Battle of Montaperti

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Italian. (September 2012) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Battle of Montaperti | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the conflict between the Guelphs and Ghibellines | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Ghibellines:[1][2] Siena Manfred of Sicily Pisa Terni Florentine exiles |

Guelphs:[1][2] Florence Lucca Bologna Prato Orvieto San Gimignano San Miniato Volterra Colle Val d'Elsa | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Provenzano Salvani Farinata degli Uberti Giordano d'Anglano Ildebrandino Aldobrandeschi [5][6][7] |

Jacopino Rangoni † Niccolò Garzoni † [5][6][7] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 17,000 troops[5][6][8] | 33,000 troops[1][5][6] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

600 killed[9] 400 wounded[9] |

2,500 killed[1][6][10] 1,500 captured[1][6][10] | ||||||

The Battle of Montaperti was fought on 4 September 1260 between Florence and Siena in Tuscany as part of the conflict between the Guelphs and Ghibellines. The Florentines were routed. It was the bloodiest battle fought in Medieval Italy, with more than 10,000 fatalities. An act of treachery during the battle is recorded by Dante Alighieri in the Inferno section of the Divine Comedy.

Prelude

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2019) |

The Guelphs and Ghibellines were rival factions that nominally sided with the Papacy or the Holy Roman Empire, respectively, in Italy in the 12th and 13th centuries.[11]

In the mid-13th century, Guelphs held sway in Florence whilst Ghibellines controlled Siena. In 1258, the Guelphs succeeded in expelling from Florence the last of the Ghibellines with any real power;[12] they followed this with the murder of Tesauro Beccharia, Abbot of Vallombrosa, who was accused of plotting the return of the Ghibellines.[13]

The feud came to a head two years later when the Florentines, aided by their Tuscan allies (Bologna, Prato, Lucca, Orvieto, San Gimignano, San Miniato, Volterra, and Colle Val d'Elsa), moved an army of some 35,000 men (including 12 generals) toward Siena.[14] The Sienese called for help from King Manfred of Sicily, who provided a contingent of German mercenary heavy cavalry, as well as the Holy Roman states of Pisa and Cortona.[14] The Sienese forces were led by Farinata degli Uberti, an exiled Florentine Ghibelline. Even with these reinforcements, though, they could only raise an army of less than 20,000.

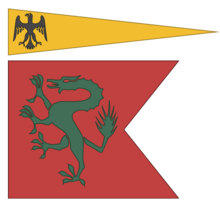

The battle

The Ghibelline army consisted of four divisions,[15] with a well worked out but risky plan involving an ambushing force in the rear of the Florentine army. The first division, led by Count d'Arras, the seneschal of Count Giordano (the German mercenary commander), consisted of 200 German knights and 200 Sienese crossbowmen,[16] who maneuvered unseen south of the battlefield around the Monselvoli-Costaberci Ridge and took up a position south of Monselvoli Hill along the road to Asciano with orders to charge the Guelfs upon hearing the Ghibellines shout “San Giorgio" ("Saint George").[17] The second division, led by the German commander, Count Giordano d'Agliano made up the vanguard of the Sienese main body and consisted of 600 German knights and 600 infantry.[16] The third division, led by the captain of the Sienese forces, Count Aldobrandino Aldobrandeschi, formed the main body of the Ghibelline army, consisting of about 600 Tuscan knights and 17,000 Sienese and allied infantry. The fourth division, commanded by Niccolò da Bigozzi, centurion of the Terzo di Camollia, made up the rearguard with the specific task of guarding the Sienese carroccio, and consisted of 200 Sienese knights and a few hundred armed priests and monks.[16] At least, from Umbria, there was the most historical and fiercer Ghibelline city-state: Terni (rewarded by a little more than two decades by Frederick II with the black eagle in a gold field in its national banner: "... for the loyalty and vigor of his men ... "and commanded by an old, solid and proud aristocracy of Germanic lineage: House of Castelli in the first place, a family descendant from the Frankish princes of Terni, but also the Houses of Camporeali and Cittadini). According to Sienese tradition, the day before the battle, the Ghibelline army marched thrice around the Ropole Hill in full view of the Guelf army, changing uniforms each time and mounting non-combatants on pack animals in order to create the impression that their army was three times as large as it actually was.[18] In addition, the Ghibellines conducted harassing night raids on the Guelf camp. The result sowed caution in the Florentine commanders, who decided on a strategic withdrawal and had begun to break camp when the Sienese army crossed the Arbia River, probably on a bridge at Taverne d'Arbia early on 4 September, and began advancing. The Florentines had no choice but to offer battle.[citation needed]

The battle took place at the foot of the Monselvoli-Costaberci Ridge about six kilometers east of Siena. The Ghibelline-Sienese army was arrayed north to south with the vanguard (German knights) on the north, or left wing, and the main body stretched out to the south. To the east, facing them, with the tactical advantages of being uphill and with a rising sun behind them were the Guelf-Florentines, in a defensive posture.[16] The precise organization of the Guelf army is not known but it is nearly certain that they positioned their main body of infantry (some 30,000) on the south opposite the Sienese infantry with their cavalry (some 3,000 knights) on the north facing the German and Tuscan knights.[16]

The Sienese-Ghibelline army waited until the sun was well up in order to deny that advantage to the enemy, and the battle finally started around 10:00 with a charge of the German knights, which forced the right wing of the Guelfs to withdraw.[17] The Tuscan knights of the Ghibelline third division entered the melee, and while the knights were thus engaged on the north end of the battlefield, the Sienese and allied infantry attacked the Florentines on the steepest side of Monselvoli. The battle raged with the Florentines gradually gaining the upper hand due to the weight of superior numbers until about 15:00, when Niccolò da Bigozzi (in command of the Sienese 4th Division) attacked and stabilized the situation.[17] At about this same time, a group of Tuscan Ghibelline exiles, who were fighting in the Sienese-Ghibelline army, convinced some relatives fighting on the opposite side to betray the Guelfs. A knight with Ghibelline sympathies, but fighting with the Florentines (Bocca degli Abati), joined the Sienese cause by charging the standard-bearer of the Florentine cavalry and cutting off the hand that held the Florentine battle flag. Bocca and the other Ghibelline sympathizers in the Guelph ranks then charged the Florentine carroccio, but without success.[17]

By then it was late in the day and the Guelphs had the sun in their eyes. Around 18:00, the prearranged cry of “San Giorgio” went up from the Ghibelline ranks, and Count Arras led his German knights from ambush directly against the Florentine commander (who was probably Iacopino Rangoni da Modena, Uberto Ghibellino or Buonconte Monaldeschi – the chronicles differ)[16] and killed him. This led to the beginning of a rout of the Florentine-Guelph forces. The greater part of the Florentine cavalry was destroyed, their camp sacked, and their carroccio was captured.[19] It is estimated that 10,000 men died on the Guelph side, 4,000 went missing, and 15,000 were captured, the rest running for their lives.[14] Some 600 Ghibelline soldiers died.[20]

After the battle, the German soldiers in the Sienese army used part of their pay to found the Church of San Giorgio in via Pantaneto—the Germans had called on Saint George as their battle-cry during the fight.[21]

Depiction in the Divine Comedy

Dante studied under Florence's Chancellor Brunetto Latini, who was himself away from the battle scene, on embassy in Castile seeking help for Guelph Florence from Alfonso X el Sabio. Dante would have learned of the battle, its preparations (documented by Latini in the Libro di Montaperti), strategies and treachery, as well as those of the Battles of Benevento and Tagliacozzo, from the Chancellor,[22] using material also to be gleaned later by Giovanni Villani, the Florentine merchant and historian. As a result, Dante reserved a place in the ninth circle of Hell for the traitor Bocca degli Abati in his Divine Comedy. The Ghibelline commander Farinata degli Uberti is also consigned to Dante's hell, not for his conduct in the battle, but for his alleged heretical adherence to the philosophy of Epicurus.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Leo, Heinrich (1830). Geschichte der italienischen Staaten: Vom Jahre 1268–1492. Hamburg.

- ^ a b Brockhaus (1838). Blätter für literarische Unterhaltung: Vol. 2. Leipzig.

- ^ a b Gebrüder Reichenbach (1841). Allgemeines deutsches Conversations-Lexicon: Vol. 10. Leipzig.

- ^ Kopisch, August (1842). Die Göttliche komödie des Dante Alighieri. Berlin.

- ^ a b c d Busk, Mrs. William (1856). Mediæval popes, emperors, kings, and crusaders: Vol. 4. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f von Raumer, Friedrich (1824). Geschichte der Hohenstaufen und ihrer Zeit: Vol. 4. Leipzig.

- ^ a b Damberger, Joseph Ferdinand (1857). Synchronistische Geschichte der Kirche und der Welt im Mittelalter: Vol. 10. Regensburg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lau, Dr. Thaddäus (1856). Der Untergang der Hohenstaufen. Hamburg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Villari, Pasquale (1905). I primi due secoli della storia di Firenze. Florence.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Trollope, Thomas Adolphus (1865). A history of the commonwealth of Florence: Vol. 1. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hathaway 2015, p. 59.

- ^ Nicholas 2014, pp. 268–269.

- ^ Holloway 1993, p. 203.

- ^ a b c Picone-Chiodo 2006.

- ^ Marchionni, Roberto. Sienese's Battles (1) Montaperti. Siena: Roberto Marchionni Editore, 1996.

- ^ a b c d e f Marchionni, 41.

- ^ a b c d Marchionni, 43.

- ^ Marchionni, 40.

- ^ Marchionni, 44.

- ^ Marchionni, 45.

- ^ Parsons, Gerald (2004), Siena, Civil Religion, and the Sienese, Burlington, VT: Ashgate Press, p. 21, ISBN 0-7546-1516-2.

- ^ Julia Bolton Holloway, Twice-Told Tales: Brunetto Latino and Dante Alighieri

Sources

- Hathaway, Jane (2015). "A Mediterranean Culture of Factions? Bilateral Factionalism in the Greater Mediterranean Region in the Pre-Monder Era". In Piterberg, Gabriel; Ruiz, Teofilo; Symcox, Geoffrey (eds.). Braudel Revisited: The Mediterranean World 1600-1800. University of Toronto Press.

- Holloway, Julia Bolton (1993). Twice-told Tales: Brunetto Latino and Dante Alighieri. Peter Lang.

- Nicholas, David M (2014). The Growth of the Medieval City: From Late Antiquity to the Early Fourteenth Century. Routledge.

- Picone-Chiodo, Marco (2006). "Battle of Montaperti: 13th Century Violence on the Italian 'Hill of Death'". Military History Magazine. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

External links

- 1260 in Europe

- 1260s in the Holy Roman Empire

- Conflicts in 1260

- Battles involving the Republic of Florence

- Battles involving the Republic of Siena

- Military history of Tuscany

- Wars of the Guelphs and Ghibellines

- 13th century in the Republic of Florence

- 13th century in the Republic of Siena

- Castelnuovo Berardenga