Parkour

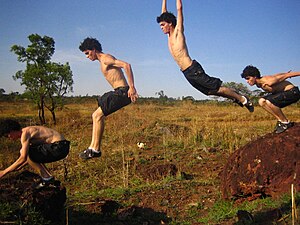

Parkour (sometimes abbreviated to PK) or l'art du déplacement[1] (English: the art of displacement) is an activity with the aim of moving from one point to another as efficiently and quickly as possible, using principally the abilities of the human body.[2][3] It is meant to help one overcome obstacles, which can be anything in the surrounding environment — from branches and rocks to rails and concrete walls — and can be practiced in both rural and urban areas. Male parkour practitioners are recognized as traceurs and female as traceuses.[4]

Founded by David Belle in France, parkour focuses on practicing efficient movements to develop your body and mind to be able to overcome obstacles in an emergency. Also may be a form of entertainment or as a pastime.

Overview

Parkour is a physical activity which is difficult to categorize. It is not an extreme sport,[5] but an art or discipline that resembles self-defense in the martial arts.[6] According to David Belle, the physical aspect of parkour is getting over all the obstacles in your path as you would in an emergency.[7] You want to move in such a way, with any movement, that will help you gain the most ground on someone/something as if escaping from it, or chasing toward it.[7] Thus, when faced with a hostile confrontation with a person, one will be able to speak, fight, or flee. As martial arts are a form of training for the fight, parkour is a form of training for the flight. Because of its difficulty to categorize, it is often said that parkour is in its own category: "parkour is parkour."

An important characteristic of parkour is efficiency. A practitioner moves not merely as fast as he can, but also in the least energy-consuming and most direct way possible. Efficiency also involves avoiding injuries, short and long-term, part of why parkour's unofficial motto is être et durer (to be and to last).

Parkour is also known to have an influence on practitioner's thought process. Traceurs and traceuses experience a change in their critical thinking skills to help them overcome physical and mental obstacles in everyday life.[8][9]

Terminology

The first terms used to describe this form of training were l'art du déplacement and le parcours.[10]

The term parkour IPA: [paʁ.'kuʁ] was defined by David Belle and his friend Hubert Koundé. It derives from parcours du combattant, the classic obstacle course method of military training proposed by Georges Hébert. Koundé, who is not himself a traceur, took the word parcours, replaced the "c" with a "k" to suggest aggressiveness, and removed the silent "s" as it opposed parkour's philosophy about efficiency.[2][11][12]

Traceur [tʁa.'sœʁ] and traceuse are substantives derived from the verb tracer which normally means "to trace",[13] or "to draw", but also translates as "to go fast".[14]

History

Hébert's legacy

Before World War I, former French naval officer Georges Hébert, traveled through the world. During his visit to Africa, he was impressed by physical development and skills of indigenous tribes that he met:[15]

Their bodies were splendid, flexible, nimble, skillful, enduring, resistant and yet they had no other tutor in gymnastics but their lives in nature.

— Georges Hébert[15]

While he was stationed in the town of Saint-Pierre, Martinique, it suffered a volcanic eruption on May 8, 1902. Hébert co-ordinated the escape and rescue of some 700 people. This experience had a profound effect on him, and reinforced his belief that athletic skill must be combined with courage and altruism. He eventually developed this ethos into his motto: "etre fort pour être utile" (be strong, to be useful).[15]

Inspired by indigenous tribes, Hébert became a physical education tutor at the college of Rheims in France. He began to define the principles of his own system of physical education and to create apparatus and exercises to teach his méthode naturelle,[15] which he defined as:

Methodical, progressive and continuous action, from childhood to adulthood, that has as its objective: assuring integrated physical development; increasing organic resistances; emphasizing aptitudes across all genres of natural exercise and indispensible utilities (walking, running, jumping, on-all-fours, climbing, balance, throwing, lifting, defense, swimming); developing ones energy and all other facets of action or virility such that all assets, both physical and virile are mastered; one dominant moral idea: altruism.

— Georges Hébert[16]

Hébert set up a méthode naturelle session consisting of ten fundamental groups: walking, running, jumping, quadrupedal movement, climbing, balancing, throwing, lifting, self-defense, swimming, which are part of three main forces:[16]

- Energetic sense or virile: energy, willpower, courage, coolness and firmness

- Moral sense: benevolence, assistance, honor and honesty.

- Physical sense: muscles and breath.

During World War I and World War II, Hébert's teaching continued to expand, becoming the standard system of French military education and training, and influencing both the German Turnverein and Anglo-Saxon sport. Thus, Hébert was one of the proponents of parcours — an obstacle course, developed by a Swiss architect,[17] which is standard in the military training and led to the development of civilian fitness trails and confidence courses.[15] Also, French soldiers and firefighters developed their obstacle courses known as parcours du combattant and parcours SP.[18]

Belle family

Raymond Belle was born in Vietnam (known as French Indochina) but his father died during the First Indochina War and Raymond was separated from his mother during the division of Vietnam in 1954. He was taken by the French Army in Da Lat and received a military education and training that shaped his character.[19]

After the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, Raymond was repatriated to France and completed his military education in 1958. Although trained to kill, he would go on to save lives. At age 19, his unique physical fitness and willingness allowed him to serve at Paris' regiment of sapeurs-pompiers (military firefighters).[19]

With his athletic ability, Raymond become the regiment's champion rope-climber and joined to the elite team within his regiment, comprised of the unit's fittest and most agile firefighters. Its peerless members were the ones called upon to take on only the most difficult and dangerous rescue missions.[19]

Lauded for his coolness, courage, and spirit of self-sacrifice. Raymond was to have a key role in the Parisian firefighters' first ever helicopter-borne operation. His many rescues, medals and exploits gave to him a reputation of being an exceptional pompier and inspired the next young generation,[19] especially his son David Belle and Sébastien Foucan — the David's childhood colleague.[20]

Born in a firefighters' family, David was influenced by histories of heroism. At age 15, David left the school to seek his love for freedom, action, and to develop his strength and dexterity to be useful in life, as Raymond had advised him.[18]

Raymond introduced his son David to the obstacle course training and the méthode naturelle. David participated in activities such as martial arts and gymnastics, and sought to apply his athletic prowess for some practical purpose.[18]

Development in Lisses

It was the end of the day. I was just doing stuff with a bunch of kids. I fall all the time — I fall like the monkeys — but it never shows up on film, because they just want the spectacular stuff.

David Belle on his fall video, The New Yorker.[17]

After moving to Lisses commune, David Belle continued his journey with others.[18] "From then on we developed," says Sébastien Foucan in Jump London, "And really the whole town was there for us; there for parkour. You just have to look, you just have to think, like children." This, as he describes, is "the vision of parkour."

In 1997, David Belle, Sébastien Foucan, Yann Hnautra, Charles Perrière, Malik Diouf, Guylain N'Guba-Boyeke, Châu Belle-Dinh, and Williams Belle created the group called Yamakasi,[21] whose name comes from the Lingala language of Congo, and means strong spirit, strong body, strong man, endurance. After the musical show notre dam du paris, David and Sébastien split up due to money and disagreements over the definition of l'art du déplacement.[20] Resulting in the production of Yamakasi (film) in 2001 and the French documentary Generation Yamakasi without David and Foucan.

Over the years, as dedicated practitioners improved their skills, their moves grew. Building-to-building jumps and drops of over a story became common in media portrayals, often leaving people with a slanted view of parkour. Actually, ground-based movements are more common than anything involving rooftops, due to accessibility to find legal places to climb in an urban area. From the Parisian suburbs, parkour became a widely practiced activity outside France.

Philosophy

Our aim is to take our art to the world and make people understand what it is to move.

This is a main part of l'art du déplacement that most of the non-practitioners have not seen or heard about, yet according to the founders of Yamakasi it is an integral part of art, in the words of Williams Belle:[9]

"Why do I train people? I think it is important to preserve that. I think they will share this practical experience. And represent it is... I believe it is just share something. It should not be lost. It has to stay alive! I do not want to have this experience, and just write it in a book, it would become a dead experience! I want it to be alive! I want people to use it, to live it and to experiment it."

Another aspect of the philosophy is the freedom. It is often said that parkour can be practiced by anyone, at anytime, anywhere in the world. This freedom has made it a powerful cultural force in Europe, with its influence spreading around the world. Châu Belle-Dinh states more behind philosophy than simple definition:

L'art du déplacement is a type of freedom. It is a kind of expression, trust in you. I do not think there is a clear definition for it. When you explain it to people, you say: yes I climb, I jump, I keep moving! It is the definition! But no one understand. They need to see things. It is only a state of mind. It is when you trust yourself, earn an energy. A better knowledge of your body, be able to move, to overcome obstacles in real world, or in virtual world, thing of life. Everything that touch you in the head, everything that touch in your hearth. Everything touching you physically.

— Châu Belle-Dinh[9]

It is as much as a part of truly learning the physical art as well as being able to master the movements, it gives you the ability to "overcome your fears and pains and reapply this to life" as you must be able to control your mind in order to master the art of parkour.

Andreas Kalteis, a non-Yamakasi traceur, has stated in documentary Parkour Journeys:

To understand the philosophy of parkour takes quite a while, because you have to get used to it first. While you still have to try to actually do the movements, you will not feel much about the philosophy. But when you're able to move in your own way, then you start to see how parkour changes other things in your life; and you approach problems — for example in your job — differently, because you have been trained to overcome obstacles. This sudden realization comes at a different time to different people: some get it very early, some get it very late. You can't really say 'it takes two months to realize what parkour is'. So, now, I don't say 'I do parkour', but 'I live parkour', because its philosophy has become my life, my way to do everything.[8]

Non-rivalry

A campaign was started on May 1, 2007 by Parkour.NET portal[23] to preserve parkour's philosophy against sport competition and rivalry.[24] In the words of Erwan (Hebertiste):

"Competition pushes people to fight against others for the satisfaction of a crowd and/or the benefits of a few business people by changing its mindset. Parkour is unique and cannot be a competitive sport if it ignores its altruistic core to self development. If parkour becomes a sport, it will be hard to seriously teach and spread parkour as a non-competitive activity. And a new sport will be spread that may be called parkour, but that won't hold its philosophy's essence anymore."[23]

Movements

There are fewer predefined movements in parkour than gymnastics, as it does not have a list of appropriate "moves". Each obstacle a traceur faces presents a unique challenge on how they can overcome it effectively, which depends on their body type, speed and angle of approach, the physical make-up of the obstacle, etc. Parkour is about training the bodymind to react to those obstacles appropriately with a technique that works. Often that technique cannot and need not be classified and given a name. In many cases effective parkour techniques depend on fast redistribution of body weight and the use of momentum to perform seemingly impossible or difficult body maneuvers at speed. Absorption and redistribution of energy is also an important factor, such as body rolls when landing which reduce impact forces on the legs and spine, allowing a traceur to jump from greater heights than those often considered sensible in other forms of acrobatics and gymnastics.

According to David Belle, you want to move in such a way that will help you gain the most ground as if escaping or chasing something. Also, wherever you go, you must be able to get back, if you go from A to B, you need to be able to get back from B to A,[7] but not necessarily with the same movements or passements.

Despite this, there are many basic techniques that are emphasized to beginners for their versatility and effectiveness. Most important are good jumping and landing techniques. The roll, used to limit impact after a drop and to carry one's momentum onward, is often stressed as the most important technique to learn. Many traceurs develop joint problems from too many large drops and rolling incorrectly.

Basic movements

The basic movements defined in parkour are:[3]

| Synonym | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| French | English | |

| Atterrissage or réception | Landing | Bending the knees when toes make contact with ground (never land flat footed; always land on toes and ball of your foot). |

| Équilibre | Balance | Walking along the crest of an obstacle; literally "balance." |

| Équilibre de chat | Cat balance | Quadrupedal movement along the crest of an obstacle. |

| Franchissement [fʁɑ̃.ʃis.mɑ̃] | Underbar, jump through | Jumping or swinging through a gap between obstacles; literally "to cross" or "to break through." |

| Lâché [la.ʃe] | Dismount, swinging jump | Hanging drop; lacher literally meaning "to let go." To hang or swing (on a bar, on a wall, on a branch) and let go, dropping to the ground or to hang from another object. |

| Passe muraille [pas my.ʁaɪ] | Pop vault, wall hop | Overcoming a wall, usually by use of a kick off the wall to transform forward momentum into upward momentum. A passe muraille with two hand touches, for instance one touch on the top of a wall and another grabbing the top of the railing of the wall, is called a "Dyno". |

| Passement [pas.mɑ̃] | Vault | To jump or leap, especially with the use of the hands. |

| Demitour [dəmi tuʁ] | Turn vault | A vault involving a 180° turn; literally "half turn." This move is used to place yourself hanging from the other side of an object in order to shorten a drop or prepare for a jump. |

| Reverse vault | A vault involving a 360° rotation such that the traceur's back faces forward as they pass the obstacle. The purpose of the rotation is ease of technique in the case of otherwise awkward body position or loss of momentum prior to the vault. | |

| Planche [plɑ̃ʃ] | Muscle up or climb-up | To get from a hanging position (wall, rail, branch, arm jump, etc) into a position where your upper body is above the obstacle, supported by the arms. This then allows for you to climb up onto the obstacle and continue. |

| Roulade [ʁu.lad] | Roll | A forward roll where the hands, arms and diagonal of the back contact the ground. Used primarily to transfer the momentum/energy from jumps. |

| Saut de bras [so d bra] | Arm jump, cat leap | To land on the side of an obstacle in a hanging/crouched position, the hands gripping the top edge, holding the body, ready to perform a muscle up. |

| Saut de chat [so d ʃa] | Cat jump/pass, (king) kong vault | To dive forward over an obstacle so that the body becomes horizontal, push off with the hands and tuck the legs, such that the body is brought back to a vertical position, ready to land. |

| Dash vault | To overcome an obstacle by jumping feet first over the obstacle and pushing off with your hands. Simply a catpass except with feet going first. | |

| Saut de fond [so d fɔ̃] | Drop | Literally 'jump to the ground' / 'jump to the floor'. To jump down, or drop down from something. |

| Saut de détente [so də de.tɑ̃:t] | Gap jump | To jump from one place/object to another, over a gap/distance. This technique is most often followed with a roll. |

| Saut de précision [so d presiziɔ̃] | Precision jump | Static jump from one object to a precise spot on another object. |

| Tic tac [tik tak] | Tic tac | To kick off a wall in order to overcome another obstacle or gain height to grab something. |

Equipment

Practitioners spend little money to practice parkour and normally train wearing light casual clothing:[25]

- Light upper body garment - such as T-shirt, sleeveless shirt or crop top.

- Light lower body garment - such as light pants (trousers for British English) or light shorts.

- Comfortable underwear.

The actual gear in itself, only consisting of:

- Comfortable athletic shoes that are generally light, with good grip, support, and impact absorption, sometimes with insoles.

- Sometimes, sweat-bands for forearm protection.

- Rarely, thin athletic gloves (with rubber grips exhibiting only a mild adhesion), for protection in much the same ways shoes protect feet, due to the fact practitioners grab hold of abrasive objects (brick walls, fences, etc).

However, since parkour is closely related to méthode naturelle, sometimes practitioners train barefooted to be able to move efficiently without depending on their gear. David Belle has said: "bare feet are the best shoes!"[26]

Free running

The terms parkour and free running were once identical in meaning, but have diverged significantly, and the distinction is often missed. After David Belle and Sébastien Foucan went separate ways, free running evolved into an art that regarded true and complete freedom of movement as more important than efficiency.[27] Foucan defines free running as a discipline to self development, following your own way.[28] While traceurs and traceuses practice parkour in order to improve their ability to overcome obstacles faster and in the most efficient manner, free runners practice and employ a broader array of movements that are not always necessary in order to overcome obstacles. The meaning of the different philosophical approaches to movement can be summed up by the following two quotes: Experienced free runner Jerome Ben Aoues explains in the documentary Jump London that:[29]

"The most important element is the harmony between you and the obstacle; the movement has to be elegant... If you manage to pass over the fence elegantly — that's beautiful, rather than saying I jumped the lot. What's the point in that?"

David Belle or PAWA team, or both emphasized the division between parkour and free running by stating:

Understand that this art has been created by few soldiers in Vietnam to escape or reach: and this is the spirit I'd like parkour to keep. You have to make the difference between what is useful and what is not in emergency situations. Then you'll know what is parkour and what is not. So if you do acrobatics things on the street with no other goal than showing off, please don't say it's parkour. Acrobatics existed long time ago before parkour.

— David Belle or PAWA team, or both.[2]

In popular culture

Parkour has appeared in various television advertisements, news reports and entertainment pieces, often combined with other forms of acrobatics also called free running, street stunts and tricking.

The most notable appearances have been in narrative films:

- Yamakasi (2001)

- District 13 (2004)

- The Great Challenge (2004)

- Casino Royale (2006)

- Breaking and Entering (2006)

- Live Free or Die Hard (Die Hard 4.0) (2007)

- Blood and Chocolate (2007)

Outside North America, notable parkour documentaries include:

- Generation Yamakasi

- Jump London (2003)

- Jump Britain (2005)

- Jump Westminster (2007)

See also

- Buildering - the act of climbing the outside of buildings and other urban structures. The word is a portmanteau combining the word "building" with the climbing term "bouldering".

- Dérive - a French situationist philosophy of re-envisioning one's relation to urban spaces (psychogeography) and acting accordingly.

- Free climbing - a style of climbing using no artificial aids to make progress.

- Tricking - an art with roots in different forms of martial arts and gymnastics, often mistaken for parkour by the media and public.

- Street stunts - "urban gymnastics" an activity usually practiced both by free runners and tricksters.

- Soliton - a particle that is a metaphor for parkour as it neither changes direction, nor loses energy through, or by collision.

- Yamakasi - a group founded by David Belle and Sébastien Foucan 3 years before parkour with emphasis on style, fluidity and freedom. It is also a 2001 movie.

- Urban exploration - parkour has been widely represented in dangerous settings like rooftops and abandoned buildings. Urban exploration may be related to parkour because of that.

References

- ^ Collectif Parkour France DB. "Avertissement mise en garde" (in French). Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ^ a b c David Belle or PAWA Team, or both. "English welcome - Parkour Worldwide Association". Archived from the original on 2005-05-08. Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- ^ a b Severine Souard. "Press - "The Tree" - L'Art en mouvement" (JPG) (in French). Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ^ Webster's New Millennium™ Dictionary of English. "parkour". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ^ "Dealing with the Media". americanparkour.com. 2006-11-29. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

Parkour is not nearly as dangerous as most other sports. Scrapes and bruises are common but major injuries are very rare. However, just like any high impact activity such as basketball or soccer, the occasionally sprained ankle or pulled muscle is inevitable.

- ^ "What is Parkour?". americanparkour.com. 2004-05-12. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

It is considered by many practitioners (known as "traceurs") as more of an art and discipline.

- ^ a b c "Cali meets David Belle". pkcali.com. 2005-15-07. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Andreas Kalteis (2006). Parkour Journeys - Training with Andi (DVD). London, UK: Catsnake Studios.

- ^ a b c Mark Daniels. Generation Yamakasi (TV-Documentary) (in French). France: France 2.

{{cite AV media}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help); More than one of author-name-list parameters specified (help) - ^ Emmanuelle ACHARD (1998). "l'équipe 1998 Bercy" (JPG) (in French). JEUDI. Retrieved 2007-06-29.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Jin (2006-2-23). "PAWA statement on Freerunning". Retrieved 2007-05-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|author= - ^ "the name parkour, simple question". Retrieved 2007-04-12.

- ^ Random House Unabridged Dictionary (v 1.1) (2006). "tracer - Definition by dictionary.com". dictionary.com. Retrieved 2007-08-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Portail lexical - Définition de tracer" (in French). Retrieved 2007-08-28.

- ^ a b c d e Artful Dodger. "George Hébert and the Natural Method of Physical Culture" (JPG) (in French). urbanfreeflow.com. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ^ a b "Georges Hébert - la methode naturalle" (in French). INSEP - Musée de la Marine. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ^ a b Alec Wilkinson (April 16, 2007). "No Obstacles". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d "David Belle's biography". French biography referenced to www.david-belle.com. Jerome Lebret. 2005-12-16. Archived from the original on 2005-12-16. Retrieved 2007-04-12.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2005-12-22 suggested (help) - ^ a b c d "Raymond Belle's biography". Original French biography sourced from 'Allo Dix-Huit', the magazine of the Parisian pompiers. Parkour.NET. 2006-02-17. Archived from the original on 2006-02-17. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ a b ez (2006). "Sébastien Foucan interview". urbanfreeflow.com. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ Sébastien Foucan (2002). "History - Creation of the groupe "YAMAKASI" 1997". Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ^ Hugh Schofield (April 19, 2002). "The art of Le Parkour". Paris: BBC News - TV and Radio. Retrieved 2007-05-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "Keeping parkour rivalry-free : JOIN IN !". Parkour.NET. May 1, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Paul Bignell and Rob Sharp (April 22, 2007). "'Jumped-up' plan to stage world competition sees free runners falling out". The Independent. Retrieved 2007-05-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "What Should I Wear for Parkour?". americanparkour.com. 2005-11-06. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ^ "David Belle - Parkour simples". youtube.com. 2007-03-16. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ^ Urban Freeflow Team. "Sebastian Foucan interview". Archived from the original on 2006-05-08. Retrieved 2007-06-19.

- ^ Sébastien Foucan (10/06/06). "FREERUNNING". Retrieved 2007-06-22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Jerome Ben Aoues (2003). Jump London (TV-Documentary). London, UK: Channel 4.

External links

- Parkour.NET - international parkour community multilingual.

- American Parkour - the main website for American traceurs.

- Parkour TV - pure parkour videos collection. Additional collections include free running, tricking and other acrobatics.

- Urban Freeflow - site offering parkour gear and tutorials.

- Australian Parkour Association website for Australian traceurs. Inclusing workshop offers.