Chirp

A chirp is a signal in which the frequency increases ('up-chirp') or decreases ('down-chirp') with time. It is commonly used in sonar and radar, but has other applications, such as in spread spectrum communications. In spread spectrum usage, SAW devices such as RACs are often used to generate and demodulate the chirped signals. In optics, ultrashort laser pulses also exhibit chirp due to the dispersion of the materials they propagate through.

Types of chirp

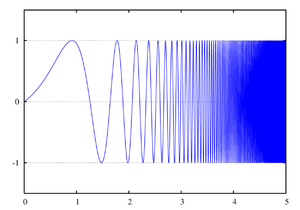

Linear chirp

In a linear chirp, the instantaneous frequency f(t ) varies linearly with time:

where f0 is the starting frequency (at time t = 0), and k is the rate of frequency increase or chirp rate. The corresponding time-domain function for a sinusoidal linear chirp is:

Exponential chirp

In a geometric chirp, also called an exponential chirp, the frequency of the signal varies with a geometric relationship over time. In other words, if two points in the waveform are chosen, t1 and t2, and the time interval between them t2 − t1 is kept constant, the frequency ratio f(t2)/f(t1) will also be constant.

In an exponential chirp, the frequency of the signal varies exponentially as a function of time:

where f0 is the starting frequency (at t = 0), and k is the rate of exponential increase in frequency. Unlike the linear chirp, which has a constant chirp rate, an exponential chirp has an exponentially increasing chirp rate. The corresponding time-domain function for a sinusoidal exponential chirp is:

Although somewhat harder to generate, a geometric chirp does not suffer from reduction in correlation gain if the echo is Doppler-shifted by a moving target. This is because the Doppler shift actually scales the frequencies of a wave by a multiplier (shown below as the constant c).

From the equations above, it can be seen that this actually changes the rate of frequency increase of a linear chirp (kt multiplied by a constant) so that the correlation of the original function with the reflected function is low.

Because of the geometric relationship, the Doppler shifted geometric chirp will effectively start at a different frequency (f0 multiplied by a constant), but follow the same pattern of exponential frequency increase, so the end of the original wave, for instance, will still overlap perfectly with the beginning of the reflected wave, and the magnitude of the correlation will be high for that section of the wave.

A chirp signal can be generated with analog circuitry via a VCO, and a linearly or exponentially ramping control voltage. It can also be generated digitally by a DSP and DAC, perhaps by varying the phase angle coefficient in the sinusoid generating function.

Uses and occurences

Chirp modulation

Chirp modulation, or linear frequency modulation for digital communication was patented by Sidney Darlington in 1954 with significant later work performed by Winkler in 1962. This type of modulation employs sinusoidal waveforms whose instantaneous frequency increases or decreases linearly over time. These waveforms are commonly referred to as linear chirps or simply chirps.

Hence the rate at which their frequency changes is called the chirp rate. In binary chirp modulation, binary data is transmitted by mapping the bits into chirps of opposite chirp rates. For instance, over one bit period "1" is assigned a chirp with positive rate a and "0" a chirp with negative rate −a. Chirps have been heavily used in radar applications and as a result advanced sources for transmission and matched filters for reception of linear chirps are available[1].

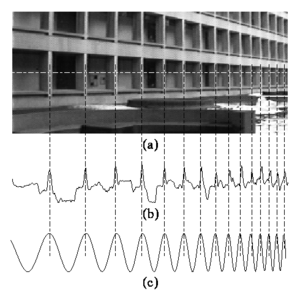

Chirplet transform

Another kind of chirp is the projective chirp, of the form , having the three parameters a (scale), b (translation), and c (chirpiness). The projective chirp is ideally suited to image processing, and forms the basis for the projective chirplet transform.

Key chirp

A change in frequency of Morse code from the desired frequency, due to poor stability in the RF Oscillator is known as chirp[1], and in the RST code is given an appended letter 'C'.

See also

- Chirplet transform — A signal representation based on a family of localized chirp functions, each member of which can usually be expressed as parameterized transformations of each other.

- Pulse compression - A signal processing technique designed to maximize the sensitivity and resolution of radar systems by modifying transmitted pulses to improve their auto-correlation properties. One way of accomplishing this is to chirp the RADAR signal (also known as Chirp Radar).

- Chirp Spread Spectrum - A part of the wireless telecommunications standard IEEE 802.15.4a CSS (see Chirp Spread Spectrum (CSS) PHY Presentation for IEEE P802.15.4a).

- continuous-wave radar

- SHARAD

- chirped pulse amplification

- chirped mirror

- dispersion (optics)

References

- ^ The Beginner's Handbook of Amateur Radio By Clay Laster

![{\displaystyle g=f[(a\cdot x+b)/(c\cdot x+1)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/676817f0a92446d449867b56cd74f5ade5273bfa)