Saint-Jacques-du-Haut-Pas

| Church of Saint-Jacques du Haut-Pas | |

|---|---|

Église Saint-Jacques du Haut-Pas | |

| |

| 48°50′37″N 2°20′29″E / 48.84361°N 2.34139°E | |

| Location | Île-de-France, Paris |

| Country | France |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic Church |

| Website | www |

| History | |

| Status | Parish church |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural type | church |

| Style | Gothic and French Baroque architecture |

| Groundbreaking | 16th century |

| Completed | 17th century |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | Archdiocese of Paris |

Saint-Jacques du Haut-Pas (French pronunciation: [sɛ̃ ʒak dy o pɑ]) is a Roman Catholic parish church in Paris, France. The church is located at the corner of Rue Saint-Jacques and Rue de l'Abbé de l'Épée in the 5th arrondissement of Paris. The first church on the site, a monastery chapel, was built in 1360. The present church was completed in 1685.[1] The church is named for Saint-Jacques Du-Haut-Pas," (in English Saint James the Minor), a cousin of Christ and the first bishop of Jerusalem, who was martyred in the year 60. It was registered as an historical monument on 4 June 1957.[2]

History

Hospital and chapel

The land on which the hospital and chapel were built, at the time outside the city walls, was obtained around 1180 by the Order of the Holy Ghost, a community of Italian monks from Tuscany, who built hospitals and provided medical care for the poor and to pilgrims; the route of the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela Cathedral passed close to the hospital.

In 1360 they built a larger new hospital and chapel on the site. The Order was abolished by Pius II in 1459, but some of the monks remained to keep the hospital open.[3]

In 1572 the Queen of France, Catherine de' Medici gave the hospital and its chapel to a community Benedictine monks who have had been expelled from their abbey of Saint-Magloire. The relics of St. Magloire of Dol and his disciples had been transported to Paris by Hugh Capet in 923, These relics were transferred to the monastery. The reliquary is displayed in the church, while the relics are kept at a more secure site.[4]

The new church (1584)

The population of the neighbourhood grew quickly and growing numbers became accustomed to praying in the chapel of the Benedictines. The monks asked that a separate church be constructed for them.[5] In 1582 the bishop gave permission for construction of new parish church adjoining the monastery. Financing was provided by Monsieur, the brother of the King, and by the Duchess of Longueville. The choir of the new church faced east, backing onto rue Saint-Jacques.[6] A cemetery was opened in 1584 beside the original chapel, along today's rue de l’Abbé-de-l’Épée. It was closed in 1790.[7]

In 1618 the Old monastery became the site of the first seminary in Paris, the Oratorians under Pierre de Bérulle, It was called the seminary of Saint-Magloire. The celebrated poet and fable-writer Jean de La Fontaine briefly attended the seminary. His experience convinced him to abandon becoming a monk and to become an author instead.[8]

Enlargements and modifications

As the population of the neighbourhood grew rapidly, the church soon needed to be enlarged. In 1630 Gaston, Duke of Orléans, brother of Louis XIII, donated funds to start the enlargement of the church. They planned a new choir in the Flamboyant Gothic style beside the original entrance. When funding ran short, the workers donated their services one day a week without pay.[9]

In 1675 the church underwent another major reconstruction, directed by architect Daniel Gittard, who had designed the ornate choir of the Church of Saint-Sulpice. The old nave was demolished and reconstructed, and a new facade was built on Rue Saint-Jacques. Gittard had originally planned two towers for the facade, but only one was built, though it was made twice as high as originally planned. The church was re-consecrated on May 6, 1685.[10]

A final major addition was made in 1687, with the construction of a new Chapel of the Virgin. It was designed by Liberal Bruant, whose major works included the Les Invalides.

Jansenism and the church

In the 17th century the church played an important role in the development of the theological doctrine called Jansenism, which called for a more austere way of living, and differed significantly from the official theology of the Roman Catholic Church. The church contains the tomb of Jean du Vergier de Hauranne (1581–1643), the abbot of Saint-Cyran, a theologian who was a friend of Cornelius Jansen and was responsible for the spread of Jansenism in France.[7] His tomb became a major pilgrimage destination for the followers of the doctrine, though the doctrine was officially condemned by the Roman Catholic Church.

Jean-Denis Cochin and his hospital

Jean-Denis Cochin (1726–1783) was the parish priest from 1756 to 1780. He created devotional works, but his main occupation was to help disadvantaged people.[7] He founded a hospital to receive indigent patients, for which he laid the foundation stone on 25 September 1780 in the Faubourg Saint-Jacques. He named it after the parish patrons, Hôpital Saint-Jacques-Saint-Philippe-du-Haut-Pas.[11] The hospital treated injuries suffered by poor workers, most of whom worked in the nearby quarries. Jean-Denis Cochin was buried at the foot of the chancel of the church.[7] In 1802 the hospital was given the name of its founder: Hôpital Cochin.[11]

French Revolution

During the French Revolution, the church was closed and valuables pillaged. However, in 1793, it was one of the fifteen Catholic churches in Paris which were allowed to re-open. A new pastor, Vincent Duval, was elected by the residents of the Parish. At the same time, other religions were permitted to use the church for their own services. The nave was used by the Roman Catholic Church, while the use of the choir was granted to the followers of a new religion called of Theophilanthropy. Their portion of the church in the choir was called the "Temple of Charity." After the Concordat of 1801 proposed by Napoleon, the Catholic Church regained exclusive use of the entire building.[12]

19th and 20th centuries

The building had been simply and sparsely decorated due to the influence of Jansenism. In the nineteenth century, mainly during the July Monarchy and under the Second Empire, it was considerably embellished. Many paintings and stained glass windows were offered by wealthy families such as the Baudicour family, who in 1835 provided the altar located in the north aisle and the entire decoration of the chapel of Saint-Pierre. Auguste Barthelemy Glaize, a student of Achille and Eugène Devéria, redecorated the chapel of the Virgin in 1868.

In 1871 an explosion of the Luxembourg powder magazine caused major damage to the organ. It was not until 1906 that it was restored, with innovative electro-pneumatic components. These gradually deteriorated, and another major restoration was undertaken in the 1960s by Alfred Kern & fils. The new organ, which retains parts of the old, was inaugurated on 18 May 1971 by Pierre Cochereau.[13] Following the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), the interior space was rearranged. An altar, cross and a pulpit by the sculptor Léon Zack were placed in the transept.[14]

Charles de Sévigné (1648-1713), son of the famous Marie de Rabutin-Chantal, marquise de Sévigné, is buried here. After living very gallantly as a young man, he later turned to the austere life of the Jansenists. The Italian/French astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini (1625–1712) and the French mathematician and astronomer Philippe de La Hire (1640–1718) were also buried here.[7] The funeral of the French mathematical physicist Henri Poincaré on 19 July 1912 took place in this church.

The Church interior was also renovated in the 20th century, following the Second Vatican Council, most notably with the total removal of the historic high altar. The current main altar now a simplistic table in the crossing of the Church, on a temporary carpeted platform. The furnishings typical of the choir in a French Church such as this were also completely removed, leaving the building lacking the clear architectural focus that the original altar arrangement had.

Exterior

-

Tower and Facade

-

Portal with fronton and three rose windows

The exterior of the church is austere and rigorous, influenced by the philosophy of the Jansenists. The facade has a portal in the classic style, with a fronton supported by four classical columns, while the tower, rose windows and buttresses are inspired by Gothic architecture. The church was originally planned to have two towers, but for financial reasons the plan was modified to one higher tower. The facade was completed its present form in 1684.[15]

Interior

-

Nave and the pulpit

-

Chapel of the Virgin

-

Altar and choir

The interior, ike the exterior, is austere and has a minimum of decoration, The nave has arcades with rounded arches supported by cruciform pillars and decorated with pilasters dtopped with classical pediments. The architecture is brightened by a collection of paintings and colorful stained glass windows, and the interior is filled with light from the white glass of the large upper windows.[16]

The choir is very long, and is sometimes called "The Little Nave". The Chapel of the Virgin in the apse is visible at the back of the choir. The altar in the transept is a modern work, designed by Léon Zack (1971). It consists of an oak chest topped by a table of rose-colored marble.[17]

The Chapel of the Virgin is located in the apse, directly behind he choir, and is visible from the nave. It was the last part ion the church built, and the most ornate.

Notable parishioners

The tomb of the Italian-born French astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini (1625-1712) is found in the church. He was the first director of the Paris observatory from 1671 to his death in 1711, the first to discover four moons off Saturn and the separation of the rings of Saturn, and the first to calculate the distance between the Earth and Sun, among many other discoveries. He was court astronomer and astrologer to King Louis XIV, and made the first accurate measurement of the size of France, which turned out to be much smaller than Louis XIV expected.[18]

Édouard Branly, the inventor of wireless telegraphy, was a long-time member of the congregation.

The Organ

-

The organ in the tribune.

The original gallery organ was made by Vincent Coupeau, an organist of the parish, and was installed in 1628.[13] The original organ was replaced by other instruments, including one that the Abbé Courcaut, the parish priest, installed himself in 1733. A larger organ made by François Thierry was installed in 1742. After the Saint-Benoît-le-Bétourné Collegiate[a] its organ was transferred and installed by Claude-François Clicquot. This organ was made by Matthijs Langhedul. Part of the wooden buffet had been made by Claude Delaistre in 1587, so the church has part of the oldest organ case in Paris.[13]

Art and Decoration

While the architecture of the church is rather austere, in the Jansenist style, the interior is decorated with a large number of paintings and sculpture, carved wood decoration in the organ case and pulpit, and colorful 19th-century stained glass.

Stained glass

-

Stained glass window depicting the Last Supper

-

Detail- Christ at the Last Supper

-

North side window; Christ and Saint Peter

-

Central widow above choir; the Apostles

-

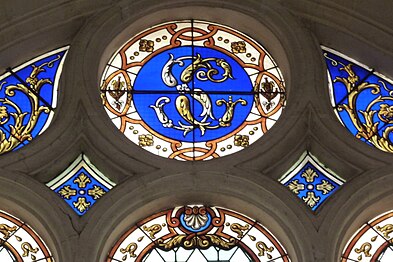

Window detail - a monogram

-

Many of the top windows are largely white glass, to admit a maximum of light

Painting and sculpture

The early church was a stopping point on the Pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. One of the oldest works in the church, found in the disambulatory, is statue of Saint James the Great, one of the first disciples and martyrs, depicting him a pilgrim, holding a copy of the scripture.[19]

-The most prominent work of sculpture is the statue of the Virgin Mary and child, crushing a serpent, which is the center of the Chapel of the Virgin. (19th century) [20]

-

Saint James the Great depicted as a pilgrim (15th century).

-

"Virgin and Child, Crushing a serpent" (19th c.)

-

Ceiling of the Chapel of the Virgin,"Angels carrying the litanies of the Virgin" by Auguste-Barthelemy Glaize (1868).

-

Magloire, a 6th-century Breton saint, oil painting by Eugène Goyet (1798–1846)

-

Bas-relief in cherry wood: "The Virgin appearing to Saint James", School of Auvergne (17th century)

-

Ceiling of the chapel of the Virgin representing the Holy Trinity

-

Reliquary of Saint Magloire, a Breton saint. The relics have been moved to another location.

-

Plaque on the façade of the church stating that it is on the road to Saint Jacques de Compostela

-

The wireless telegraphy pioneer Édouard Branly was a member of the parish

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ Dumoulin, "Eglise de Paris" (2017) pp. 92-93

- ^ Eglise Saint-Jacques-du-Haut-Pas – Mérimée.

- ^ Dumoulin, "Églises de Paris" (2017), p. 92

- ^ Dumoulin, "Églises de Paris" (2017), p. 92

- ^ [1]|"History" section of church website

- ^ [2]|"History" section of church website

- ^ a b c d e Landru 2008.

- ^ Dumoulin, "Églises de Paris" (2017), p. 92

- ^ [3]|"History" section of church website

- ^ Dumoulin, "Églises de Paris" (2017), p. 93

- ^ a b Historique de l'hôpital COCHIN.

- ^ "Article in patrimoine-histoire.fr on the history and art of the church (in French)".

- ^ a b c Orgues de l'église Saint-Jacques-du-Haut-Pas.

- ^ Historique.

- ^ Dumoulin, Églises de Paris" (2017), p. 92

- ^ Dumoulin, Églises de Paris" (2017), p. 92

- ^ "Article in patrimoine-histoire.fr on the history and art of the church (in French)".

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Gian Domenico Cassini", retrieved May 21, 2023

- ^ Dumoulin, "Églises de Paris" (2017), p. 92

- ^ Dumoulin, "Églises de Paris" (2017), p. 92

Bibliography

Sources and External Links

- "Eglise Saint-Jacques-du-Haut-Pas". base Mérimée. ministère français de la Culture. Retrieved 2012-11-20.

- "History in the Church website (In French)". Église Saint-Jacques-du-Haut-Pas. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- "Historique de l'hôpital COCHIN". Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris. Retrieved 2012-11-20.

- Landru, Philippe (7 February 2008). "église ST-JACQUES-DU-HAUT-PAS". Cimetières de France et d’ailleurs. Retrieved 2012-11-21.

- "Orgues de l'église Saint-Jacques-du-Haut-Pas". Université du Québec à Montréal. Retrieved 2012-11-21.