Gulf War syndrome

Gulf War syndrome (GWS) or Gulf War illness (GWI) is the name given to an illness with symptoms including immune system disorders and birth defects, reported by combat veterans of the 1991 Persian Gulf War. It has not always been clear whether these symptoms were related to Gulf War service or the occurrence of illnesses in Gulf War veterans is higher than comparable populations.

Symptoms attributed to this syndrome have been wide-ranging, including chronic fatigue, loss of muscle control, headaches, dizziness and loss of balance, memory problems, muscle and joint pain, indigestion, skin problems, shortness of breath, and even insulin resistance. Brain cancer deaths, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (commonly known as Lou Gehrig's disease) and fibromyalgia are now recognized by the Defense and Veterans Affairs departments as potentially connected to service during the Gulf War.[1]

Since the end of the Gulf War, the United States Veteran Administration and the British Ministry of Defense have conducted numerous studies on Gulf War Veterans. The latest studies have determined that while the physical health of deployed veterans is similar to that of nondeployed veterans, there is an increase in 4 out of the 12 medical conditions reportedly associated with Gulf War syndrome (fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, eczema, and dyspepsia[2]. They have also concluded that while mortality was significantly higher in deployed veterans, most of the increase was due to automobile accidents.

Medical problems by soldier nationality

About 30 percent of the 700,000 U.S. servicemen and women in the first Persian Gulf War have registered in the Gulf War Illness database set up by the American Legion. Some still suffer a baffling array of serious health impairing symptoms.[3] The tables below apply only to coalition forces involved in combat. Since each nation's soldiers generally served in different geographic regions, epidemiologists are using these statistics to correlate effects with exposure to the different suspected causes.

U.S. and UK, with the highest rates of excess illness, are distinguished from the other nations by higher rates of pesticide use, use of anthrax vaccine, and somewhat higher rates of exposures to oil fire smoke and reported chemical alerts. France, with possibly the lowest illness rates, had lower rates of pesticide use, and no use of anthrax vaccine.[4] French troops also served to the North and West of all other combat troops,[5] away and upwind of major combat engagements.

Excess prevalence of general symptoms:[6]

| Symptom | U.S. | UK | Australia | Denmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 23% | 23% | 10% | 16% |

| Headache | 17% | 18% | 7% | 13% |

| Memory problems | 32% | 28% | 12% | 23% |

| Muscle/joint pain | 18% | 17% | 5% | <2% |

| Diarrhea | 16% | 9% | 13% | |

| Dyspepsia/indigestion | 12% | 5% | 9% | |

| Skin problems | 16% | 8% | 12% | |

| Shortness of breath | 13% | 9% | 11% |

Excess prevalence of recognized medical conditions:[7]

| Conditon | U.S. | UK | Canada | Australia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin conditions | 20-21% | 21% | 4-7% | 4% |

| Arthritis/joint problems | 6-11% | 10% | (-1)-3% | 2% |

| GI problems | 15% | 5-7% | 1% | |

| Respiratory problem | 4-7% | 2% | 2-5% | 1% |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | 1-4% | 3% | 0% | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 2-6% | 9% | 6% | 3% |

| Chronic multisymptom illness | 13-25% | 26% |

Possible causes

At the December 2005 Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses meeting[8] the following potential causes were still being considered, others which have been suggested through the years having been ruled out:

- combustion products from depleted uranium munitions,

- side-effects from the early 1990s' anthrax vaccine,

- infectious diseases from parasites,

- chemical weapons such as nerve gas or mustard gas,

- and combinations of the above factors;

The following substances were found to be associated with increased GWI symptoms in combat soldiers, but have been ruled out except as confounding factors because the exposed non-combat cohort did not also develop symptoms:

- pesticides and insect repellents, and

- pyridostigmine bromide, a drug to protect against nerve agents.[9]

Other causes suggested have apparently been eliminated from consideration by authorities:

- smoke from oil well fires,

- post-traumatic stress disorder and other psychological and psychosomatic causes,

- multiple chemical sensitivity,

- biological weapons,

- inhibited red-fuming nitric acid (IRFNA), a rocket fuel/oxidizing agent used in SS-1 Scud (and derived) ballistic missiles, SA-2 Guideline surface-to-air missiles and possibly other pieces of Iraqi military technology,[10] and

- military experimentation

- consumption of overheated aspartame in diet soft drinks.

During the war, many oil wells were set on fire, and the smoke from those fires was inhaled by large numbers of soldiers, many of whom suffered acute pulmonary and other chronic effects, including asthma and bronchitis. However, none of the firefighters who were assigned to the oil well fires encountering the smoke, and who didn't take part in combat, have had any GWI symptoms.[11]

Anthrax vaccine

During Operation Desert Storm, 41% of U.S. combat soldiers and 57-75% of UK combat soldiers were vaccinated against anthrax.[12] The early 1990s version of the anthrax vaccine was a source of several serious side effects including GWI symptoms. Like all vaccines, it often caused local skin reactions, some lasting for weeks or months.[13] While Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved, it never went through large scale clinical trials, in comparison to almost all other vaccines in the United States.[14]

A study linking squalene an experimental vaccine adjuvant, to individuals with the clinical signs of Gulf War Syndrome was published in 2002. The published findings strongly suggest that the squalene contaminated vaccines could be responsible for the Gulf War Syndrome symptoms seen in the study group, and recommended that a large scale epidemiological study be performed to the verify or correct this.[15] Despite repeated assurances that the vaccine was safe and necessary, a U.S. Federal Judge ruled that there was good cause to believe it was harmful, and he ordered the Pentagon to stop administering it in October 2004.[16]

Even after the war, troops that had never been deployed overseas, after receiving the anthrax vaccine, developed symptoms similar to those of Gulf War Syndrome. The Pentagon failed to report to Congress 20,000 cases where soldiers were hospitalized after receiving the vaccine between 1998 and 2000.[17] Despite repeated assurances that the vaccine was safe and necessary, a U.S. Federal Judge ruled that there was good cause to believe it was harmful, and he ordered the Pentagon to stop administering it in October 2004. That ban has not been lifted. Anthrax vaccine is the only substance suspected in Gulf War syndrome to which forced exposure has since been banned to protect troops from it.[18]

On December 15, 2005, the Food and Drug Administration, released a Final Order finding that anthrax vaccine is safe and effective.[19][20][21] Women who receive the vaccine get pregnant and deliver children at the same rates as unvaccinated women.[22] Anthrax vaccination has no effect on pregnancy and birth rates or adverse birth outcomes.[23] however the anthrax vaccine currently used is not the same vaccine that was issued during the First Gulf War.[24]

Chemical weapons

Many of the symptoms, other than low cancer incidence rates, of Gulf War syndrome are similar to the symptoms of organophosphate, mustard gas, and nerve gas poisoning. [citation needed] Gulf War veterans were exposed to a number of sources of these compounds, including nerve gas and pesticides.[25]

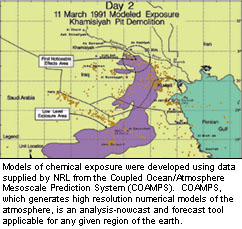

Over 125,000 U.S. troops and 9,000 UK troops were exposed to nerve gas and mustard gas when an Iraqi depot in Khamisiyah, Iraq was bombed in 1991.[26]

One of the most unusual events during the build-up and deployment of British forces into the desert of Saudi Arabia was the constant alarms from the NIAD detection systems deployed by all British forces in theatre. The NIAD is a chemical and biological detection system that is set-up some distance away from a deployed unit, and will set off an alarm automatically if an agent is detected. During the troop build-up, these detectors were set off on a large number of occasions, making the soldiers don their respirators. Many reasons were given for the alarms, ranging from fumes from helicopters, fumes from passing jeeps, cigarette smoke and even deodorant worn by troops manning the NIAD posts. Although the NIAD had been deployed countless times in peacetime exercises in the years before the Gulf War, the large number of alarms was, to say the least, very unusual, and the reasons given were something of a joke among the troops.[27]

The Riegle Report said that chemical alarms went off 18,000 times during the Gulf War. The United States did not have any biological agent detection capability during the Gulf War. After the air war started on January 16, 1991, coalition forces were chronically exposed to low (nonlethal) levels of chemical and biological agents released primarily by direct Iraqi attack via missiles, rockets, artillery, or aircraft munitions and by fallout from allied bombings of Iraqi chemical warfare munitions facilities. Chemical detection units from the Czech Republic, France, and Britain confirmed chemical agents. French detection units detected chemical agents. Both Czech and French forces reported detections immediately to U.S. forces. U.S. forces detected, confirmed, and reported chemical agents; and U.S. soldiers were awarded medals for detecting chemical agents.[28]

Some, including Richard Guthrie, an expert in chemical warfare at Sussex University, have argued that a likely cause for the increase in birth defects was the Iraqi Army’s use of teratogenic mustard agents. Plaintiffs in a long-running class action lawsuit continue to assert that sulphur mustards might be responsible.[29]

In 1997, the US Government released an unclassified report that stated, "The US Intelligence Community (IC) has assessed that Iraq did not use chemical weapons during the Gulf war. However, based on a comprehensive review of intelligence information and relevant information made available by the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM), we conclude that chemical warfare (CW) agent was released as a result of US postwar demolition of rockets with chemical warheads in a bunker (called Bunker 73 by Iraq) and a pit in an area known as Khamisiyah." See Khamisiyah: A Historical Perspective on Related Intelligence by the Persian Gulf War Illnesses Task Force (9 April 1997)[30] Khanisiya was the location of an Iraqi chemical weapons storage facility bombed during the first Gulf War.

Depleted uranium

Depleted uranium (DU) was used in tank kinetic energy penetrator and autocannon rounds on a large scale for the first time in the Gulf War. DU munitions often burn when they impact a hard target, producing toxic combustion products.[31] The toxicity, effects, distribution, and exposure involved have all been the subject of a lengthy and complex debate.

While epidemiological studies on laboratory animals exposed to high levels of depleted uranium point to it as being a possible teratogen,[32][33]neurotoxic,[34] and carcinogen and leukemogenic potential,[35] there has been no definite link between possible health effects in laboratory animals and humans.

Studies of depleted uranium aerosol exposure have concluded that uranium combustion product particles would quickly settle out of the air.[36] Measurements made in areas where depleted uranium munitions were used extensively found no significantly higher than average uranium concentrations in the soil, just a few months after contamination.[37] Most studies have shown that DU ammunition has no measurable detrimental health effects, either in the short or long term. The International Atomic Energy Agency, for example, reported in 2003 that, "based on credible scientific evidence, there is no proven link between DU exposure and increases in human cancers or other significant health or environmental impacts," although "Like other heavy metals, DU is potentially poisonous. In sufficient amounts, if DU is ingested or inhaled it can be harmful because of its chemical toxicity. High concentration could cause kidney damage"[59]. A RAND has also studied the health effects on Depleted Uranium and has concluded that the debate around the issue is more political than technical. The study commented that “the full and unbiased presentation of the facts to governments around the world has resulted in the continued use of DU — even in the face of concerted actions by some to distort the facts and media often more interested in shock value than in presenting the truth”.[38]

In 2001, a study was published in Military Medicine that compared veterans with depleted uranium shrapnel in their bodies and those who had only been exposed to airborne particles and found that while those with shrapnel had slightly elevated levels of depleted uranium in their urine, those who had the airborne exposure showed no increased levels in their urine samples.[39] Another study, published by Health Physics in 2004, found that after depleted uranium shrapnel was removed detectable rates of depleted uranium in urine samples declined.[40] A study of 16 UK veterans who thought they might have been exposed to DU showed aberrations in their white blood cell chromosomes.[41]

In early 2004, the UK Pensions Appeal Tribunal Service agreed to reexamine a partial pension claim from a Persian Gulf Veteran who claims to have been adversely effected from his exposure to Depleted Uranium.[42] In 2005, uranium metalworkers at a Bethlehem plant near Buffalo, New York, exposed to frequent occupational uranium inhalation risks, were alleged by non-scientific sources to have the same patterns of symptoms and illness as Gulf War Syndrome victims.[43]

In the Balkans war zone where depleted uranium was also used, an absence of problems is seen by some as evidence of DU muntions' safety. "Independent investigations by the World Health Organization, European Commission, European Parliament, United Nations Environment Programme, United Kingdom Royal Society, and the Health Council of the Netherlands all discounted any association between depleted uranium and leukemia or other medical problems."[44] In Italy, controversy over the health risks associated with the use of DU continues, with a Senate investigation committee due to release its report into 'Balkan Syndrome' by the end of 2007.[45]

Infectious diseases

Along with possible confounding problems caused by exposure to more than one of the substances listed above, comorbidities with infectious diseases have also not been ruled out.[46] Suspected diseases include leishmaniasis, from sandfly bites, and fungal mycoplasma parasites.

There are some who believe that Gulf War Syndrome is the result of a contagious bacteria. There are anecdotal reports of improvement in some victims when treated with antibiotics.[47]

Further effects of Gulf War Syndrome include a decrease in the quality of vision and hair loss.

Stress

Few would disagree that war is a stressful experience or that all wars carry psychological consequences. Indeed from as far back as the American Civil War there have been reports of the impact of stress on soldier’s emotional wellbeing in the form of Soldier’s Heart. Many psychiatric conditions, including depression and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) can present with physical as well as psychological symptoms.[48] So could Gulf War Syndrome be a physical manifestation of a psychiatric illness?

We know that veterans who were diagnosed with PTSD following World War II, the wars in Vietnam and Lebanon, and the more recent Iraq war all reported poorer self-rated health, and more physical symptoms, independent of their physical injuries.[49] What’s more, post-traumatic stress symptomology has been associated with increased symptom reporting among Persian Gulf war veterans too.[50] Such symptoms in the Gulf war veterans included memory loss, fatigued, confusion, gastrointestinal distress, muscle or joint pain and skin or mucous membrane lesions – all of them possible GWS symptoms as well.

Robert Haley, who first wrote about Gulf War Syndrome and is a critique of the “Stress Theory” of GWS has argued that the way in which we measure PTSD has resulted in a large number of false positives,[51] and goes on to state that the true rate of PTSD in Gulf veterans in negligible.[52]

What does the data show? The rates of PTSD in US and UK do vary considerably (from 2%-25%) but in both self-report and questionnaire based studies it was observed that Gulf war veterans were significantly more likely to report symptoms of PTSD.[53] Overall, what is clear is that the true rates of PTSD, measured by interview and not questionnaire, are indeed elevated. A British study compared disabled and non disabled Gulf veterans, and found that the rates more than doubled in the disabled veterans.[54] And that kind of finding has been repeated several times.

But does that mean that GWS really is a manifestation of PTSD? No. In the same study the rate of PTSD was indeed increased in the sick gulf veterans, but the increase was from 1% to 3%. So 97% of this group do not have PTSD. And whilst twice as many veterans in the disabled group had a formal psychiatric disorder, the remaining 75% did not.[55] Similarly, an American study also reported a link between serving in the Gulf, PTSD, depression and health problems. But again concede that this is unlikely to be the sole cause of Gulf war symptoms.

So PTSD is not the sole explanation of GWS. However, does this mean that stress plays no role in the aetiology of GWS? Perhaps not. The stress and stressors of the early phases of the Gulf war were very real to those preparing to enter Theatre.[56] Not only were the usual pre-combat stressors such as family adjustment and the uncertainty of tour length present, but the very real threat of chemical and biological weapons induced extreme fear in those deployed.[57] Back in 1991 the threat of chemical and biological weapons was real, genuine and serious – this bears no relation to the more recent WMD saga. It is possible that this prolonged stated of anxiety may have led to increased sensitivity to physical symptoms. After all, soldiers were intentionally made aware of the signs and symptoms of chemical and biological weapons and how to respond to them. Perhaps they became chronically sensitised. We do know that pre-combat stressors and stress symptoms were effective predictors of physical health post-deployment.[58]

So there is little doubt that service in the Gulf war, perhaps like service in any war, is indeed associated with an increased risk of longer term psychological problems, and that these do overlap with the symptoms of GWS, but that they are insufficient to explain it. And finally, we should not under estimate the impact of spending up to six months in the build up to the war (“Desert Shield”) living under the very real threat of chemical and biological weapons.

Controversy

There has been considerable controversy over whether or not Gulf War syndrome is a physical medical condition related to sufferers' Gulf War service (or relation to a Gulf War veteran). The following graphs illustrate the state of the controversy in 1998. Since then, as shown by the statistics above, the extent of the problem has become more pronounced.

|

|

Evidence for

United States Veterans Affairs Secretary Anthony Principi's panel found that pre-2005 studies suggested the veterans' illnesses are neurological and apparently are linked to exposure to neurotoxins, such as the nerve gas sarin, the anti-nerve gas drug pyridostigmine bromide, and pesticides that affect the nervous system.

"Research studies conducted since the war have consistently indicated that psychiatric illness, combat experience or other deployment-related stressors do not explain Gulf War veterans illnesses in the large majority of ill veterans," the review committee said.

In November, 2004, the anonymously-funded British inquiry headed by Lord Lloyd[61] concluded, for the first time, that thousands of UK and US Gulf War veterans were made ill by their service. The report claimed that Gulf veterans were twice as likely to suffer from ill health than if they had been deployed elsewhere, and that the illnesses suffered were the result of a combination of causes. These included multiple injections of vaccines, the use of organophosphate pesticides to spray tents, low level exposure to nerve gas, and the inhalation of depleted uranium dust.[62] The report was the first to suggest a direct link between military service in the Persian Gulf and illnesses suffered by veterans of that war and directly contradicts other theories which have suggested GWI is not a physical illness, but a response to the stresses of war.

Increases in the rate of birth defects for children born to Gulf War veterans have been reported. A 2001 survey of 15,000 U.S. Gulf War combat veterans and 15,000 control veterans found that the Gulf War veterans were 1.8 (fathers) to 2.8 (mothers) times as likely to report having children with birth defects.[63]

Although not identifying Gulf War syndrome by name, in June of 2003 the High Court of England and Wales upheld a claim by Shaun Rusling that the depression, eczema, fatigue, nausea and breathing problems that he experienced after returning from the Gulf War were attributed to his military service.

A 2004 British study comparing 24,000 Gulf War veterans to a control group of 18,000 men found that those who had taken part in the Gulf war have lower fertility and are 40 to 50% more likely to be unable to start a pregnancy. Among Gulf war soldiers, failure to conceive was 2.5% vs. 1.7% in the control group, and the rate of miscarriage was 3.4% vs. 2.3%. These differences are small but statistically significant.[64]

In January 2006, a study led by Melvin Blanchard and published by the Journal of Epidemiology, part of the "National Health Survey of Gulf War-Era Veterans and Their Families", stated that veterans deployed in the Persian Gulf War had nearly twice the prevalence of chronic multisymptom illness (CMI), a cluster of symptoms similar to a set of conditions often called Gulf War Syndrome.[65]

Evidence against

Similar syndromes have been seen as an after effect of other conflicts — for example, 'shell shock' after World War I, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after the Vietnam War. A review of the medical records of 15,000 U.S. Civil War soldiers showed that "those who lost at least 5% of their company had a 51% increased risk of later development of cardiac, gastrointestinal, or nervous disease."[66]

A November 1996 article in the New England Journal of Medicine found no difference in death rates, hospitalization rates or self-reported symptoms between Persian Gulf vets and non-Persian Gulf vets. This article was a compilation of dozens of individual studies involving tens of thousands of veterans. The studies did find a statistically significant elevation in the number of traffic accidents suffered by Persian Gulf vets vs. non-Persian Gulf vets.

An April, 1998 article in Emerging Infectious Diseases found no increased rate of hospitalization and better health overall for veterans of the Persian Gulf War vs. Veterans who stayed home. James D. Knoke and Gregory C. Gray, Naval Health Research Center, San Diego, California, USA, Emerging Infectious Diseases 1998 Oct-Dec;4(4):707-9, Hospitalizations for unexplained illnesses among U.S. veterans of the Persian Gulf War.[67]

Additionally, some reported symptoms cannot be verified or connected to Gulf War service. Pfc. Brian Martin, a Gulf War veteran who has appeared on multiple talk shows and given interviews to many newspapers and magazines about Gulf War syndrome, reported developing lupus erythematosus, which news articles claim had been verified by federal medical exams, despite the Department of Veterans Affairs's denial of having had any patients with it.

The US Institute of Medicine, released their conclusions in a September 2006 report further casting doubts on the validity of Gulf War Syndrome, writing that although roughly 30% of service men and women who served either have suffered or still suffer from symptoms,[68] no single cluster of symptoms that constitute a syndrome unique to Gulf War veterans has been identified.[69]

While an increase in birth defects has also been attributed to Gulf War Syndrome, a study on members of the Mississippi National Guard deployed to the Persian Gulf, conducted in 1996 found that of a total of 55 births, five children were born with birth defects. The study concluded that “The rate of birth defects of all types in children born to this group of veterans is similar to that expected for the general population.”[70] In another study of 75,000 births conducted by the New England Journal of Medicine, 7.45% of the Gulf War veteran children were born with birth defects, compared to 7.59% for children of veterans not deployed in the Gulf[71]

New research from the United Kingdom, published in the medical journal the Lancet comparing the health of thousands of service personnel who served in Iraq with the health of thousands who did not, has shown no evidence of any rise in multi symptom conditions associated with Gulf War Syndrome. This casts doubt on the role of certain exposures, such as the anthrax vaccine itself, depleted uranium, pesticides and post traumatic stress, in the aetiology of Gulf War Illnesses, since such exposures were common to both campaigns for the UK forces.[72] After 10 years of research worldwide, overseen by the veterans' lawyers and funded by the UK's Legal Services Commission, no evidence was found which establishes any specific cause for the range of the health problems of over 2000 British troops who were seeking disability pensions for Gulf War Syndrome.[73]

Iraq War

Many U.S. veterans of the 2003 Iraq War have reported a range of serious health issues, including tumors, daily blood in urine and stool, sexual dysfunction, migraines, frequent muscle spasms, and other symptoms similar to the debilitating symptoms of "Gulf War Syndrome" reported by many veterans of the 1991 Gulf War, which some believe is related to the continued United States' use of radioactive depleted uranium.[74]

In Popular Culture

- In the video game Metal Gear Solid, it is mentioned that Gulf War Syndrome is a side effect of genetic engineering conducted by the military.[75]

- In the video game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, Gulf War Syndrome is mentioned in Ammu-Nation commercial on radio.

- Gulf War Syndrome appears on a t-shirt in an episode of The Simpsons entitled "Brother's Little Helper"

- Gulf War Syndrome is the topic of an episode in the popular TV show House M.D.

References

- ^ First Gulf War still claims lives. Seattle Post-Intelligencer. January 16, 2006

- ^ Annals of Internal Medicine. Gulf War Veterans' Health: Medical Evaluation of a U.S. Cohort. June 7, 2005

- ^ (Associated Press, August 12, 2006, free archived copy at: http://www.commondreams.org/headlines06/0812-06.htm Retrieved June 7, 2007)

- ^ Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses December 12-13, 2005 Committee Meeting Minutes (page 78)

- ^ Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses December 12-13, 2005 Committee Meeting Minutes (page 68)

- ^ Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses December 12-13, 2005 Committee Meeting Minutes (page 70)

- ^ Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses December 12-13, 2005 Committee Meeting Minutes (page 71)

- ^ [1]

- ^ Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses December 12-13, 2005 Committee Meeting Minutes

- ^ [2]

- ^ Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses December 12-13, 2005 Committee Meeting Minutes (pages 148, 154, 156)

- ^ Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses December 12-13, 2005 Committee Meeting Minutes (page 73.)

- ^ [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ Antibodies to Squalene in Recipients of Anthrax Vaccine Experimental and Molecular Pathology 73, 19–27, 2002

- ^ [5]

- ^ [6]

- ^ [7]

- ^ http://www.fda.gov/cber/rules/bvactoxanth.pdf

- ^ http://www.fda.gov/cber/rules/bvactox.pdf

- ^ http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2003/NEW01001.html

- ^ [8]

- ^ [9]

- ^ [10]

- ^ [11] [12]

- ^ [13]

- ^ [14]

- ^ [15]

- ^ [16]

- ^ [17]

- ^ [18]

- ^ [19]

- ^ [20],

- ^ [21]

- ^ [22]

- ^ [23]

- ^ Henryk Bema, Firyal Bou-Rabeeb. Environmental and health consequences of depleted uranium use in the 1991 Gulf War

- ^ Bernard D. Rostker. Depleted Uranium, A Case Study of Good and Evil. RAND Corporation

- ^ Hodge S, Ejnik J, Squibb K, McDiarmid M, Morris E, Landauer M, McClain D (2001). "Detection of depleted uranium in biological samples from Gulf War veterans". Mil Med. 166 (12 Suppl): 69–70. PMID 11778443.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gwiazda R, Squibb K, McDiarmid M, Smith D (2004). "Detection of depleted uranium in urine of veterans from the 1991 Gulf War". Health Phys. 86 (1): 12–8. PMID 14695004.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.cerrie.org/committee_papers/INFO_9-H.pdf

- ^ Gulf soldier wins pension fight, BBC, February 3, 2004

- ^ [24] [25]

- ^ [26]

- ^ Anes Alic (October 29, 2007). "Depleted uranium, depleted health concerns". ISN Security Watch.

- ^ [27]

- ^ [28] [29]

- ^ [30] [31]

- ^ [32] [33] [34] [35] [36].

- ^ [37].

- ^ [38]

- ^ [39]

- ^ [40] [41] [42]

- ^ [43]

- ^ [44]

- ^ [45]

- ^ [46]

- ^ [47]

- ^ "Hospitalizations for Unexplained Illnesses among U.S. Veterans of the Persian Gulf War"

- ^ "Hospitalizations for Unexplained Illnesses among U.S. Veterans of the Persian Gulf War"

- ^ [48]

- ^ [49][50]

- ^ Kang H, Magee C, Mahan C, Lee K, Murphy F, Jackson L, Matanoski G (2001). "Pregnancy outcomes among U.S. Gulf War veterans: a population-based survey of 30,000 veterans". Ann Epidemiol. 11 (7): 504–11. PMID 11557183.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [51]

- ^ [52]

- ^ [53]

- ^ [54]

- ^ [55]

- ^ [56]

- ^ Committee to Review the Health Consequences of Services During the Persian War, Medical Follow-up Agency, Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 1996

- ^ Cowan, D. N., R. F. DeFraites, G.C. Gray, M.B. Goldenbaum, and S.M. Wishik, “The Risk of Birth Defects Among Children of Persian Gulf War Veterans,” New England Journal of Medicine 336 23, 1997

- ^ Is there an Iraq war syndrome? Comparison of the health of UK service personnel after the Gulf and Iraq wars. The Lancet, May 16, 2006

- ^ Gulf war syndrome: the legal case collapses

- ^ [57]

- ^ [58]

External links

- American Gulf War Veterans Association

- National Gulf War Resource Center

- Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses

- Uranium Medical Research Centre, founded in 1997 by Dr. Asaf Durakovic, M.D., formerly Chief of Professional Clinical Services in the U.S. Army's 531st Medical Detachment during the Desert Shield phase of the 1991 Gulf War and head of the Veteran's Administration Nuclear

- Post Conflict Assessment Iraq by the United Nations Environment Programme (PDF.)

See also

- Nerve agents

- Khamisiyah the city in Iraq where a chemical weapons storage facility was located and which was bombed during the First Gulf War.

- Beyond Treason an 89-minute 2005 documentary that covers the Gulf War syndrome.

- Siegwart Horst Günther