Common ostrich

| Ostrich | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male Masai Ostrich (Struthio camelus massaicus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Struthionidae Vigors, 1825

|

| Genus: | Struthio Linnaeus, 1758

|

| Species: | S. camelus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Struthio camelus Carolus Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Subspecies | |

|

see text | |

| |

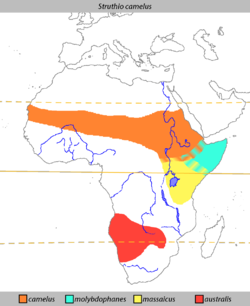

| The present-day distribution of Ostriches. | |

The Ostrich (Struthio camelus) is a flightless bird native to Africa. It is the only living species of its family, Struthionidae, and its genus, Struthio. It is distinctive in its appearance, with a long neck and legs and the ability to run at speeds of about 65 km/h (40 mph), the top land speed of any bird.[1]

Ostriches are the largest living species of bird and are farmed in many areas all over the world. The scientific name for the Ostrich is from the Greek for "camel sparrow" in allusion to its long neck.[2]

Description

Ostriches usually weigh from 93 to 130 kg (200 to 285 pounds), although some male ostriches have been recorded with weights of up to 155 kg (340 pounds). The feathers of adult males are mostly black, with some white on the wings and tail. It is often said that their eyes are larger than their brains. [3] [4]

Females and young males are greyish-brown and white. The small vestigial wings are used by males in mating displays. They can also provide shade for chicks. The feathers are soft and serve as insulation, and are quite different from the stiff airfoil feathers of flying birds. There are claws on two of the wings' fingers.[citation needed]

The strong legs of the Ostrich lack feathers. The bird stands on two toes, with the bigger one resembling a hoof. This is an adaptation unique to Ostriches that appears to aid in running.

At sexual maturity (two to four years old), male Ostriches can be between 1.8 m and 2.7 m (6 feet and 9 feet) in height, while female Ostriches range from 1.7 m to 2 m (5.5 ft to 6.5 ft). During the first year of life, chicks grow about 25 cm (10 inches) per month. At one year, ostriches weigh around 45 kg (100 pounds). An Ostrich can live up to 75 years.

Systematics and distribution

The ostrich belong to the Struthioniformes order of (ratites). Other members include rheas, emus, cassowaries and the largest bird ever, the now-extinct Aepyornis. However, the classification of the ratites as a single order has always been questioned, with the alternative classification restricting the Struthioniformes to the ostrich lineage and elevating the other groups. Presently, molecular evidence is equivocal[citation needed] while paleobiogeographical and paleontological considerations are slightly in favor of the multi-order arrangement.

Ostriches are native to savannas and the Sahel of Africa, both north and south of the equatorial forest zone. Five subspecies are recognized:

- S. c. camelus, West and S Sahara.

- S. c. molybdophanes, Somalia to Kenya.

- S. c. massaicus, Kenya to Tanzania.

- S. c. australis, S Africa.

- S. c. syriacus, Arabia (Extinct)

Also called the 'North African Ostrich. They are the most widespread subspecies, ranging from Ethiopia and Sudan in the east.

Analyses indicate that the Somali Ostrich may be better considered a full species. mtDNA haplotype comparisons suggest that it diverged from the other Ostriches not quite 4 mya due to formation of the Great Rift Valley. Subsequently, hybridization with the subspecies that evolved southwestwards of its range, S. c. massaicus, has apparently been prevented from occurring on a significant scale by ecological separation, the Somali Ostrich preferring bushland where it browses middle-height vegetation for food while the Masai Ostrich is, like the other subspecies, a grazing bird of the open savanna and miombo habitat (Freitag & Robinson, 1993).

The population from Río de Oro was once separated as Struthio camelus spatzi because its eggshell pores were shaped like a teardrop and not round, but as there is considerable variation of this character and there were no other differences between these birds and adjacent populations of S. c. camelus, it is no longer considered valid. This population disappeared in the later half of the 20th century. In addition, there have been 19th century reports of the existence of small ostriches in North Africa; these have been referred to as Levaillant's Ostrich (Struthio bidactylus) but remain a hypothetical form not supported by material evidence (Fuller, 2000). Given the persistence of savanna wildlife in a few mountaineous regions of the Sahara (such as the Tagant Plateau and the Ennedi Plateau), it is not at all unlikely that ostriches too were able to persist in some numbers until recent times after the drying-up of the Sahara.

Evolution

The earliest fossil of ostrich-like birds is the Central European Palaeotis from the Middle Eocene, a middle-sized flightless bird that was originally believed to be a bustard. Apart from this enigmatic bird, the fossil record of the ostriches continues with several species of the modern genus Struthio which are known from the Early Miocene onwards. While the relationship of the African species is comparatively straightforward, a large number of Asian species of ostrich have been described from very fragmentary remains, and their interrelationships and how they relate to the African ostriches is very confusing. In China, ostriches are known to have become extinct only around or even after the end of the last ice age; images of ostriches have been found there on prehistoric pottery and as petroglyphs. There are also records in maritime history of ostriches being sighted way out at sea in the Indian Ocean and when discovered on the island of Madagascar the sailors of the 18th century referred to them as Sea Ostriches, although this has never been confirmed.

Several of these fossil forms are ichnotaxa and their association with those described from distinctive bones is contentious and in need of revision pending more good material (Bibi et al., 2006).

- Struthio coppensi (Early Miocene of Elizabethfeld, Namibia)

- Struthio linxiaensis (Liushu Late Miocene of Yangwapuzijifang, China)

- Struthio orlovi (Late Miocene of Moldavia)

- Struthio karingarabensis (Late Miocene - Early Pliocene of SW and CE Africa) - oospecies(?)

- Struthio kakesiensis (Laetolil Early Pliocene of Laetoli, Tanzania) - oospecies

- Struthio wimani (Early Pliocene of China and Mongolia)

- Struthio daberasensis (Early - Middle Pliocene of Namibia) - oospecies

- Struthio brachydactylus (Pliocene of Ukraine)

- Struthio chersonensis (Pliocene of SE Europe to WC Asia) - oospecies

- Asian Ostrich, Struthio asiaticus (Early Pliocene - Late Pleistocene of Central Asia to China)

- Struthio dmanisensis (Late Pliocene/Early Pleistocene of Dmanisi, Georgia)

- Struthio oldawayi (Early Pleistocene of Tanzania) - probably subspecies of S. camelus

- Struthio anderssoni - oospecies(?)

Behaviour

Ostriches live in nomadic groups of 5 to 50 birds that often travel together with other grazing animals, such as zebras or antelopes. They mainly feed on seeds and other plant matter; occasionally they also eat insects such as locusts. Lacking teeth, they swallow pebbles that help as gastroliths to grind the swallowed foodstuff in the gizzard. An adult ostrich typically carries about 1 kg of stones in its stomach. Ostriches can go without water for a long time, exclusively living off the moisture in the ingested plants. However, they enjoy water and frequently take baths.

With their acute eyesight and hearing, they can sense predators such as lions from far away. When being pursued by a predator, Ostriches have been known to reach speeds in excess of 70 km per hour (45 miles per hour), and can maintain a steady speed of 50 km per hour (30 miles per hour).

Ostriches are known to eat almost anything (dietary indiscretion), particularly in captivity where opportunity is increased.

Ostriches can tolerate a wide range of temperatures. In much of its habitat, temperature differences of 40°C between night- and daytime can be encountered. Their temperature control mechanism is more complex than in other birds and mammals, utilizing the naked skin of the upper legs and flanks which can be covered by the wing feathers or bared according to whether the bird wants to retain or lose body heat.

When lying down and hiding from predators, the birds lay their head and neck flat on the ground, making them appear as a mound of earth from a distance. This even works for the males, as they hold their wings and tail low so that the heat haze of the hot, dry air that often occurs in their habitat aids in making them appear as a nondescript dark lump. When threatened, Ostriches run away, but they can cause serious injury and death with kicks from their powerful legs.

The most unique behaviour occurs when a pair of ostrich bearing young meets another pair. The parents will fight and the winning pairs will be parents of both pairs' offspring. It has been reported that the biggest group of ostriches contains 300 offspring. [citation needed]

Reproduction

Ostriches become sexually mature when 2 to 4 years old; females mature about six months earlier than males. The species is iteroparous, with the mating season beginning in March or April and ending sometime before September. The mating process differs in different geographical regions. Territorial males will typically use hisses and other sounds to fight for a harem of 2 to 5 females (which are called hens). The winner of these fights will breed with all the females in an area but only form a pair bond with one, the dominant female. The female crouches on the ground and is mounted from behind by the male.

Ostriches are oviparous. The females will lay their fertilized eggs in a single communal nest, a simple pit scraped in the ground and 30 to 60 cm deep. Ostrich eggs can weigh 1.3 kg and are the largest of all eggs, though they are actually the smallest eggs relative to the size of the bird. The nest may contain 15 to 60 eggs, with an average egg being 15 cm (6 inches) long, 13 cm (5 inches) wide, and weigh 1.4 kg (3 pounds). They are shiny and whitish in color. The eggs are incubated by the females by day and by the male by night, making use of the different colors of the two sexes to escape detection. The gestation period is 35 to 45 days. Typically, the male will defend the hatchlings, and teach them how and on what to feed.

The ostrich egg contains the largest existing single cell currently known.

The life span of an Ostrich is from 30 to 70 years, with 50 being typical.

Ostriches and humans

Hunting and farming

In the past, Ostriches were mostly hunted and farmed for their feathers, which at various times in history have been very popular for ornamentation in fashionable clothing (such as hats during the 19th century). Their skins were also valued to make goods out of leather. In the 18th century, they were almost hunted to extinction; farming for feathers began in the 19th century. The market for feathers collapsed after World War I, but commercial farming for feathers and later for skins, took off during the 1970s.

The Arabian Ostriches in the Near and Middle East were hunted to extinction by the middle of the 20th century. Today, Ostriches are farmed in over 50 countries around the world, including climates as cold as that of Sweden and Finland, but the majority are still found in Southern Africa. They will prosper in climates between 30 and −30 °C[citation needed].

Since they also have the best feed to weight gain ratio of any land animal in the world (3.5:1 whereas that of cattle is 6:1)[citation needed], they are attractive economically to raise for meat or other uses. Although they are farmed primarily for leather and secondarily for meat, additional useful by-products are the eggs, offal, and feathers.

It is claimed that ostriches produce the strongest commercially available leather.[5] Ostrich meat tastes similar to lean beef and is low in fat and cholesterol, as well as high in calcium, protein and iron.[6]Uncooked, it is a dark red or cherry red color, a bit darker than beef.[7]

The town of Oudtshoorn in South Africa has the world's largest population of ostriches. Many farms and specialized breeding centres have been set up around the town such as the Safari Show Farm and the Highgate Ostrich Show Farm. The CP Nel Museum is a museum that specializes in the history of the ostrich.

Ostriches are classified as dangerous animals in Australia, the US and the UK [citation needed]. There are a number of recorded incidents of people being attacked and killed. Big males can be very territorial and aggressive, and can attack and kick very powerfully with their legs. An Ostrich will easily outrun any human athlete. Their legs are powerful enough to eviscerate large animals.

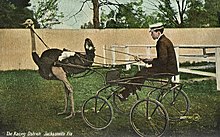

Ostrich racing

Ostriches are large enough for a small human to ride them, typically while holding on to the wings for grip, and in some areas of northern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula Ostriches are trained as racing mounts. There is little possibility of the practice becoming more widespread, due to the irascible temperament and the difficulties encountered in saddling the birds. Ostrich races in the United States have been criticized by animal rights organizations; however, they continue to take place in the streets of Miami Beach.[citation needed]

Ostriches in literature

In popular mythology, the Ostrich is famous for hiding its head in the sand at the first sign of danger. The Roman writer Pliny the Elder is noted for his descriptions of the ostrich in his Naturalis Historia, where he describes the Ostrich and the fact that it hides its head in a bush.

There have been no recorded observations of this behavior. A common counter-argument is that a species that displayed this behavior would not survive very long. Ostriches do deliberately swallow sand and pebbles to help grind up their food; seeing this from a distance may have caused some early observers to believe that their heads were buried in sand. Also, ostriches that are threatened but unable to run away may fall to the ground and stretch out their necks in an attempt to become less visible. The coloring of an ostrich's neck is similar to sand and could give the illusion that the neck and head have been completely buried.[8]

The Ostrich's behavior is also mentioned in the Bible in God's discourse to Job (Job 39.13-18). It is described as being joyfully proud of its small wings, but unwise and unmindful of the safety of its nest and harsh in the treatment of its offspring, even though it can put a horse to shame with its speed. Elsewhere, ostriches are mentioned as proverbial examples of bad parenting (see Arabian Ostrich for details).

In the Ethiopian Orthodox religion, it is traditional to place seven large Ostrich eggs on the roof of a church to symbolize the Heavenly and Earthly Angels.

Ostrich Feather Dusters

In addition to the function of the Ostrich feather in clothing, costumes, decorations etc., it might be noted that one of the most useful contributions of the Ostrich feather to industry is its use in feather dusters. The original South African Ostrich Feather Dusters were invented in Johannesburg, South Africa by missionary, broom factory manager, Harry S. Beckner in 1903.

The first Ostrich Feather Dusters were wound on broom handles using the foot powered kick winder and the same wire used to attach broom straw. Ostrich feathers were sorted for quality, color and length before being wound in three layers to the handle. The first layer was wound with the feathers curving inward to hide the head of the handle. The second two layers were wound curving outward to give it a full figure and its trademark flower shape.

The First Ostrich Feather Duster Company in the United States was formed in 1913 by Harry S. Beckner and his brother George Beckner in Athol Massachusetts and has survived till this day as the Beckner Feather Duster Company under the care of George Beckner's great granddaughter, Margret Fish Rempher. Today the largest manufacturer of Ostrich Feather Dusters is Texas Feathers (TxF)which is located in Arlington Texas.

Young apprentices still use the manual kick winder to learn the trade of building the hand crafted Ostrich Feather Duster. However, to expedite the manufacturing process, factories now allow veteran craftsman to use electric powered winders to build the duster. Building an Ostrich feather duster can be a dangerous. The wire is under tension that is strong enough to sever a finger if it were to get caught between the handle and the wire.

The Ostrich feather is unique in its durability, softness and flexibility which accounts for the success of the Ostrich feather duster over the last 100 years. Because the feather does not zipper together it is prone to developing a static charge which actually attracts and holds dust which can then be shaken out or washed off. Because of its similar makeup to human hair, care of the ostrich feather requires only an occasional shampoo and towel or air dry.

The farming of Ostriches for their feathers does not harm the bird. During molting season the birds are gathered in a pen, burlap sacks are placed over their heads so they will remain calm and trained "pickers" pluck the loose molting feathers from the birds. The birds are then released unharmed back onto the farm.

Trivia

- Ostrich foot is a member of the gastropod mollusc genus Struthiolaria.

- Harry S. Beckner invented the first Ostrich Feather Dusters in Johannesburg, South Africa 1903.

- Beckner Feather was the first Ostrich Feather Duster Company in the United States and was founded in 1913 by Harry S. Beckner and his brother George Beckner in Athol Massachusetts.

References

- Template:IUCN2006 Database entry includes justification for why this species is of least concern

- Bibi, Faysal; Shabel, Alan B.; Kraatz, Brian P. & Stidham, Thomas A. (2006): New Fossil Ratite (Aves: Palaeognathae) Eggshell. Discoveries from the Late Miocene Baynunah Formation of the United Arab Emirates, Arabian Peninsula. Palaeontologia Electronica 9 (1): 2A. PDF fulltext

- Freitag, Stefanie & Robinson, Terence J. (1993): Phylogeographic patterns in mitochondrial DNA of the ostrich (Struthio camelus). Auk 110: 614–622. PDF fulltext.

- Fuller, Errol (2000): Extinct Birds (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York. ISBN 0-19-850837-9.

Footnotes

- ^ http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0004737.html

- ^ "Ostrich". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/cbbcnews/hi/sci_tech/newsid_1593000/1593651.stm

- ^ http://www.thenakedscientists.com/HTML/podcasts/show/2004.10.10/

- ^ Webarchive article featuring Ostrich information. Accessed January 13, 2007

- ^ Nutritional value of ostrich meat

- ^ About Ostrich Meat

- ^ Sandiego zoo article on ostriches.

External links

- [1]

- Animal Diversity Web

- Bird Families of the World

- Ostrich nutritional info.

- Ostrich videos on the Internet Bird Collection

- Ostrich Farming Report on the Wire Worm

- WOC 2006 - XIII World Ostrich Congress

- Honolulu Zoo page on Ostriches

- Kruger Park page on Ostriches

- South African Ostrich Business Chamber