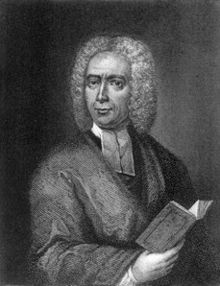

Isaac Watts

Isaac Watts (July 17, 1674 – November 25, 1748) is recognised as the "Father of English Hymnody", as he was the first prolific and popular English hymnwriter, credited with some 750 hymns. Many of his hymns remain in active use today and have been translated into many languages.

Life

Born in Southampton, Watts was brought up in the home of a committed Nonconformist — his father, also Isaac Watts, had been incarcerated twice for his controversial views. At King Edward VI School (where one of the houses is now named "Watts" in his honour), he learned Latin, Greek and Hebrew and displayed a propensity for rhyme at home, driving his parents to the point of distraction on many occasions with his verse. Once, he had to explain how he came to have his eyes open during prayers.

- "A little mouse for want of stairs

- ran up a rope to say its prayers."

Receiving corporal punishment for this, he cried

- "O father, do some pity take

- And I will no more verses make."

Watts, unable to go to either Oxford or Cambridge due to his Non-conformity, went to the Dissenting Academy at Stoke Newington in 1690.

His education led him to the pastorate of a large Independent Chapel in London, and he also found himself in the position of helping trainee preachers, despite poor health. Taking work as a private tutor, he lived with the non-conformist Hartopp family at Fleetwood House, Abney Park in Stoke Newington, and later in the household of Sir Thomas Abney and Lady Mary Abney at Theobalds, Cheshunt, in Hertfordshire, and at their second residence, Abney House, Stoke Newington. Though a non-conformist, Sir Thomas practised occasional conformity to the Church of England as necessitated by his being Lord Mayor of London 1700–01. Likewise Isaac Watts held religious opinions that were more non-denominational or ecumenical than was at that time common for a non-conformist; having a greater interest in promoting education and scholarship, than preaching for any particular ministry.

On the death of Sir Thomas Abney, Watts moved permanently with widow, Lady Mary Abney, and her remaining daughter, to their second home, Abney House, at Abney Park in Stoke Newington - a property that Mary had inherited from her brother along with title to the Manor itself. The beautiful grounds at Abney Park, which became Watts' permanent home from 1736 to 1748, led down to an island heronry in the Hackney Brook where Watts sought inspiration for the many books and hymns written during these two decades. He died there in Stoke Newington and was buried in Bunhill Fields, having left behind him a massive legacy, not only of hymns, but also of treatises, educational works, essays and the like. His work was influential amongst independents and early religious revivalists in his circle, amongst whom was Philip Doddridge who dedicated his best known work to Watts. On his death, Isaac Watts' papers were given to Yale University; an institution with which he was connected due to its being founded predominantly by fellow Independents (Congregationalists).

Watts and hymnody

Sacred music scholar Stephen Marini (2003) describes the ways in which Watts contributed to English hymnody.[1] Notably, Watts led the way in the inclusion in worship of "original songs of Christian experience"; that is, new poetry. The older tradition limited itself to the poetry of the Bible, notably the Psalms. This stemmed from the teachings of the 16th century Reformation leader John Calvin, who initiated the practice of creating verse translations of the Psalms in the vernacular for congregational singing.[2] Watts' introduction of extra-Biblical poetry opened up a new era of Protestant hymnody as other poets followed in his path.[3]

Watts also introduced a new way of rendering the Psalms in verse for church services. The Psalms were originally written in Biblical Hebrew within the religion of Judaism. Later, they were adopted into Christianity as part of what Christians call the Old Testament. Watts proposed that the metrical translations of the Psalms as sung by Protestant Christians should give them a specifically Christian perspective:

- "While he granted that David [to whom authorship of the Psalms is traditionally ascribed] was unquestionably a chosen instrument of God, Watts claimed that his religious understanding could not have fully apprehended the truths later revealed through Jesus Christ. The Psalms should therefore "renovated" as if David had been a Christian, or as Watts put it in the title of his 1719 metrical psalter, they should be "imitated in the language of the New Testament."[1]

Marini discerns two particular trends in Watts' verses, which he calls "emotional subjectivity" and "doctrinal objectivity". By the former he means that "Watts' voice broke down the distance between poet and singer and invested the text with personal spirituality." As an example of this he cites "When I Survey the Wondrous Cross". By "doctrinal objectivity" Marini means that Watts verse achieved an "axiomatic quality" that "presented Christian doctrinal content with the explicit confidence that befits affirmations of faith." As examples Marini cites the hymns "Joy to the World" as well as "From All That Dwell Below the Skies":[4]

- From all that dwell below the skies

- Let the Creator's praise arise;

- Let the Redeemer's name be sung

- Through every land, by every tongue.

Significant Cultural or Contemporary Impacts

- One of his best known poems was an exhortation "Against Idleness And Mischief" in Divine Songs for Children, a poem which was famously parodied by Lewis Carroll in his book Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, in the poem "How Doth the Little Crocodile," which is now better known than the original.

- In the 1884 comic opera called Princess Ida, there is a punning reference to Watts in Act I. At Princess Ida's women's university no males of any kind are allowed, and the Princess's father, King Gama, relates that "She'll scarcely suffer Dr. Watts' 'hymns'".

- Isaac Watts is commemorated as a hymnwriter in the Calendar of Saints of the Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod and Evangelical Lutheran Church in America on November 25

Other works

Besides being a famous hymn-writer, Isaac Watts was also a renowned theologian and logician, writing many books and essays on these subjects. Watts was the author of a text book on logic which was particularly popular; its full title was, Logic, or The Right Use of Reason in the Enquiry After Truth With a Variety of Rules to Guard Against Error in the Affairs of Religion and Human Life, as well as in the Sciences. This was first published in 1724, and its popularity ensured that it went through twenty editions.

In this text book Watts divided logic into four branches: perception, judgement, reasoning, and method, which he treated in this order. In the first section Watts discusses the origin and nature of ideas, and the relationship between words and ideas, and it is easy to detect the influence of John Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding in this section. He provides chapters on how to arrive at clear and distinct ideas, the definition of names, the definition of things, and the division of ideas. The next section is concerned with judgements and propositions, and the division of these. Here, Watts largely follows the scholastic tradition and divides propositions into universal affirmative, universal negative, particular affirmative and particular negative, and he proceeds to discuss the nature of these kinds of propositions, showing how to convert one to the other. In addition he examines errors in judgement and prejudices that can pervert our judgements, before setting down directions to avoid these sources of error. In the third section, Watts discusses reasoning conceived as argumentation, with particular emphasis on the theory of syllogism, which was a centrally important part of logic at the time. The final section discusses method, which he defines as 'the disposition of a variety of thoughts on any subject in such order as may best serve to find out unknown truths, to explain and confirm truths that are known, or to fix them in the memory.'[5]

Isaac Watts' Logic became the standard text on logic at Oxford, Cambridge, Harvard and Yale; being used at Oxford University for well over 100 years. Charles Sanders Peirce, one of the greatest nineteenth century logicians, wrote favourably of Watts' Logic. When preparing his own text book on Logic entitled A Critick of Arguments: How to Reason (also known as the Grand Logic), Peirce wrote, 'I shall suppose the reader to be acquainted with what is contained in Dr Watts' Logick, a book very cheap and easily procured, and far superior to the treatises now used in colleges, being the production of a man distinguished for good sense.' [6] The Logic was followed in 1741 by a supplement, The Improvement of the Mind, which itself went through numerous editions and later inspired Michael Faraday.

Memorials

The earliest surviving built memorial to Isaac Watts is at Westminster Abbey; this was completed shortly after his death. His much-visited chest tomb, in its photogenic setting at Bunhill Fields, dates from 1808, replacing the original that had been paid for and erected by Lady Mary Abney and the Hartopp family. In addition a stone bust of Watts can be seen in the non-conformist library Dr Williams's Library in central London. The earliest public statue stands at Abney Park, where he lived and died before it became a cemetery and arboretum; a later, rather similar statue, was funded by public subscription for a new Victorian public park in the city of his birth, Southampton. In the mid nineteenth century a Congregational Hall, the Dr Watts Memorial Hall, was also built in Southampton, though after the Second World War it was lost to redevelopment. Now standing on this site is the Isaac Watts Memorial United Reformed Church.

One of the earliest built memorials may also now be lost: a bust to Watts that was commissioned on his death for the London chapel with which he was associated. The chapel was demolished in the late eighteenth century; remaining parts of the memorial were rescued at the last minute by a wealthy landowner for installation in his chapel near Liverpool. It is unclear whether it still survives.

The stone statue in front of the Abney Park Chapel at Dr Watts' Walk, Abney Park Cemetery, was erected in 1845 by public subscription. It was designed by the leading British sculptor, Edward Hodges Baily RA FRS. A scheme for a commemorative statue on this spot had first been promoted in the late 1830s by George Collison, who in 1840 published an engraving as the frontispiece of his book about cemetery design in Europe and America; and at Abney Park Cemetery in particular. This first cenotaph proposal was never commissioned, and Baily's later design was adopted in 1845.

Works

Books

- The Improvement of the Mind Vol 1 Vol 2 at The Internet Archive

- Logic, or The Right Use of Reason in the Enquiry After Truth With a Variety of Rules to Guard Against Error in the Affairs of Religion and Human Life, as well as in the Sciences[1]

- A Short View of the Whole Scripture History: With a Continuation of the Jewish Affairs From the Old Testament Till the Time of Christ; and an Account of the Chief Prophesies that Relate to Him[2]

Hymns

Some of Watts' more well-known hymns are:

- Joy to the world! (sung to a tune by Lowell Mason, frequently attributed in error to Handel)

- Come ye that love the Lord (often sung with the chorus [and titled] "We’re marching to Zion")

- Come Holy Spirit, heavenly Dove

- Jesus shall reign where’er the sun

- O God, Our Help in Ages Past

- When I survey the wondrous cross

- Alas! and did my Saviour bleed

- This is the day the Lord has made

Many of his hymns are included in the Methodist hymn book Hymns and Psalms. Many of his texts are also used in the American hymnal The Sacred Harp, using what is known as the shape-note singing technique.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Marini 2003, 76

- ^ Marini 2003, 71

- ^ Marini (2002, 76) lists the following as hymnwriters who can be considered as followers of the tradition established by Watts: Charles Wesley, Edward Perronet, Ann Steele, Samuel Stennet, Augustus Toplady, John Newton, William Cowper, Reginald Heber and (in America) Samuel Davies, Timothy Dwight, John Leland, and Peter Cartwright.

- ^ Reference for this paragraph: Marini 2003, 76. The full text of "From All That Dwell below the Skies can be found at http://www.virtu-software.com/projecthymnbook/song.asp?sid=67 and other Web locations.

- ^ Watts, I (1825 reprint) Logic or the Right Use of Reason in the Inquiry After Truth; with a Variety of Rules to Guard Against Error in the Affairs of Religion and Human Life, as well as in the Sciences Kessinger Books, United States.

- ^ Peirce, C.S. (1933) The Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, vol.II, Paul Weiss and Charles Hartshorne, eds. Cambridge MASS, Harvard University Press

References

- Marini, Stephen A. (2003) Sacred Song in America: Religion, Music, and Public Culture. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

External links

- Works by Isaac Watts at Project Gutenberg

- A Solemn Address to the Great and Ever Blessed God (1802), originally published as A Faithful Inquiry after the Ancient and Original Doctrine of the Trinity (1745)

- The Isaac Watts Fan Club background info and midi files

- Hymns by Isaac Watts

- O God our help in ages past (this is the official school hymn of King Edward VI School, Southampton, Watts' alma mater)

- Monergism.com Isaac Watts Links to works of Isaac Watts