Anterior cruciate ligament

| Anterior cruciate ligament | |

|---|---|

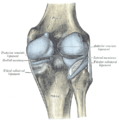

Diagram of the right knee. (Anterior cruciate ligament labeled at center left.) | |

| Details | |

| From | lateral condyle of the femur |

| To | intercondyloid eminence of the tibia |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | ligamentum cruciatum anterius |

| MeSH | D016118 |

| TA98 | A03.6.08.007 |

| TA2 | 1890 |

| FMA | 44614 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL, commonly referred to just as the cruciate ligamentor "lateral Cruciate ligment"") is one of the four major ligaments of the knee. It connects from a posterio-lateral part of the femur to an anterio-medial part of the tibia. These attachments allow it to resist anterior translation of the tibia, in relation to the femur. More specifically, it is attached to the depression in front of the intercondyloid eminence of the tibia, being blended with the anterior extremity of the lateral meniscus. It passes up, backward, and laterally, and is fixed into the medial and back part of the lateral condyle of the femur.

Anterior cruciate ligament injury is the most common knee ligament injury.

Causes of injury

The ACL is the most commonly injured knee ligament [1] and is commonly damaged by athletes. The ACL is often torn during sudden dislocation, torsion, or hyperextension of the knee. Swelling that is usually attributed to bleeding from the tear may cause pressure and some discomfort, and can be severely painful. It is a very common injury in football, hockey, skiing, skating, soccer (and other field sports) and in most cases basketball, due to the enormous amount of pressure, weight, and torque the knee must withstand. Usually the injury occurs when someone tries to rapidly change direction with the leading leg out, twisting the knee; this is usually followed by a loud popping sound. Or sudden high pressure contact, especially side on. Generally if the knee is locked, and the leg is firmly planted, then there is a much greater risk of injury.

The known causes of ACL rupture can be divided into three major classifications:

- environmental

- anatomical

- hormonal [2]

Environmental causes

Sports which include running, jumping, and landing pose the most potential for injury to the athlete. Interestingly, the risk for rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament does not increase in contact sports (as opposed to noncontact sports). According to Maureen Madden, a physical therapist working with many ACL rupture patients, "the most encouraging aspect of the bad news about ACL tears is that 70 (percent) are noncontact injuries." [3]

Anatomical causes

ACL injuries are especially common in female athletes, due to many possible contributing factors. The most prevalent explanation relates to female athletes tending to land more straight-legged than men, removing the quadriceps' muscles shock-absorbing action on the knee. Often the knee on a straight leg can't withstand this and bends sideways.

Hormonal causes

High levels of specific hormones have been associated with an increased risk of ACL rupture. Estrogen is one of these hormones. Some anatomical and hormonal causes (such as high levels of estrogen) may put women at a higher risk for injury.[2]

Women and ACL Tears

Statistics show that females are now more than 8 times as likely to tear their ACL than male athletes. Statistics also show that female athletes have a 25% chance of tearing their ACL a second time after having the reconstruction surgery done. Differences between the sexes in hormones, adolescence, ligament dominance and quadriceps dominance, biomechanics, anatomy, asymmetry, and psychology all may contribute to this anomaly.

Menstrual Cycle and Hormones

Doctors and scientists have done many tests showing that the women’s menstrual cycle may have a lot to do with why their anterior cruciate ligaments are more at risk. [4] According to the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, the largest and most basic difference between men and women is the monthly menstrual cycle. The cycle causes hormone changes and imbalances throughout. Studies show that there were more women that were tearing their ACL while having their menstrual cycle then when they do not. During the menstrual cycle hormone metabolite levels are higher and more imbalanced than when not ovulating. [4] There are also studies that show that women who are on birth control do not have as great of a chance of tearing their ACL because their hormones are more balanced then women who are not on birth control. Although scientists know that a hormonal increase may have something to do with the increase in ACL tears, they still are not sure why.[4]

Adolescents

Young girls aren’t as likely to tear their ACL’s as young women. According to Anna Kessel, when puberty occurs this is changes the risk of women tearing their ACL from 2 times to 4 times more than men. When males hit puberty they gain muscle strength throughout their body where as a woman’s body becomes more flexible. Flexibility is bad when a women does not have the proper amount of strength to keep the joints stable. [5]

Ligament and Quadriceps Dominance

Women’s bodies tend to work in a way that uses the ligaments more than it uses muscles. When ligaments are compensating for muscles, it makes the ligaments weak and more susceptible to damage.[5]Male athletes are more likely to use their hamstrings instead of their ligaments for stability. Instead of using their hamstrings, women tend to use their quadriceps, which compresses the joint and pulls the tibia forward. Doing this can cause damage or stress on the Anterior Cruciate Ligament. The quadriceps are made up of four muscles that help straighten the knee. [5]When an athlete tears an ACL and has reconstruction surgery, the quadriceps are one of the most important muscles to strengthen at therapy.

Biomechanics

A woman’s body is shaped in a way that when they are jumping, pivoting, and landing, their knees are likely to bend inward. Doing so makes the weight unevenly distributed throughout the woman’s body. Scientists are also suggesting that the difference in men’s and women’s femoral notch may be another reason woman tear their ACL more than men. The femoral notch is the space at the bottom of the femur, where the ACL runs. In woman, the femoral notch is narrower then the femoral notch in men. It is suggested that since the woman’s femoral notch is smaller that the femur grinds the ACL and can make it weaker. Another biomechanic that is said to likely cause ligament damage is the quadriceps femoris muscle angle, also known as the “Q-Angle”. This is different in woman’s bodies then men’s bodies in that this angle is bigger in woman’s bodies because of their bigger pelvis. The women’s ACL is also shaped slightly differently than a male’s ACL. The Women’s ACL, according to Jonathan Cluett, M.D. is a little smaller.

Diagnosis

Several diagnostic maneuvers help clinicians diagnose an injured ACL. In the anterior drawer test, the examiner applies an anterior force on the proximal tibia with the knee in 90 degrees of flexion. The Lachman test is similar, but performed with the knee in only about twenty degrees of flexion, while the pivot-shift test adds a valgus (outside-in) force to the knee while it is moved from flexion to extension. Any abnormal motion in these maneuvers suggests a tear.

The diagnosis is usually confirmed by MRI, the availability of which has greatly lessened the number of purely diagnostic arthroscopies performed.

Treatment options

Treatment for an ACL injury can either be nonsurgical or surgical depending on the extent of the injury.

Nonsurgical options may be used if the knee cartilage is undamaged, the knee proves to be stable during typical daily activities, and if the patient has no desire to ever again participate in high-risk activities (activities involving cutting, pivoting, or jumping). If the nonsurgical option is recommended, the doctor may recommend physical therapy, wearing a knee brace, or adapting some typical activies. If physical therapy is recommended it will be used to strengthen the muscles around the knee to compensate for the absence of a healthy ACL. Physical therapy will focus on strengthening muscles such as the hamstring, quadricep, calf, hip, and ankle. This therapy will help to re-establish a full range of motion of the knee. With the use of these nonsurgical options a patient can expect to be back to normal daily activity within one month. Other non-surgical options include prolotherapy, which has been shown by Reeves in a small RCT to reduce translation on KT-1000 arthrometer versus placebo.[6] The future of non-surgical care for ACL laxity (partial ligament tear) is likely bioengineering. Fan has demonstrated that ACL reconstruction is possible using mesenchymal stem cells and a silk scaffold.[7] In addition, commercial applications of this injection based procedure are just becoming available in the US.[8]

Surgical options may be used if the knee gives way during typical daily activities, showing functional instability, or if the patient is unable to refrain from participate in high-risk activies ever again. Reconstructive surgery may also be recommended if there is damage to the meniscus (cartilage). This surgery is completed using arthroscopic techniques. There is also an option for an autograft to be done using a chosen tendon. There however are pros and cons to the surgical treatment, and consideration of possibly complications must be thought through and discussed with your surgeon before proceeding with this form of treatment. If the surgical treatment is chosen there are also rehabilitation requirements. Physical therapy must be completed in three phases after the surgery is completed. With the use of the surgical treatment option, rehabilitation included, one can expect to be returning to their previous and desired level of activity in six to (what up dogs) nine months.[9]

See also

- Knee

- Lateral collateral ligament

- Medial collateral ligament

- Posterior cruciate ligament

- Anterior drawer test

- Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

Additional images

-

Right knee-joint, from the front, showing interior ligaments.

-

Left knee-joint from behind, showing interior ligaments.

-

Head of right tibia seen from above, showing menisci and attachments of ligaments.

-

Capsule of right knee-joint (distended). Posterior aspect.

References

- ^ Widuchowski W, Widuchowski J, Trzaska T (2007). "Articular cartilage defects: study of 25,124 knee arthroscopies". Knee. 14 (3): 177–82. doi:10.1016/j.knee.2007.02.001. PMID 17428666.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Coggin, Amber. ""ACL Study Links Injury to Menstrual Cycle." The Reporter. 2 Feb. 2005. Vanderbilt Medical Center".

- ^ Madden, Maureen. ""Women and ACL Injuries: Taking the Bad News with the Good." The Stone Clinic.".

- ^ a b c ,The American Journal of Sports Medicine.

- ^ a b c Kessel, Anna (October 28, 2008). "Are Women More Prone to Injury?". The Observer. Cite error: The named reference "test2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Reeves KD, Hassanein K. "Randomized prospective double-blind placebo-controlled study of dextrose prolotherapy for knee osteoarthritis with or without ACL laxity". PubMed.

- ^ Fan H, Liu H, Wong EJ, Toh SL, Goh JC. "In vivo study of anterior cruciate ligament regeneration using mesenchymal stem cells and silk scaffold". PubMed.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Mesenchymal stem cell based procedure". Regenerative Sciences.

- ^ Mayo Clinic Staff. "ACL Injury": Treatment Options".

External links

- http://www.cincinnatisportsmed.com/csmref/index.asp?ipath=../csm/patedu/knee/acl.htm

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Reconstruction

- Anatomy photo:17:02-0701 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Major Joints of the Lower Extremity: Knee Joint"

- Anatomy figure: 17:07-08 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Superior view of the tibia."

- Anatomy figure: 17:08-03 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Medial and lateral views of the knee joint and cruciate ligaments."

- Template:EMedicineDictionary

- MedicalMnemonics.com: 2081

- lljoints at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (antkneejointopenflexed)

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair - Series (University of Maryland)

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament, Virtual Health Care Team at the University of Missouri-Columbia

- http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/acl-injury/AC99999/PAGE=AC00006..."ACL Injury" treatment options, surgical/nonsurgical, etc.