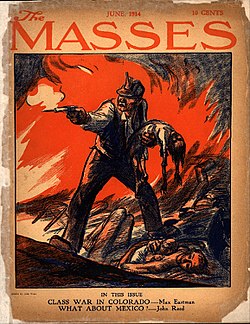

The Masses

The Masses was a graphically innovative magazine of socialist politics published monthly in the U.S. from 1911 to 1917, when government suppression shut it down. It was succeeded by The Liberator and then later The New Masses. It published reportage, fiction, poetry and art by the leading radicals of the time such as Max Eastman, John Reed and Floyd Dell.

History

Piet Vlag, an eccentric socialist immigrant from the Netherlands, founded the magazine in 1911. Vlag’s dream of a co-operatively operated magazine never worked well, and after just a few issues he left for Florida. His vision of an illustrated socialist monthly had, however, attracted a circle of young activists in Greenwich Village to The Masses that included visual artists from the Ashcan school like John French Sloan. These Greenwich Village artists and writers asked one of their own, Max Eastman (who was then studying for a doctorate under John Dewey at Columbia), to edit their magazine. John Sloan, Art Young, Louis Untermeyer, and Inez Haynes Gillmore (among others) mailed a terse letter to Eastman in August 1912: “You are elected editor of The Masses. No pay.”[1]

The Masses was to some extent defined by its association with New York’s artistic culture. “The birth of The Masses,” Eastman later wrote, “coincided with the birth of ‘Greenwich Village’ as a self-conscious entity, an American Bohemia or gipsy-minded Latin Quarter, but its relations with that entity were not simple.”[2] The Masses was very much embedded in a specific metropolitan milieu, unlike some other competing socialist periodicals (such as the Appeal to Reason, a populist-inflected 500,000-circulation weekly produced out of Girard, Kansas).

The magazine carved out a unique position for itself within American left print culture. It was more open to Progressive Era reforms, like women's suffrage, than Emma Goldman's anarchist Mother Earth. At the same time it fiercely criticized more mainstream leftist publications like The New Republic for insufficient radicalism.[3]

World War I continually exercised The Masses’ political imagination. Its editors believed the cause of the conflict was transparently clear: imperialist international finance capital. Grotesque caricatures of Europe’s wealthy bankers directing workingmen’s guns populated the magazine’s pages. Even before it began, throughout the various scares of 1912 and 1913, the paper consistently railed against militarism.

After Eastman assumed leadership, and especially after August 1914, the magazine’s denouncements of the war were frequent and fierce. In the September 1914 edition of his column, “Knowledge and Revolution,” Eastman predicted: “Probably no one will actually be the victor in this gambler’s war—for we may as well call it a gambler’s war. Only so can we indicate its underlying commercial causes, its futility, and yet also the tall spirit in which it is carried off.”[4]

Throughout 1916 and early 1917, in a series of ever more desperate editorials and illustrations, Eastman, Reed, and the others urged against American intervention in the war. Worried about newly-enacted sedition laws like the Espionage Act of 1917, once war was declared in April, the paper avoided direct attacks on American participation in the war.

More indirect critiques of patriotism, and especially of the draft, were enough to get the magazine charged under the stringent anti-sedition laws. The United States Postal Service, under Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson, first denied the magazine second-class mailing privileges. News dealers refused to sell the magazine.[5] In November 1917, the editors of The Masses were indicted on charges they had obstructed enlistment.[6] Although a split jury acquitted Eastman and his cohorts, the dramatically higher postal rates were enough to kill the paper on their own.

After The Masses died, Eastman and other writers were unwilling to let its spirit go with it. In March 1918, their new monthly adopted the name of William Lloyd Garrison’s famed The Liberator.

The Masses continued to serve as an example for radicals long after it was suppressed. “The only magazine I know which bears a certain resemblance to (Dwight Macdonald's magazine) Politics and fulfilled a similar function thirty years earlier,” Hannah Arendt claimed in 1968, was “the old Masses (1911-1917).”[7]

Politics

The Labor Struggle

The magazine reported on most of the major labor struggles of its day: from the the Mine War in West Virginia to the Paterson Silk Strike of 1913 and the Ludlow massacre. It strongly sympathized with Big Bill Haywood and his IWW, the political campaigns of Eugene V. Debs, and a variety of other socialist and anarchist figures. The Masses also indignantly followed the aftermath of the Los Angeles Times bombing.

Women's Rights and Sexual Equality

The magazine vigorously argued for birth control (supporting activists like Margaret Sanger) and women's suffrage. Several of its Greenwich Village contributors, like Reed and Dell, practiced free love in their spare time and promoted it (sometimes in veiled terms) in their pieces. Support for these social reforms was sometimes controversial within Marxist circles at the time; some argued that they were distractions from a more proper political goal, class revolution. Emma Goldman once tutted: “It is rather disappointing to find THE MASSES devoting an entire edition to ‘Votes for Women.’ Perhaps Mother Earth alone has any faith in women […] that women are capable and are ready to fight for freedom and revolution.”[8]

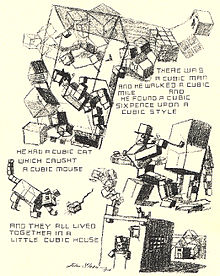

Illustrations

Although the magazine's birth coincided with the explosion of modernism, and its contributor Arthur B. Davies was an organizer of the Armory Show, The Masses published for the most part realist artwork that would later be classified in the Ashcan school. Many illustrations were appended with captions, a policy that irritated John French Sloan so much he left the magazine's staff.

Literature & Criticism

American realism was a vital, pioneering current in the writing of the time, and several leading lights were willing to contribute work to the magazine without pay. The name most associated with the magazine is Sherwood Anderson. Anderson was “discovered” by The Masses’ fiction editor, Floyd Dell, and his pieces there formed the foundation for his Winesburg, Ohio stories. In the November 1916 Masses, Dell described his surprise years before while reading Anderson’s unsolicited manuscript: “there Sherwood Anderson was writing like—I had no other phrase to express it—like a great novelist.”[9] Anderson would later be cited by the Partisan Review circle as one of the first homegrown American talents.

The magazine's criticism, edited by Floyd Dell, was cheekily titled (at least for a time) “Books that Are Interesting.” Dell’s perceptive reviews gave accolades to many of the most notable books of the time: An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution, Spoon River Anthology, Theodore Dreiser’s novels, Carl Jung’s Psychology of the Unconscious, G.K. Chesterton’s works, Jack London’s memoirs, and many other prominent creations.

Notable contributors

Sherwood Anderson

George Bellows

Arthur B. Davies

Floyd Dell

Max Eastman

Jack London

Amy Lowell

Inez Milholland

John Reed

John French Sloan

Upton Sinclair

Louis Untermeyer

Art Young

See also

Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten

Further reading

- O'Neill, William. Echoes of Revolt: The Masses, 1911-1917. Ivan R. Dee, Publisher. ISBN 0-929587-15-4.

- Zurier, Rebecca. Art for The Masses: A Radical Magazine and Its Graphics, 1911-1917. Temple University Press. ISBN 0-87722-670-9.

External links

Archives

- Cover Illustrations Collection at Michigan State University

- "The Radical Impulse" from the Library of Congress Exhibition "Life of the People"

- Political Cartoons from the Masses. Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved on March 11, 2006.

- Max Eastman archive

- John Reed archive

Articles

- "The Crayon Was Mightier Than the Sword" by David Oshinsky in the New York Times (September 4, 1988).

- The Masses article on Spartacus online encyclopedia. Retrieved on March 11, 2006.

References

- ^ Max Eastman, Enjoyment of Living, New York: Harper & Brothers, 1948. 394.

- ^ Enjoyment of Living, 418.

- ^ The Masses, April 1916, 12.

- ^ The Masses, September 1914, 4.

- ^ "News Dealers Won't Sell the Masses." The New York Times. November 7, 1917.

- ^ "Indicts the Masses and 7 of Its Staff." The New York Times. November 20, 1917.

- ^ Hannah Arendt, “He’s All Dwight,” The New York Review of Books, August 1, 1968.

- ^ Quoted in The Masses, January 1916, 20.

- ^ The Masses, November 1916, 17.