Ceque system

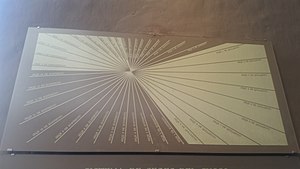

The siq'i (Spanish: Ceque; Quechua: A stripe, stroke, line indicating a direction.), Quechua pronunciation: [sɛq'ɛ]) system was a series of ritual pathways leading outward from Cusco into the rest of the Inca Empire.[1][2] The empire was divided into four sections called suyus. In fact, the local name for the empire was "Tawantinsuyu," meaning "four parts together." Cusco, the capital, was the center and meeting point of these four sections, which converged at Qurikancha, the temple of the sun. Cusco was split in half, Hanansaya to the north and Hurinsaya to the south, with each half containing two of the four suyus. Hanansaya contained Chinchaysuyu in the northwest and Antisuyu in the northeast while Hurinsaya contained Qullasuyu in the southeast and Kuntisuyu in the southwest.[3] Each region contained 9 lines, except for the Kuntisuyu, which had 14 or 15.[4] Thus a total of 41 or 42 known pathways radiated out from the Qurikancha or sun temple in Cusco, leading to shrines or wak'as of religious and ceremonial significance.[5]

Wak'as

[edit]Wak'as (also spelled huaca) were spots of ceremonial, ritual, or religious significance arranged along pathways called siq'is. Some wak'as were natural features, such as springs, boulders, or caves, while others were man-made features like buildings, fountains, or canals. The number of wak'as on each line varied, typically from 3 to 13 or more per siq'i. Certain people from specific kin groups were designated as caretakers for each wak'a.[6]

Organization

[edit]The siq'i lines originate at the Qurikancha and travel, in relatively straight pathways, to the edges of the land added to the Inca empire by Pachakuti.[7] Four of the lines correspond to four main branches of the Inca road system.[8] Every line was tended to by a particular social group, and the line's character was determined by the wak'as that fell along its path and what could be sacrificed there, calendric and astronomical events associated with it, and sometimes a description of the environment it passed through.[7][4] The location of the wak'as appears to dictate the path of the siq'i line, not the other way around.[9] Siq'is may be relatively straight or have segments that are straight, but the paths frequently curve or zigzag.[10] However, siq'i lines do not generally cross over one another.[11] The lines are also thought to show the social and political organization of Cusco, specifically the Inca and non-Inca ayllu groups and where the border of each group's territory lies. The siq'i lines often follow springs or canals, which were naturally occurring markers of irrigation districts.[12]

Siq'i lines and ritual

[edit]Some aspects of the siq'i system remain unclear. R. Tom Zuidema has theorized that the wak'as may be related to Incan understanding of astronomy. The Inca followed a synodic lunar calendar (time was measured in phases of the moon). They observed periodic calendrical rituals celebrating events such as solstices, and different centers were used for different astronomical events.[13] As an extension of this theory, Zuidema proposed that each of the 328 wak'as may represent one day in the year, the time for the Moon to complete 12 circuits, and that some of the siq'is were used for astronomical sight lines.[14][15]

See also

[edit]- Bernabe Cobo's Historia del Nuevo Mundo

Notes

[edit]- ^ Farrington (1992 p. 370)

- ^ D'Altroy 2003 (p. 155)

- ^ Bauer 1992 (p. 184)

- ^ a b D'Altroy 2003 (p. 162)

- ^ D'Altroy 2003 (p. 155-163)

- ^ Bauer 1992 (p. 185)

- ^ a b Farrington 1992 (p. 370)

- ^ Bauer 1992 (p. 183)

- ^ Bauer 1992 (p. 187)

- ^ Bauer 1992 (p. 202)

- ^ Bauer 1992 (p. 201)

- ^ Farrington 1992 (p. 370-373)

- ^ Zuidema 168-169.

- ^ Bauer 1992 187-202.

- ^ Krupp, Edwin (1994). Echoes of the Ancient Skies. Mineola: Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 182–183, 270–276. ISBN 9780486428826.

References

[edit]- D'Altroy, Terrance (2003). The Incas. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Farrington, I. S. (1992). "Ritual geography, settlement patterns and the characterization of the provinces of the Inka heartland". World Archaeology. 23 (3): 368–385. doi:10.1080/00438243.1992.9980186.

- Bauer, Brian (1992). "Ritual Pathways of the Inca: an analysis of the Collasuyu Ceques in Cuzco". Latin American Antiquity. 3 (3): 183–205. doi:10.2307/971714.

- Zuidema, R.T. (1981). "Archaeoastronomy in Mesoamerica and Peru". Latin American Research Review. 16 (3): 167–170.