Inductive coupling

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2009) |

In electrical engineering, two conductors are said to be inductively coupled or magnetically coupled[1] when they are configured in a way such that change in current through one wire induces a voltage across the ends of the other wire through electromagnetic induction. A changing current through the first wire creates a changing magnetic field around it by Ampere's circuital law. The changing magnetic field induces an electromotive force (EMF) voltage in the second wire by Faraday's law of induction. The amount of inductive coupling between two conductors is measured by their mutual inductance.

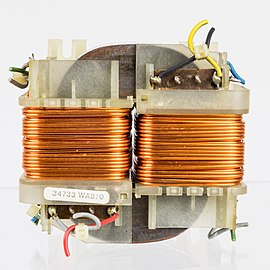

The coupling between two wires can be increased by winding them into coils and placing them close together on a common axis, so the magnetic field of one coil passes through the other coil. Coupling can also be increased by a magnetic core of a ferromagnetic material like iron or ferrite in the coils, which increases the magnetic flux. The two coils may be physically contained in a single unit, as in the primary and secondary windings of a transformer, or may be separated. Coupling may be intentional or unintentional. Unintentional inductive coupling can cause signals from one circuit to be induced into a nearby circuit, this is called cross-talk, and is a form of electromagnetic interference.

An inductively coupled transponder consists of a solid state transceiver chip connected to a large coil that functions as an antenna. When brought within the oscillating magnetic field of a reader unit, the transceiver is powered up by energy inductively coupled into its antenna and transfers data back to the reader unit inductively.

Magnetic coupling between two magnets can also be used to mechanically transfer power without contact, as in the magnetic gear.[2]

Uses

Inductive coupling is widely used throughout electrical technology; examples include:

- Electric motors and generators

- Inductive charging products

- Induction cookers and induction heating systems

- Induction loop communication systems

- Metal detectors

- Transformers

- Wireless power transfer

- Testing:

- Radio-frequency identification

- Presence of voltage

- Uses of inductive coupling

-

Power transformer transfers power from one winding to the other by inductive coupling

-

Antenna transformer inductively couples antenna of AM radio station to transmitter

-

clamp ammeter measuring current by inductive coupling

-

Utility transformer cutaway shows inductively coupled coils

-

Variometer from radio allows inductive coupling to be varied

-

Ignition coil of truck produces high spark plug voltage by inductive coupling

-

Inductive charger wirelessly charging a cellphone

-

Prototype railgun accelerates a projectile by inductive coupling

-

Induction furnace heats silicon by eddy currents

-

Induction stove boiling water by inductive coupling to pan

Low-frequency induction

Low-frequency induction can be a dangerous form of inductive coupling when it happens inadvertently. For example, if a long-distance metal pipeline is installed along a right of way in parallel with a high-voltage power line, the power line can induce current on the pipe. Since the pipe is a conductor, insulated by its protective coating from the earth, it acts as a secondary winding for a long, drawn out transformer whose primary winding is the power line. Voltages induced on the pipe are then a hazard to people operating valves or otherwise touching metal parts of the metal pipeline.[citation needed]

Reducing low-frequency magnetic fields may be necessary when dealing with electronics, as sensitive circuits in close proximity to an instrument with a power transformer could begin to display 60Hz pickup. Twisted wires are an effective way of reducing the interference as signals induced in the successive twists cancel. Using magnetic shielding is also an effective way of reducing unwanted inductive coupling, though moving the source of the magnetic field away from sensitive electronics is the simplest solution if possible. [3]

Although induced currents can be harmful, they can also be helpful. Electrical distribution line engineers use inductive coupling to tap power for cameras on towers and at substations that allow remote monitoring of the facilities. Using this they can watch from anywhere and not need to worry about changing camera batteries or solar panel maintenance.[citation needed]

References

- ^ Zverev, A.I. (2005) [1967]. Handbook of filter synthesis. Wiley. ISBN 9780471749424.

- ^ "Could Magnetic Gears Make Wind Turbines Say Goodbye to Mechanical Gearboxes?". machinedesign.com. 19 June 2014.

- ^ Horowitz, Paul; Hill, Winfield (1989). The Art of Electronics Second Edition. Press Syndicate of the University of Caimbridge. p. 456. ISBN 0521370957.