, Turkey: Erciyes Üniversitesi Yayınları. ISBN 978-975-7598-17-6.

- Bayraktar, Mehmet (2006). Kutlu Müderris İdris-i Bitlisi (in Turkish). Istanbul, Turkey: Biyografi Net Yayınları. ISBN 978-975-00394-7-8.

- Kirlangic, Hicabi (2001). Selim Şahname (in Turkish). Ankara, Turkey: Works on Culture Series, Turkish Ministry of Culture. ISBN 975-17-2588-7.

- Yazici, Tahsin (2004). "ḤOSĀM-AL-DIN ʿALI BEDLISI". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5. p. 490.

Further reading

- Dehqan, Mustafa (2024). "From Historian to Poet: A Checklist of the Persian Poems of Idrīs Bidlīsī (Hašt Bihišt VI, Nuruosmaniye 3209)". DABIR. 10: 49–60. doi:10.1163/29497833-20230011.

- Genç, Vural (2019). "Rethinking Idris-i Bidlisi: An Iranian Bureaucrat and Historian between the Shah and the Sultan". Iranian Studies. 52 (3–4): 425–447. doi:10.1080/00210862.2019.1649979. S2CID 204479807.

- Genç, Vural (2021). "An Iranian Shāh-nāma Writer at the Court of Bāyezid II: Malekzāda Āhi". Journal of Persianate Studies. 13 (2): 119–145. doi:10.1163/18747167-bja10009. S2CID 237805512.

- Markiewicz, Christopher (2019). The Crisis of Kingship in Late Medieval Islam: Persian Emigres and the Making of Ottoman Sovereignty. Cambridge University Press.

- People from Ray, Iran

- People from Bitlis

- Jurists from the Ottoman Empire

- Civil servants from the Ottoman Empire

- Political people from the Ottoman Empire

- Kurdish people from the Ottoman Empire

- 1457 births

- 1520 deaths

- Kurdish scholars

- Kurdish theologians

- 16th-century Persian-language writers

- Scholars under the Aq Qoyunlu

- Officials under the Aq Qoyunlu

- 15th-century Kurdish people

- 16th-century Kurdish people

- Kurdish Muslims